The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, highly important for walking, running and impact activities, fuse to form the Achilles tendon, which is the largest and strongest tendon in the body.1 The tendon needs to withstand up to eight times body weight in force when undertaking sporting activities,2 and injuries to the Achilles tendon are common. Incidence and prevalence of Achilles tendon injuries has increased in the past 30 years, thought to be due to a combination of an active, ageing population and increased participation in sport and exercise programs in general.3

Achilles tendon injuries can be divided into acute ruptures and chronic overuse injuries. Both can be debilitating, with significant morbidity for patients; fortunately, both types of injuries respond well to non-operative and operative interventions, and only a small proportion requiring surgical intervention.

Acute rupture

Acute rupture of the Achilles tendon is a common injury, accounting for 20% of all large tendon ruptures. The estimated incidence ranges from 11 to 37 per 100,000 population, with men more than twice as likely to rupture their Achilles tendon than women.4 This injury has a bimodal distribution, with the first peak occurring in people aged 25–40 years who are participating in high-energy sports, and the second peak in people aged >60 years. This second peak in more elderly patients is commonly associated with a low-energy injury, such as getting up from a seated position, after a history of Achilles pain. The risk of rerupture is higher in elderly patients with a degenerative tendon because of the inherent poor quality and diminished vascular supply of the tendon fibres.5 In the younger population, histological studies performed on acute Achilles tendon ruptures have shown clear degenerative changes despite little or no symptoms pre-injury.6

Patients who sustain an acute Achilles tendon rupture often describe a ‘gunshot’ sensation to the back of the leg. In the younger population with sports-associated Achilles tendon ruptures, up to 90% of cases are related to an acceleration–deceleration mechanism.7 Despite the characteristic history and symptoms, it is often a missed injury, with up to 25% of cases misdiagnosed at initial presentation.8

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics (commonly ciprofloxacin) have a known association with Achilles tendinitis and rupture, with a latency period of between two and 60 days. Patients aged >60 years are more likely to develop fluoroquinolone-induced tendinitis.9 Other risk factors include rheumatoid arthritis, gout, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic uraemia and hyperparathyroidism, although these conditions are only responsible for Achilles tendon ruptures in <2% of cases.1

To enable examination of a potential rupture of the Achilles tendon, the patient should be in the prone position or kneeling on a chair so the area can be easily inspected for bruising or other skin changes. The physical examination for detection of an acute Achilles tendon rupture has been described as ‘Simmonds’ triad’:10

- Look at the angle of declination of the foot in comparison to the contralateral side.

- Feel for a palpable gap.

- Move (‘squeeze test’) – this involves a gentle squeeze of the calf with the foot hanging off the edge of the bed. If there is no movement of the foot, the test is positive, suggesting disruption of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Demonstration of a negative Simmonds’ squeeze test (no rupture evident)

The presence of two of the three signs has been shown to be 100% sensitive for an acute Achilles tendon rupture.11

Differential diagnoses that warrant exclusion include ankle fracture, ankle sprain or chronic tendinopathy to the long tendons at the back of the ankle. A careful history to ascertain the mechanism of injury combined with clinical examination can help exclude these injuries. It is important that an avulsion fracture of the calcaneal tuberosity (Figure 2) is not inadvertently diagnosed as an Achilles tendon rupture. These fractures commonly occur in elderly patients with diabetes, patients taking immunosuppressive medication or those with a history of osteopaenia.12 During examination, if palpation of the Achilles tendon yields a bony lump or there is evidence of skin tension, the patient should be placed in a plantarflexed cast and an urgent X-ray of the ankle ordered. This injury is a surgical emergency because of the risk of skin necrosis as the bony fragment causes tension on the overlying skin.

Figure 2. Calcaneal tuberosity fracture

If there is any doubt regarding the diagnosis, ultrasonography of the Achilles tendon is useful to confirm examination findings. It is recommended that clinical findings are communicated to the reporting radiologist via a detailed referral form, specifying whether the concern is an acute or chronic condition, and patients are referred to centres with ultrasonographers and radiologists experienced in musculoskeletal ultrasonography. Careful correlation with clinical symptoms should be made, as chronic changes can be reported as a degenerative or partial tear of the tendon. It has been shown that ultrasonography is more effective than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for dynamically identifying the location of a tear or measuring the gap between the torn tendon edges, and differentiating between a partial and complete rupture.13 Therefore, MRI is not routinely used as a diagnostic tool for an acute rupture in this author’s practice.

