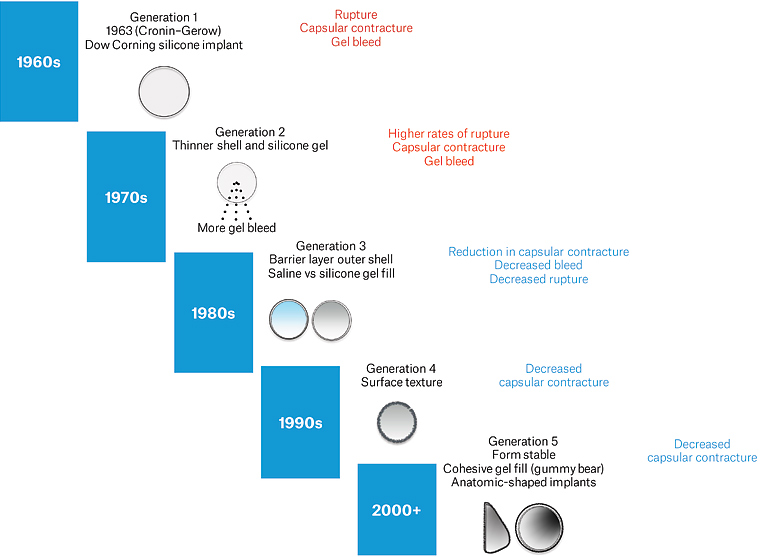

Breast implants have been in use for reconstruction or augmentation since 1962. Initial breast implants were primarily silicone based with a smooth surface. In 1991, there was an increase in number of adverse events reported, including hardening, rupture and a possible link to autoimmune disease from silicone.1,2 Subsequently, in 1992 the US regulator, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) imposed a ‘voluntary moratorium’ on silicone breast implants, restricting their use to breast reconstruction or for replacement following device failure.1 This resulted in a large class action lawsuit.3 However, for the rest of the world, there are no restrictions for silicone breast implants. Since the early 1990s, newer technologies have been introduced, including the texturisation of the outer shell, cohesive gel fill and anatomic shapes (Figure 1).4

Figure 1. Generations of breast implants. Click here to enlarge

Subsequent to the Dow Corning crisis, there have been two further major regulatory actions related to breast implants. In 2010, a French-based implant manufacturer was found to be using non-approved industrial-grade silicone.5 This resulted in the recall of products and government-sponsored implant removal in the UK. The founder of the company was tried, convicted and jailed. In Australia, the Poly Implant Prothèse (PIP) crisis was the impetus for the establishment of the Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR).6 The second crisis related to implants occurred in 2019–20. During this time, there was an increase in the number of cases of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), a T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which resulted in certain implant types being cancelled or suspended worldwide.7–9

It is also important to consider that some patients undergo breast implant surgery overseas as part of a growing cosmetic tourism industry. Recent analysis has shown that cosmetic surgery performed overseas carries significantly higher risks of complications, notably infection.10

Types of breast implants

Breast implants can be classified based on their surface, fill and shape.

Implant surface

The outer shell of breast implants can vary significantly. Initially, breast implants were designed with a smooth outer shell. Texturisation was introduced in the late 1960s in an attempt to promote better tissue ingrowth and increase the implants’ stability and longevity. There are number of different methods for imparting texture to the outer shell, including the use of imprinting, salt impregnation, gas vulcanisation and polyurethane coating. Jones et al proposed a numeric grading system ranging from grade 1 (smooth) to grade 4 (polyurethane) based on the measurement of surface area/roughness.11

Implant fill

Implants are typically filled with silicone gel or less commonly saline.

Implant shape

Implants are round (or spherical) or anatomic in shape. Anatomic implants require some surface texture to prevent rotation in the pocket.

Clinical use

Breast implants are used for four common indications:

- cosmetic breast augmentation

- post-mastectomy breast reconstruction

- congenital deformities of the chest/breast

- transgender surgery.

Breast augmentation remains the most popular elective cosmetic surgical procedure worldwide. Approximately 20,000 women undergo this procedure each year in Australia, with 75% for cosmetic augmentation and 25% for reconstruction.12 Implants can be placed either above or partly below the pectoralis major muscle and can be inserted via a submammary (most common), peri-areolar or axillary incision. For women who have lost volume of the breast, either through weight loss or post-lactation, a breast lift (mastopexy) can be performed in combination with augmentation. This will leave a visible scar on the breast, usually in the shape of an inverted T, or less commonly around the areola. Implants are also used in transgender surgery (male to female) to create a breast mound, usually in conjunction with oestrogen supplementation.

