Methamphetamine use is an ongoing global public health concern.1 In Australia, some associated harms are increasing, as indicated by increasing methamphetamine-related ambulance and treatment presentations.2 To effectively prevent and respond to methamphetamine-related harms, it is crucial that people who use the drug are able to access appropriate professional support.

Access is a critical determinant of health service utilisation, described as the ‘fit’ between consumers and the healthcare system, whereby supply of services is matched with population demand.3 Well-developed, accessible health service systems have been associated with a reduction in aggregate alcohol and other drug (AOD)-related harms at a population level.4

Previous research indicates that people who use methamphetamine in Australia access a variety of generalised and specialist services, including general practitioners (GPs), emergency departments (EDs), psychiatric, psychological and specialist AOD service providers (possibly via a centralised referral system, such as the Australian Community Support Organisation [ACSO]).5–9 Yet modelling suggests that nearly 50% of the demand for specialist AOD services in Australia is unmet;10 therefore, primary care services need to be accessible to consumers who use methamphetamine.

Little is known about barriers to accessing care for people who use methamphetamine, in particular from providers’ perspectives. This is especially the case in non-metropolitan areas, despite recent data indicating higher levels of dependence among non-metropolitan people who use methamphetamine, together with unprecedented media interest in methamphetamine in rural areas.8,11 Barriers to accessing care are particularly concerning in rural communities, and these barriers are associated with poorer health outcomes for consumers who misuse substances or who have poor mental health.12–14

This study aimed to explore rural primary care providers’ understandings of access to and service utilisation by consumers who use methamphetamine.

Methods

The researchers used a qualitative multisite case study design broadly informed by Creswell, incorporating clearly identified, well-bounded cases.15 Case study methodology focuses on real-life, contemporary contexts and is characterised by an in-depth understanding of a specific issue. In this study, that issue is the accessibility of primary care services in rural towns where there has been unprecedented media coverage regarding the use of ‘ice’.11 The cases were general practice clinics and specialist AOD providers. The guiding methodology was derived from the conceptualisation of access,16 best described as a dynamic and interactive approach that takes into account the demand for and supply of healthcare in the process of seeking and obtaining care. This approach includes dimensions of access, and these were used to inform the research questions and methods, particularly the data collection and analysis (Table 1).

| Table 1. Access dimension definitions16 |

| Availability and accommodation |

Health services (either the physical space or those working in healthcare roles) can be reached both physically and in a timely manner |

| Affordability |

The economic capacity for people to spend resources and time to use appropriate services |

| Acceptability |

Cultural and social factors determining the possibility for people to accept the aspects of the service |

| Appropriateness |

The fit between services and clients’ needs, its timeliness, the amount of care spent in assessing health problems and determining the correct services provided |

| Approachability |

People facing health needs can actually identify that some form of services exists, can be reached and have an impact on the health of the individual |

The study was set in two large rural towns (Modified Monash Model category 3) in Victoria,17 each of which had a high prevalence of methamphetamine-related presentations to specialist AOD services.18 The results reported here were part of a larger project,19 which included a secondary analysis of quantitative data about characteristics of people who use methamphetamines (not reported here), and qualitative interviews with primary care and specialist AOD providers.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit providers with varied perspectives on the issue across a range of disciplines and from diverse practice settings.15 Details of general practice providers (GPs, practice nurses [PNs] or allied health staff) and specialist AOD providers were provided by the Primary Health Network (PHN). Invitations were sent to 62 general practices by email or mail, followed by phone calls to practice managers. After staff from only two practices agreed to participate, personalised invitations signed by one author (a practising Fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners), were posted to GPs (n = 65). Snowballing via service contacts was also used.

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted face to face or via telephone by one researcher. Interviews followed a guide informed by the access framework and results of a large, recent study of methamphetamine use in Victoria.8 Questions covered participants’ professional role, skills and perceptions of how people who used methamphetamine accessed local services, either directly or via referral. Interviews were 30–60 minutes long and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were returned to participants for checking; no interviewees made changes. There was no prior relationship between the interviewees and interviewer.

