Acute kidney injury (AKI) is characterised by a rapid reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR).1 Criteria from the organisation Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) rely on an acute elevation in serum creatine (>26.5 µmol or >50% from baseline) or oliguria to define AKI in adults and determine its severity from stage 1 (‘mild’) to stage 3 (‘severe’).1 Without recent creatinine measurements, differentiating AKI from unrecognised CKD can be difficult, and urine output is often imprecisely measured. AKI affects 8–20% of adults admitted to hospital and approximately half of patients in intensive care units.2 Acute kidney replacement therapy (KRT) is initiated in approximately 1% of all hospitalised patients.3

AKI is a heterogenous syndrome but is often precipitated by extrarenal disease in at-risk patients. The classification of ‘pre-renal, renal and post-renal’ causes can ensure differential diagnoses are considered. The most common cause is acute tubular injury due to a combination of hypoperfusion, sepsis or medications that produce toxicity or compound hypoperfusion (eg antihypertensives).4 While AKI can occur in patients without underlying health problems, it is particularly common in elderly patients and those with comorbidity, particularly chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure and chronic liver disease (Figure 1).

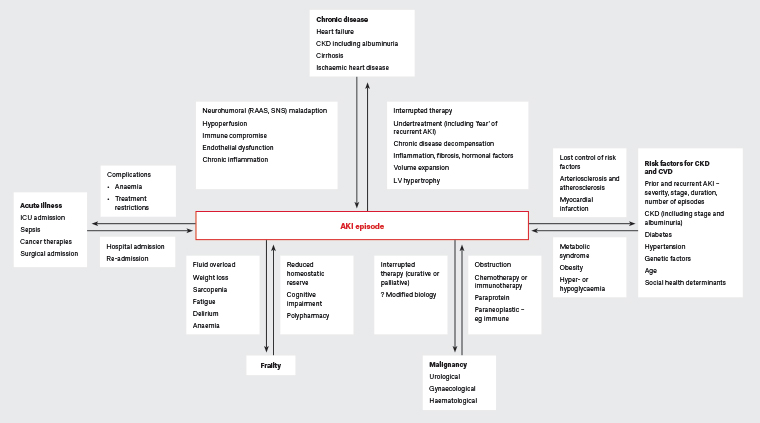

Figure 1. Two-directional relationship between chronic or acute disease and acute kidney injury. Click here to enlarge

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ICU, intensive care unit; LV, left ventricle; RAAS, renin–angiotensin aldosterone system; SNS, sympathetic nervous system

There is a relationship between all stages of AKI and later morbidity and mortality, even when GFR returns to baseline.5 While higher rates of comorbidity in patients with AKI explain and mediate some of the poor outcomes seen, careful observation has shown that episodes of AKI are independently associated with adverse events for up to 10 years (Figure 1).1,6 By 90 days, 20–29% of patients are readmitted to hospital.7,8 Adjusting for other factors, AKI approximately doubles the risk of subsequent death.9 In one large study examining survivors of AKI, 12-month mortality was 28%.10 Common causes of death included cancer (28%) and cardiovascular disease (CVD; 28%), with mortality ratios reaching eight times those of the general population.10

The period after AKI represents an opportunity to improve care.6,11 However, lack of advocacy, resource and policy constraints, and competing health priorities limit the attention given to AKI.6 The benefit of specialist post-AKI clinics remains unproven.12 Thus, general practice represents the coalface of this important problem, particularly in rural and remote areas.

Few overarching guidelines address the period post-AKI.6,11 Although a UK collaborative has developed an AKI Toolkit (www.rcgp.org.uk/aki) that includes discussion of post-AKI care, it has a distinct local perspective. The aim of this review is to highlight common challenges and offer suggestions to help guide the management of survivors of AKI. Table 1 provides a summary.

| Table 1. Suggested management priorities after acute kidney injury |

| Diagnosis |

| Documentation |

- Clarify whether patients and carers understand the diagnosis of AKI.

- Document the AKI episode in medical records and incorporate it into treatment plans.

|

| Address complexity |

- Clarify patient priorities, including holistic care, education and quality of life.

- Recognise common issues ‘beyond GFR’ (eg persistent effects of acute illness, anaemia, cognitive impairment and frailty).

|

| Case-finding |

- Unrecognised CKD and cardiovascular disease, especially heart failure, are common.

