Approximately 65% of all cardiovascular disease (CVD)–related deaths in Australia occur in people with diabetes or pre-diabetes.1 The mortality rate in people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) almost doubles with the coexistence of CVD, resulting in an estimated 12-year reduction in life expectancy.2 Typically, people with T2D experience atherosclerotic CVD earlier and with greater severity than people without T2D.3

Despite their significantly elevated risk, suboptimal prescribing of blood pressure (BP)–lowering,4,5 lipid-modifying4–6 and antiplatelet therapy5 for patients with diabetes and CVD has been reported in Australian primary care. Australian data also show that many patients with diabetes and/or CVD do not meet guideline recommendations for prescribing,4–10 monitoring and treatment targets for managing cardiovascular risk.5,7

Blood glucose–lowering medicine (GLM) selection is also increasingly complex because of the increase in available medicines, and the focus on cardiovascular safety since the US Food and Drug Administration mandated in 2008 that all new studies must demonstrate cardiovascular safety.11 Several trials have shown not only cardiovascular safety, but also additional cardiovascular and renal benefits over placebo.12–20

The aim of this study was to investigate management of T2D and atherosclerotic CVD risk factors in general practice, using MedicineInsight data to explore medicines prescribed, monitoring performed and achievement of treatment targets. The study was part of a quality improvement program that ran from June 2018 to April 2019 and involved presenting practice-level data to general practitioners (GPs) at small group meetings to identify opportunities for improvement in clinical care.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted using MedicineInsight, a large national general practice database developed and managed by NPS MedicineWise, with funding support from the Australian Government Department of Health.21 MedicineInsight extracts longitudinal, de-identified patient health records including demographics, encounters, diagnoses, prescriptions and pathology tests from Best Practice and Medical Director clinical information systems in participating practices. In October 2018, MedicineInsight had recruited 662 practices across Australia, representing approximately 8.2% of all general practices in Australia and more than 2700 GPs.21 MedicineInsight has national coverage across all states and territories. Practices are recruited to MedicineInsight using non-random sampling. In comparison to national data, practices within Tasmania and inner/outer regional areas are over-represented and practices within South Australia and remote/very remote regions are under-represented.22 The characteristics of regular MedicineInsight patients are broadly comparable to patients who visited a GP in 2016–17 and 2017–18 in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) data, in terms of age, sex, Indigenous status and socioeconomic status.21,23

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) National Research and Evaluation Ethics Committee (NREEC) granted approval (NREEC 17-017) for the standard operation and use of the MedicineInsight program, under which this project was conducted.

Participants

Regular patients from general practices participating in the MedicineInsight program as at 1 November 2018, aged ≥18 years with diagnoses of both T2D (or unspecified diabetes) and atherosclerotic CVD (coronary heart disease, ischaemic stroke or peripheral vascular disease) were included in this study – hereafter referred to as ‘patients with T2D and CVD’. (Regular patients are defined as those who have at least three encounters with the practice in the past two years [preceding 1 November 2018], in accordance with the RACGP’s definition of ‘active’ patients.)

Further selection criteria for practices and patients are provided in Appendices 1 and 2.

Study outcomes

For patients with T2D and CVD, the researchers used information recorded in MedicineInsight to assess:

- the percentage of patients meeting Australian guideline recommendations for

- medicines indicated for reducing cardiovascular risk currently recorded in the clinical information system (ie BP-lowering, lipid-modifying and antiplatelet or anticoagulant medicines);24 note that some relevant medicines, such as aspirin, may be purchased over the counter (OTC); if these were recorded in the patient’s current medications list they were captured in this study

- monitoring of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and BP (3–6-monthly), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C; 12-monthly) based on Endocrinology Therapeutic Guidelines at the time25 (since this study, HbA1c and BP recommended monitoring frequency has increased to 3–4-monthly)26

- achievement of general treatment targets for HbA1c (≤53 mmol/mol [7%]),27 BP (<140/90 mmHg)27 and LDL-C (<1.8 mmol/L)28

- the number of GLM classes prescribed for patients, including for patients with different HbA1c levels

- the choice of add-on treatment for patients prescribed metformin-based combination treatment.

