Mental health issues are common in the Australian community, with approximately 3.2 million Australians experiencing an anxiety-related condition and 2.5 million experiencing feelings of depression each year.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has brought fears relating to the virus itself (eg potential exposure of self and family), anxiety about physical distancing and concerns regarding unemployment and economic loss.2 Since the start of the pandemic, the Australian Government has announced that more than $500 million will go towards boosting key mental health services, supporting the National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan.3 Unsurprisingly, general practitioners (GPs) have been called upon to provide increased mental health supports for their patients, further adding to their significant clinical workload.

The COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns, associated loss of employment and financial stresses, navigation of homeschooling for parents while working from home and isolation of school-age children from their peer groups created a ‘perfect storm’ for the exacerbation of existing mental health conditions and the development of depression or anxiety. Further consequences included a reported spike in domestic violence and an increase in reported alcohol consumption.4,5 In some parts of Australia, COVID-19 closely followed devastating bushfires, meaning some communities were already in a heightened state of anxiety and stretched beyond their normal capacity.2,6

In high-income countries, GPs are central to providing mental healthcare,7 and are the first point of contact for mental health presentations and the facilitators of access to other therapists.8,9 Psychological issues are the most common health issues managed by Australian GPs.10 GPs often have longstanding relationships with their patients, and are well placed to understand their personal, family and community contexts and appreciate the interaction of concurrent physical and other mental health conditions and medication use.

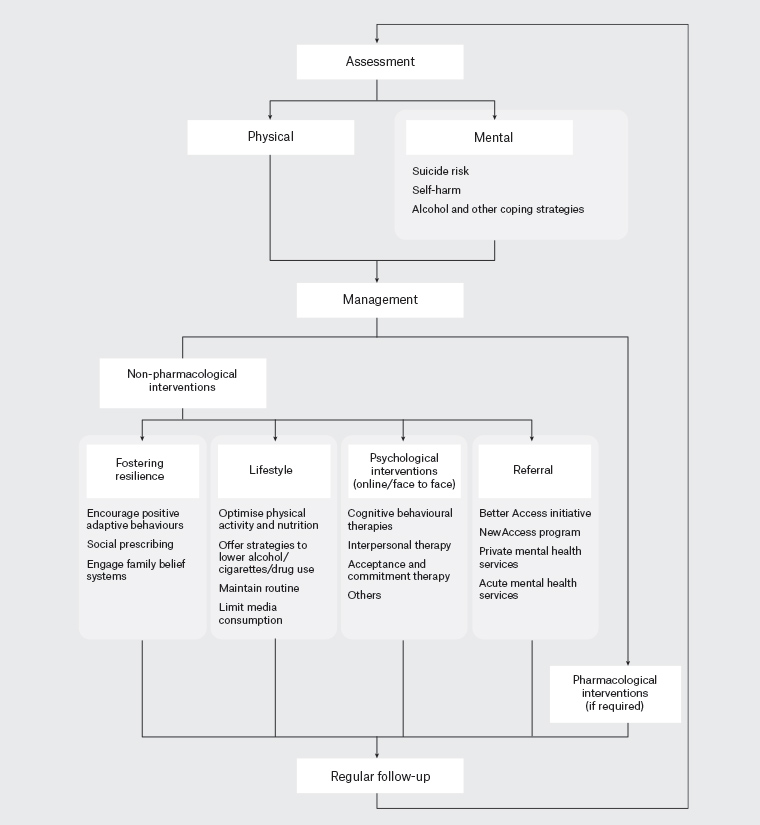

With increased demand for mental health services during the pandemic, GPs need to provide increased mental health supports while keeping up to date with pandemic-specific guidelines and adapting to new methods of delivering healthcare. Furthermore, GPs themselves are experiencing similar worries and uncertainties related to potential infection of self and family, conflicting home and work commitments, as well as financial implications of the pandemic on practice viability. This article aims to offer guidance for GP management of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic by providing an overview of management approaches (Figure 1), a list of resources (Table 1) and two case studies.