- Hypertension and diabetes may be unrecognised or may emerge.

|

| Preventive healthcare |

- Revisit healthy lifestyle measures and immunisation.

- Screen for cardiovascular or CKD risk factors and malignancy within existing guidelines.

|

| Management challenges |

| Medication interruptions |

- Seek clarity about why medications have been interrupted if this information is missing.

- Timely medication adjustments reflecting further changes in GFR (eg antimicrobials, anticoagulants, analgesia and diabetes therapies).

|

| Chronic disease management |

- ‘Permissive AKI’: tolerate an acute GFR reduction to permit long-term benefit.

|

| Sick-day advice |

- Identify medications that might accumulate dangerously, or exacerbate hypoperfusion, renal toxicity or hyperkalaemia with acute illness.

- Sick-day medication interruptions should be accompanied by prompt review (eg to recognise unanticipated hypertension or hyperglycaemia).

|

| AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate |

Diagnostic priorities

Communication and AKI

Synthesis of AKI into the patient history and management plans can inform screening, case-finding, prognosis and management.1,13 However, approximately half of AKI diagnoses in Australian inpatient settings are missed or poorly communicated at discharge, representing a practice and policy challenge.14 Incorporating AKI into decision support software is an attractive solution that is undergoing research.15

Addressing the patient experience and complex care needs

Small series examining patients’ experiences of AKI report a desire for holistic care, education and quality of life.6 Holistic care is important, as following AKI there is an increased prevalence of systemic problems including anaemia,16 infection17 and musculoskeletal disorders.18 Because AKI often accompanies complex admissions and comorbidity,19 a narrow focus on GFR or volume state may fragment care and produce poor outcomes. For example, palliative care services are underutilised by patients with AKI.20

Frailty is a distinct risk factor for, and potential consequence of, AKI21,22 and increases the risk of subsequent death.10 The interplay between AKI and frailty encompasses comorbidity and complications of AKI. Figure 1 illustrates some potentially modifiable elements.

Screening and case-finding: Cardiovascular or CKD risk factors

Review after AKI may unearth modifiable risk factors for CVD and CKD. Diabetes is prevalent among survivors of AKI,23 but potentially unrecognised24 and new-onset diabetes is independently increased in survivors of AKI.25 AKI also predisposes to subsequent hypertension.26,27

Diagnostic guidelines for diabetes recommend case-finding after a CVD event but do not cover case-finding for diabetes28 or hypertension after AKI.27,29 These authors suggest case-finding for diabetes and hypertension after an AKI episode. Many patients will warrant longer-term case-finding as well as lipid assessment on the basis of existing risk factors and guidelines.

AKI, CKD and acute kidney disease

AKI and CKD are interconnected, sharing risk factors, outcomes and prognostic factors.30,31 Both disorders indicate an increased likelihood of subsequent AKI, kidney failure, CVD, diminished quality of life, disability and death. Prognosis is affected by the duration and number of AKI episodes and the stage of either AKI or CKD (Figure 1).30

When features of AKI persist between seven and 90 days, the term acute kidney disease can be applied,31 although this terminology is not widely used. CKD is defined by an estimated GFR (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73m2 or evidence of kidney damage (eg albuminuria, haematuria, or structural or pathological abnormalities) for ≥3 months and is staged according to eGFR and albuminuria.13,32

While eGFR and albuminuria estimation at three months post-AKI is appropriate,31 earlier review may uncover CKD, thus far unrecognised because of a lack of healthcare engagement or CKD screening, or a failure to communicate or interpret historical results.6,23 AKI is also appropriately included among eight triggers to initiate ongoing kidney health checks.13

Heart failure and cardiovascular disease

The bidirectional relationship between heart failure and AKI or CKD is termed ‘cardiorenal syndrome’,33 with shared risk factors and pathophysiology (Figure 1). AKI and CKD both predict incident heart failure.34 After AKI, concurrent heart failure increases the risk of early readmission;29,35 overall, acute decompensated heart failure is the most common cause of hospital readmission.19,36

Established or new presentations of ischaemic heart disease are also common. For patients with ischaemic heart disease, the presence of AKI is similarly associated with greater readmission rates and complications.37

Malignancy

The high incidence of death from malignancy noted after AKI10 is intriguing and potentially challenges the existing focus on CKD, CVD and metabolic factors (Figure 1). However, most cancers are known at the time of AKI,10 and applying existing cancer screening recommendations currently seems appropriate.