Assessment of these outcomes depends on medicines, tests and assessments having been recorded in the patient’s general practice record and in extractable fields. Further details are provided in the limitations section. Further details about included medicines can be found in Appendix 3. Monitoring recommendations and general treatment targets are summarised in Appendix 4.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to present study outcomes including proportions, means, medians and standard deviations (SD). Robust standard errors were used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for clustering by practice site. Missing data are presented as not recorded. Data analyses and management were conducted with SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (Cary, NC, USA, 2015).

Results

Of 1.8 million regular patients aged ≥18 years in the MedicineInsight database at 1 November 2018, 134,879 (7.6%; 95% CI: 7.3, 7.9) had T2D; of these patients, 33,559 (24.9%; 95% CI: 24.2, 25.5) also had CVD. Overall, 1.9% of regular patients had both T2D and CVD. Sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1. Characteristics of regular patients with both T2D and CVD in the MedicineInsight dataset (n = 33,559), 1 November 2018 |

| Age (years) |

|

|

| Age, mean (SD) |

73 (11.0) |

|

| Age, median (Q1–Q3) |

74 (66–81) |

|

| Gender |

n (%) |

95% confidence interval |

| Male |

21,250 (63.3) |

62.6, 64.0 |

| Female |

12,296 (36.6) |

36.0, 37.3 |

| Rurality |

| Major city |

18,756 (55.9) |

50.3, 61.5 |

| Inner regional |

9,540 (28.4) |

23.4, 33.4 |

| Outer regional |

4,531 (13.5) |

9.9, 17.2 |

| Remote |

464 (1.4) |

0.6, 2.1 |

| Very remote |

88 (0.3) |

0.1, 0.5 |

| State |

| Australian Capital Territory |

467 (1.4) |

0.2, 2.6 |

| New South Wales |

11,665 (34.8) |

29.3, 40.2 |

| Northern Territory |

301 (0.9) |

0.2, 1.6 |

| Queensland |

5,662 (16.9) |

12.8, 20.9 |

| South Australia |

762 (2.3) |

0.5, 4.0 |

| Tasmania |

2,998 (8.9) |

5.3, 12.5 |

| Victoria |

6,912 (20.6) |

15.8, 25.4 |

| Western Australia |

4,418 (13.2) |

8.9, 17.5 |

| Other territories |

1 (0.0) |

0.0, 0.0 |

| Socioeconomic status (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA]) |