De-identified data was managed using NVivo 10.20 Two researchers (BW, RL) with AOD and qualitative research experience read and reread transcripts and analysed all interviews independently. The within and cross-case thematic analysis accounted for context. Data relating to access were coded deductively, according to the dimensions of access.16 Data relating to influences on and improving access were coded inductively.15 Coding differences were resolved between BW and RL. The Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethics approval (No. 12085). Private sector interviewees were reimbursed with $150 vouchers.

Results

Of the specialist AOD services, 62 practices and 65 GPs approached, eight staff across the two towns agreed to be interviewed, five in general practice settings and three in specialist AOD services (Table 2). The difficulty in recruiting general practice staff for this study may be a finding in itself. During follow-up telephone calls, practice managers indicated that general practices saw few patients who use methamphetamine, so GPs/PNs would be unable to contribute usefully. For confidentiality reasons, town names and specific details of services have not been provided.

| Table 2. Characteristics of interviewees |

| Person |

Pseudonym |

| PN at an ACCHO |

PN ACCHO 1 |

| Long-time private practice GP |

Private GP 1 |

| GP with both custody and private practice |

GP custody/private 1 |

| GP with both custody and private practice |

GP custody/private 2 |

| GP at an ACCHO |

GP ACCHO 2 |

| Nurse manager of a CHS |

AOD manager CHS 1 |

| PN at an AOD service |

AOD nurse 2 |

| Manager at an AOD service |

AOD manager 2 |

| ACCHO, Aboriginal controlled community health organisation; AOD, alcohol and other drugs; CHS, community health service; GP, general practitioner; PN, practice nurse |

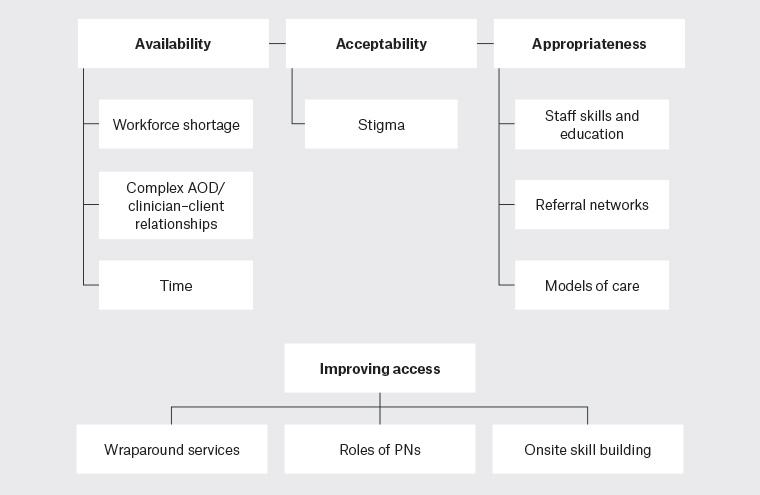

The analysis identified four overarching themes: availability, acceptability, appropriateness and ideas to improve access. There were no data regarding the dimension of ‘approachability’. Affordability (for consumers) was reported as not significant. Themes and related subthemes are outlined in Figure 1 and in text with illustrative quotes, differentiated by general practice and specialist AOD staff.

Figure 1. Data analysis themes and subthemes

AOD, alcohol and other drugs; PNs, practice nurses

Availability

All participants mentioned that a general workforce shortage for GP services limited access for complex AOD clients. Ongoing availability of staff and time were deemed essential to providing continuity of care for clients who use illicit substances.

Complex AOD/clinician–client relationships versus workforce shortage

AOD specialist workers reported that many GPs do not want to see AOD clients, especially those who use methamphetamine, as they are seen as ‘problematic’ clients. Concerns about aggressive behaviour and regulatory legalities were reported. One AOD specialist noted:

The more middle-class aimed family practices that are very selective about who they let in. ... You can’t do that in the UK because you’re on a government contract (AOD manager community health service [CHS] 1).