For post-mastectomy reconstruction, implants can be placed either immediately following mastectomy or after a period of tissue expansion. Expanders are used to stretch the skin/muscle pocket over a period of 3–6 months prior to conversion using a definitive gel implant. The use of mesh or dermal sheets to support the implant can also be used to control implant placement and/or reinforce the soft tissues.

Complications following breast implant insertion

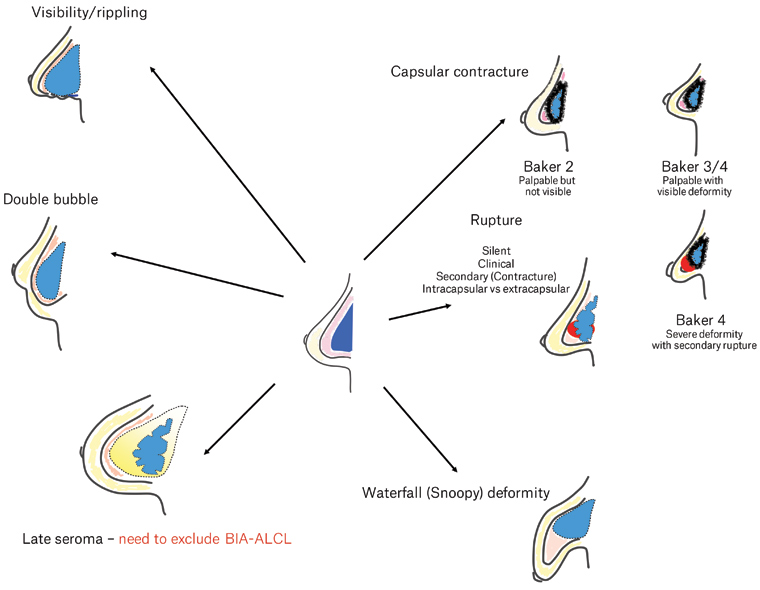

Breast implants are not lifetime devices; they have an estimated lifespan of 10–15 years. The risk of adverse events begins to accumulate after the device is inserted (Figure 2). These can be classified into local (breast or implant related) versus systemic, and further subclassified into acute and medium/long term. Table 1 summarises the local complications following breast implant surgery.12 In general, the risks associated with post-mastectomy reconstruction are higher than with cosmetic augmentation. Added to this are the risks of radiation and/or chemotherapy that can increase the risk of local implant complications. Patients with associated comorbidities, such as diabetes, obesity and smoking, also increase the risk of adverse events, especially infection.

| Table 1. Local adverse events in women with breast implants |

| Implant related |

Breast related |

- Capsular contracture

- Rupture intracapsular/extracapsular/silent

- Rotation

- Displacement: double bubble, axillary migration

- Visibility/rippling

- Deflation (saline filled)

- Folding

- Breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

|

- Parenchymal ptosis: waterfall (Snoopy) deformity

- Breast pain

- Benign breast lumps

- Breast cancer

|

Figure 2. Adverse events resulting from breast implants. Click here to enlarge

BIA-ALCL, breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Acute complications

Infection, haematoma, implant exposure and seroma are acute complications following breast implant surgery and account for less than 5% of adverse events.12 Pain, swelling, redness, discharge and wound breakdown 1–2 weeks following surgery require urgent referral to the treating doctor. Acute postoperative infection requires early intervention with antibiotics, surgical debridement and pocket irrigation to salvage the implant. If there is progression, however, the implant is usually removed. It would be reasonable to attempt replacement following a period of antibiotic therapy and tissue rest.

Capsular contracture

Capsular contracture is the most common reason for revision surgery (Figure 3).13 This presents as progressive hardening, distortion and deformity of the breast due to the development of a thick, fibrous capsule around the implant. The principal cause of capsular contracture is the development and growth of a low-grade bacterial infection attached to the surface of the implant (biofilm), which stimulates inflammation and fibrosis over time.14 Other postulated causes include haematoma and/or foreign body reaction. Patients present approximately 3–5 years following initial surgery, and the rates vary from 5% to 9% over 5–10 years’ post-implantation.15 The use of stringent bacterial mitigation (eg pocket irrigation with antibiotics/antiseptic and ‘no touch’ insertion) when implants are placed in surgery has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of capsular contracture.16–18 Severe capsular contracture can cause secondary implant rupture due to infolding, friction and weakening of the outer shell. Capsular contracture is graded clinically using the Baker grade (Table 2).19