| 1–2 most disadvantaged |

7,194 (21.4) |

17.6, 25.3 |

| 3–4 |

6,412 (19.1) |

15.9, 22.3 |

| 5–6 |

8,291 (24.7) |

20.8, 28.6 |

| 7–8 |

5,661 (16.9) |

14.3, 19.4 |

| 9–10 least disadvantaged |

5,778 (17.2) |

14.2, 20.3 |

| Smoking status |

| Smoker |

3,350 (10.0) |

9.4, 10.6 |

| Ex-smoker |

14,441 (43.0) |

42.2, 43.9 |

| Non-smoker |

13,980 (41.7) |

40.7, 42.7 |

| Not recorded |

1,788 (5.3) |

4.7, 5.9 |

| Comorbidities |

| Chronic kidney disease |

2,534 (7.6) |

6.5, 8.6 |

| Heart failure |

5,168 (15.4) |

14.7, 16.1 |

| Anxiety and/or depression |

11,776 (35.1) |

34.0, 36.2 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

5,508 (16.4) |

15.7, 17.2 |

| CVD, cardiovascular disease; T2D, type 2 diabetes |

Medicines for reducing cardiovascular risk and managing T2D

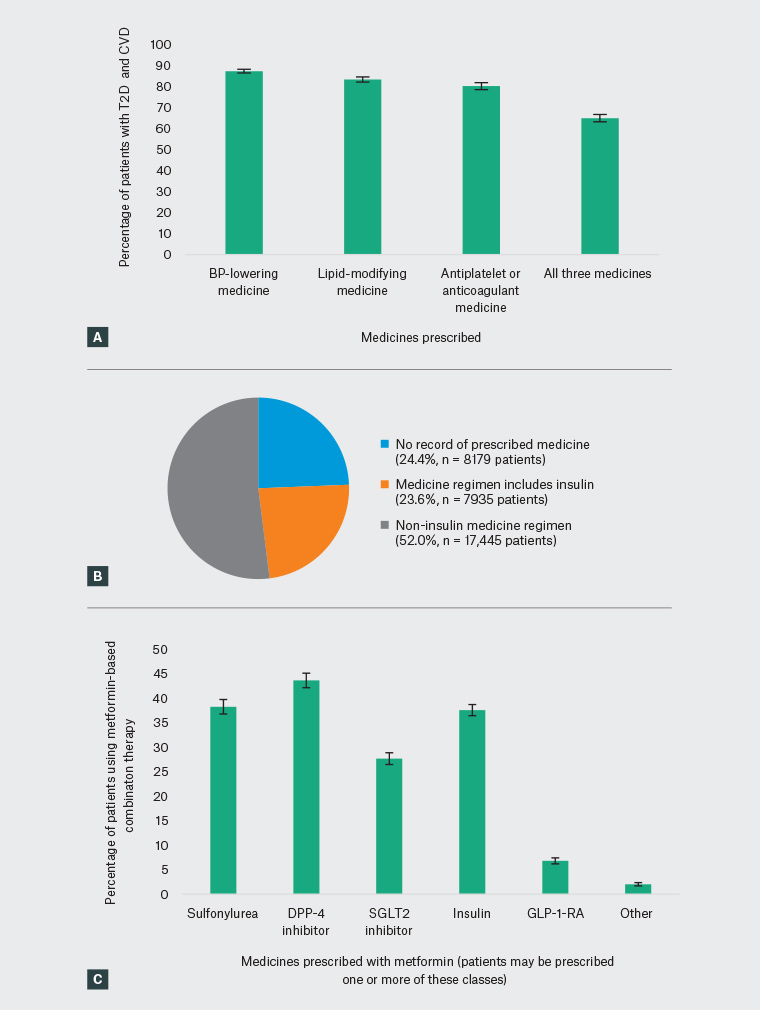

Among patients with T2D and CVD (Figure 1A, n = 33,559), there were records in the current medications list for BP-lowering medicines (87.4% of patients; 95% CI: 86.9, 87.9), lipid-modifying medicines (83.4%; 95% CI: 82.7, 84.1) and antiplatelet or anticoagulant medicines (80.2%; 95% CI: 79.3, 81.2). The researchers found records for all three recommended medicines for approximately two-thirds of patients (65.0%; 95% CI: 64.0, 66.0).

The researchers found records in the current medications list for insulin and/or non-insulin GLMs for 75.6% of patients (95% CI: 74.8, 76.4), and specifically a current prescription for insulin (with or without any other GLM) for 23.6% of patients (95% CI: 23.0, 24.3). This is shown in Figure 1B (n = 33,559).

Almost 40% of patients with T2D and CVD (Figure 1C, n = 12,839) had records of current prescriptions for metformin-based combination therapy. Among these patients, current prescriptions were found for a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor (43.6% of patients; 95% CI: 42.1, 45.1), a sulfonylurea (38.2%; 95% CI: 36.8, 39.7), insulin (37.5%; 95% CI: 36.4, 38.7), a sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (27.7%; 95% CI: 26.5, 28.9) and a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor antagonist (6.8%; 95% CI: 6.2, 7.4).

