Good morning, I am Doctor Butel. How can I help you?

This is the routine opening of my remote consultation for a person from the ‘bush’, which may be just out of town, a remote station, an island or an offshore fishing boat. Telehealth consultations are primarily a patient history–centric consult. The interaction has some essential underlying elements, which, although obvious, need to be considered.

The person on the other end of the line has a problem for which they require a general practitioner’s (GP’s) expertise.They are aware that the practitioner is not physically present. They want and need a practitioner’s help and the telehealth interaction is better than the patient’s current situation. Patients are generally aware of the limitations of the consultations.

I am a Northern Queensland Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) doctor who, along with my other remote primary health providers, must provide telehealth remote consultations to patients in the ‘bush’. These telehealth consultations are a component of the RFDS Program supported by the Australian Federal Government Department of Health. I have been working in this role for approximately five years. This article contains my reflections on the remote telehealth primary care process, particularly related to the RFDS context.

The Mt Isa RFDS base alone conducts >5000 telehealth telephone- and video-based consultations per year, the vast majority of which are primary care in scope. These consultations are carried out on Queensland Health services Telehealth Portal, via telephones (landline/satellite/mobile) or via video platforms such as Skype or Facetime. The Queensland section of the RFDS has been reported to provide more than 30,000 telehealth consultations per year to those in the remote areas of Queensland and Northern Territory.1,2

These consultations are usually for conditions that are the ‘bread and butter’ of primary care (Table 1). As such, these consultations do not take longer than an average consult in terms of time allocations once the practitioner is familiar and practised with this new medium. The telehealth consult can be as clinically satisfying as the traditional face-to-face primary care consult but is obviously being delivered via a different communication medium.3 There are guidelines available for primary care in Australia to assist with this process.4–8

| Table 1. Mt Isa Royal Flying Doctor Service: Telehealth consultations undertaken in the past 12 months* |

| Top five telehealth conditions |

International classification of diseases coding categories |

Percentage of annual telehealth consultations |

| 1 |

Conditions related to injury/accident |

14% |

| 2 |

Skin and subcutaneous conditions |

13% |

| 3 |

Respiratory conditions |

13% |

| 4 |

Gastrointestinal conditions |

12% |

| 5 |

Issues related to health status |

8% |

| *Data sourced from internal Royal Flying Doctor Service Queensland with permission |

Occasionally a complex consult does occur; in these events, the response is to realise the limits of the consult and work within those limits, if possible. If the patient requires referral as a standard of care, that needs to be arranged (eg arrange a physical clinic review, call the emergency service or arrange a presentation to the local hospital).

The telehealth consult can increase in complexity as it progresses. It is influenced by the interplay of the patient, the ‘reason(s) for the consult’, the clinician and practice factors.

For the clinician, who is a major party in the consult process along with the patient, it is fundamental to acknowledge clinician-based limits of acumen and knowledge in this restricted consult setting.

As the complexity increases dynamically within the consult, there will be a threshold at which it is ideal to consider a second opinion or different modality of care delivery. It is beneficial to reflect on threshold triggers prior to embarking on the telehealth consult process. As an example, here are some of my triggers:

- Communication triggers

- The patient is not engaging in the telehealth consult.

- There is a failure to meet the patient’s expectations.

- There is a sociocultural disconnect affecting communication.

- Clinical triggers

- There is a need for physical examination to support the consult.

- There are red flag symptoms elicited within the consult.9

- There is unacceptable diagnostic uncertainty.

- There is management uncertainty.

- There is a need for an escalation or urgency in clinical care.

- Operational triggers

- The time frame of the consult is significantly being exceeded.

- There are technical communication issues.

The complex consult will result in increased time utilisation, both within the patient consult and post-consult phases. There is often a need to source collateral information from other sources (observing the usual clinical privacy aspects). Further progress consultations may be needed as the patient’s clinical issues are identified, managed and refined. This is where the development of complex care plans can be implemented.

