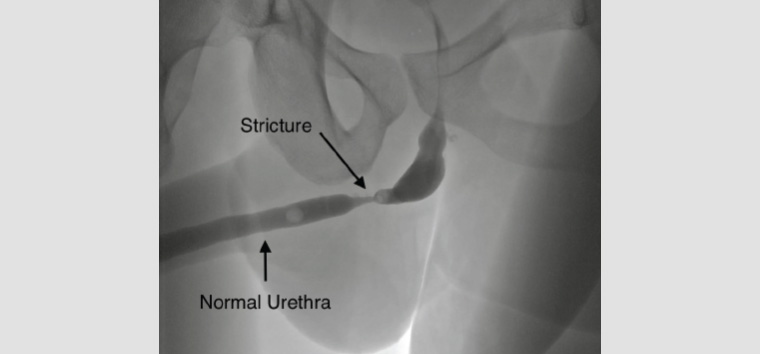

A urethral stricture is an abnormal narrowing of the urethral lumen (Figure 1).1 With a worldwide prevalence ranging from 0.2% to 0.9%, urethral strictures are an often-forgotten cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).2 Quality of life is reduced by urethral strictures, with many patients experiencing recurrent urinary tract infections, bothersome LUTS and progression to acute urinary retention.3,4

Figure 1. Voiding cystourethrogram displaying a bulbar urethral stricture with associated proximal dilatation

The general practitioner (GP) is often the first point of contact for men affected by LUTS. While there are numerous causes of LUTS for the GP to consider (Table 1), early recognition and prompt referral to a urologist are crucial for reducing the morbidity from a urethral stricture.

| Table 1. Causes of male lower urinary tract symptoms |

| Obstruction |

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Tumour (eg bladder, prostate)

- Urethral stricture

- Foreign body

|

| Non-neurogenic overactive bladder |

- Post-operative pelvic surgery

- Bladder calculi

|

| Infection |

- Urinary tract infection

- Urethritis

- Prostatitis

|

| Diuretic |

- Diabetes

- Nocturnal polyuria

- Medications

|

| Neurogenic overactive bladder |

- Cerebrovascular accident

- Parkinson’s disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Spinal cord injury

|

| Other |

- Distal ureteric calculi

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

|

Aetiology

The aetiology of urethral strictures is broad and complex but frequently remains unknown because of a delay between the precipitating event and development of symptoms. In developed countries, the most common causes of urethral strictures are iatrogenic and idiopathic, whereas trauma (eg pelvic fracture) is the most common cause in developing countries.5 Iatrogenic injuries (eg insertion of indwelling urinary catheters, transurethral surgery, radiation therapy for prostate cancer) have been reported to account for up to 45% of cases for which an instigating event is known.6,7 Idiopathic strictures include those occurring at any age and at any site with no known cause. Other causes include infection (eg gonorrhoea, chlamydia, non-specific urethritis), lichen sclerosus (ie balanitis xerotica obliterans), hypospadias and malignancy.6 All of these processes can lead to scar tissue formation; scar tissue contracts and thereby reduces the calibre of the urethral lumen.

Currently, lichen sclerosus is the most common identifiable cause of penile strictures in young and middle-aged men.8 It causes atrophic fibrosis and is thought to be autoimmune in nature, although an infective aetiology has also been proposed. Typically, lichen sclerosus begins as an itchy white patch on the inner aspect of the foreskin or glans (Figure 2). Subsequent scarring around the meatus produces stenosis that can spread proximally into the penile urethra, resulting in urethral stricture formation.

Figure 2. Images of lichen sclerosus

A. Penile skin; B. Glans penis

Stricture aetiology is closely linked with its location within the male urethra.9 For example, traumatic strictures tend to be located in bulbar and posterior urethral segments. Alternatively, strictures secondary to hypospadias and lichen sclerosus typically arise in the penile urethra. A summary of the different anatomical locations of urethral strictures with their corresponding aetiologies and urethroplasty techniques is provided in Table 2.

| Table 2. Urethral stricture locations with corresponding aetiologies and urethroplasty techniques |

| Urethra location |

Stricture aetiology |

Urethroplasty technique |

| Fossa navicularis |

Lichen sclerosus or non-traumatic |

Single-stage repair using oral mucosa graft (OMG) |

| Penile urethra |

Lichen sclerosus or non-traumatic |

Single-stage repair using OMG |

| Hypospadias |

Single- or two-stage repair using prepucial skin, OMG and/or local tissue flap |

| Traumatic |

Single- or two-stage repair using prepucial skin, OMG and/or local tissue flap |

| Bulbar urethra |

Lichen sclerosus |

Single-stage repair using OMG via a dorsal, ventral or double face approach |

| Traumatic |

Anastomotic urethroplasty |

| Non-traumatic |

Non-transecting anastomotic urethroplasty OR single-stage repair using OMG – dorsal, ventral or double-face approach |

| Devastated urethra or necrosis |

Replacement with pedicled preputial tube or bowel segment |

| Posterior urethra |

Traumatic |

Stepwise anastomotic urethroplasty |

| Radiation related |

Single-stage repair using OMG and/or local tissue flap |

Clinical manifestations

Typically, LUTS such as hesitancy, weak urinary stream, straining and incomplete bladder emptying are the initial clinical features of a urethral stricture.10 However, acute urinary obstruction necessitating urgent transurethral or suprapubic catheter placement is another common presentation.10 Less frequently encountered manifestations include urinary tract infections, macrohaematuria, pain, difficult catheterisation and ejaculatory dysfunction.

