Case

A woman aged 40 years presented for a cervical screening test (CST). She was a mother of three and a recently arrived refugee. She had never had a Pap smear or CST in the past because she had been living in a remote area for decades. The purpose of the test was fully explained to the patient. When asked before the procedure about routine symptomatology including menstruation, discharge and itchiness, the patient had no complaints.

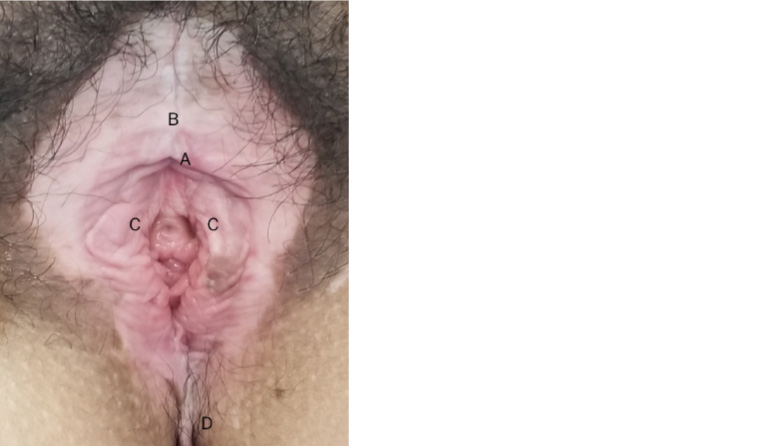

During the procedure, in the presence of a chaperone female practice nurse, whitish discolouration of the vulva, involving both labia majora and minora, and clitoris with distorted anatomy was noted (Figure 1). On further enquiry, the patient stated she had experienced mild pruritus for several years, and she thought it was due to friction from walking.

Figure 1. Lichen sclerosus of vulva with some anatomical distortion (A = Buried clitoris,

B = Involvement of clitoris hood, C = Distorted labia minora, D = Extending to perineum)

Question 1

What is the differential diagnosis based on this presentation, and what is the most likely diagnosis?

Question 2

How will you definitively diagnose this condition?

Answer 1

Given whitish discolouration of the vulva in a woman aged 40 years, the differential diagnosis for this particular case can include:1,2

- lichen sclerosus of the vulva (LSV)

- vitiligo

- lichen simplex chronicus

- lichen planus

- post-inflammatory hypopigmentation

- morphoea

- extramammary Paget disease

- vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN).

The pale-white and ivory-white discolouration of the vulva and clitoris with some anatomical distortion make LSV the most likely diagnosis in this case. If there is a prominent erythematosus with scales, then psoriasis and contact dermatitis can also both be considered as differential diagnoses. Table 1 compares and contrasts the features of LSV with other similar conditions.

| Table 1. Differential diagnoses of lichen sclerosus of the vulva9–13 |

| |

Primary lesion features |

Main symptom |

Genital involvement |

Extragenital involvement |

Possible dermoscopic features |

Histology/microscopy |

| Lichen sclerosus of the vulva (LSV) |

White patches with sclerotic skin texture, fissures, erosions |

Prominent

itch (+++) |

Very common (80%) |

Rare

(15–20%) |

White structureless areas with linear vessels, ice slivers, comedo-like openings (hair-bearing area) |

Hyalinisation of upper dermis, with a band of lymphocytes below; atrophic or hyperkeratosis epidermis |

| Vitiligo |

Well-defined depigmentation with no alteration of skin texture |

No itch |

Less* |

More common* |

Homogenous white structureless areas with absent or reduced pigment network |

Total absence of functioning melanocytes, with the inflammatory lymphocyte on the edges of the lesions |

| Morphea |

Thick, hard skin (sclerotic/fibrosis) |

No itch |

Rare |

More common* |

White-yellowish structureless areas, linear vessels within the lilac ring |

Atrophic epidermis with increased collagen in the dermis and loss of appendageal structures |

| Lichen planus |

Hypertrophic erosions of the vaginal introitus (LSV does not affect vaginal mucosa) |