The telehealth consultation

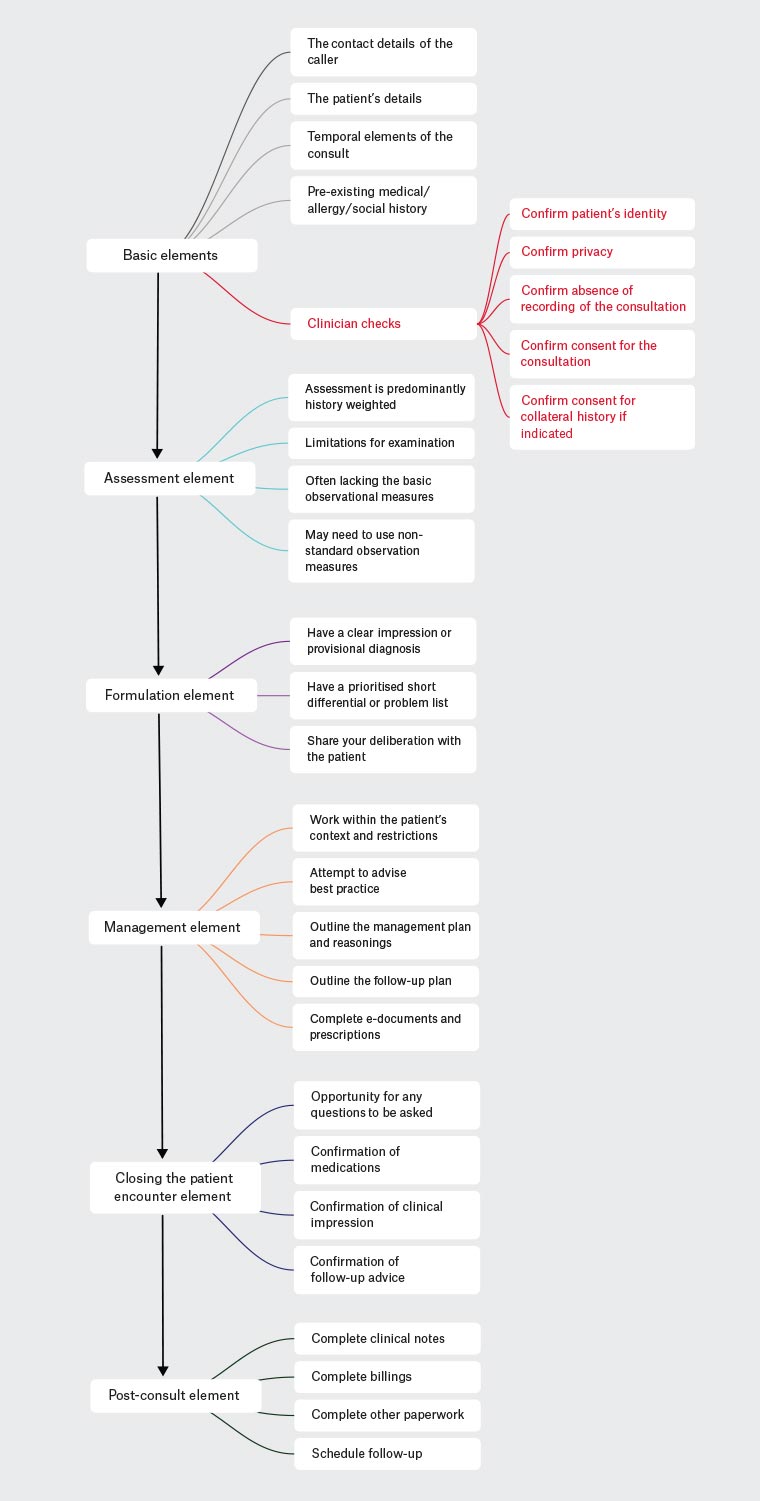

The crucial elements in a consult are shown in Figure 1. Many of these elements will already be in the practice software from prior encounters or can be pre-loaded by the practice receptionist at the time of initiation of the consult encounter.

Figure 1. Elements of the telehealth consultation flow

The basic elements

1. The contact details of the caller

- Who the caller is; this may not be the actual patient

- The caller’s name and relationship to the patient

- A correct contact telephone number of the caller (very important)

2. The patient particulars

- Name

- Date of birth

- Patient sex

- Patient ethnicity

- Any other demographics

3. The temporal consultation elements

- Time of consult

- Date of consult

4. Essential medical history elements (if the patient is not known to the practitioner or the practice)

- Medical history

- Surgical/obstetric history

- Mental health diagnostic history

- Medications

- Allergies

- Family history

Many of the above elements are standard work practice components of any consultation process.

When initiating the clinical telehealth consult, it is essential for the clinician to confirm:

- the identity and presence of the patient who is the subject of the consult

- the ability to have suitable privacy for this consult

- consent to proceed with the telehealth consult process

- that the consult is not being recorded

- consent from the patient to contact other parties if a collateral history is needed.

Assessment element

During the assessment stage, the GP can leverage their pre-existing expertise in patient assessment. Generally the patient has a diagnosis that needs to be identified, refined and framed by the presenting complaint and the practitioner’s careful inquiry. This is something at which primary care specialists are experts. The GP listens to the patient’s history, asks questions and formulates the differential with the provisional working diagnosis.

The old medical school adage, that more than 90% of the diagnosis is in the history, applies here. The remaining 10% is contributed by examination and investigation, which generally aid with refining the differential diagnosis and directing management.

The basic observations, such as temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, blood sugar and saturations, would ideally be available. However, these observations are often unavailable, and this uncertainty must be acknowledged and factored into the formulation.

Novel non-standard observations or tools can be used in remote locations. The caller may have access to tools such as a blood sugar monitor, automated home blood pressure monitor and/or thermometer.

It is important to remember that many patients have smartphones and smartwatches. These can provide static and dynamic visual and auditory information (eg clinical videos or photos of rashes, injuries), and they may contain historical health data (eg weight, cycle information, home blood pressure and heart rate). How much confidence is placed on the diagnostic strength of these measures needs to be cautiously considered, but they do potentially contain patient-specific trend data. These can be emailed to the practice by the patient to aid with diagnostic decision making.

