‘Doctors are doctors, and dentists are dentists, and never the twain shall meet’, writes Julie Beck in The Atlantic.1 She notes that doctors rarely ask if you floss your teeth, and dentists rarely ask if you exercise, concluding, ‘The divide sometimes has devastating consequences’.1 But why is it so? Dental problems present in many aspects of medicine, particularly general practice and emergency departments. Medicine is a broad field, comprising some 23 recognised specialties and 86 recognised specialist titles.2 Most medical specialties are organised by organ systems, so why not include the oral health system that is examined in dentistry? Beck observes, ‘The body didn’t sign on for this arrangement, and teeth don’t know that they’re supposed to keep their problems confined to the mouth’.1

This article explores the historical reasons for the divide between medicine and dentistry, and some of the challenges this raises in modern healthcare. These issues are particularly relevant in regional, rural and remote Australia, where there is a shortage of all health professionals, including doctors and dentists.

Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–20243 identifies four priority population groups with poorer oral health and access to care than the general population. These include people who are socially disadvantaged or on low incomes, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, people from regional and remote areas, and people with additional and/or specialised healthcare needs.

Some rural communities may lack the population base to justify a full-time dentist, hence access to dental services may rely on accessing mobile dental facilities,4 attending intermittent ‘fly-in fly-out’ dental services5 or travelling large distances.6 Patients with dental problems who experience barriers to accessing timely oral healthcare with a dental practitioner may attend general practices,7 emergency departments,7–9 pharmacies10 or Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services.11,12

There were an estimated 750,000 appointments with general practitioners (GPs) for dental problems in Australia in 2011.13 Between 2015 and 2016, there were 67,266 potentially preventable hospitalisations for medical conditions of dental origin, with higher admission rates in more remote areas.14,15 GPs commonly provide pain relief, antibiotics, advice on oral hygiene and referrals to dentists,7,10,16 but primary dental problems often are not definitively resolved, resulting in return visits.17

This issue is global. The World Health Assembly in 2007 recommended oral healthcare and chronic disease prevention programs should be integrated.18 Good oral health is important for good general health. Well-established associations between systemic diseases and dental infections19–21 include clear links between periodontal disease and pregnancy,22 diabetes mellitus,23 preterm and low birth weight babies,24 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,25 renal disease,26 cardiovascular disease26 and stroke.27 Australians living in very remote areas have a higher incidence of periodontal disease (36.3%) than those living in regional centres (22.1%).28 Many patients with co-existing medical and dental issues require integrated care plans involving cooperation of doctors and dentists.29 Such interprofessional collaboration may improve patient outcomes30 and the quality of patient-centred care.31

The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) global policy for advancement of oral health32 recommends training non-dental primary care providers in the management of emergency dental presentations. However, very few GPs or emergency physicians report receiving any instruction in managing dental problems.33–35 Evidence shows GPs are very interested in attending emergency dental postgraduate education.33,34,36–38

Australia’s National Oral Health Plan suggests medical professionals, who regularly consult with families and children, may have a significant educational role in oral health literacy through providing dietary advice and preventive oral healthcare, and encouraging regular dental check-ups.3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthcare workers could also benefit from oral health education.5

Clearly, oral health and emergency dental management should be part of undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula, particularly for GPs and rural doctors.34,38 Governments and professional associations recognise that professional siloes between doctors and dentists are not in the best interests of patient care.39,40 Education is a logical starting point to address concerns that practitioners are siloed in their attitudes to professional practices and protective of their own professional identity.3,41 But are there wider issues that have driven this professional divide?

Dentistry has a fascinating history that provides several clues. Barber surgeons in the Middle Ages provided services such as leeching and dental extractions. Dentistry, before the days of adequate anaesthesia, was seen as the mechanical challenge to repair or extract teeth.1 Lidocaine, introduced in 1948, provided reliable local pain relief, illustrating an example of medicine and dentistry cooperating to improve service provision.42

Recognising the need for formal dental education, two self-trained dentists established the world’s first dental school at Baltimore in 1840 and paved the way for dentistry’s development as a profession.43 They appealed for dentistry to be part of medicine, arguing that dentistry was more than a mechanical skillset and deserved similar status and support to that of medicine. However, their appeal was rejected in a ‘historic rebuff’, because dentistry was deemed as a field of little consequence. Subsequent efforts to integrate the two worlds have also failed.44 Otto suggests organised dentistry also fought to keep the separation for the purpose of maintaining autonomy and professional independence.45

A 1926 Carnegie Foundation review of dental education found ‘entrenched disdain’ for dentistry among medical professionals, who ‘left teeth to the tradesmen’.45 The review argued that, ‘Dentists and physicians should be able to cooperate intimately and effectively – they should stand on a plane of intellectual equality’, noting, ‘Dentistry can no longer be accepted as mere tooth technology’.45

Growing understanding of microbiology led to appreciation of the mouth not just as a vector of disease but also as a reservoir of newly discovered bacteria. Yet dental disease and its connection to medical conditions remained poorly understood, and tooth decay and toothaches were seen as inevitable.45 Funding models, economic pressures and social issues have also driven the divergent paths of the two professions.

