Oral and maxillofacial pathology encompasses a multitude of diverse conditions and presentations that can be daunting when one is confronted by the exhaustive list and classification of diagnostic possibilities. The structured and comprehensive list of benign and malignant mucosal disease and jaw pathology has more than one hundred different diagnostic possibilities. Listing all these possibilities is potentially more of a hindrance than a benefit for the general practitioner (GP) when a patient opens their mouth to demonstrate their clinical problem.

The oral cavity is home to multiple types of tissue. Pathological conditions can originate from any of these, including mucosa, minor and major salivary glands, muscle, nerves, vessels, bone, teeth and periodontal structures. The ‘surgical sieve’ is as helpful for the clinician for formulating a list of differential diagnoses in the oral cavity as it is elsewhere in the body. The diagnosis may be congenital or acquired. Acquired oral cavity conditions may be traumatic, infective/inflammatory, neoplastic, cystic, autoimmune/allergic, vascular, endocrine, degenerative, idiopathic or nutritional. The starting letter of each of these acquired causes forms the mnemonic ‘TIN CAVED IN’.

Rather than presenting oral pathological conditions according to this structure, the authors have chosen to highlight the common benign and malignant mucosal disease and jaw pathology by grouping them according to their clinical presentation. It is hoped that this will provide the reader with a narrow list of differential diagnoses and assist with stratifying urgency of referral to either an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or oral medicine specialist. Broadly speaking, oral pathology can present as a mucosal surface lesion (white, red, brown, blistered or verruciform), swelling present at an oral subsite (lips/buccal mucosa, tongue, floor of mouth, palate and jaws; discussed in an accompanying article by these authors)1 or symptoms related to teeth (pain, mobility). The last of these presentations has been excluded from this article as it is assumed that a patient with symptoms related to teeth is more likely to present to their dentist than their GP.

The most commonly encountered mucosal surface lesions are those of an epithelial break (ulcer) or an alteration in thickness, texture or colour (white, red or pigmented lesion).

The ulcerated lesion

An ulcerated lesion is most commonly traumatic or immunological (aphthous) in origin; however, the most important lesion to exclude is an oral malignancy. Other, less common, possible causes of an ulcer are infective (bacterial or fungal) and immune-related causes (eg inflammatory bowel disease). The ‘ulcer’ could also represent the residual appearance of the mucosa in an autoimmune vesiculobullous or blistering condition after the blister has ruptured. Persistence, as opposed to episodic recurrence, of an ulcer is an importance feature. Mucosal turnover should occur in <10 days;2 therefore, any persistent ulcer that has been present for ≥2 weeks should be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or oral medicine specialist for biopsy.

Traumatic ulcer

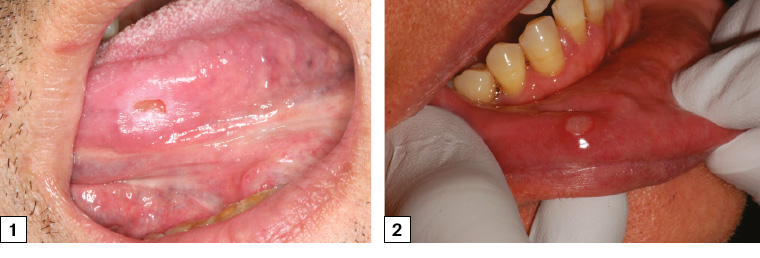

The most common oral ulcer is one caused by trauma. This trauma is most often mechanical (eg biting) but may also be from thermal, radiation or chemical means. The characteristic symptoms of inflammation, pain, redness and swelling are often present, and the central part of the ulcer may be covered by a yellow-white fibrinous exudate (Figure 1).

The cause must be addressed if possible, and review to ensure mucosal healing within two weeks is recommended. If the ulcer persists beyond this period, referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon should be undertaken.

Aphthous ulcer

Recurrent aphthous ulceration (otherwise known as recurrent aphthous stomatitis [RAS]) affects 20–50% of the population3 and presents as painful, recurrent ulcers that almost always affect non-keratinised oral mucosa (buccal mucosa, floor of mouth, vestibule of the lips, soft palate and tongue). The aetiology of RAS is unknown but is thought most likely to be immunologically mediated.4 There are three recognised clinical subtypes based on their clinical presentation: minor (most common), major and herpetiform.