Pain is greater than itch |

Less* |

More common* |

White crossing streaks (Wickham striae) |

Hyperkeratosis and acanthosis; saw-toothing of rete pegs, band-like chronic inflammatory infiltrate obscuring the dermo-epidermal junction |

| Lichen simplex chronicus |

Lichenification with scaling |

Itch (+++); scratching is pleasurable |

Less* |

More common* |

Scales, exaggerated skin markings |

Marked hyperkeratosis associated with foci of parakeratosis, prominent granular cell layer, papillary dermal fibrosis |

Dermatitis

(atopic/contact) |

Erythematosus with or without scaling and lichenification |

Itch (++) |

Common, depending on triggers |

Common, depending on triggers |

Red dots in a patchy distribution and yellow scales |

Extensive spongiosis; initially acute spongiotic dermatitis, evolving into subacute or chronic spongiotic dermatitis |

| Psoriasis |

Erythematosus with or without scaling and fissures |

Itch (+) |

Less* |

More common* |

Scales and dotted vessels; under high-power imaging, dilated, elongated and convoluted capillaries are visible |

Regular acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis, supra-papillary plate thinning |

| Cicatricial pemphigoid |

Blisters (bullae) or erosions |

Pain |

Rare |

Mouth |

NA |

Immunofluorescence analysis – linear deposition of immunoglobulin (Ig) G or IgA, and complement (C3) at the basement membrane zone |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis |

Red, inflamed mucosa with white-curd discharge |

Itch (+++) |

Common |

NA |

NA |

Confirmation of candidiasis using vaginal swab for microscopy, culture and sensitivities |

Note: Itch is classified as mild (+), moderate (++) or severe (+++)

*When compared with LSV

NA, not applicable |

Answer 2

A diagnosis of LSV can be made clinically without a mandatory biopsy. However, a punch biopsy from the white sclerotic area is highly recommended to confirm the diagnosis and exclude alternative diagnoses including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The histopathology usually illustrates atrophic or hyperkeratotic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrate in the dermal–epidermal junction and the homogenisation of collagen in the upper dermis.2–4

Case continued

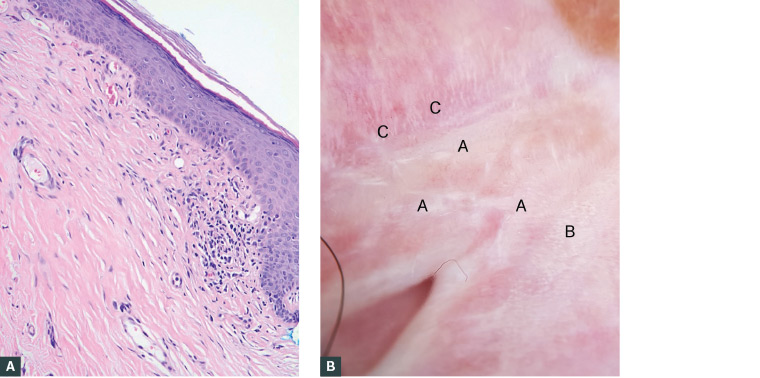

The patient was informed about the unusual discolouration and the possibility of a genital skin disorder. She was scheduled for a biopsy to guide management and rule out SCC. The biopsy confirmed lichen sclerosus with no evidence of neoplasia (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Histology and dermoscopy of lichen sclerosus of the vulva (LSV)

A. Histology of LSV; B. Dermoscopy of LSV (A = Structureless white patches [sclerosus], B = Ice sliver, C = Scattered linear vessels mixed with the whitish structure)

Question 3

What is lichen sclerosus and what are the clinical features of LSV?

Question 4

What are the aetiology and epidemiology of LSV?