Management of acute Achilles tendon ruptures continues to be debated, but there is emerging evidence that supervised non-operative management results in very good outcomes. A randomised controlled trial of 144 patients randomised to operative and non-operative intervention reported no clinically important difference between groups with regard to strength, range of motion or calf circumference two years post-injury.14 The authors also reported a wound complication rate of 15% in the operative group. A Cochrane review reported a higher rerupture rate of 12% with non-operative treatment, compared with 5% in patients who receive surgery, but a complication rate of 30% in patients who receive surgery, compared with 8% in non-operatively treated patients.15

To reduce the risk of functional lengthening (in which the tendon heals in an elongated position causing long-term weakness), patients need to be placed in a plantarflexed cast, backslab or removable orthosis with a heel wedge to force the ankle into plantarflexion as early as possible.5 Common removable orthoses include a controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot (Figure 3). Ideally the patient is placed in a cast or boot in the emergency department setting within hours of the injury occurring. A referral to the local public hospital fracture clinic or orthopaedic surgeon should be made as soon as possible after the injury so appropriate management options can be discussed with the patient. It is recommended that patients with a suspected acute Achilles tendon rupture are seen within seven days of the initial injury.

Figure 3. Controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot

Source: Össur. All rights reserved.

In this author’s practice, patients are routinely treated non-operatively. An orthopaedic surgeon discusses the risk factors for operative and non-operative treatment modalities in detail with the patient, and patients are commenced on a functional rehabilitation program as directed by an Australian Physiotherapy Association–accredited sports physiotherapist or podiatrist employed by the practice. Involvement of an orthopaedic surgeon in non-operative management results in recognition of failure of non-operative measures as well as early discussion about potential surgery in the future if required. Rehabilitation protocols are shared with the patient’s regular allied health practitioner for ongoing management, and they are reviewed by both surgeon and physiotherapist six weeks and 12 weeks post-injury.

It has been shown that a removable orthosis such as a CAM boot results in more favourable outcomes when compared with casting.16 It has also been shown that early weight-bearing and loading of the tendon result in improved clinical outcomes.17 Willets et al have published a detailed accelerated functional rehabilitation protocol for non-operative management of acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon, which is followed by this author’s practice (Table 1).14 This protocol is well tolerated by patients, and the practice collaborates with local allied health practitioners (including physiotherapists and podiatrists) to improve compliance and supervision of non-operative management.

| Table 1. Accelerated functional rehabilitation protocol14 |

| Phase |

Instructions for patients |

Recovery phase

0–2 weeks post-injury |

- Attend public fracture clinic or orthopaedic surgeon

- Wear plaster backslab in plantarflexion or boot with 3 cm heel raise

- Commence early weight-bearing in boot with heel raise

- Use crutches for support

|

Transition phase

2–6 weeks post-injury |

- Remain in boot with heel raise

- Weight-bear as tolerated in boot and gradually wean off crutches

- Perform hip and knee range-of-motion exercises in boot

- Perform static quadriceps and hamstring exercises in boot

- Wear boot while sleeping

- Use a single-leg exercise bike

|

Return-to-activity phase

6–10 weeks post-injury |

- Remove 1 cm heel wedge per fortnight

- Continue to weight-bear as tolerated in boot

- If desired, remove boot for gentle non–weight-bearing range‑of‑motion exercises of the ankle

- If desired, commence swimming, avoiding pushing off the wall and avoiding diving

|

Prevention phase

10–12 weeks post-injury |

- Remove heel lift

- Commence gentle dorsiflexion stretching

- Commence graduated resistance exercises

- Commence cycling, elliptical machine, walking and swimming

- Commence closed chain exercises and functional activities

|

Active rehabilitation phase

12 weeks post-injury and onwards |

- Remove boot

- Commence open chain exercises and functional activities

- Progress range of motion, strength and proprioception

- Commence plyometric training

- Commence sports-specific retraining

|

Tendinopathy and functional lengthening of the Achilles tendon

The term ‘Achilles tendinopathy’ encompasses a variety of pathologies characterised by pain and swelling in and around the Achilles tendon. Tendinopathy can have an acute or insidious onset. Achilles tendon overuse injuries are common in runners, with an annual incidence of between 7% and 9% in high-level runners.18 Notable short-term improvements have been seen with early referral to an experienced allied health practitioner such as a podiatrist or qualified sports physiotherapist.19 It may also be appropriate to refer patients to an exercise physiologist once a diagnosis is made, if a podiatrist or physiotherapist is not available, and many rural or regional exercise physiologists work in conjunction with a remote allied health team. Patients can access a chronic disease management plan under the Medicare Benefits Schedule if the condition has been present for >6 months. Most public hospital outpatient physiotherapy and podiatry departments also accept referrals for Achilles tendinopathy and related conditions. Early rehabilitation for chronic tendinopathy includes reduction in load (such as reducing running volume) and commencement of isometric exercises followed by strengthening exercises such as weighted calf raises.20