GPs reported that they sometimes see these clients, but do not need any extra clients, given workforce shortages. This was particularly noted for GPs in private practice:

We’re not looking for the business … If the [family] come here, we might go out of our way. All GPs are very busy, so why bother? (GP custody and private practice [custody/private] 2).

Several participants reported that AOD clients are not seen in general practices, particularly those who use methamphetamine and the complex polydrug-using groups. Availability of GPs was seen as essential to the development and maintenance of an ongoing positive clinician–client relationship, particularly for clients to disclose their drug use and seek help.

Time

Participants reported general practice time pressures as a major barrier to appropriate treatment. In the context of a business model that was perceived to prioritise short appointments, GP participants felt it was difficult to build therapeutic relationships that facilitate AOD use, disclosure and treatment referral. Both general practice and AOD specialist participants highlighted that current funding arrangements inadequately support longer appointments:

In this [cohort], the [Medicare Benefits Schedule] model is a disaster. It rewards activity not quality outcomes … so the presenting complaint tends to be [the] complaint that gets focused on (Private GP 1).

Acceptability

Explanations for not seeing clients who use methamphetamine were often linked to acceptability and stigma related to methamphetamine use/disclosure: GP custody/private 1 noted that clients may ‘feel more comfortable if they know that it’s advertised that it’s a GP that has an interest in drug and alcohol withdrawal’, but such disclosure was limited.

Participants’ perceptions on the impact of stigma varied. AOD nurse 2 reflected on her ED experiences of attitudes towards clients who use drugs:

They said ‘oh, look at that’ … judgemental the whole time. Mind you, they don’t say it about all the drunks coming out of the RSL.

For private GP 1, stigma was key:

The biggest hurdle … is the marginalisation and stigmatisation that goes with illicit drug use. [We] need to be much more accepting that these people frequently become drug addicts unintentionally and don’t want to continue.

Other interviewees echoed this, describing a good clinic as where ‘all of the staff actually treat people with respect, but also being non-judgemental’ (AOD nurse 2). GP custody/private 2 described how practice staff subtly make it known that the patient is not welcome back:

I think there’s stigma attached. … The practice reception staff have to overcome their biases and say this patient is a worthwhile human being and needs to have access.

Appropriateness

The ability to spend time and develop skills to work with AOD clients was highlighted. Knowledge and availability of specialist referral services was identified, as were different models of general practice.

Staff skills and education

Both general practice staff and AOD specialists spoke of a few GP ‘flagbearers’ who had prescribed opioid substitution therapy (OST) for many years. In contrast, they felt that many mainstream GPs face difficulties in asking clients sensitive questions about drug use and mental health, which preclude the provision of appropriate care. To address this, the PHN had funded training for GPs, with limited uptake; ‘only five GPs attended a recent education night’ (AOD manager 2). AOD manager CHS 1 noted:

Firstly, they don’t want to know anything about it. ... Secondly, they’re getting bombarded with requests ... not only in relation to people using methamphetamine, but for opiate users. It is difficult to get GPs to prescribe opioid replacement therapy or attend training sessions.

Referral networks

General practice staff were often not familiar with or users of AOD referral pathways and networks, with GP custody/private 1 stating: ‘Sometimes you seek the information when you need to and I haven’t had to do that yet’.

The centralised referral system (ACSO) was strongly criticised by most participants. It was perceived to delay appropriate (ie continuous, coordinated and timely) care. AOD manager 2 noted that they could not change the ACSO intake model, stating that ‘staff were pretty unhappy about it’ and that GPs now ‘might just give the client ACSO’s details’. Prior to the state-based healthcare reorganisation for clients with AOD problems that led to the introduction of ACSO, clients may have called the nurse and been given a same- or next-day appointment:

The informal relationships [between GPs and AOD services] are critical, and as a result of the reform, we don’t have that informal relationship any longer (AOD manager 2)

While delays to accessing outpatient or community-based AOD services were reported, the lack of residential options was highlighted. Discharge from justice/custody systems, where people are likely to have effectively withdrawn from drugs, but lack crucial support post-release, was also reported as highly problematic, with poor communication to AOD and GP services.