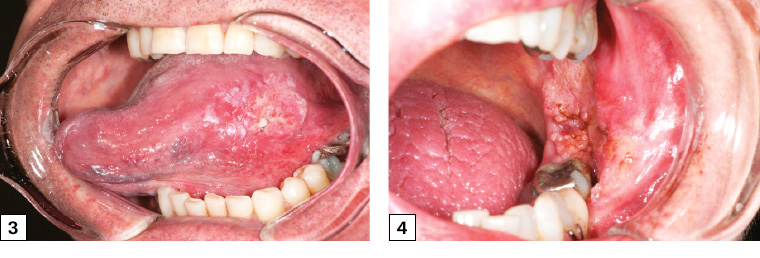

Minor aphthous ulcers are oval shaped and <10 mm in size, frequently last 5–10 days and heal without scarring (Figure 2).

Major aphthous ulcers are variably shaped and >10 mm in size, can last up to six weeks and can heal with scarring. They can resemble an ulcer of an early malignancy.

Herpetiform aphthous ulcers are numerous 1–2 mm diameter ulcerations that may coalesce and are not restricted to non-keratinised oral mucosa. They heal in 1–2 weeks.

Aphthous-like ulceration can be associated with haematinic deficiency or gastrointestinal or rheumatological disease. Vitamin B12, folic acid or iron deficiency can also be associated with RAS in a small proportion of patients, and these nutritional markers should be checked and corrected in this subgroup.

Topical corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone 1% cream or ointment 2–3 times daily after meals, commenced within 24 hours of onset of the aphthous episode can shorten the duration of the symptoms.5

Figure 1. Symptomatic traumatic ulceration of the left mid-ventral tongue associated with a sharp left lower molar. The ulcer has flat edges and is surrounded by an area of frictional keratosis. The ulcer was soft on palpation.

Figure 2. Minor aphthous ulceration of the lower right labial mucosa with typical erythematous hallow and yellow base

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

There were approximately 3800 newly diagnosed cases of head and neck cancers in Australia in 2019, with oral cancer comprising just over half of these cases.6 More than 90% of oral cancers are oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); other tumours are minor salivary gland carcinomas, sarcomas and odontogenic malignancies.7 Oral cavity (as distinct from the oropharynx) subsites are defined as the lips, tongue, floor of mouth, buccal mucosa, retromolar trigone, maxillary and mandibular alveolus and hard palate. The major risk factors for oral cavity SCC are smoking,8 alcohol consumption of >3 standard drinks per day9 and betel quid (paan) consumption.

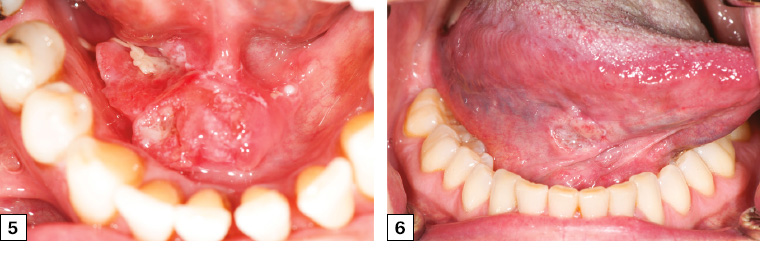

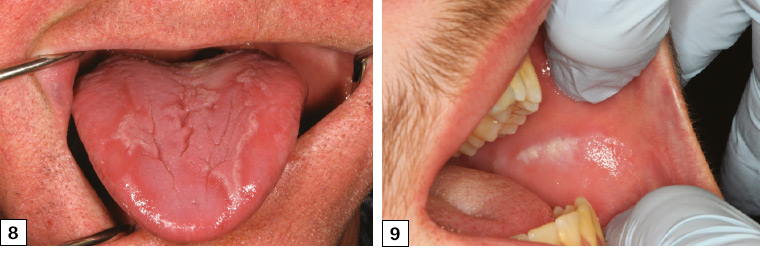

Oral SCC most commonly presents as a non-healing ulcer, which can be indurated/firm and have irregular margins and raised, rolled edges (Figures 3–6). As SCC invades adjacent structures in the oral cavity, it may result in neurosensory change (paraesthesia or anaesthesia) and tooth mobility. In late stages, it may cause alteration of speech and swallowing. It is important to note that oral SCC may not necessarily be painful, and pain is not used to differentiate between a potentially malignant or benign cause of an ulcer. In addition, oral SCC is found across virtually all age groups (including paediatric, although rarely), and up to 10% of SCCs are diagnosed in patients who do not smoke or drink alcohol.10 Therefore, the absence of risk factors does not rule out the possibility of malignancy.

