Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common chronic joint diseases and a leading cause of pain and disability in Australia. A National Osteoarthritis Strategy (the Strategy) was developed to outline a national plan to achieve optimal health outcomes for people at risk of, or with, OA.

Objective

This article focuses on the theme of advanced care of patients with OA within the Strategy.

Discussion

The Strategy was developed in consultation with a leadership group, thematic working groups, an implementation advisory committee, multisectoral stakeholders and the public. This Strategy identified three priorities in advanced care for osteoarthritis. In brief, these include surgical decision making, referral for evidence-informed non-surgical alternatives and surgical services. A set of goals within these priority areas and strategies was also proposed by the working group in consultation with stakeholders nationwide. Peak arthritis bodies and major healthcare professional associations currently endorse the Strategy.

This article is part three in a three-part series on the National Osteoarthritis Strategy.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common chronic joint condition globally and in Australia: one in five Australians over the age of 45 years have OA.1 Nevertheless, the care that patients receive in Australia is fragmented and, in some cases, inappropriate. The National OA Strategy (the Strategy) informs how to better coordinate existing limited health services and deliver more effective and appropriate care. The aim of the Strategy is to outline Australia’s national response to OA, covering three thematic areas: ‘prevention’, ‘living well with OA’ and ‘advanced care’. The methods of developing the Strategy are detailed in part one of the Strategy series.2 The second part of this series focuses on priorities for action for people living with OA.3 This article, part three, focuses on ‘advanced care’.

Limitations of existing decision aids and selection of patients

Total joint replacement (TJR) surgery should be indicated on the basis of evidence-based criteria and only undertaken when appropriate non-operative strategies have failed. Currently, up to one-quarter of TJR surgeries are performed on inappropriate candidates,4 and there are very few predictive tools to help the referring practitioners, especially general practitioners (GPs), determine which patients are likely to be good or poor responders to surgery. According to previous patient selection criteria for the appropriateness of TJR, 20–45% of the patients were considered ‘uncertain’;5 therefore, these tools are difficult to use in daily practice. Most orthopaedic surgeons recognise the need for a decision aid embedded with effective communication tools to facilitate shared decision making with patients and other care providers across disciplines.6 However, there are concerns about the use of mandatory cut-off points for patient-reported outcomes and the medico-legal implications of using such decision aids.7 In addition, an audit to evaluate clinical effectiveness and collect user feedback of the decision aid may be necessary for surgeons to gain confidence in its legitimacy.

Perceived insufficient non‑operative alternatives

There is a perceived lack of non-operative alternatives for the management of severe OA by Australian surgeons.7 Despite studies showing pre-operative physiotherapy8 – consisting of structured patient education, exercise and weight loss programs9 – significantly reduced joint symptoms in people with knee/hip OA awaiting TJR, the uptake of pre-operative interventions remains low in Australia. A survey showed only 20% of people on orthopaedic waitlists have tried exercise or weight loss within the preceding five years before being placed on the waiting list (MD & PC, unpublished data). There is a substantial need for clinicians to provide or refer to optimal conservative care as per evidence-based guidelines10,11 pre-operatively, even after a patient has been scheduled for surgery (refer to part two of the Strategy series on ‘living well with OA’ for examples of existing non-surgical OA management services).3

Issues with the waiting list for joint replacement

A key priority for the Commonwealth Government is to provide timely access to TJR surgery for OA. However, several challenges exist, such as difficulty in obtaining appropriate surgical referrals, long waiting periods and limited availability of specialists in remote areas. The current three-tiered (urgent, semi-urgent and non-urgent) TJR surgery priority system is relatively unstructured and insensitive to the individual’s need.12 Several tools have been developed for the determination of clinical urgency of TJR for people with OA, but the validity and reliability warrant further investigation. For example, the Western Canada Waiting List Project tested a TJR priority criteria tool showing the high and low categories of urgency were well discriminated; however, an overlap was found between adjacent urgency categories.13 An Australian Multi-attribute Arthritis Prioritisation Tool (MAPT) was used in Victoria, but evidence shows that the MAPT score was not well associated with radiographic severity of OA and waitlist priority category.14 Additionally, patients waiting for surgery should be routinely reviewed by GPs and surgeons as appropriate to detect and prevent potential rapid physical or psychological deteriorations.15

Priorities and strategic responses

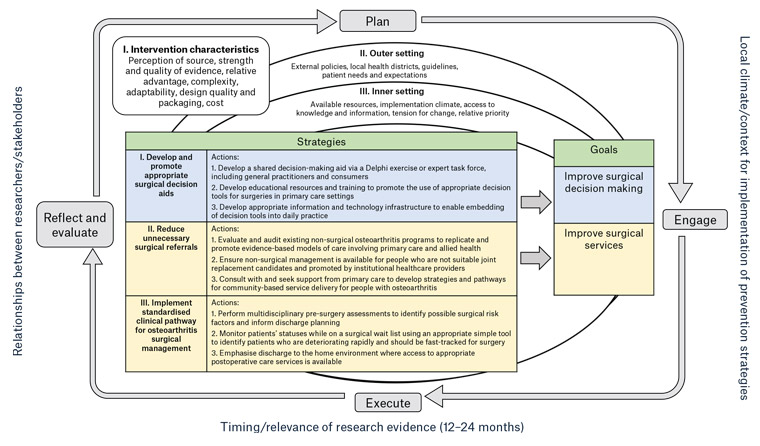

The evidence provided in the previous section served as the evidence basis for the determination of priority areas of the Strategy. Three priorities have been identified by the advanced care working group. Actionable strategies to address the priorities and achieve the proposed impact (goals) are proposed on the basis of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Figure 1). 16 The OA Strategy leadership group are currently developing business plans for each of the key strategies and initiating advocacy work with major organisations (eg Department of Health, Arthritis Australia, Sport Australia) to facilitate the implementation of the key actions.