Figure 3. Right-sided grade 4 capsular contracture 10 years following primary breast augmentation

| Table 2. Baker classification of capsular contracture18 |

| Baker grade |

Description |

| 1 |

Breast implant is soft and is not palpable and/or visible (for women with breast implants for reconstruction). Grade 1B is where the implant is soft but visible, as the skin envelope is thinner |

| 2 |

Implant is palpable, but no visible deformity |

| 3 |

Implant is hard, palpable and with some minor visibility (eg puckering, rippling, change in shape). Ultrasound usually shows infolding |

| 4 |

Implant is very hard and painful with significant deformity of breast and/or malposition. Ultrasound shows significant folding and/or rupture |

Implant rupture

Disruption of the implant shell and leakage of contents is termed ‘implant rupture’. The contents can be held within the capsule (intracapsular) or leak into the surrounding breast tissue and/or lymph nodes (extracapsular). Extracapsular rupture may present as an acute foreign body reaction with swelling, redness and induration of the breast and surrounding chest wall. The patient may experience a sudden change in shape or projection of the breast, or in some cases may be completely unaware of the rupture (termed ‘silent rupture’). This requires timely surgery for removal. Rupture is best detected by screening ultrasonography and can be confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Implant mobility and visibility

The movement of the implant from its original pocket may cause visibility and/or palpability of the implant outer shell. This can manifest as a double bubble appearance, where the implant moves below the inframammary fold or into the axilla (Figure 4). In some patients with very thin parenchyma or weight loss following surgery, implant folding or rippling can also be seen and felt. For anatomic implants, rotation of the device can also cause distortion of the breast shape.

Figure 4. Left-sided double bubble

Waterfall (Snoopy) deformity

This deformity occurs when the breast and parenchyma drop below the position of the implant (Figure 5). It can occur after pregnancy/lactation and fluctuations in weight. Treatment usually involves implant exchange with a breast lift (mastopexy).

Figure 5. Waterfall deformity bilaterally shown in three-quarter right view

Breast pain

Pain in and around the breast implant is usually related to capsular contracture. Other causes of breast pain, including breast lumps, fibrocystic change and hormonally induced changes, can be timed with the menstrual cycle. Musculoskeletal strain and costochondritis also need to be considered. It is common after surgery to have some neuralgia from the axillary and lateral thoracic nerve branches. Nipple sensitivity (either decreased sensation or hyperaesthesia) can also occur following breast implant placement.

Breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Reports of a rare T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma occurring around breast implants have increased over the past decade.19 It is not classified as a breast cancer. BIA-ALCL has now been definitively linked to breast implants, and more specifically, textured surface devices.7,9,20–22 Clinically, this tumour manifests most commonly as a malignant effusion with fluid build-up in the space between the implant and capsule, causing swelling and pain approximately 7–8 years following the initial procedure (Figure 6). In approximately 10–15% of women, BIA-ALCL presents as a peri-implant mass, usually detectable on ultrasound, which can subsequently spread to axillary and mediastinal nodes. Currently, there have been over 100 confirmed cases in Australia with four deaths.23 The risk of BIA-ALCL is higher for implants with higher grades of texture.24 The current accepted hypothesis for causation proposes that higher-grade texture provides a template for the growth of bacteria, ultimately transforming genetically susceptible T cells into lymphoma over time.24 This theory is supported by clinical, laboratory and epidemiological evidence. All women considering breast implant surgery should be informed of the relative risk of BIA-ALCL based on the type of implant recommended. Latest evidence has estimated the risk as one in 2000–3000 for devices with a grade 3 or 4 surface.25 To date, there are no cases arising from exposure to smooth (grade 1) devices alone. The Australian regulator has now cancelled grades 3 and 4 devices in response to this risk.

Figure 6. Late right seroma. This patient had benign pathology. She also had bilateral waterfall (Snoopy) deformity.

A patient with suspected BIA-ALCL should proceed to breast ultrasonography and sampling of the peri-implant seroma. The presence of abnormal tumour cells that are CD30 positive and anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative confirms the diagnosis. For patients who present with a mass and no effusion, ultrasound-guided biopsy or open biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Once diagnosed, patients should be referred to a multidisciplinary team with expertise in breast cancer/reconstruction and be clinically staged using MRI/computed tomography–positron emission tomography. In approximately 88% of women in Australia, the tumour is detected in the earliest stages, when it is confined to the seroma and inner lining of the capsule. For these patients, surgical removal of the implant and capsule is curative. For more advanced disease, adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy and immunotherapy are indicated.