Patients may present in a delayed manner after an acute Achilles tendon rupture, sometimes months following the initial injury. A delay in presentation may be due to an individual patient not seeking medical care or misdiagnosis by the initial treating clinician. Management of a delayed presentation of an Achilles rupture and intractable Achilles tendinopathy are similar, and a referral to a sport and exercise physician (a recognised specialty in the Australian healthcare system) or orthopaedic surgeon is appropriate. Injections of steroid or platelet-rich plasma have a limited evidence base.21 Failing six months of non-operative treatment, surgery may be considered. Transfer of the flexor hallucis longus tendon is reserved for severe cases of Achilles tendinopathy, the development of functional lengthening after a rupture or delayed presentation after an acute rupture.22

Insertional Achilles tendinopathy

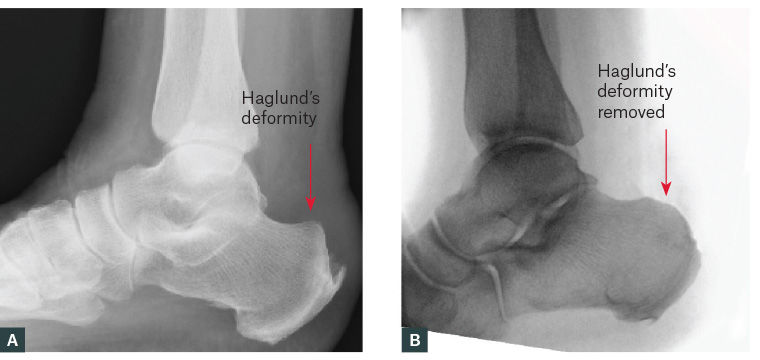

Insertional Achilles tendinopathy is often a combination of retrocalcaneal bursitis, symptomatic Haglund’s deformity and calcific deposits within the substance of the Achilles tendon close to the insertion point of the calcaneum. Chronic tightness of the Achilles tendon or calf musculature results in traction at the calcaneum, pulling the tendon insertion into the calcaneum.23 A Haglund’s deformity is a bony prominence seen on the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity (Figure 4). A tight Achilles tendon can rub on the prominent bone, causing an inflamed retrocalcaneal bursa. This presents as heel pain, exacerbated by physical activity such as walking or running. Patients report pain from direct palpation of the calcaneal tuberosity. X-ray and ultrasonography can show calcific deposits within the Achilles tendon as well as a Haglund’s deformity.

Figure 4. A. Haglund’s deformity; B. Surgical removal of Haglund’s deformity

Non-operative management can be as simple as avoidance of shoes that place pressure on the heel. Podiatry referral may be warranted for patients requiring adjustment of specific work shoes such as steel-capped boots. Rehabilitation, provided by an experienced allied health practitioner such as a podiatrist or physiotherapist, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful in the acute setting. Rehabilitation involves addressing the contracted Achilles tendon and calf, reducing compression on the inflamed tendon then starting a strengthening program once acute inflammation settles. Patients may also benefit from a small heel lift in the shoe, or wearing shoes with a slight heel to reduce compression on the tendon.24

For cases refractory to non-operative management, surgery can be beneficial. This involves an open debridement of the Achilles tendon, excision of the Haglund’s deformity and removal of the inflamed retrocalcaneal bursa (Figure 4).

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus

A common complication of acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon or associated surgery is deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The rate of DVT in acute ruptures and surgery for chronic conditions has been reported as 2.67%,25,26 and the rate of pulmonary embolus has been reported as 1.77%.26 The clinician needs to be wary of the elevated risk of DVT in this population, particularly after a period of immobilisation. Routine use of chemoprophylaxis for DVT prevention is not indicated after acute rupture unless the patient has a specific thrombophlebotic condition such as Factor V Leiden disease.27 However, patients are encouraged to weight-bear when possible and are educated about re-presentation in the setting of calf pain, shortness of breath or chest pain.

Summary

Acute and chronic conditions of the Achilles tendon are a common presentation. For acute ruptures, immobilisation in plantarflexion helps facilitate successful non-operative management when functional rehabilitation protocols are followed. Chronic tendinopathies, functional lengthening or rerupture usually can be treated with non-operative management. For refractory cases, a flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer is an effective, reliable procedure for chronic pathology of the Achilles tendon. Clinicians need to be wary of the elevated risk of DVT and pulmonary embolus in the acute and post-operative setting.

Key points

- Acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon can be successfully managed non-operatively.

- Chronic conditions respond well to rehabilitation in the majority of cases.

- A multidisciplinary approach to management is encouraged.