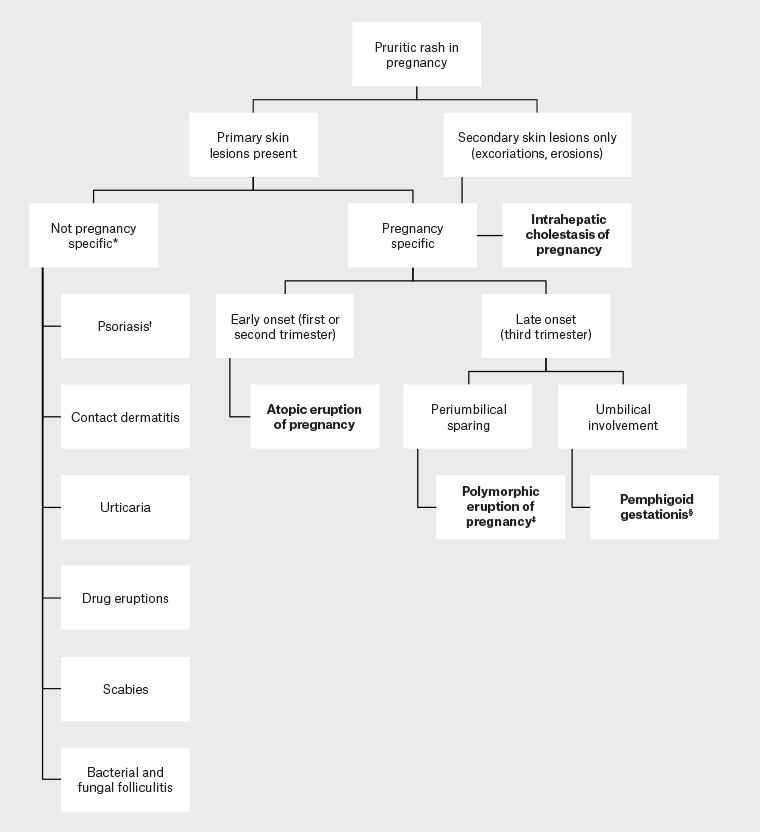

Pregnant women with itchy skin or a rash will often seek help from their general practitioners (GPs) initially. This article suggests a framework for the assessment of these presentations (Figure 1). While pre-existing skin conditions and non–pregnancy specific conditions such as psoriasis, urticaria, drug eruptions, contact dermatitis and scabies are important to consider, there is a specific group of conditions (called the specific dermatoses of pregnancy) that the clinician should consider when assessing a pregnant woman presenting with pruritus alone or a pruritic rash. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy are conditions that are pruritic and, by definition, only occur during pregnancy. These conditions have undergone reclassification into four main categories, namely polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pemphigoid gestationis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) and atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEP).1 Given clinicians are generally familiar with pre-existing conditions or cutaneous disorders affected by pregnancy while the specific dermatoses of pregnancy may be relatively more poorly understood, the specific dermatoses of pregnancy conditions are discussed in more detail in this article. Furthermore, potential fetal risks are emphasised to raise awareness among clinicians, which will assist with facilitation of timely management (Table 1). While ICP presents initially with intense itch that may be followed by skin manifestations due to scratching, ICP is included in discussion in this article as it is an important condition to consider when assessing any pregnant woman presenting with pruritus, given its associated potential fetal risks.

| Table 1. Summary of pregnancy-specific dermatoses |

| Pregnancy-specific dermatosis |

Clinical presentation |

Laboratory investigations |

Treatment |

Fetal risk |

| Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy |

Urticarial papules and plaques initially within abdominal striae and spreading to extremities; periumbilical sparing |

None |

Topical steroids, antihistamines, rarely systemic steroids |

None |

| Pemphigoid gestationis |

Vesiculobullous eruption starting on abdomen and spreading to extremities; periumbilical involvement |

Histopathology: subepidermal blister

Direct immunofluorescence: linear C3 deposition along basement membrane |

Systemic steroids |

Prematurity, SGA, stillbirth |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy |

No primary lesions; generalised pruritus involving palms and soles |

Elevated bile acid levels, mildly deranged LFTs |

Ursodeoxycholic acid |

Prematurity, fetal distress, stillbirth, FDIU |

| Atopic eruption of pregnancy |

Eczema in pregnancy: eczematous lesions on flexural surfaces, extremities, trunk

Prurigo of pregnancy: excoriated papules and nodules on extensor surfaces of limbs and trunk

Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy: papules on trunk before forming pustules |

Elevated IgE levels |

Emollients, topical steroids, antihistamines, UVB therapy |

None |

| C3, complement 3; FDIU, fetal death in utero; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LFTs, liver function tests; SGA, small-for-gestational-age; UVB, ultraviolet B |

Clinical assessment

Potential differential diagnoses to consider in a pregnant woman with pruritus and rash are included in Figure 1. The main dermatoses of pregnancy to exclude are pemphigoid gestationis and ICP given their associated fetal risks. Features that would support a diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis include an intensely itchy vesicular or bullous rash on the abdomen area with umbilical involvement, history of pemphigoid gestationis in previous pregnancies and presence of other autoimmune conditions. If pemphigoid gestationis is suspected, a biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. ICP is unique in that intense itch precedes any rash. Physical examination will reveal only secondary lesions due to scratching. If ICP is suspected, the diagnosis can be confirmed with elevated serum bile acid levels. Pemphigoid gestationis and ICP require timely specialist obstetric involvement, ideally within one week. Multidisciplinary team involvement is encouraged in approaching diagnosis and management of these conditions, involving the GP, dermatologist and obstetric team. The dermatoses of pregnancy are elaborated further in detail below.

Figure 1. A diagnostic framework to approaching rash and pruritus in pregnancy

*Included are suggested differential diagnoses to consider; however, this is not an exhaustive list.

†It is important to specifically consider pustular psoriasis of pregnancy given its maternal and fetal risks.

‡Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy tends to occur mostly in primigravid women. In multigravid women, consider other causes.

§Pemphigoid gestationis usually presents in the third trimester but can occasionally present earlier.

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy

PEP, or pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPP), occurs most commonly in primigravid women in the third trimester of pregnancy but uncommonly can present after delivery.1,2 It is relatively common and affects approximately one in 200 pregnancies.3 It has been suggested that the pathological basis of PEP is related to an inflammatory process triggered by rapid abdominal distension, which could explain the association of PEP with excessive maternal weight gain and multiple pregnancies.2,4

PEP presents with intensely pruritic urticarial papules before coalescing to form plaques (Figure 2). It initially starts on the abdominal wall within striae and spreads to the extremities, but the face, palms and soles are rarely involved. The periumbilical area is classically spared.2 PEP is a clinical diagnosis, and skin biopsy is rarely required. Some patients can develop vesicles and targetoid lesions, which can be difficult to distinguish from pemphigoid gestationis. In such cases, a biopsy should be performed for histology and direct immunofluorescence studies. As opposed to pemphigoid gestationis, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in PEP.5 Direct immunofluorescence is used for demonstration of tissue-bound antibody and complement, and it can be requested with histology after taking a biopsy of the edge of the vesicle. The specimen for direct immunofluorescence should be placed in saline or a special immunofluorescence medium (not formalin).

Figure 2. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: pruritic papules on the abdominal area coalescing to form plaques, with periumbilical sparing

PEP is self-limiting and tends to resolve spontaneously 4–6 weeks after its onset, or days to weeks after delivery.2,6 It does not have any adverse effects on the fetus and does not tend to recur in subsequent pregnancies.4,7 Treatment is aimed at symptom relief with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines. In more severe cases, systemic corticosteroids can be used. Prednisolone at a dose of 40–60 mg daily (tapering over a few days) is the systemic steroid of choice and is generally considered safe in pregnancy, especially as only short-term therapy is usually required to achieve control.5 There have been rare reports of severe intractable PEP prompting early delivery;8,9 however, this is rarely required, and controversy remains regarding the true effect of delivery on resolution of symptoms.2,10