Funding arrangements may contribute significantly to the siloed natures of medical and dental care. Medicare provides free hospital care, as well as free or subsidised healthcare services and medications for all Australians. In contrast, dentistry is generally not covered under the Medicare Benefits Schedule, with some exceptions, such as cleft palate surgery and certain government-funded schemes.46 Most of Australia’s dental services are provided by private dental practitioners who charge fees;47 however, private patients may or may not have private dental health insurance.13 Free oral health services are only provided for children and adolescents aged <18 years and for adults with healthcare concession cards.3 Many patients with dental problems see their GPs rather than their dentists as a result of financial or access problems, yet policymakers often consider oral healthcare separately to other medical conditions.18 It is likely that without substantial structural reform to this government/private divide, there will continue to be challenges in implementing policies to improve oral health.48

The economic effect of the Great Depression affected diets and capacity to pay for dental services or even basic items such as toothbrushes and toothpaste. Poor oral health habits learned by children endured for decades and were passed onto their offspring.4 Calcium consumption decreased as dairy products became more expensive, but sugar consumption rose. By 1939, Australian dental and nutritional health was extremely poor. Military dental officers were established in recognition of the importance of dental care for overall medical health (25% of evacuations from the frontline in the Boer War of 1899–1901 were for dental problems).4

Social pressures have also influenced the interconnection between oral health and overall medical health. Having attractive teeth may be an indicator of financial wealth as well as medical health. Beck observes the ‘perfect Hollywood smile is in part because … perfect teeth are a very clear way of signalling your wealth’. The six top front teeth – ‘the social six’ – are indeed a status symbol.1 The ‘dental dowry’, whereby marriageable daughters had all their teeth extracted and replaced with dentures to make them more attractive to potential suitors who might otherwise fear future dental expenses, endured in Australia until well into the 20th century.42

These historical factors – which include social determinants of health and lifestyle issues such as diet, financial pressures affecting access to healthcare and growing emphasis on cosmetic care – still influence both professions today.

Australia can be justifiably proud of its modern medical and dental systems. Otto observed, ‘Centuries of misplaced pride, bad science, and financial interests have made rivals of dentists and doctors’. We have seen how the professions have taken separate paths driven by historical, economic and social pressures. But does it have to be so – and is this divide in the interests of the patients and communities both professions strive to serve?

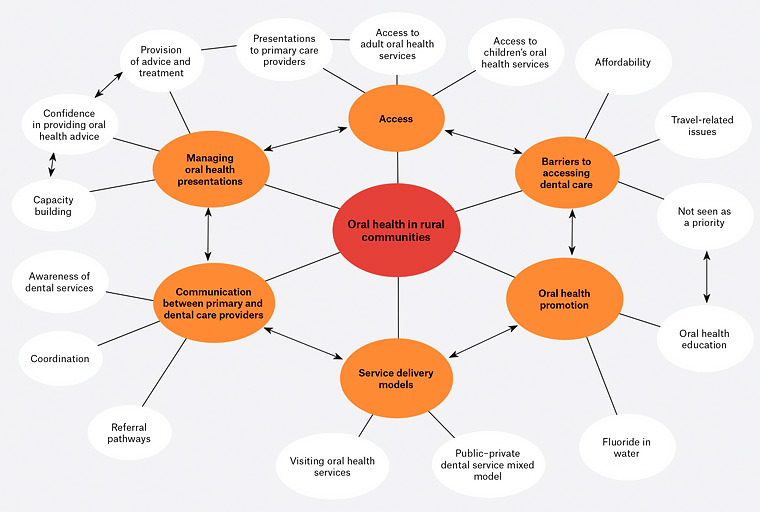

Addressing this issue should start with education at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. While detailed exploration of other solutions is for another day, it needs to consider the complexities of policy, funding and other pressures. A 2016 project explored the issue of oral health in rural communities, identifying many interrelated issues.49 Figure 1 summarises the multiple intersecting factors needed to fully integrate oral health and overall general health including access, barriers to accessing dental care, oral health promotion, service delivery models, communication between primary and dental care teams, and management of oral health presentations.49

Figure 1. Thematic schema representing primary and dental care providers’ perspectives of rural oral health49. Click here to enlarge

Conclusion

Medicine and dentistry have historically evolved separately, with distinct education systems, clinical networks, records, funding and insurance arrangements. Better patient outcomes will be achieved by overcoming this divide. Education is one place to start, including oral health training during undergraduate medical education, and skilling GPs to manage emergency dental presentations, especially in rural and remote regions. Funding and insurance are next, followed by models of care that enable all health – oral and general – to be delivered to all populations, particularly the underserved. Maybe then we can put ‘the mouth back in the body’.45