Figure 1. Current prescribing of medicines for patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease based on MedicineInsight data

A. Prescribing of medicines recommended to reduce cardiovascular risk for patients with T2D and CVD; B. Glucose-lowering therapy regimens prescribed for patients with T2D and CVD; C. Choice of metformin add-on treatment for patients with T2D and CVD

BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1-RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT2, sodium–glucose co-transporter-2; T2D, type 2 diabetes

Individual risk factor monitoring and achievement of cardiovascular and T2D targets

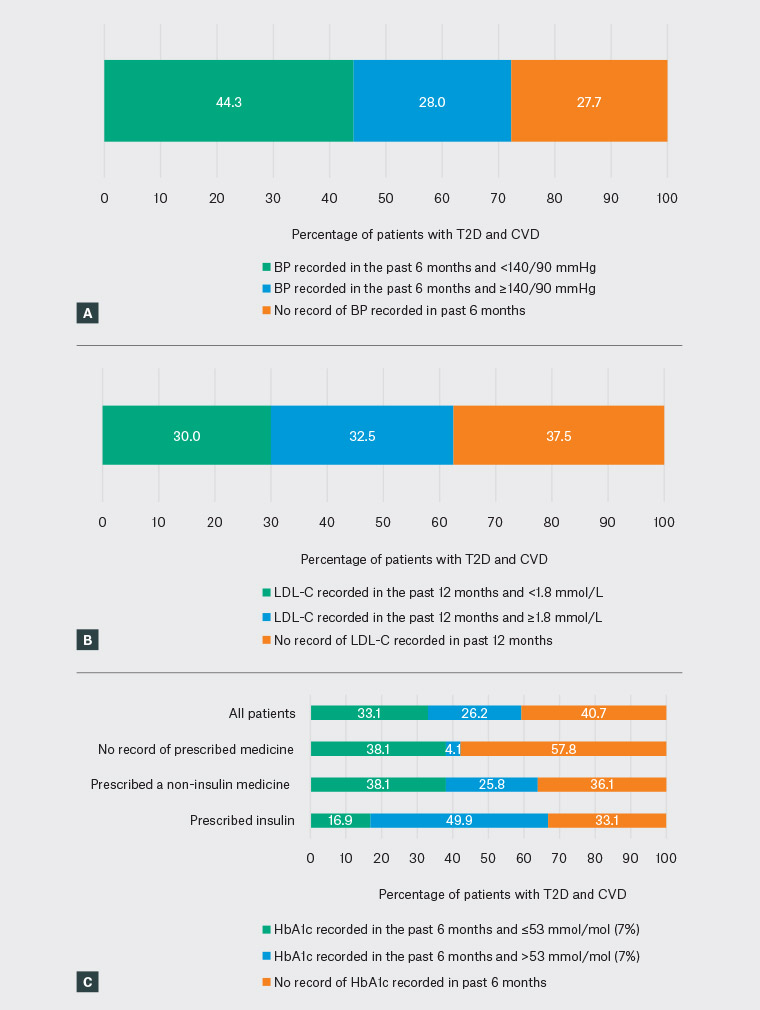

In fields available to MedicineInsight, the reseachers found records of patients with T2D and CVD having monitoring of their BP in the past six months (72.3% of patients; 95% CI: 70.7, 73.9), LDL-C in the past 12 months (62.5%; 95% CI: 60.8, 64.2), eGFR in the past 12 months (81.7; 95% CI: 80.2, 83.2) and HbA1c in the past six months (59.3%; 95% CI: 57.8, 60.8).

The researchers found records of patients with T2D and CVD achieving general guideline recommended targets for their BP based on measurements recorded in the past six months (44.3% of patients; 95% CI: 43.1, 45.4; Figure 2A), LDL-C based on measurements recorded in the past 12 months (30%; 95% CI: 29.0, 31.0; Figure 2B) and HbA1c based on measurements recorded in the past six months (33.1%; 95% CI: 32.1, 34.1; Figure 2C).