As reported by GP Aboriginal controlled community health organisation (ACCHO) 2, ‘the prison system; it appears to be really setting people up to fail’.

Similarly, GP custody/private 2 stated:

They get sent off to Melbourne ... to prison … three months later they get released, they’ve still got the same circle of friends ... the same sources of drugs and they go back to using, even though maybe they’ve been successfully detoxed.

Models of care

ACCHO and CHS staff thought that their system often works better with a multidisciplinary team routinely asking about and recording drug use, including methamphetamines, usually with integrated records. PN ACCHO 1 noted that when referring internally, there is better sharing of records than with private GPs or between the ACCHO and external AOD services: ‘Aboriginal health can bypass ACSO delays and poor information flows’. AOD manager CHS 1 stated that their service has access to notes within CHS, with some restrictions.

Improving access

Three broad ideas were identified for improving access to GP and AOD services for people using methamphetamine: 1) introducing ‘wraparound’, multidisciplinary services; 2) upskilling PNs and administrative staff; and 3) supported, onsite skill building for GPs, rather than offsite education sessions.

Wraparound services with links to GPs

Many of the participants supported the concept of coordinated, multidisciplinary services, ideally with all healthcare professionals on one site. The ACCHO and CHS models were thought to be a good starting point:

The more hardcore [meth] users … need more of an intensive wraparound service … than what [AOD services] the state government currently funds (AOD manager CHS 1).

This would be similar to child protection services that were ‘targeted at high-needs clients’ (AOD manager CHS 1).

Upskilling PNs and administrative staff

Participants viewed PNs as critical for managing referral pathways to AOD services and assistance with the management of OST clients. However, while agreeing with the need to upskill nurses in AOD, private GP 1 commented:

If we focus on any one member of the team more than the others, we lose sight of what we really need: a genuine team-based approach.

GP custody/private 2 had suggestions for dealing with problematic behaviour. All staff needed to accept a ‘harm minimisation [approach]; the criminalisation of drug use doesn’t work’. In that framework, disruptive behaviours, such as swearing, can be dealt with by seeing these clients ‘before their turn … get them in and get them out’ and training clients that they need to return to get their script. This highlights the need for PN and administrative staff training to be part of a whole-of-practice approach.

Supported, onsite skill building to train GPs

Given poor uptake of offsite AOD education by GPs, there were suggestions for onsite training. GP ACCHO 2 drew lessons from their experience of AOD skill building around prescribing buprenorphine:

We had an addiction GP [at the CHS]. When I first started, we booked a one-hour appointment and got in a [AOD] nurse. We went through with the patient and that’s how I learned, to build my confidence … But if it’s on my own, I don’t think I would do it … Teaching [GPs] caring is easy … the practical stuff is a bit difficult. [You need] a distinct specialist at that practice and they’ve built that relationship [with] the doctor.

AOD manager 2 was keen to improve relationships with GPs, stating ‘I’d really like to know what the GPs want from us, how we can help them’. They can visit towns, meet with hospital and GP staff, offer to work with them and provide education. A key need is to recruit an addiction medicine specialist. They ‘have a nurse practitioner candidate, but I don’t think that … hits the mark for general practitioners’.

Discussion

This study’s findings indicate that, for consumers who use methamphetamine, access to a primary care workforce in rural Australian towns may be difficult. The researchers identified challenges in accessing appropriate care within a rural setting for clients who use methamphetamine. There were workforce shortages across the primary care system, clear signs of social stigma towards people using methamphetamine and a general perception that GPs were reluctant to offer care to clients who exhibit problematic behaviours. Primary care providers seemed to lack knowledge of some aspects of clinical care. The referral system was difficult to negotiate, leading to delays in accessing appropriate and coordinated care for this vulnerable population.