Management priorities

Healthy lifestyle and immunisation

Lifestyle is a cornerstone of good health. Physical activity, healthy diet, salt minimisation, weight optimisation, smoking cessation, appropriate vaccination (especially influenza, pneumococcus and COVID-19)38 and alcohol reduction underpin any pharmacotherapy6,13 and may help prevent rehospitalisation.39

Evidence-based resources that encourage independence and healthy eating are usually suitable.40 However, conflicting advice may confuse patients. For example, strategies to limit dietary potassium in patients at highest risk of hyperkalaemia41 may inadvertently direct patients away from diets rich in fruit and vegetables, which reduce the development of CKD, constipation and metabolic acidosis (all of which can worsen hyperkalaemia), as well as hypertension.41–44 Counselling from accredited dietitians is likely useful to help manage suspected nutritional deficiency or persistent hyperkalaemia.

Managing medication interruptions

Despite limited evidence, medication interruptions are common in patients with AKI.1,4,31 Commonly, such interruptions aim to avoid:

- pharmacokinetic concerns

- medication accumulation with reduced GFR

- pharmacodynamic concerns

- worsening AKI via systemic and renal hypoperfusion

- worsening AKI by direct toxicity

- exacerbating hyperkalaemia, hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia or other metabolic disturbances accompanying AKI.4,45

Just as adjustment to medications should accompany a fall in GFR, there must be timely adjustment as GFR recovers. Antimicrobials and anticoagulants are commonly renally cleared and warrant particular attention to avoid critical therapeutic failures.

For patients with unresolved oliguria, advanced CKD or heart failure, volume control can be helped by redefining a weight-based trigger for medical review, and potentially fluid restriction or a diuretic sliding scale.46 Interim ‘standard’ blood pressure targets (<140/90 mmHg) are likely appropriate until recovery is complete, recognising the significant benefits of lower long-term targets for many patients.29,35

Medication interruption may be poorly explained or accompanied by vague directions to ‘avoid nephrotoxics’ without further clarification. Clarifying the instructions and optimising important medications is an important task after AKI.45

Just how medication review affects post-AKI outcomes is unclear. International panels31,47 have recommended prioritising review – within as little as three days – on the basis of AKI stage, poorer GFR recovery, comorbidity (particularly heart failure) and functional impairment. These recommendations presuppose recognition and communication of AKI diagnoses and may be difficult to accommodate in systems geared to chronic care. Research clarifying the early role of telemedicine, deprescribing tools, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physicians and general practitioners (GPs) in providing optimal and cost-effective care is justified.6,31

Permissive AKI

Strategies that address volume control, hypertension and neurohumoral factors are often feared because of a perceived tension between the heart and kidneys.48 One example is the use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in the management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).49,50

More strategies that present similar tensions in addition to important prognostic benefits have recently arrived. These include assertive hypertension management in selected patients at high cardiovascular risk,29,35 combined angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) in HFrEF,48 sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in HFrEF or CKD,51–53 and specific mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) for CKD.54

Concern about recurrent AKI is understandable, and acute falls in GFR are common when introducing these strategies and in the natural history of heart failure.48,55 However, while these treatment-related falls in GFR may meet formal definitions of AKI, they appear not to produce the long-term harms common to AKI overall.48,55 Generally, these strategies improve important long-term CKD outcomes51–54,56,57 or have ‘extrarenal’ benefits such as reducing the incidence of stroke.29,35 Specifically, despite concerns regarding hypoperfusion and a predictable effect on GFR with initiation, neither SGLT2 inhibitor, ACE inhibitor nor ARB prescription appears to increase the overall risk for recurrent AKI.58–60

The term ‘permissive AKI’ has been coined to describe acceptance of a potential reduction in GFR to minimise long-term CVD or CKD.48 Patients can be reassured that a fall in GFR is acceptable if:

- the decline in GFR is anticipated

- there are no alternative explanations (eg infection, gastrointestinal losses, true nephrotoxics)

- there is an important likely benefit (eg slowing CKD progression or CVD)

- no other important complications emerge (eg hyperkalaemia, acidosis, potential medication toxicity)

- there is a sensible monitoring plan for detecting complications.48

Despite a ‘permissive’ strategy, monitoring of potassium and GFR remains important, particularly to inform dosing of renally cleared medications (eg pregabalin). The risk of medication interactions and polypharmacy must be balanced with potential benefits. Without clear evidence regarding the introduction of combination therapy, it seems prudent to introduce or re-introduce these medications sequentially and titrate to target doses.

