Background

Dental problems are common in general practice and are responsible for many avoidable hospitalisations. Medicine and dentistry are often practised in isolation, with little shared language or understanding.

Objective

The aim of this article is to help general practitioners (GPs) maximise effective dental referral strategies by briefly outlining basic dental nomenclature and describing the roles of different types of oral healthcare providers.

Discussion

The oral cavity contains hard and soft tissues that are all prone to oral disease, which can lead to systemic disease. It is important for GPs to have some basic familiarity with dental nomenclature, anatomy and tooth eruption times. In Australia, there are seven different oral healthcare providers and 13 dental specialities. This article will summarise their distinct roles and explain some common dental procedures used to definitively treat oral health problems. This knowledge should encourage more efficient interprofessional communication and enable general practitioners to optimise referral pathways for patients with oral health problems.

Oral and medical health are intimately linked, yet the two professions generally work separately.1 Patients often access care from general practitioners (GPs) for dental issues, with many avoidable hospitalisations for medical conditions of dental origin.2 Very few GPs have received any oral health education.3,4

The current authors have noted the separate training, funding, regulatory and administrative systems of the two professions, the many connections between oral and systemic health, and the importance of putting ‘the mouth back in the body’.1

There are numerous types of oral health practitioners to whom GPs can direct referrals. The maldistribution of dental practitioners across Australia means that many communities do not have a resident dental practitioner and must travel or rely on fly-in, fly-out or mobile dental services. Education in oral health literacy is key, and timely referral to dental practitioners may provide better patient outcomes with fewer potentially preventable hospitalisations.

In order to more effectively manage dental problems, it is important that GPs understand the language of dentistry. This article briefly describes basic dental nomenclature and anatomy and the roles of different types of oral healthcare providers and dental specialists. It illustrates some of the common definitive dental treatments that dental practitioners provide for common oral health problems. This understanding will enable GPs to make appropriate referral pathway decisions.

Dental nomenclature and dental anatomy

It is beneficial for GPs to have a basic understanding of dental nomenclature and dental anatomy to allow more effective interprofessional communication.

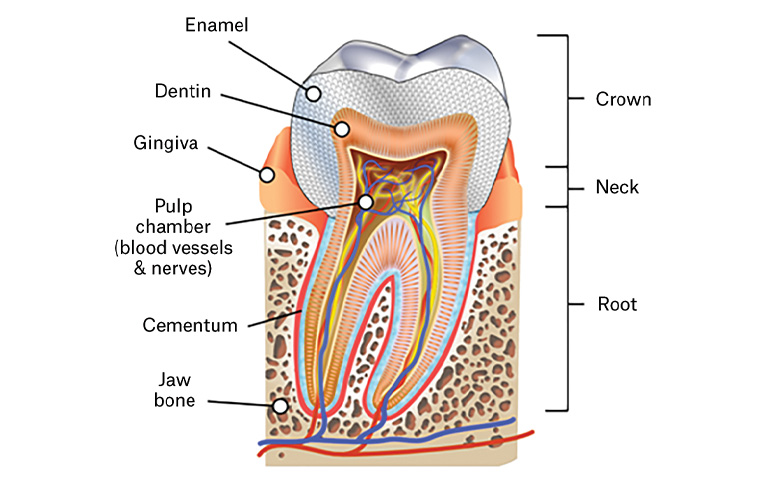

Basic dental anatomy (Figure 1) includes knowledge of both oral soft tissue structures and their nerve supplies, as well as hard tissues including enamel, dentine, cementum, alveolar bone and the periodontal ligaments that attach the tooth to the bone.5–7

Figure 1. Tooth structure

Human tooth diagram-en.svg by KD Schroeder, reproduced from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

The tooth numbering system used in Australia uses two numbers to describe the location of the tooth. The first number designates the quadrant, which progress clockwise from 1 to 4 in adult teeth, starting with the upper right. The second number describes the type of tooth from 1 to 8, with 1 being the central incisor, progressing backwards to 8, the wisdom tooth. Adults have 32 teeth, which begin eruption at six years of age. Wisdom teeth erupt between the ages of 17 and 21 years.7 Deciduous teeth similarly have quadrants designated 5–8 from the upper right and progressing clockwise. The teeth are identified from the baby central incisor (1) to the second baby molar tooth (5). The 20 baby teeth begin to erupt at 6–12 months of age and are fully erupted between 30 and 36 months of age.6

