Recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs) are a clinical challenge for all involved in the care of the paediatric patient, with 8.4% of girls and 1.7% of boys diagnosed with a urinary tract infection (UTI) within the first six years of life.1 Up to 30% of these children will experience at least one recurrence within 6–12 months.2,3 While 3–15% of children with a first UTI will show renal parenchymal scarring within 1–2 years of their first UTI,4–7 the risk of acquired chronic kidney disease remains low.5,8

An rUTI can be defined as a repeated presentation with separate episodes of cystitis, pyelonephritis or urosepsis.

Vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) is one of a myriad of structural abnormalities that may increase the risk of rUTIs, affecting up to 40% of children who have had a UTI.9 It is important to recognise that in a third of paediatric patients, a UTI can be the initial symptom of urinary tract anatomical variation or other concomitant pathology.3

Understanding the cause of rUTIs is crucial for determining whether a conservative or invasive approach is most appropriate.10

The scope of this article is to review the various causes of rUTIs and management strategies ranging from conservative to surgical, with the aim of increasing clinician confidence in the primary care setting. There will also be an emphasis on VUR and bowel and bladder dysfunction (BBD) as they relate specifically to rUTIs.

Pathogenesis of recurrent urinary tract infections

UTIs are secondary to ascending periurethral colonisation from uropathogens, with Escherichia coli accounting for over 75% of cases. Other bacteria such as Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Enterococcus spp., Citrobacter spp. or Staphylococcus aureus may also be causative agents. Less commonly, fungal infections (eg candidiasis) and viral pathogens (eg adenovirus, BK virus) may be involved.10

These pathogens may cause lower tract disease (eg cystitis, prostatitis), upper tract illness (pyelonephritis, abscess) or systemic illness (urosepsis). UTIs can thus be classified by anatomical position, severity, symptoms or episode.

Diagnosis of recurrent urinary tract infections

Diagnosis of UTI in children is guided by a targeted history and examination, with investigations especially important in infants and non-verbal patients in order to exclude other differentials (Table 1).11,12

| Table 1. Differential diagnoses for urinary tract infection11,12 |

| Differential diagnosis |

Associated clinical features |

| Vaginitis |

Vaginal discharge, odour, pruritus. There is no frequency or urgency. |

| Vulvovaginitis |

Can cause dysuria and may co-exist with UTIs. |

| Urethritis |

Urinalysis shows pyuria but no bacteria. |

| Urge syndrome |

Frequency of micturition, urgency, daytime wetting and nocturnal enuresis. |

| Painful bladder syndrome |

Dysuria, frequency, urgency without evidence of infection. |

| Pelvic inflammatory disorder |

Lower abdominal/pelvic pain, fever, cervical discharge and cervical motion tenderness. |

| Prostatitis |

Tender prostate and pain on ejaculation. May be associated with or as a result of a concurrent UTI. |

| Sepsis or bacteraemia |

Fever, malaise, anorexia, lethargy. Non-verbal children and infants may present with similar symptoms for UTI as for sepsis. Early recognition and treatment of sepsis is critical. |

| UTI, urinary tract infection |

Dysuria, urgency, frequency, abdominal/flank pain or incontinence can be reported by verbal children or their carers. As a result of non-specific presentations of fever and general distress in infants, it is important to consider UTI as part of the differential diagnosis.5,13

A febrile infant younger than three months of age should be promptly managed in accordance with local guidelines,14 which in certain circumstances may recommend management on the basis of clinical suspicion without awaiting confirmatory testing.

A range of options exist for the collection of a urine specimen from a child (Table 2). It is important to consider not only the quickest or simplest collection method, but also one that will yield the cleanest sample free of contaminants.5,13

| Table 2. Options for the collection of urine specimens from paediatric patients5,10,13,37 |

| |

Clean catch/midstream urine |

Urethral catheterisation |

Suprapubic aspiration |

| Procedure |

Midstream urine caught in a clean specimen pot.

In infants or non-verbal children, stimulation of the cutaneous voiding reflex by wiping the perigenital area with a cold, damp gauze may also be used to achieve a sample. |

Collection of urine via ‘in and out’ catheterisation.

Thorough cleaning and aseptic non-touch technique must be used to minimise contamination and reduce risk of subsequent infection. |

Collection of urine via ultrasound-guided needle aspiration.

Must be performed with a full bladder (>20 mL), with the child on their back and restrained by the caregiver.

Light sedation may be required. |

| Indication |

Continent or older children able to follow instructions and indicate when they are experiencing urinary urge.

First-line non-invasive measure in pre-continent children and infants where there is good parental cooperation and rapport. |

Infants and pre-continent children.

Children unable to provide a clean catch sample.