Breast implant illness

Some women present with a range of systemic symptoms thought to be related to breast implants. These symptoms are diverse and include brain fog, memory loss, myalgia, arthralgia, rashes, gastritis, hair loss, dyspnoea and loss of libido.26 The term ‘breast implant illness’, which has coalesced as a term to describe this condition, remains poorly characterised. Studies investigating likely pathogenesis, natural history and outcomes following explantation are underway.26 Patients are encouraged to register with one of these prospective trials.

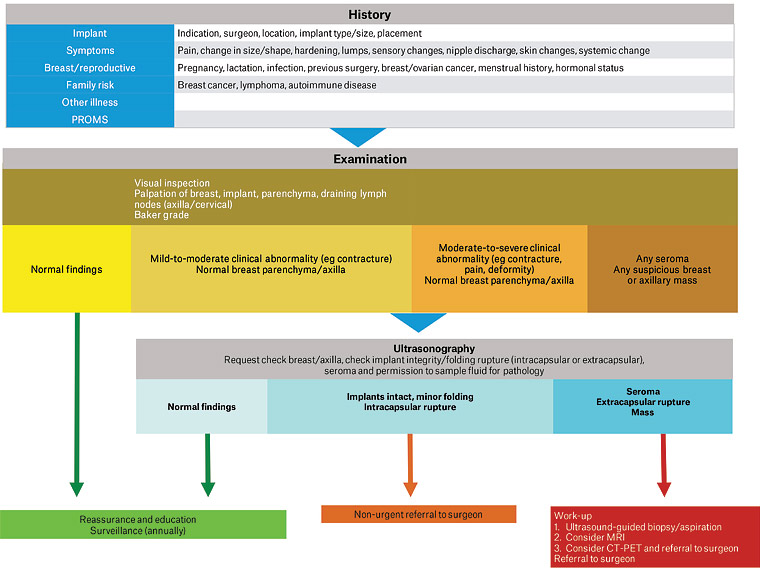

Clinical approach to breast implant assessment

Figure 7 outlines a clinical, investigative and management flowsheet for the assessment of breast implants, and the diagnosis and management of non-acute complications.

Figure 7. Clinical approach to the assessment of patients with breast implants, and the diagnosis and management of non-acute complications. Click here to enlarge

CT-PET, computed tomography–positron emission tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PROMS, patient-reported outcome measures

History

All patients are now encouraged to keep details of their implant on a patient card. Some patients may also be now registered on the ABDR. A thorough history covering the following points should be taken:

- Implant history: indication for surgery, date(s) of procedure(s), type of implant (size, surface, brand, shape), placement of implant (above or below muscle), name of treating practitioner and location of surgery

- Symptoms related to implant and/or breast: pain, change in shape of breast, hardness/palpable lumps, deformity, change in sensation of nipple, nipple discharge and skin abnormalities

- Systemic symptoms: fatigue, joint pains and skin rashes

- Breast and reproductive history: pregnancy, lactation/breastfeeding, breast cancer/ovarian cancer history, menstrual history and hormonal status

- Other concurrent illness

- Family history of cancer (including lymphoma) and autoimmune disease

- Any recent imaging results.

Examination

Clinical examination should include a thorough examination of the breast, parenchyma and draining lymph nodes. Visual inspection, with arms by the side and raised above the head, of abnormal contour, visible lumps and skin changes should be noted. The degree of capsular contracture can be clinically assessed using the Baker grade (Table 2). The presence of any asymmetry or associated chest wall abnormalities should also be noted and documented. It is good practice to document the appearance on photographs with frontal, left and right three-quarter views (with the patient facing at a 45-degree angle) and right and left lateral views, if possible.

Investigations

If there is a clinical abnormality, a breast ultrasound is the gold standard for detecting implant rupture, seroma or any peri-implant or capsular mass. A mammogram is also indicated if the patient has a high risk for breast cancer or where a patient has not been previously screened. Many women with breast implants wrongly assume that mammograms are not possible with implants in situ. A displacement technique can be used safely to protect the implant from damage.

At any stage in the work up, referral to the original surgeon who placed the implant should be considered. The need for regular surveillance of women with breast implants is becoming both recognised and recommended. Many surgeons now conduct their own follow-up care for their patient cohort and have incorporated this into their standard of care.

Summary

With a significant proportion of the population accessing breast augmentation or reconstruction, it is useful for general practitioners to become familiar with how to assess patients with breast implants and detect potential adverse events. In the aftermath of recent regulatory action, there are many understandably anxious patients who will require assessment and assurance, and in the event of a problem, timely diagnosis and treatment.