Answer 3

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis commonly affecting the anogenital region. The condition is characterised by white sclerotic patches that subsequently coalesce, becoming shiny porcelain-white or ivory-white colour. When it affects the vulva, it is called vulvar lichen sclerosus or LSV. It was previously known as lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, kraurosis vulvae, leukoplakic vulvitis and lichen albus. When it affects the penis, the term balanitis xerotica obliterans has been used historically.1,5

Occasionally LSV can be asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during CST.3,6 The possible clinical manifestations of LSV include:

- pruritus (often intractable), pain and bleeding from fissuring and erosion

- dyspareunia and other sexual dysfunction

- constipation and painful defecation if perianal skin is involved

- atrophy and distortion of anatomical structures including burying of the clitoris, fusion or loss of labia minora, stenosis of the introitus, and distortion of urethral orifice resulting in urinary problems.

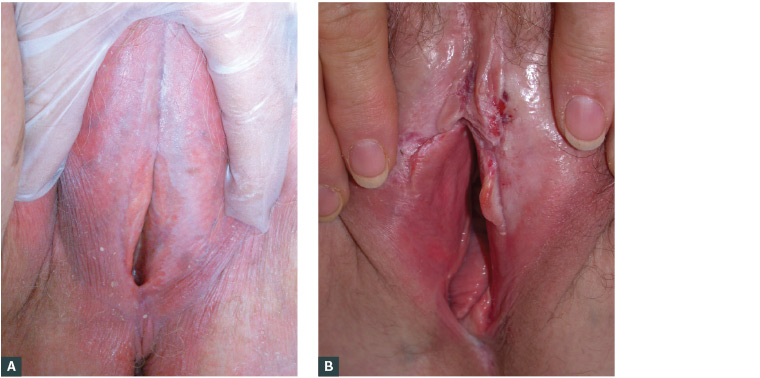

Morphologically, LSV results in an atrophic or hyperkeratotic surface of the vulva with white sclerotic papules, patches or plaques, which may extend to the perineum and perianal area. Areas of purpura, fissures and erosion can sometimes be seen. Extragenital lichen sclerosus, which predominantly affects the shoulder, neck, thigh, buttock and breast, is seen in 15–20% of cases.2 Figure 3 shows various morphologies of genital lichen sclerosus.

Figure 3. Various morphology of lichen sclerosus of the vulva (LSV)

A. LSV with typical shiny porcelain-white vulva (image courtesy of DermNet NZ); B. LSV with erosion and fissures (image courtesy of DermNet NZ)

Dermoscopically, patchy white structureless areas, ice slivers, comedo-like openings (hair bearing area only), purpuric globules and dotted or sparse thin linear vessels can be seen (Figure 2).3

Lichen sclerosus can be associated with autoimmune-related diseases such as thyroid disease, vitiligo, alopecia areata and pernicious anaemia.2,7

Answer 4

The exact aetiology of lichen sclerosus remains speculative. Several theories such as autoimmune (approximately 20% association), genetics (12% positive family history), hormonal factors and chronic trauma/irritation have been proposed.1,7,8 LSV commonly affects individuals from the fifth decade onwards but can be seen at any age including prepuberty. Approximately 30–50% of affected women develop symptoms prior to menopause.6,9 The prevalence of LSV is estimated to be one in 30 older women and one in 900 prepubertal girls.1 Most scholars suggest that genital lichen sclerosus is underreported because of a number of factors: lack of awareness of the patient and practitioner; embarrassment and reluctance to disclose symptoms; and presentation at different practitioners of general practice, sexual health, gynaecology, urology and dermatology.1,3,6 As a result, delays in diagnosis and undertreatment are not uncommon. Although earlier literature reported that lichen sclerosus and LSV generally affect individuals of Caucasian descent, the condition can be seen in patients of any ethnicity.1

Case continued

The patient underwent a blood test for autoantibody screening, and the results showed no associated autoimmune disorders; such investigation is not routinely required for every case. She had no other skin disorders. She was referred to a dermatology clinic at public hospital. While waiting to be seen by a specialist, the patient was treated with potent topical corticosteroid (TCS; mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment) with general advice as per current guidelines. She had some improvement in symptoms and skin texture within six weeks.