Figure 1. The Strategy’s proposed framework for the implementation of strategies and actions required for advanced care of osteoarthritis. Click here to enlarge

Figure adapted from Wolk et al17 and based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).18

The full document including detailed implementation plans for each strategy to address the priorities of the advanced care working group is available online (https://ibjr.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/National-Osteoarthritis-Strategy.pdf).

Competing interests: DJH reports personal fees as a consultant (advisory boards for Pfizer, Merck Serono, TLC Bio and Flexion), outside the submitted work. PC reports personal fees from Stryker, Johnson & Johnson and Kluwer, and grants from Medacta, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Funding: None.

Acknowledgements

The National Osteoarthritis Strategy is endorsed by Arthritis Australia, the Australian Rheumatology Association, The Australian Orthopaedic Association, The Australasian College of Sport and Exercise Physicians and The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. The authors acknowledge the funding support from the Medibank Better Health Foundation and The Australian Orthopaedic Association. The authors had full access to all relevant data in this study; the supporting sources had no involvement in data analysis and interpretation, or in the writing of the article.

Professor David J Hunter holds a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Practitioner Fellowship. Associate Professor Michelle Dowsey holds an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1122526). Professor Peter Choong holds an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (APP1154203). Professors Peter Choong, Philip Clarke, Jane M Gunn, Peter O’Sullivan and Associate Professor Dowsey are recipients of an NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence grant in Total Joint Replacement (APP1116325). Professor Anita Wluka holds an NHMRC Translating Research into Practice Fellowship (APP1150102).

Did you know you can now log your CPD with a click of a button?

Create Quick log

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Osteoarthritis. Canberra, ACT: AIHW, 2018. Available at www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoarthritis/contents/impact-of-osteoarthritis [Accessed 29 January 2020]. Search PubMed

- de Melo LRS, Hunter D, Fortington L, et al. National Osteoarthritis Strategy brief report: Prevention of osteoarthritis. Aust J Gen Pract 2020;49(5):272–75. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-08-19-5051-01. Search PubMed

- Eyles JP, Hunter DJ, Briggs AM, et al. National Osteoarthritis Strategy brief report: Living well with osteoarthritis. Aust J Gen Pract 2020;49(7):438–42. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-08-19-5051-02. Search PubMed

- Cobos R, Latorre A, Aizpuru F, et al. Variability of indication criteria in knee and hip replacement: An observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:249. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-249. Search PubMed

- Riddle DL, Jiranek WA, Hayes CW. Use of a validated algorithm to judge the appropriateness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: A multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(8):2134–43. doi: 10.1002/art.38685. Search PubMed

- Adam JA, Khaw FM, Thomson RG, Gregg PJ, Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Patient decision aids in joint replacement surgery: A literature review and an opinion survey of consultant orthopaedic surgeons. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008;90(3):198–207. doi: 10.1308/003588408X285748. Search PubMed

- Bunzli S, Nelson E, Scott A, French S, Choong P, Dowsey M. Barriers and facilitators to orthopaedic surgeons’ uptake of decision aids for total knee arthroplasty: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017;7(11):e018614. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018614. Search PubMed

- Abbott JH, Wilson R, Pinto D, Chapple CM, Wright AA. Incremental clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of providing supervised physiotherapy in addition to usual medical care in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: 2-year results of the MOA randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27(3):424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.12.004. Search PubMed

- Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. Total knee replacement and non-surgical treatment of knee osteoarthritis: 2-year outcome from two parallel randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018;26(9):1170–80. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.04.014. Search PubMed

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis. 2nd edn. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2018. Search PubMed

- Brand C, Osborne RH, Landgren F, Morgan M. Referral for joint replacement: A management guide for health providers. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2007. Search PubMed

- Osborne R, Haynes K, Jones C, Chubb P, Robbins D, Graves S. Orthopaedic waiting list project: Summary report. Melbourne, Vic: Victorian Government Department of Human Services, 2006. Search PubMed

- Noseworthy TW, McGurran JJ, Hadorn DC. Waiting for scheduled services in Canada: Development of priority-setting scoring systems. J Eval Clin Pract 2003;9(1):23–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00377.x. Search PubMed

- David VM, Bousounis G, Kapakoulakis T, Champion R, Masman K, McCullough K. Correlation of MAPT scores with clinical and radiographic assessment of patients awaiting THR/TKR. ANZ J Surg 2011;81(7–8):543–46. Search PubMed

- Ostendorf M, Buskens E, van Stel H, et al. Waiting for total hip arthroplasty: Avoidable loss in quality time and preventable deterioration. J Arthroplasty 2004;19(3):302–09. Search PubMed

- Keith RE, Crosson JC, O’Malley AS, Cromp D, Taylor EF. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implement Sci 2017;12(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7. Search PubMed

- Wolk CB, Jager-Hyman S, Marcus SC, et al. Developing implementation strategies for firearm safety promotion in paediatric primary care for suicide prevention in two large US health systems: A study protocol for a mixed-methods implementation study. BMJ Open 2017;7(6):e014407. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014407. Search PubMed

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. Search PubMed

Download article