Dental workforce

The Australian oral health workforce includes dental practitioners (dentists) and six other oral healthcare providers (Table 1).8 GPs will mostly refer dental issues to dentists. GPs’ understanding of the interconnectivity between oral and medical health guides the referral pathway to the appropriate oral healthcare provider. Periodontal disease, for example, has been implicated in the development of various systemic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, preterm delivery of low-birthweight babies, diabetes, respiratory diseases, osteoporosis, renal failure and stroke.9 GPs often need to communicate directly with oral health providers about many interrelated medical and dental issues. Osteonecrosis of the jaw, for example, may be a consequence of failing to ensure that all essential dental treatments are completed before commencement of bisphosphonate medications used for osteoporosis or breast cancer.10 Xerostomia caused by commonly prescribed medications, diabetes, chemotherapy and therapeutic radiation to the head and neck can have enormous implications for both oral and medical health.11 The patient whose denture is not fitting properly, or is broken, may be unable to eat properly and consequently may have poor diet control in diabetes. The elderly patient who fails to thrive may have an undiagnosed oral cancer that causes pain under their denture, or a dry mouth due to prescribed medications. An appropriate oral healthcare referral from the GP is essential for better patient outcomes.

| Table 1. Oral healthcare workforce |

| Dentists* |

Tertiary-qualified dental practitioners who lead the dental team and provide all oral healthcare services to adults and children. They may pursue specialist training (Box 1). |

| Dental hygienists* |

Provide oral health assessment for oral diseases involving the periodontal (gum) health and provide treatments and education for the prevention of oral disease in people of all ages. |

| Dental therapists* |

Provide treatment, management and preventive services for people under 18 years of age. Their scope of work includes restorative and fillings treatment, tooth removal, additional oral care and oral health promotion. |

| Oral health therapists |

Tertiary-qualified practitioners who combine dental therapists’ oral healthcare – including restorative treatment and extractions – for people under 18 years of age, with dental hygienists’ preventive oral care for all ages. |

| Dental technicians |

Make and repair dentures (full and partial) and other dental appliances on referral from dentists. |

| Dental prosthetists* |

Dental technicians with further training to enable them to work directly with patients to construct and maintain removable prosthetic appliances or dentures. |

| Dental assistants/dental nurses |

Prepare patients for dental examinations and assist dentists and other dental care providers in providing oral healthcare. |

| *Practitioners registered with the Dental Board of Australia16 |

Scope of practice is contentious. Proponents support the use of oral health therapists in providing equitable access to oral healthcare, arguing mid-level oral healthcare providers are analogous to nurse practitioners in medicine who can provide high-level medical services without direct supervision from a medical practitioner.12 The Dental Board’s Scope of registration practice standard identifies that oral healthcare providers such as dental hygienists, dental therapists and oral health therapists can only perform procedures for which they are formally educated.13

Dental workforce distribution

Australia has a maldistribution of dental practitioners, with proportionally three times as many dentists practising in major centres when compared with rural and remote areas.14,15

As with medicine, there has been a growth of training institutions in recent decades, mainly in non-metropolitan locations. While the hope is that regional training leads to better rural/remote supply,16 the workforce impact is yet to be felt, with concerns expressed about an oversupply of dentists in Australia.17

As noted, there is a debate about addressing workforce maldistribution via appropriately trained mid-level dental providers in underserved areas.18 Unlike medicine, the vast majority of dental professionals work in private practice (84% of dentists and 66.5% of oral health therapists).19,20

Types of dental specialists

A dental specialist is a registered dental practitioner who has completed a minimum two years of general dental practice and the required speciality postgraduate study.21 The 13 dental specialties recognised in Australia are listed in Box 1. While GPs may refer direct to these specialists, the most common referral pathway is via the patient’s dentist. Specialists that patients will commonly be referred to include:

- endodontists – treat diseases of the human tooth primarily involving the dental pulp, root and root tissues

- oral and maxillofacial surgeons – provide procedures including extraction of problematic wisdom teeth, jaw repositioning and reconstructive surgery after facial trauma

- orthodontists – diagnose and correct alignment problems in growing and mature teeth and jaws; treat malocclusion for overlapping and overcrowded teeth and the accompanying alterations in the adjacent structures