Pemphigoid gestationis

It is important to distinguish the self-limiting PEP from pemphigoid gestationis, previously known as herpes gestationis, because of the potential fetal risks associated with pemphigoid gestationis. Pemphigoid gestationis is an autoimmune blistering disease of pregnancy that has been associated with other autoimmune conditions such as Grave’s disease, vitiligo and pernicious anaemia.11 It most commonly begins in late pregnancy but, unlike PEP, may occur earlier. It resolves within a few weeks after delivery.12 It tends to recur in subsequent pregnancies and can relapse with menstruation and oral contraceptive use.4,13 Although well described, pemphigoid gestationis is rare, affecting approximately one in 50,000 pregnancies.14

Pemphigoid gestationis presents with papules, plaques, vesicles and bullae that first appear on the abdominal wall and spread to the extremities. The lesions are intensely pruritic. Unlike PEP, the umbilical area is involved (Figure 3). The face and mucous membranes are rarely involved.

12,15 The diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis is confirmed by histopathology and, most importantly, direct immunofluorescence studies, which show linear deposits of complement 3 +/– immunoglobulin (Ig) G along the basement membrane.

11,16

Figure 3. Pemphigoid gestationis: plaques and vesicles that begin on the abdominal wall before spreading, with periumbilical involvement

Pemphigoid gestationis is associated with prematurity, small-for-gestational-age infants and stillbirth.17 Close antenatal surveillance and fetal monitoring are recommended for pregnant women with pemphigoid gestationis. Treatment is aimed at managing pruritus and preventing further formation of blisters.5 In mild cases, topical corticosteroids can be used; however, systemic steroids, such as prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day, are usually considered first-line therapy.13 Multidisciplinary care, including dermatology input, should be considered for patients with suspected pemphigoid gestationis, especially in patients with refractory pemphigoid gestationis.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

ICP is the only dermatosis of pregnancy that presents initially with pruritus without any primary skin lesions. Skin manifestations, such as excoriations, erosions and prurigo nodules, result from scratching due to severe pruritus. It is crucial to recognise ICP as it can be associated with poor fetal outcomes. Although the prevalence of ICP varies worldwide (between 0.3% and 5.6% of pregnancies) depending on geographical and ethnic factors, an Australian study has shown a prevalence of 0.7%.18

ICP usually presents in the second or third trimester with sudden-onset pruritus all over the body, including the palms and soles. The pruritus tends to resolve postpartum; however, it can recur in subsequent pregnancies.19,20 The diagnosis is based on the combination of severe pruritus and laboratory investigations, which will show elevated bile acid levels.21 While alkaline phosphatase levels are normally elevated in pregnant women, liver function tests may also show mildly abnormal aspartate and alanine transaminase levels.19 The mainstay of treatment for ICP is ursodeoxycholic acid, a naturally occurring bile acid given at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day or 1 g/day orally to manage pruritus, reduce bile acid levels and improve fetal outcomes.22,23

ICP is associated with pregnancy risks such as prematurity, fetal distress and stillbirth.24 Fetal death predominantly occurs around 38 weeks of gestation; therefore, it is usually recommended that delivery occurs by 38 weeks.25 In severe cases, earlier delivery may be indicated.26 ICP is often closely managed with maternal fetal medicine specialists.

Atopic eruption of pregnancy

AEP is a term coined to define a group of conditions that includes eczema in pregnancy, prurigo of pregnancy and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy (PFP).1 However, the recent inclusion of prurigo of pregnancy and PFP under AEP is controversial as they have not been conclusively shown to have an atopic diathesis.26 They share similarities of presenting with itchy eczematous lesions with a benign prognosis with no maternal or fetal risks.1,5 In contrast to the other dermatoses of pregnancy, AEP tends to present earlier in pregnancy, in the first or second trimester.1