Achievement of the general guideline-recommended HbA1c target based on measurements recorded in the past six months was lower among patients with a current prescription for insulin than among patients with either no GLMs recorded in the current medications list, or those with current prescriptions recorded only for non-insulin GLMs (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Cardiovascular and diabetes risk factor monitoring and achievement of targets among patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (n = 33,559) based on MedicineInsight data

A. BP measurements recorded for patients with T2D and CVD; B. LDL-C measurements recorded for patients with T2D and CVD; C. HbA1c measurements, by treatment type, recorded for patients with T2D and CVD

BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; T2D, type 2 diabetes

Treating to target

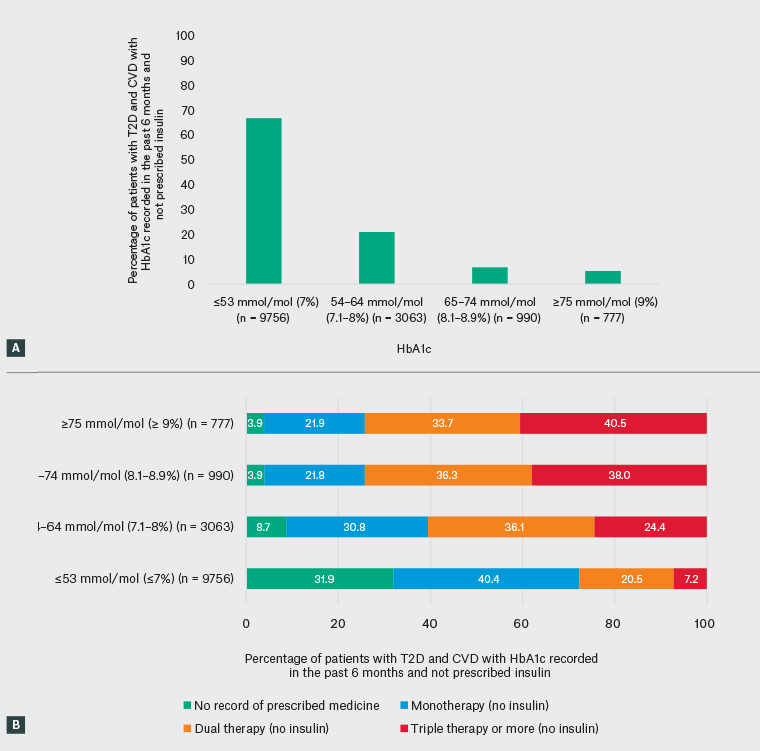

The researchers explored treating to target among patients with T2D and CVD who had a record of monitoring in the past six months and no record of insulin in their current medications list. Specifically, the researchers were looking at the number of different classes of GLMs prescribed for patients with different levels of HbA1c (Figure 3). Patients prescribed insulin were not included, as insulin treatment is more likely to be intensified, rather than adding an additional class of medicine.29

Of patients with T2D and CVD, 14,586 (56.0%) had recent monitoring and were not prescribed insulin. Of these patients, 66.9% achieved HbA1c ≤53 mmol/mol (7%), and 21.0% achieved HbA1c 54–64 mmol/mol (7.1–8%). This is shown in Figure 3A.

There appeared to be a direct relationship between the number of classes of GLMs prescribed and level of HbA1c (Figure 3B). However, almost 4% of patients with HbA1c ≥65 mmol/mol (8%) had no record of a GLM. Furthermore, 21.8% with HbA1c 65–74 mmol/mol (8.1–8.9%) and 21.9% with HbA1c ≥75 mmol/mol (9%) had a record of only a single currently prescribed medicine. Prescribing of dual and triple therapy or more was higher in those with HbA1c ≥65 mmol/mol (8%) than those with HbA1c <65 mmol/mol (8%). The percentage of patients with no record of a current GLM prescription was highest in those with HbA1c levels at target.