Figure 1. Overview of management approaches for mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic

Assessment

Apart from assessing presenting complaints and personal and family history of mental health conditions, a psychosocial history (ie coping methods, social supports and socio-occupational functioning) is essential to understand the full impact of the pandemic on an individual’s mental health.11 Screening for mental health issues is particularly important for those with pre-existing mental health problems, healthcare workers, those in quarantine and the unemployed and casualised workforce, all of whom are known to be at increased risk of mental illness during a public health emergency.2 A mental health risk assessment should be considered in vulnerable patients for early detection of mental health problems or even suicidal thoughts.12 It should be noted that some people may present having already assessed their mental health by using tools available online.13–15 Regular follow-up to reassess symptoms and ensure that diagnoses and interventions are appropriate is important, as mental health issues can deteriorate over time.

Management

Fostering resilience

The presence of increased anxiety, loneliness and sadness are expected in the context of a pandemic, and is not necessarily diagnostic of a mental health condition.2,16 GPs can help patients keep perspective and encourage positive behaviours, such as keeping up connections with friends and family, even in the presence of worry, pessimism and negative emotions about the pandemic.

While family resilience frameworks emphasise communication, organisation and belief systems, these are likely to be disrupted during a pandemic.17 GPs can help their patients reinforce such processes by focusing on the three Rs: routines, rituals and rules.17 Maintaining routines, developing new rituals and renegotiating rules so that they are still applicable during the pandemic can strengthen shared family values.17

Other models developed to manage emotional responses to natural disasters focus on the three Cs: control, coherence and connectedness.18 Control is reflected in the belief that people can access personal resources to achieve valued goals. Strengths-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can also be used to facilitate control, with patients encouraged to construct personal models of resilience that identify personal strengths, and then use metaphors and imagery to navigate challenges.19 Coherence is related to people’s desire to make sense of the world.18 Encouraging a view that families are ‘in it together’, and that their current plight is specific, not the fault of anyone and time limited and manageable, may reinforce beneficial belief systems.17 Despite the impact of social distancing, isolation or quarantine requirements, connectedness can be emphasised with fewer people with whom patients have more meaningful relationships, or by expanding social contacts in ways that are not dependent on face-to-face engagement.18 Finally, ‘social prescribing’, where people are referred to non-clinical services, support groups and social structures, can be helpful for people experiencing mental health issues, chronic physical health conditions or social isolation.20,21

Lifestyle

Tobacco smoking, inadequate nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption and physical inactivity are behaviours that contribute to greater chronic disease burden, including for those with mental health issues.22 Optimising aspects of physical health, by focusing on healthy eating and regular exercise, should be discussed.23,24 More minutes of daily exercise and more days per week spent outside in the sunshine for at least 10 minutes have been found to predict greater resilience during COVID-19.25 Coping mechanisms and strategies to minimise cigarette and alcohol use should be addressed. The Australian Government’s Head to Health website provides helpful resources on physical activity, nutrition and sleep.26 Media reports can be a source of stress, and patients should be encouraged to monitor and limit their media consumption and rely on official and trusted sources of information.2,23,27

Psychological interventions

Several psychological interventions can assist people with mental health conditions. Favourable results have been reported for CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and acceptance and commitment therapy, even when delivered remotely and in multiple contexts,28–30 as is often necessary during the pandemic. CBT aims to modify maladaptive, automatic, negative thoughts and can reframe fears relating to hopelessness about social connection or fear of infection, whereas IPT allows the pandemic to be framed as a role transition.31 Promisingly, CBT, IPT and computer-assisted therapies have good evidence of effectiveness for common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.32,33

Referral

Most GPs are familiar with the Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists and General Practitioners Initiative (Better Access), funded through the Australian Government’s Medicare Benefits Schedule. During the pandemic, recognising the immense value of these psychology sessions, the Australian Government extended the program funding up to 20 sessions per calendar year.34 For people with milder symptoms, another option is referral to coaches in the NewAccess program, developed by Beyond Blue and available in a number of regions of Australia (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory at the time of writing).35 People can self-refer to NewAccess for a total of six sessions and do not need a mental healthcare plan.35

Pharmacological interventions

While specific pharmacological therapies are outside the scope of this article, a few basic principles are worth reiterating. Knowing a few medications well (ie the short- and long-term side effect profiles, medication interactions and medication–disease interactions) enables prescribers to be more confident in starting medications when needed. Once medications are started, patients should be followed up to monitor their progress and potential side effects. Special groups of people that should be treated with increased caution include older people, people with chronic disease, pregnant/breastfeeding women, children and adolescents.11 A detailed discussion of the various pharmacotherapies is outlined in the Psychotropic section of the Therapeutic Guidelines.36

Case 1

Bob, aged 54 years, is a patient you know well. He presents three months after the date for his scheduled review of diabetes management. He has a history of metabolic syndrome and major depressive disorder. He lives alone. His main supports are his siblings, but they live in another state. Bob reports that he has been feeling down, and although he denies any active suicidal plans, admits that ‘getting Corona might be a blessing’. He remains on the same dose of antidepressant medication and did not attend his last scheduled session with his psychologist, as it was over the telephone and ‘what would be the point?’ His investigations reveal glycated haemoglobin of 9.8%.