Formulation element

It is essential to write an impression, which includes documentation of the primary diagnosis.

I also usually try to write a prioritised short differential list. This provides an excellent reflective cue to thought processes during the initial consultation if the patient re-presents in the future.

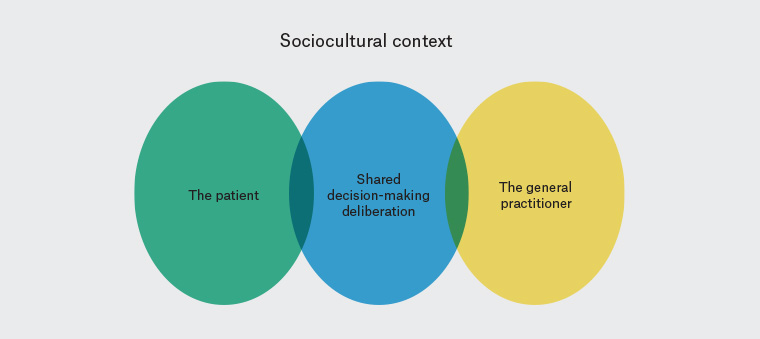

Any telemedicine consult and subsequent diagnosis has more inherent uncertainty factored into its deliberation. Therefore, most ‘impressions’ will tend to have a broader consideration of the potential differentials. It is crucial to be cognisant that any formulations are unconsciously biased to the ‘history’ and any ‘prior medical history’ elements, because of the obvious paucity of the ‘examination’ elements. It is essential the GPs acknowledge this when discussing their clinical opinions with their patients. The telehealth consult is a ‘shared care’ experience for all parties (Figure 2).10–14

Figure 2. Shared decision-making diagram of key elements10

Management element

The management is limited and restricted to the patient context. Any advice may require adopting novel solutions that are patient specific.

However, the initial position is to consider the management initially as that regarding what advice would be given to the patient during a face-to-face consultation (ie best practice).

From that position, the final management plan is adapted by applying the unique elements of the patient’s situation.

Management examples include:

- completing any e-forms for the patient and returning them to the patient

- faxing/mailing/emailing off scripts to a pharmacy at which the patient has an account, and pre-arranged delivery service.

It is imperative to document clearly the management plan in the patient’s encounter/record, including reasoning if it deviates from the standard of care.

It is important to document any instructions given to the patient if the agreed management fails to remedy their complaint. The follow-up provisions documentation is a critical element in the telehealth consult. It is beneficial to provide some written version of that advice if possible.

Closing the patient encounter element

The final element of the consult focuses on confirmation by the patient of their understanding of the consult.15

I ask the patient to outline 1) what they understand as the diagnosis, and 2) the important elements/components related to the condition, as pertaining to themselves as the patient.

This includes:

- duration of the condition

- essential critical historical elements

- the absence or presence of key physical features/signs.

It is crucial to ask the patient to confirm elements of the medicines being prescribed. The patient needs to repeat any instructions related to ‘how to take the medications’, ‘how often’, ‘with what’ and ‘when to stop’. It is important to educate the patient about the potential common and significant adverse effects that may be experienced, as well as any actions to take and/or whom to contact if adverse effects occur.

The next steps are to:

- confirm any follow-up advice

- ask the patient if they have any questions, or if the issues they presented with have been addressed

- close the consult.

Post-consult element

If not done previously, the practitioner should now:

- complete the clinical note in the patient’s record, documenting the telehealth medium used in the record (eg video conference platform, telephone, etc)

- complete any other outstanding ‘paperwork’ related to the consult, and designate and disperse relevant information to the appropriate facility/service

- manage the mechanics of billings

- schedule follow-up appointments if needed.

It is essential to recognise that this is a crucial non-clinical element to be completed before the next clinical encounter while the narrative is still fresh and accurate.

Final thoughts

The telemedicine consult is not significantly different from the more traditional face-to-face consult. It uses a practitioner’s pre-existing skill set and shares many of the common elements of the face-to-face patient–clinician interaction.

The assessment is strongly weighted towards the history and presenting complaint. The use of general observations and potential available serendipitous devices within the remote patient’s environment can be a novel solution to broadening the examination and investigation elements of the assessment.

The consultation does need to be framed with a degree of clinical caution.3 The diagnosis and management should be openly shared with the patient, with whom the GP is effectively sharing care. This caution should also be noted in the patient’s records.

Sometimes, as the telehealth consult progresses, it becomes evident that the patient’s reason for consulting a clinician is of a complexity that exceeds the telehealth context.9 This situation should prompt the clinician to consider if there is a need for further assistance in their patient’s care in some other manner, such as moving to a face-to-face consult or seeking a second opinion from a specialist, peer or supervisor.

It is important to remember the value of the follow-up consult. It allows a review of how the issue or complaint is progressing. It provides clinically valuable feedback to the clinician and is appreciated by the patient.16

There will be unique elements to the local environment; adaptation and the intention of preserving best practice is the key. It is also something at which primary care medicine excels