It can be challenging to differentiate between benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a common cause of LUTS, and urethral strictures because they share many clinical features (Table 3). However, BPH tends to affect older men (ie typically >50 years of age). In contrast, a younger man (ie <40 years of age) presenting with poor urinary flow is more likely to have a urethral stricture. Also, men with BPH will report an improvement in urinary flow with straining. Conversely, men with a urethral stricture do not get an improvement in urinary flow by straining.

| Table 3. Clinical features of benign prostatic hyperplasia in comparison to urethral stricture |

| Characteristic |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

Urethral stricture |

| History |

- Tend to be older men (ie >50 years of age)

- Urinary flow improves with straining

|

- Tend to be younger men (ie <40 years of age)

- Urinary flow does not improve with straining

|

| Symptoms |

- Progressive symptoms of lower urinary tract obstruction

- Storage urinary symptoms – frequency, urgency, nocturia, incontinence

- Voiding urinary symptoms – slow stream, straining to void, intermittency during urination, hesitancy, terminal dribbling

- Storage urinary symptoms are often more bothersome than voiding symptoms

- Moderate-to-severe benign prostatic hyperplasia is associated with an increased incidence of acute urinary retention

|

- Progressive symptoms of lower urinary tract obstruction – especially hesitancy, a poor stream, terminal dribbling, a feeling of incomplete emptying

- Acute urinary retention is another common presentation

|

| Physical examination |

- Non-tender, enlarged prostate on digital rectal examination

|

- Small, non-enlarged prostate on digital rectal examination

- Stigmata of lichen sclerosus (Figure 2)

- Scars from previous surgery

|

| Investigations |

- Ultrasound demonstrates:

- enlarged prostate volume

- a thick-walled bladder before voiding

- post-void residual volume

- Low Qmax (maximum urinary flow rate) on uroflowmetry

|

- Haematuria and/or infection may be present on urinalysis

- Low Qmax and ‘plateau’ shape of flow curve on uroflowmetry

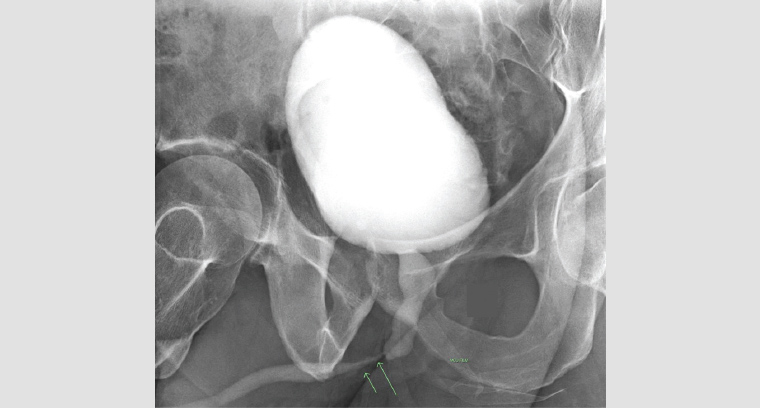

- Significant distension of the proximal urethra above level of the stricture on a urethrogram (Figure 3)

- Visualisation of a stricture via cystoscopy

|

Physical examination provides clues about the aetiology of urethral stricture disease. The patient must be adequately exposed to facilitate meticulous inspection of external genitalia. Any stigmata of lichen sclerosus or scars from previous surgeries should be carefully noted. Patients should also be examined for superficial infections, abscesses and epididymo-orchitis secondary to a urinary tract infection.

The American Urological Association (AUA) advises that clinicians use a combination of urinalysis, uroflowmetry and ultrasonography assessment of post-void residual bladder volume in the initial work-up of a suspected urethral stricture.11 If the GP suspects a urethral stricture is present, they can acquire these preliminary investigations while simultaneously referring onto a urology service. The urologist may subsequently arrange for a flexible cystoscopy and/or urethrography to establish the diagnosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A retrograde urethrogram demonstrating a mid-distal bulbar stricture

If untreated, urethral strictures can lead to significant complications including elevated post-void residual bladder volumes, a thick-walled trabeculated bladder, acute urinary retention, hydronephrosis, calculi formation, renal failure, urethral fistula and periurethral abscess.5,10 Indeed, Hoy et al reported that up to 16% of men with symptomatic urethral strictures develop complications while waiting for surgical intervention.12 Therefore, early detection and prompt referral to a urologist is essential for reducing morbidity and mortality from urethral strictures.