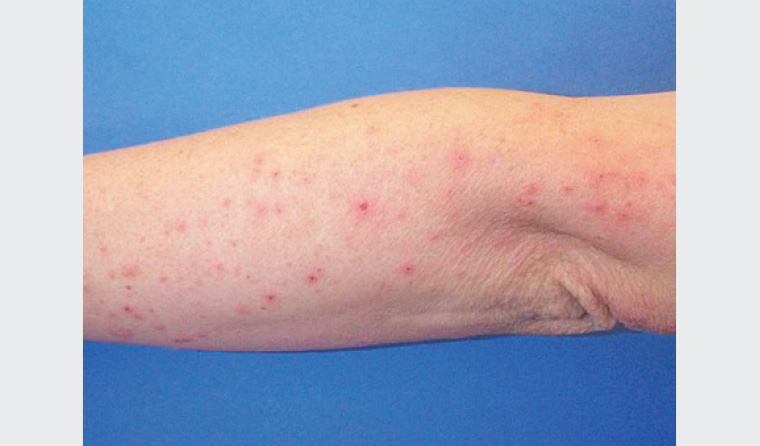

Eczema in pregnancy is the most common dermatosis of pregnancy, affecting almost 50% of patients who present with dermatoses of pregnancy. A woman with eczema in pregnancy may present with either eczematous skin changes for the first time if they are a patient with an atopic background or, less commonly, with exacerbation of pre-existing atopic dermatitis. Sites involved include classic flexural surfaces as well as the extremities and trunk.1 Prurigo of pregnancy affects approximately one in 300 pregnancies.4 The characteristic lesions of prurigo of pregnancy are erythematous excoriated papules or nodules on the trunk and extensor surfaces of the arms and legs (Figure 4). The lesions can sometimes resemble prurigo nodules.1,27 ICP should be considered as a differential diagnosis; however, in contrast to prurigo of pregnancy, pruritus precedes any rash in ICP. PFP is rare and affects one in 3000 pregnancies.28 It presents initially with papules on the trunk that evolve to form generalised pustules and follicular papules.26 Culture studies should be performed to exclude bacterial or fungal folliculitis.

Figure 4. Prurigo of pregnancy: excoriated papules on the extensor surface of the arm

The diagnosis of AEP is largely clinical, as there are no diagnostic tests. Histopathology is non-specific, and direct immunofluorescence studies are negative; however, serum IgE levels may be raised.1 AEP tends to resolve early in the postpartum period. Treatment of AEP is symptomatic with the use of emollients, topical corticosteroids and antihistamines. In severe refractory cases, a short course of systemic corticosteroids or narrow-band ultraviolet B therapy can be used.29

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), or impetigo herpetiformis, is considered a variant of generalised pustular psoriasis rather than a specific dermatosis of pregnancy.30,31 However, PPP merits special mention to encourage clinicians to consider this condition given its maternal and fetal risks. PPP is rare, and its prevalence is unknown because of the paucity of reported cases.

PPP typically presents in the third trimester of pregnancy and can recur in subsequent pregnancies.32 It is characterised by multiple sterile pustules in a circinate pattern, usually starting in the intertriginous areas and spreading centrifugally. As opposed to the other dermatoses of pregnancy, it is associated with systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, vomiting and diarrhea.33 Laboratory tests show neutrophilia, elevated inflammatory markers, hypocalcaemia, hypoparathyroidism, low phosphate and low vitamin D levels. Blood cultures and cultures of pustules are negative.34 Histopathology demonstrates spongiform pustules with neutrophils, psoriasiform hyperplasia and parakeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative.33 First-line treatment options include systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, infliximab, topical corticosteroids and topical calcipotriol.35 With early recognition and treatment, maternal risks such as delirium and tetany secondary to hypocalcemia can be avoided. Fetal prognosis is less favourable, with poor outcomes reported including intrauterine growth restriction and stillbirth.36

Conclusion

In summary, an awareness of pregnancy-specific dermatoses will assist the GP in the clinical approach to a pregnant woman presenting with pruritus and rash. Importantly, pemphigoid gestationis and ICP are diagnoses that should not be missed because of the potential adverse fetal outcomes. It is common for pemphigoid gestationis and ICP to be managed in conjunction with specialist dermatology and obstetric or maternal fetal medicine teams to optimise fetal outcomes. Although not specifically a dermatosis of pregnancy, PPP should also be considered given its potential maternal and fetal risks.