If an ulcer is suspected to have any suspicious malignant features, then immediate referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or specialist unit in a tertiary hospital is indicated. A tissue diagnosis is established, followed by completion of staging (computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], ultrasonography +/– positron emission tomography [PET]). Patients should be managed by a multidisciplinary head and neck tumour team.

Figure 3. Left lateral tongue squamous cell carcinoma with irregular margins, heterogeneous appearance and raised, rolled edges. The cancer was palpably firm and indurated, unlike normal tongue tissue.

Figure 4. Left buccal/retromolar trigone squamous cell carcinoma. The lesion had characteristic rolled edges with irregular margins and likely invasion of the posterior mandible, as the lower left molar was mobile. The lesion was initially attributed to cheek biting, which resulted in a delay in referral for several months.

Figure 5. Right floor of mouth squamous cell carcinoma crossing the midline with heterogeneous appearance and irregular margins. The lesion was firm and nodular on palpation.

Figure 6. Early-stage right tongue squamous cell carcinoma in a female patient who did not smoke who presented with a six-week history of a slightly sore right tongue and persistent ulcer. The cancer had irregular margins and heterogeneous appearance and was referred early by her general practitioner.

The primary curative management of oral cavity SCC is surgery, with radiotherapy and chemotherapy used as adjunctive therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence. The role of immunotherapy in the management of oral SCC is currently being established through clinical trials and is only potentially accessible in Australia for patients with recurrent inoperable or metastatic oral SCC.

Lip carcinomas are more closely aligned in their aetiology and behaviour with facial skin cancer, the primary risk factor being chronic ultraviolet exposure. Lip cancer typically presents as a non-healing ulcer on the vermillion of the lower lip (Figure 7). The management of lip cancer is primarily surgical excision.

Figure 7. Lower right lip squamous cell carcinoma presenting as a persistent ulceration with crusting. Note the presence of adjacent sun-related actinic changes across the vermilion zone and border.

White, red and mixed lesions

Changes in thickness, texture and colour of the oral mucosa can present an array of white and/or red lesions. Causes of these presentations include variations of normal, frictional causes, infectious causes, immune-mediated causes and pre-malignant and malignant changes. The presence or absence of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the malignant potential of a lesion. In this article, the authors outline a short list of more commonly occurring conditions that can present as non-ulcerative mucosal changes.

Geographic tongue (erythema migrans)

Geographic tongue is, as its name suggests, the appearance of the dorsum of the tongue resembling a changing ‘map of the world’. Areas of red atrophic patches are surrounded by white elevated keratotic margins, giving the appearance of continents surrounded by water (Figure 8). The appearance changes over several days, much like the rotation of a spinning globe of the world.

The condition is almost always asymptomatic, and management consists of reassurance and explanation alone.

Frictional keratosis

Frictional keratoses occur in oral cavity subsites that are subjected to chronic low-grade trauma. The buccal mucosa at the occlusal line (cheek-biting), lower lip vestibule, lateral tongue and edentulous ridges (where mastication of food makes contact with the ridge) are common sites. The lesion is often slightly textured and white, and takes on the shape or outline of the traumatic cause (Figure 9).

Figure 8. The alternating red atrophic areas surrounded by the white raised hyperkeratotic areas typical of geographic tongue

Figure 9. Linear frictional keratosis of the right buccal mucosa corresponding to the occlusal plane where the upper and lower dentition meet

Oral candidiasis

Oral candidiasis is an opportunistic fungal infection usually caused by Candida albicans that arises in a patient with one or more local or systemic predisposing factors. Local factors include poor oral hygiene, xerostomia and the use of a removable prosthesis (denture). Systemic predisposing factors include immunodeficiency, diabetes mellitus, antibiotic use, steroid therapy (including inhaled steroids), chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

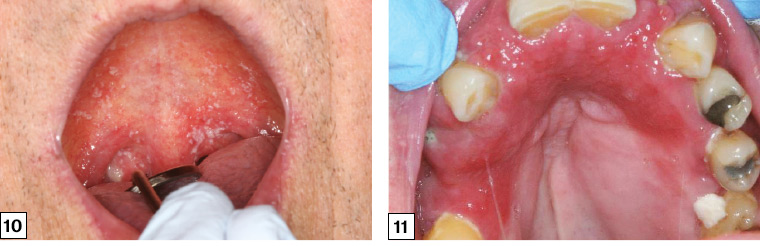

There are three common forms of oral candidiasis: pseudomembranous, erythematous and chronic hyperplastic. The typical clinical presentation is the acute pseudomembranous form (thrush; Figure 10). It presents as increasingly confluent white colonies and plaques that can be wiped away, leaving a painful erythematous undersurface. It is most commonly found in the oropharynx and buccal mucosa, and in the early stages it is minimally symptomatic.