Bob has a pre-existing mental health condition, is socially isolated and has a serious chronic physical health condition. Options for management include:

- assessment of symptoms using tools, such as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9), General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD7) or Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21)

- reiterating Bob’s suicide safety plan

- emphasising the role of the 3Rs. Encourage Bob to stick to a regular routine (eg getting dressed at the same time every day and taking medication at the same time). Bob can develop new rituals, such as having dinner ‘virtually’ with his siblings a few times a week. New rules, such as having an hour of ‘digital detox’ or a 10-minute walk every day, can be trialled

- consideration of social prescribing of an activity that interests Bob. Examples of potential activities include walking, gardening, speaking to his siblings over the telephone, doing a shared project with his siblings (eg genealogy, cooking using television cooking shows/online recipes as a guide, painting or drawing that he can be encouraged to bring to appointments or taking courses/volunteering with the local men’s shed

- discussion about lifestyle interventions, such as physical activity and Bob’s current diet, that are likely contributing to poor diabetes control. It may be worth discussing that improving Bob’s diet and exercise may help improve his mental health as well

- making sure Bob’s vaccinations are up to date, especially influenza and COVID-19 vaccinations

- encourage mindful engagement in activities and referring Bob to the Head to Health website for further information

- discussion about current coping mechanisms (eg alcohol consumption, smoking) and providing relevant supports

- reassuring Bob that psychological interventions conducted remotely are still effective, and encouraging Bob to re-engage with psychology

- consideration of whether Bob’s dose of antidepressant requires adjustment

- follow-up options, including the use of telehealth.

Case 2

Linda, aged 20 years, presents to you requesting sleeping tablets for insomnia, which she has experienced for the past few months. She was made redundant from her job at a local cinema where she was working to support herself as a musician, but all her shows were cancelled. She has a supportive family who are helping her apply for other jobs. She denies any suicidal ideation or thoughts of self-harm. Options for management include:

- discussion about the importance of sleep hygiene and routine in sleep. Linda can be referred to the Head to Health website to access the ‘Managing insomnia course’ or the ‘Recharge app’, which is a six-week wellbeing course that focuses on improving sleep habits

- trialling the 3Cs approach. Control can be fostered by encouraging Linda to focus on things she can do now to help with her short- and long-term goals. Linda can be directed to mindfulness apps, which may help her find coherence by acceptance-based practice of observing and engaging in the present in a non-judgemental and non-reactive manner. Linda can even start a virtual concert with fellow musicians to facilitate connectedness among her peers

- consideration of social prescribing (eg focusing on her music, walking groups with friends or volunteering to help with elderly residents in the community)

- discussion about the importance of healthy lifestyle interventions and encouraging mindful engagement in activities

- referral to the Beyond Blue website for more information and resources

- discussion and supports around any negative coping strategies

- referral to the NewAccess program for mental health coaching.

Conclusion

Despite the various disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, most Australians are resilient and will not experience a diagnosable mental health condition. Feelings of fear and anxiety should not necessarily be considered pathological or require intervention; however, many others will have experienced an exacerbation of mental health concerns or developed a mental health condition for the first time. The management approach outlined in this article focuses on fostering resilience and promoting healthful lifestyle behaviours, psychological interventions and appropriate pharmacotherapy and referral. While this overview draws on online and application-based resources, the list of resources is not exhaustive, and clinicians have many options available to them to manage their patients’ mental health in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key points

- GPs are well placed to manage mental health issues in the context of a pandemic.

- Anxiety, loneliness and sadness are normal responses to a pandemic and are not necessarily diagnostic of mental illness.

- Strategies, such as strengths-based CBT and social prescribing, can be used to foster resilience in people with mental illness who are experiencing social isolation.

- Lifestyle recommendations should include physical activity, healthy eating, reducing stress, strengthening social supports and promoting functioning in daily activities.

- Psychological interventions have been delivered remotely with favourable results.