Figure 3. Achievement of general glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) target, and prescribing of blood glucose–lowering medicines by HbA1c level among patients monitored in line with guidelines and not prescribed insulin, based on MedicineInsight data (n = 14,586)

A. HbA1c measurements recorded in the past six months for patients not prescribed insulin; B. HbA1c measurements recorded, and the number of glucose-lowering medicines concurrently prescribed, for patients not prescribed insulin

BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; T2D, type 2 diabetes

Discussion

Few studies to date have investigated management of patients with both T2D and CVD. To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the largest Australian study to investigate management and treatment outcomes for these patients as recorded in general practice data. Overall, it was found that 1.9% of patients aged ≥18 years had both T2D and CVD, corresponding to approximately 380,000 adults in Australia. This would be an average of 10 such patients per GP (based on approximately 37,000 GPs in Australia).30

These findings indicate potential room for improvement in prescribing of recommended medicines, risk factor monitoring and achievement of general guideline-recommended targets. It is not possible to exclude the possibility that patients are receiving clinical care from other providers, which is not captured here, or that relevant data were recorded in fields inaccessible to MedicineInsight.

In line with a previous Australian study of patients with diabetes and CVD, it was found that one-third of patients did not have a record of all three guideline-recommended treatments for reduction of cardiovascular risk.5 Results seen in this study are also broadly similar to4,31 or higher6,8–10 than those seen in other Australian studies of patients with CVD (with or without diabetes). Any differences seen between this study and previous studies may reflect true differences, or be due to disparate study designs, sampling methodologies or definitions of T2D

and/or CVD.

BP-lowering and lipid-modifying medicines are known to reduce cardiovascular events in people with diabetes and CVD, regardless of pre-treatment levels.24 Optimising appropriate treatment could improve outcomes for these patients.

Among patients with T2D and CVD guideline-recommended individual risk factor monitoring for BP, LDL–C and HbA1c was not evident for 27.7%, 37.5% and 40.7% of patients, respectively. However, as noted, risk factor monitoring might have been performed in other care settings (eg in other practices or hospitals) and not captured here. Most patients in this study did not have evidence of recent BP, LDL-C or HbA1c measurements meeting general targets. The researchers are unaware of any other published studies reporting on rates of monitoring and achievement of CVD and diabetes targets for patients with both T2D and CVD.

Australian data show the difficulty of achieving HbA1c targets for patients with diabetes,4,5,32 although improvements have been made in recent years.32 The present data also highlight the challenge of achieving glycaemic targets, reflecting the progressive nature of the condition and the complexity of diabetes management.

The importance of glucose lowering to prevent long-term microvascular complications is well documented33 and intensification of treatment for patients not achieving HbA1c targets is a major tenet of the Australian Diabetes Society (ADS) recommendations.34 For the first time, the researchers present large-scale Australian primary care data showing specific glucose management of patients with T2D and CVD. The successful achievement of the HbA1c general target seen for some patients (especially those with evidence of guideline-recommended monitoring and not prescribed insulin), suggests treating to target may be occurring. The use of multiple medicines by many patients with HbA1c above the general target also supports this, and further highlights the challenges of getting many patients to target. In line with other Australian studies of patients with diabetes,4,5,32 and diabetes with CVD,5 this study shows potential room for improvement in medicine prescribing.

Choice of GLM is important for patients with both T2D and CVD. This study found that around 30% of patients prescribed metformin-based combination therapy were prescribed an SGLT2 inhibitor and less than 10% were prescribed a GLP-1 receptor antagonist. The percentage of patients prescribed metformin-based combination regimens that included a sulfonylurea, insulin or a DPP-4 inhibitor was much higher. At the time of data collection, these percentages correlated with stepwise prescribing choices as outlined in the ADS blood glucose management algorithm first published in 2016.34 International guidelines now highlight that medicines with proven CVD benefit (ie SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor antagonists) should be prioritised when adding to metformin35,36 (or even before metformin – although this conflicts with Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme [PBS] requirements).35 The ADS recently updated its management algorithm, and the RACGP recently updated its guidelines for management of T2D to include emerging evidence from cardiovascular outcomes trials.27,34