As it progresses, the pseudomembrane may be lost, resulting in a generalised red lesion. Oral candidiasis can be treated with a number of topical or systemic antifungal preparations. Diagnosis is made clinically, and a smear or culture may be undertaken to confirm the presence of fungal hyphae or high colony forming units to support a finding of pathology over commensalism’.11 If the hyperplastic form is suspected, a biopsy is often warranted.

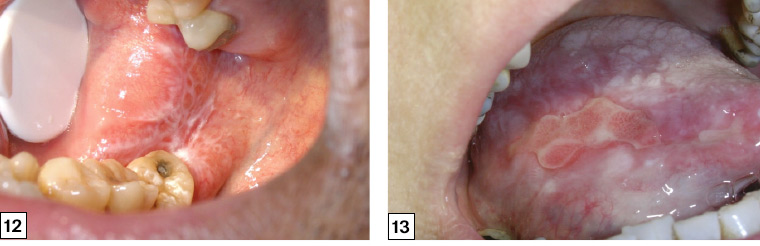

Denture-associated erythematous stomatitis is a candida-related condition often associated with the use of a removable oral prosthesis (denture). It is most commonly diagnosed on the hard palate, where the palatal mucosa and the upper denture are in contact. This appears as a bright red area that corresponds to the area of the denture, sometimes with papillary areas within it (Figure 11). This presentation is often asymptomatic and carries no risk of malignant potential.

Initial treatment of denture-associated erythematous stomatitis focuses on improvement of oral and denture hygiene as well as removal of the prosthesis during sleep.12 Dentures should be stored dry when not worn and can be soaked initially daily and then weekly for 15 minutes in a dilute white vinegar solution. If the patient has concerns regarding the fit of the removable prosthesis, they should be encouraged to see their dental prosthetist or dentist to review their denture.

Figure 10. Oral pseudomembranous candidosis of the palate

Figure 11. Denture-associated erythematous stomatitis of the upper palate and alveolus with a papillary appearance anteriorly. The outline of the mucosal change corresponds to the fitting surface of the upper maxillary denture.

Oral lichen planus

Oral lichen planus is a chronic, immune-mediated mucosal condition that affects up to 2% of the population, with a slight female predilection.13 It can be accompanied by cutaneous or other mucosal site involvement. The aetiology is unknown. The clinical appearance can vary depending on clinical subtype: reticular (most common), erosive and plaque-like forms. Multiple subtypes may be observed in a single patient.

The reticular type is characterised by interlacing white lines that produce a ‘net-like’ pattern (Wickham’s striae). This is most commonly located on the buccal mucosa but can be found on the tongue and lip vestibule (Figure 12).

In the erosive form of oral lichen planus, there may be areas of complete mucosal breakdown resulting in ulceration often accompanied by areas of atrophy and erythema (Figure 13). With careful inspection, the area surrounding the erosive ulcer often presents with keratotic striae, but it can resemble an oral malignancy. Ulceration in oral lichen planus should not feel firm on palpation. This erosive form should always be referred to an oral medicine specialist or maxillofacial surgeon for further assessment and biopsy.

The majority patients with oral lichen planus are asymptomatic, and no treatment is required. If the condition is symptomatic or erosive, referral to an oral medicine specialist for the commencement of topical or, in certain cases, systemic immunosuppressive agents is indicated.

Figure 12. ‘Wickham’s striae’ of oral lichen planus on the right buccal mucosa extending across the retromolar pad presenting as a lace- or net-like pattern of keratotic lines on a faint erythematous background

Figure 13. Erosive oral lichen planus presenting as a large ulceration on the right lateral tongue. Ulceration is often persistent and must be differentiated from an oral malignancy.