Management

The earliest recorded treatment of urethral strictures originates from Sushruta, the founder of Ayurveda medicine in India in the sixth century BC.13,14 Sushruta described how dilation could be achieved by passing a reed catheter into the urethra.13,14 In the nineteenth century, urethral dilation was refined by the development of bougies and balloon dilators.14 Today, urethral dilation is performed with filiforms and followers, balloons or coaxial dilators inserted over a guidewire.15 However, as recognised by Paget nearly two centuries ago,14 urethral dilation remains both tedious and non-curative. Following successful dilation, the patient must be compliant with intermittent self-dilation to maintain urethral patency. Understandably, self-dilation reduces the patient’s quality of life, thereby reducing their compliance and predisposing them to stricture recurrence.16

Today, treatment for urethral stricture disease is broadly divided into three classes: 1) minimally invasive endoscopic procedures, 2) surgical reconstruction of the urethra and 3) urinary diversion.

Minimally invasive endoscopic procedures

In an effort to find a cure for urethral strictures, physicians began developing internal and external urethrotomy techniques in the nineteenth century.14 Invention of the urethrotome produced optical urethrotomy, wherein a longitudinal cut is made in the stricture under direct vision, thereby widening the lumen. Optical urethrotomy is widely practised, but its long-term success is disputable. While Mundy et al reported that 50% of isolated short bulbar strictures were curable by optical urethrotomy,17 Santucci et al concluded the cure rate from optical urethrotomy was actually as low as 8%.18 Furthermore, 30–80% of men who have a urethrotomy will go on to develop a recurrent stricture.19,20 Such recurrences can lead to a chronic stricture state requiring repeated urethrotomies, which makes subsequent urethroplasty more difficult.4,21

Many urologists still offer urethrotomy as a first-line treatment; however, its success depends on stricture location, stricture length, number of strictures, amount of surrounding spongiofibrosis and number of previous urethrotomies.20,21 This is reflected in the current urethral stricture guideline published by the AUA, which states that surgeons may offer urethral dilation or endoscopic urethrotomy for the initial treatment of a short (<2 cm) bulbar urethral stricture.11

Surgical reconstruction

Urethroplasty is the open surgical reconstruction or replacement of a urethra that has been narrowed by scar tissue. Urethroplasty techniques include: 1) excision with primary anastomosis, 2) incision with onlay graft or flap repair and 3) stricture excision with an anastomosis that is augmented with a graft. Depending on the complexity of urethral stricture disease, reconstruction can be performed via a single- or multiple-stage approach. Ultimately, the chosen technique depends on stricture location and length as well as expertise of the urologist.

While urethroplasty is a challenging operation that requires reconstructive expertise, it is generally well tolerated with a high rate of success.22 Almost 11 years ago, Meeks et al reported that stricture recurrence rates post urethroplasty ranged from 8.3% to 18.7%.23 More recently, Robine et al performed a systematic review of MEDLINE literature from 2004 to 2015 wherein they found the success rate of anastomotic urethroplasty was 68.7–98.8% for strictures 1.0–3.5 cm and 60–96.9% for augmented urethroplasty performed for strictures 4.2–4.7 cm.24

Unsurprisingly, complications of urethroplasty are related to the location of stricture, length of stricture, surgical technique, type of substitution tissue, surgeon’s ability and patient selection.25 Commonly encountered problems include urine leak, urinary tract infections and wound complications.25 There is also potential for troublesome sexual side effects secondary to anastomotic ischaemia, stricture recurrence, erectile dysfunction and penile shortening.26 However, multiple studies evaluating patient-reported urethroplasty outcomes have concluded that most patients obtain a significant improvement in urinary symptoms and quality of life while maintaining erectile function.27–29

Despite the high success rates of urethroplasty, repetitive endoscopic procedures remain the most common treatment for urethral strictures in Australia. Nonetheless, over the past two decades, there has been a sizable reduction in endoscopic procedures and corresponding increase in urethroplasty in Australia.4 Specifically, from 1994 to 2016, the number of urethral dilation procedures performed across Australia decreased by 75%, and the number of urethrotomy or urethrostomy procedures decreased by 84%.4 During this period, the number of single-stage urethroplasty procedures increased by 144%.4

Urinary diversion

Urinary diversion is typically reserved for patients who have failed urethral reconstruction, declined urethral surgery or are unfit for surgery. Options for urinary diversion include suprapubic catheter placement, perineal urethrostomy and supravesical urinary diversion. Insertion of a suprapubic catheter is suitable for patients who are unfit or who wish to avoid surgery. If surgery is feasible, then perineal urethrostomy enables urination by diverting the distal bulbar urethra into the perineum. Alternatively, supra-vesical urinary diversion (eg ileal loop urinary diversion) is a treatment of last resort because of its significant morbidity and mortality.30

Conclusion

Urethral strictures are an ancient malady that still adversely affects many men today. Despite the recent emergence of urethroplasty as a highly successful treatment, urethral dilation and endoscopic procedures are still widely practised in Australia. However, by improving awareness of reconstructive options among GPs and urologists, more Australian men will have access to urethroplasty.