If general practice is the most common point of access to the healthcare system for consumers who use methamphetamine,21 addressing the acceptability of primary care services is critical. Rural Australians ‘trade-off’ these dimensions of access; just having a service available is not enough to ensure utilisation.22 Access is more than just the supply of health services; it relies on service demand. Some consumers who use methamphetamine do so without being dependent or experiencing methamphetamine-related harms.8,23 Some reduce/abstain from use spontaneously. Attitudes (and possibly stigma) towards those who use methamphetamine are reflected in some interviewees’ reports that many GPs and other clinicians prefer not to provide services for these consumers, and that some staff proactively dissuade them from seeking further service access. In the context of poor GP availability, efforts to support consumers who use methamphetamine need to address the required ‘skill mix’, that is, the availability of the necessary set of skills across an organisation. This differs from ‘staff mix’, which focuses on the perspective of individual disciplines.24 A focus on skill mix enables shifting tasks within a team to respond to variations in demand. This requires a workforce that can work in teams with individuals, families and communities at the interface of healthcare, social services and the criminal justice system.25

Consumers’ demand for services is a function of their abilities to perceive, seek, reach, pay and engage with health services.16 These are underpinned by health beliefs, literacy, personal and social values and factors, such as housing, income and social capital.16 Addressing these factors does not fit easily with the current traditional model of general practice, as reflected in the data. GPs are the most common source of healthcare for consumers who use methamphetamine,8 yet general practice interviewees perceived they do not see many clients who use methamphetamine. This may be attributed to a lack of knowledge regarding the characteristics of people who use methamphetamine and other drugs. Similarly, some GPs may not have/utilise AOD history-taking skills. In addition, the MBS model of care may act as a disincentive for consumers to disclose methamphetamine use, and for providers to develop skills and provide adequate consultation time to address the factors that underpin consumers’ capacity to demand healthcare services. Evidence suggests that the current primary care model is inadequate to meet the needs of consumers who use methamphetamine, whether they are seeking services for their methamphetamine use, use of other drugs or for different reasons.

For consumers who use methamphetamine, access may be limited by the degree to which the healthcare system addresses underlying social determinants of misuse of illicit substances. Australian longitudinal studies have found no significant difference in methamphetamine dependence at one or three years, regardless of treatment utilisation.23 Those who showed the poorest outcomes had higher levels of use prior to treatment entry, injected methamphetamine and experienced higher levels of psychological distress and psychotic symptoms.26 Understanding the characteristics of this high-risk subgroup of consumers who use methamphetamine can inform the provision of accessible primary care.

There were limitations to this study. There were difficulties with recruitment, and therefore, requests were reframed as general AOD use, with some focus on methamphetamine. Despite this, saturation was reached, as the predetermined themes were adequately reflected in the data.27 The analysis suggests general practice staff may face difficulty and discomfort in providing services to this cohort of clients, and therefore, may be less likely to engage with pertinent resources. This also has implications for further research in this area. Research is needed to evaluate models of care that improve access for people who use methamphetamine, particularly in rural areas, and how, if at all, this is associated with health outcomes.

Conclusion

In this study, most primary care providers reported perceiving that they do not have clients who use methamphetamine (and in some cases, are reluctant to see them). This contrasts with reports from Australians who use methamphetamine. The known subgroup of people who use methamphetamine fits with that of a vulnerable, disadvantaged population. There is a need to move from the focus on supply (availability) of health services to match consumer demand with the availability of acceptable and appropriate services. In the context of poor GP availability, efforts to support consumers who use methamphetamine need to address the required ‘skill mix’, that is, the availability across an organisation of the necessary set of skills. This may require a shift in how and where care is delivered.