Oral submucous fibrosis

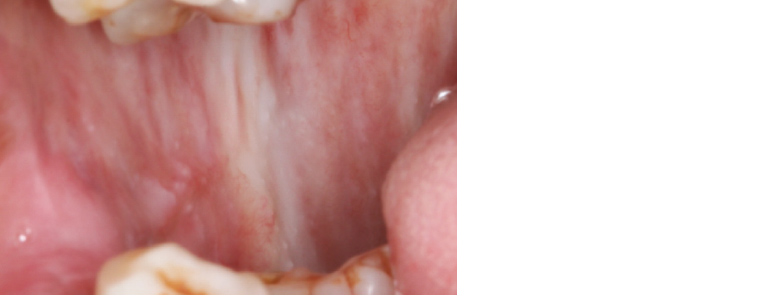

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a potentially malignant disorder characterised by fibroelastic change and epithelial atrophy of the oral mucosa, which results in stiffness of the oral mucosa and trismus (inability to open the mouth). The major risk factor is areca nut (betel quid) chewing, which is most common in South and South East Asian countries.14 The changing patterns of migration to Australia have resulted in increasing cases of OSMF. The condition is characterised by progressive restriction of mouth opening, blanching of the mucosa and a ‘guitar string’ sensation when palpating the buccal mucosa, as well as depapillation of the tongue and loss of pigmentation of the mucosa (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Oral submucous fibrosis associated with betel quid chewing. Palpable fibrous banding is present in the submucosa across the right buccal mucosa, restricting oral opening.

The correct diagnosis of OSMF is important as it is a potentially malignant disorder, with malignant transformation rates reported ranging from approximately 2% to 9%.15,16

Management consists of cessation of areca nut chewing, modification of other risk factors and ongoing surveillance to ensure an early diagnosis of oral SCC should it develop.

Leukoplakia

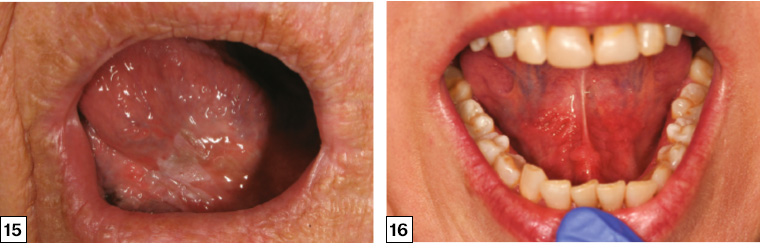

Leukoplakia is a descriptive term used to describe ‘white plaques of questionable risk having excluded (other) known diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer’ affecting the oral mucosa (Figure 15).17

As leukoplakia is a descriptive term rather than a microscopic tissue diagnosis; a biopsy is mandatory to establish the diagnosis. The tissue diagnosis may range from benign (eg hyperkeratosis) to pre-malignant (dysplasia) to malignant (SCC). A recent systematic review showed that there was a malignant transformation rate of 0.13–34% reported for oral leukoplakic lesions across 24 studies.18 It is therefore imperative that any leukoplakic lesion is referred for assessment and biopsy.

Oral dysplasia is a histopathological diagnosis rather than a clinical descriptive term. The histopathological discovery of dysplasia is the best tool available to the treating clinician for risk stratification of the development of oral SCC, and it may guide treatment options towards excision over watchful monitoring. Any lesions with biopsy-proven dysplasia should be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or oral medicine specialist for appropriate management, which may vary depending on the patient, lesion extent and risk factors.

The red lesion: Erythroplakia

Erythroplakia is the ‘red’ counterpart to the white leukoplakic lesion (Figure 16). It is a clinical term that refers to a red patch of the oral mucosa or a red lesion that cannot be characterised clinically or pathologically as any other definable lesion or disease.19 The erythroplakic lesion is of even greater cause for concern for the treating clinician than a white leukoplakic lesion as there are studies showing an almost 90% rate of SCC/high-grade dysplasia when a tissue diagnosis is established.20

It is therefore imperative that every erythroplakic lesion in the oral cavity is referred for urgent assessment and biopsy.

Figure 15. Leukoplakia of the ventral tongue. Incisional biopsy showed severe dysplasia, and the lesion was subsequently completely excised.

Figure 16. Erythroplakia of the bilateral floor of the mouth presenting as a diffuse, painless, ‘velvety’ red patch. This lesion harboured severe dysplasia.

Key points

- The vast majority of oral mucosal and jaw conditions are benign and amenable to surgical, medical or dental treatment.

- The possibility of an oral cavity malignancy should always be considered, particularly with the presentation of a non-healing ulcer, a bleeding lesion or an area of mucosa that persistently appears red or white.

- Any persistent ulcer that has been present for ≥2 weeks should be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or oral medicine specialist for biopsy.

- Leukoplakia and erythroplakia are clinical terms used to describe oral white and red patches respectively that cannot be scraped off and cannot be ascribed to any disease or condition. Referral for biopsy is mandatory as a significant proportion of these lesions will be dysplastic or malignant.

- Any tissue excised from the oral cavity should be sent for histopathological examination as the clinical appearance alone is insufficient to ensure a correct diagnosis.