Question 5

What are the complications of LSV?

Question 6

What are the management options for LSV?

Answer 5

The complications of LSV are:

- anatomical distortion/alteration – as described in the clinical manifestations, resulting in sexual dysfunction plus urinary and bowel opening problems

- psychological – LSV significantly affects the individual’s sexual function and quality of life, resulting in psychological distress and low self-esteem

- cancer – there is an increased risk of vulvar SCC of approximately 5%.1,2

Answer 6

Goals of treatment are to: 1) alleviate symptoms of pruritus, fissuring and pain, 2) improve sexual function and quality of life and 3) reduce scarring (structural distortion) and risk of cancer.8 The detailed management for LSV is outlined as follows.

Ultra-potent or potent TCSs are the first line of treatment. They provide both symptomatic relief and clinical improvement, reducing complications of scarring and malignant change.3,4,9 TCSs (one fingertip unit = 0.5 g) are applied twice daily until symptoms (itchiness, soreness) are relieved (1–2 weeks), then reduced to daily application until the return of normal texture of the skin (usually 1–2 months), and later on alternative days, totalling approximately three months from the start of treatment. Afterward, maintenance treatment using lower potency (mid-strength) TCSs such as betamethasone valerate (0.02%), triamcinolone acetonide (0.02%) or methylprednisolone aceponate (0.1%) twice weekly is generally recommended. Frequency of TCS application can be individualised depending on hyperkeratosis. Ointment-based TCSs are commonly preferred to cream in genital areas because of better absorption as well as barrier function.6,9 TCS therapy is safe and inexpensive to use, and it is effective in 90% of patients.10

It is advisable to review the patient in 4–6 weeks and three months from the start of TCS therapy. A 6–12-monthly follow-up is recommended during maintenance treatment. Treatment failure at any stage indicates the need to consider an incorrect diagnosis, noncompliance issue, development of VIN or SCC, or superimposed factors such as allergic reaction to specific medications, infection (candida, virus [herpes simplex virus], bacteria [Staphylococcus spp., Gardnerella spp.]), and irritation from excess sweat or urinary and faecal incontinence. There is no role for topical testosterone and oestrogen.

General measures include the following:

- Counsel patients about the nature of disease, course, treatment and need for follow-up. Some individuals may need reassurance that lichen sclerosus is not a sexually transmissible infection.

- Advise patients to avoid scratching and irritants to the genital area by using soap substitutes for cleaning and applying a protective barrier (eg soft paraffin or emollient) to minimise the contact with sweat, urine and faeces. Other vulvar irritants may include hygiene products, creams, lubricants, contraceptives and procedures (eg improper hair removal). Tight underwear and any activities that can rub onto the sensitive mucosa (eg riding a bicycle or horse) should also be avoided.10,11

- Advise patients to become familiar with the appearance of their genital area, as lifelong monitoring is required to detect, diagnose and treat new lesions or scarring.

Consider multidisciplinary care involving a local vulvar clinic (if available) or dermatologist or gynaecologist with an interest in lichen sclerosus. For example, surgery for correction of anatomical distortion or treatment of early carcinoma may be needed.

Discussion and conclusion

General practitioners (GPs) have an opportunity to detect genital skin lesions while performing a CST. It is prudent for GPs to be familiar with characteristic features of genital skin disorders to be effectively able to carry out further actions. Early detection and treatment with timely referral for genital skin disorders such as LSV will reduce the impact on the patient’s morbidity both physically and mentally. Management of vulvar skin disorders spans dermatology, gynaecology and sexual health, and referral to a pertinent specialist is recommended depending on the severity and complication of the disease. The prognosis of LSV is usually favourable if diagnosed and treated in the early nonscarring stages.

Key points

- Genital skin disorders are generally underreported because of various factors.

- GPs have an opportunity to detect genital skin lesions while performing a CST or investigating a patient’s direct concerns.

- Early detection and treatment for genital skin disorders such as LSV will reduce the impact on the patient’s morbidity physically and psychologically.