Strengths

The importance of high-quality patient records in general practice is increasingly recognised, with the data being used across the healthcare system by multiple practitioners and also for research, policy and education.37 Strengths of this analysis include the size and national coverage of the MedicineInsight dataset. Unlike other national prescribing datasets in Australia, these data contain diagnoses recorded in general practice. When compared with MBS data, characteristics of regular patients in the MedicineInsight dataset are broadly comparable to those who visited a GP in 2016–17 and 2017–18.21,23 Because MedicineInsight is an open cohort and patients in Australia can visit multiple general practices, the study included patients who had regular encounters with general practices, likely to be receiving most of their care at a MedicineInsight practice, to improve data quality.21 Prevalence estimates of several chronic conditions have been shown to be similar (eg CVD) or slightly higher (eg T2D) in the MedicineInsight population to those reported in other Australian sources.21–23 The proportion of those with T2D who had CVD in this study (24.9%) was similar to findings in another Australian study that reported on CVD in patients with diabetes (26%).5 A formal condition validation study comparing MedicineInsight data with a retrospective review of original electronic health records, supports the validity of the T2D algorithm used in this study, the findings of which will be published elsewhere soon. Previous studies have also found MedicineInsight data show qualitative agreement with external data sources.38 The use of clinical records reduces subjective biases found in self-reported health surveys, since these data comprise GP-identified diagnoses and documented medicines including those prescribed to patients. Also, MedicineInsight captures medicine subsidised by the PBS/Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS) and private prescriptions as well as other medicines (eg OTC medicines or those prescribed by others) that have been recorded by the GP into the clinical information system.

Limitations

These data have limitations in addition to those inherently associated with routinely collected data, described elsewhere.21 Data availability in MedicineInsight depends on whether diagnoses, medicines, tests or assessments have been recorded in the patient’s general practice record and whether they have been recorded in fields from which data can be extracted and analysed.21 For privacy reasons, MedicineInsight does not include data from progress notes, which may contain further clinical information, possibly resulting in missing data. Also, the absence of standardised definitions for conditions means that the present cohort may differ from other similar studies. A small proportion of patients with type 1 diabetes may have been misclassified as having T2D in this study if their only recorded diagnosis was ‘unspecified diabetes’. MedicineInsight does not capture whether patients have declined monitoring or treatment, or dispensed/used medicines prescribed. By limiting the cohort to regular patients, the reported prevalence of T2D and CVD may be higher when compared with other sources as a result of potential under-representation of younger or healthier Australians who may visit their GP less often and thus do not meet the regular patient criteria. The study may have underestimated the proportion of patients receiving optimal management if patients received management in other care settings (eg in other practices or hospitals) or if the patient’s current medication list was incomplete or if relevant information was recorded in non-extracted fields. Aspirin may be purchased OTC, hence this study may underestimate prescribing and/or recommendations for its use.

Practices in this study were not randomly selected; initial recruitment focused on practices with more than three GPs who were more likely to use electronic health records.21 Although not formally assessed, it may be assumed that MedicineInsight practices differ systematically from all practices in terms of being larger, more likely to use electronic health records and more interested in participating in quality improvement activities, which could bias results in either direction.

Implications for general practice

Achieving good outcomes for patients with diabetes and CVD requires a concerted effort to manage and monitor diabetes and associated comorbidities. This depends on cooperation between patients and practitioners, as well as having the right systems and structures. Guidelines exist to support evidence-based practice and to reduce patient complications, but this study highlights that many patients are potentially not being optimally managed in accordance with the guidelines, across a range of Australian general practices.

Facilitated practice visits using MedicineInsight data such as this quality improvement intervention may promote discussion among GPs at a practice level about their own practice and processes, as well as the barriers they face and enablers they may have implemented.

These data highlight the ongoing need to support general practice to identify practitioner, patient and health system solutions to help patients achieve evidence-based goals in this fast-moving environment.