- periodontists – deal with prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the diseases affecting the soft tissue and bone supporting the teeth and their replacements

- prosthodontists – restore and replace teeth using procedures such as crowns, bridges, dentures and dental implants

- specialists in special needs dentistry – care for patients with physical, medical or psychiatric conditions including intellectual disabilities, and provide specially tailored corrective and preventive dental treatment.

| Box 1. Dental specialists recognised in Australia and numbers employed in 201620 |

- Dental–maxillofacial radiologist (9)

- Endodontist (152)

- Oral and maxillofacial surgeon (159)

- Forensic odontologist (22)

- Oral surgeon (26)

- Oral medicine specialist (29)

- Oral and maxillofacial pathologist (5)

- Orthodontist (529)

- Paediatric dentist (119)

- Periodontist (201)

- Prosthodontist (191)

- Public health dentist (11)

- Specialist in special needs dentistry (12)

|

Common dental procedures

Understanding the solutions dental practitioners can offer for common oral health problems will enable GPs to refer patients more effectively. It is important that dentists and GPs both strive to improve patients’ oral health literacy, because the mouth is not separate from the rest of the body.

Appropriate referrals will limit the number of patients returning with dental issues that remain untreated and consequently escalate into conditions of medical significance.

Common definitive solutions to dental problems include the following:

- Composite bonding – used to repair teeth that are decayed, chipped, fractured or discoloured or to reduce gaps between teeth. Several layers of appropriately coloured resin are applied to the tooth, and each layer is hardened using an ultraviolet light. The final restoration is shaped and polished to mimic natural tooth structure.

- Crowns – fit over a tooth that is fractured, misshaped or damaged by caries. The dentist shapes the tooth, takes an impression and constructs the crown from porcelain, metal or porcelain bonded to metal.

- Veneers – are strong, thin pieces of porcelain that are bonded to the teeth. They are used to repair stained, chipped or decayed teeth and may help in closing gaps between teeth.

- Bridges or implants – replace missing teeth. The bridge uses artificial teeth that are anchored to adjacent natural teeth using crowns. Dental implants are titanium screws that are embedded into the bone and then have a crown placed over them to reproduce the appearance of a normal tooth.

- Extractions – are performed when teeth are severely damaged and unrestorable or when required for orthodontic treatment.

- Dentures – are removable prosthetic devices that replace lost teeth. Dentures that replace only a few teeth are called partial dentures; full dentures are often referred to as ‘false teeth’.

- Dental fillings – use several types of restorative materials to repair teeth that have been compromised because of cavities or trauma.

- Orthodontic braces – devices used to exert steady gentle pressure on the teeth to correct their alignment. These may be fixed or removable.

- Periodontal/gum surgery – may be required for periodontal disease, an infection affecting the gums and jaw bones, which can lead to loss of bony support, gums and teeth. Gingivitis is the milder and reversible form of gum disease but may progress to periodontal disease, which is associated with many health problems, including cardiovascular diseases, preterm delivery and other systemic illnesses.22

- Root canal therapy – treats diseased or abscessed teeth instead of extracting them. The tooth is opened, and infected tissue is removed from the centre of the tooth. This space is sterilised and, after several appointments to ensure complete removal of necrotic tissue, the tooth is filled and the opening sealed. Keeping the tooth helps to prevent the other teeth from drifting out of line and causing jaw problems. Saving a natural tooth avoids having to replace it with an artificial tooth via an implant, a bridge or a denture.

- Fissure sealants – are usually applied to the chewing surface of teeth and act as a barrier against decay-causing bacteria. Sealants are applied most commonly to the back teeth (premolars and molars).

- Teeth whitening – may include in-office or at-home bleaching. Teeth naturally darken with age; however, staining may be caused by substances such as coffee, tea, red wine, berries, tetracycline, as well as smoking or trauma.

Conclusion

An appreciation of the interconnectivity between medical and dental conditions will help GPs to recognise the importance of timely oral healthcare referrals to benefit their patients. Understanding the scopes of practice and treatments offered by different types of oral healthcare providers will enable GPs to better utilise those practitioners who might be available in their communities. Breaking down the barriers between medical and dental practitioners must begin with a shared understanding of the different roles of oral healthcare service providers in Australia today, and a common language.