Clinical and biochemical review within two weeks of medication changes will usually be appropriate.13,61 The use of novel potassium binders (eg patiromer) to offset medication-related hyperkalaemia has been proposed62 but is not established or subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Heart failure after AKI

Extensive guidelines, beyond the scope of this review, frame the management of heart failure.46 However, beyond fluid and hypertension control, particular priorities for AKI survivors with heart failure include:

- improving access to multidisciplinary management, particularly for patients at high risk of rehospitalisation46

- optimising medication strategies with prognostic benefit, including ACE inhibitors/ARBs and vasodilatory β-blockers for HFrEF. Subsequent, evidence-based use of medications with diuretic effects (ARNIs, MRAs and SGLT2 inhibitors) will often make reduction or cessation of loop or thiazide diuretics – not clearly associated with mortality benefits – possible and appropriate.46

Diabetes after AKI

Recent changes to glucose-lowering medications – especially temporary or new use of insulin – present distinct challenges. Ensuring safe insulin administration and adjustment, self-monitoring of blood glucose, avoidance of hypoglycaemia, and fitness to drive are early priorities. Prompt referral to a credentialled diabetes nurse educator (DNE) may complement medical input.63

Sick-day advice

The provision of ‘sick-day advice’ also lacks robust evidence of benefit.64,65 However, it appears prudent for patients at high risk of recurrent AKI. These authors suggest the following.

- Identify medications with risk of hypoperfusion, dangerous accumulation, toxicity or exacerbating hyperkalaemia. Mnemonics highlighting some high-risk medications (eg ‘SADMANS’ for sulfonylureas, ACE inhibitors, diuretics, metformin, ARBs, NSAIDs and SGLT2 inhibitors) are offered within CKD guidelines as prompts;13 however, other glucose-lowering medications, antivirals, anticoagulants, antiarrhythmics, analgesics and sedative medications are particularly prone to acute accumulation66 and should be considered as high-risk medications in the setting of AKI.

- Instruct patients to withhold such medications when they experience vomiting, diarrhoea, reduced oral intake or other serious illness.

- Provide permission and instruction to seek prompt medical attention, because

- acute illness, including AKI, may paradoxically produce hypertension and hyperglycaemia, warranting an escalation of specific therapies

- vulnerable patients often need further medical interventions on ‘sick days’.64

Advice should balance the risks and benefits of briefly stopping medications; be individualised; include translation, written instructions or visual aids; consider existing strategies for chronic medications (eg Webster Packs); and involve carers and other clinicians, including pharmacists.

The big picture

Most patients are not cared for by a nephrologist during or after AKI. Currently the predominant reasons for nephrology referral are ongoing KRT, immune- or paraprotein-mediated AKI or existing CKD. Most nephrology clinics and guidelines remain oriented to such problems.13 International resources should be better adapted to suit local perspectives.

While GPs excel at holistic care, selected patients probably benefit from non-GP specialist services after an episode of AKI.67 This includes patients requiring specialised medications (eg potassium binders), allied healthcare (eg renal dietitians) and disease-oriented services (eg DNEs or heart failure clinics). Further efforts should define the best model of care for AKI survivors and better integrate research into chronic disease guidelines and existing services.

Conclusion

Patients who survive AKI are at high risk of hospital readmission and death, particularly over the following year. Attention to several common areas is likely to improve individual patient outcomes.

Key points

- AKI increases the risk of hospital readmission, kidney disease, CVD, disability, frailty and death.

- Several diseases are recognised as risk factors for and potentially underlie AKI, including CKD, cardiovascular risk or disease, and possibly malignancy.

- The acute response to AKI often involves withholding or reducing the doses of medications that may have important long-term prognostic benefits. Rational reintroduction and dose adjustment of medications – mindful of polypharmacy and toxicity – is a complex but important task.

- Improved outcomes after AKI likely require improved policies and clinical structures to provide timely, coordinated and optimal care to the patients at greatest need