Acute urinary retention. |

Infants.

Uncircumcised boys where adequate foreskin retraction is not possible.

Girls with labial adhesions.

Cases of periurethral irritation. |

| Benefits |

Non-invasive.

Minimal contamination. |

May be less painful and invasive than suprapubic aspiration.

Effective in urinary retention. |

Preferred method of aseptic collection.

With appropriate technique, provides a sample with minimal contamination.

Relatively quick procedure provided patient has a full bladder. |

| Disadvantages |

Reliant on child and caregiver cooperation.

May be time-consuming. |

Invasive and poorly tolerated.

Risk of iatrogenic introduction of uropathogens. |

Invasive and painful.

May be poorly tolerated by older children or caregivers.

May require sedation. |

To diagnose a UTI, suspicion of infection must be clinically correlated to both of the following criteria:13

- urinalysis suggesting pyuria and/or bacteriuria

- a urine culture of a uropathogen with at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) per millilitre.

Urine specimen collection should therefore be performed during each episode where there is clinical suspicion of a UTI, or intent to treat it as such.

An rUTI in children is diagnosed on the basis of the following criteria:15

- two or more episodes of acute pyelonephritis

- one episode of acute pyelonephritis and one episode of cystitis

- three or more episodes of cystitis.

The range of predisposing factors associated with rUTIs is illustrated in Table 3.10,12,13,16

| Table 3. Factors that increase risk of urinary tract infections10,12,13,16 |

| Virulence factors |

Concurrent illness |

Anatomical, causing stasis of urine |

Functional |

Behavioural |

- Resistance in uropathogens

- Incomplete or inappropriate treatment of prior episodes

- Immunosuppressed host

- Colonisation of indwelling catheter

|

- Gastroenteritis or diarrhoeal illness increasing periurethral spread of coliforms

- Dehydration leading to reduced voiding frequency and increased stasis

- Vaginitis or vulvovaginitis

- Candidiasis (genital thrush)

- Concurrent bacteraemia

|

- Vesicoureteric reflux (primary or secondary)

- Posterior urethral valves

- Phimosis

- Other obstructive uropathy (any level), including urolithiasis

- Congenital abnormalities of the kidney and ureteric tract

|

- Bowel and bladder dysfunction including constipation

- Other neurogenic bladder causes

|

- Sexual intercourse

- Encopresis

- Periurethral colonisation secondary to poor hygiene practices

|

Management of recurrent urinary tract infections

Successful management of rUTIs requires collaboration between the children, caretakers and healthcare professionals.17 Referral to a paediatric service for review should be considered where appropriate. Education should be provided to carers such that in future febrile illnesses, prompt medical evaluation should occur to ensure that rUTIs are managed in a timely manner.13

Acute management

Following investigation, appropriate choice of antibiotics should be made on the basis of local sensitivities, guidelines and growth sensitivities in previous UTIs.18–20 The decision for oral administration of antibiotics should consider the patient’s age, risk of urosepsis, compliance with oral management, and other clinical factors (vomiting, diarrhoea).21,22 Where necessary, parenteral therapy should be given. Repeat imaging and monitoring of renal function should be considered, especially in those with rUTIs.

Referral

Referral to the local tertiary service for consultation should be contemplated in children aged <6 months, children with evidence of sepsis or shock, and those who require care beyond the capacity of their local services.22,23 Based on local service availability and guidelines, referral can be to a paediatrician, paediatric urologist or, in some cases, the local urology service.

Prevention

Hygiene practices

Children and caregivers should be educated on hygiene practices that minimise bacterial burden.18 Education on perineal care including wiping (dabbing or front-to-back) post–bowel motions23 and appropriate washing of the glans and foreskin in uncircumcised boys may assist in prevention of uropathogen colonisation.18

Avoidance of bubble baths, which can cause mucosal irritation and genital discomfort, is recommended to decrease mimics of an impending UTI.5

Parents can refer to several resources when learning about good hygiene practices for children, namely Raising Children Network (https://raisingchildren.net.au)24 and The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCH), which provide information regarding penis and foreskin care.25 The RCH also provides information regarding vulval skin care for both children26 and adolescents.27

Conservative (non-antibiotic) prevention

Probiotics have garnered much attention in their possible role to prevent rUTIs, despite little current evidence to suggest usage.28–30

Cranberry products, although safe, are poorly tolerated and may only confer a benefit in patients with normal anatomy.15,28 Research on the topic has been conflicting and often of low quality.31

The identification and management of disorders such as VUR and BBD is important for preventing UTIs in these patient groups, and further detailed later in this article.

Antibiotic prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections

Extensive studies into the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis of UTIs have shown no evidence to suggest initiation from the index UTI. Given the likelihood of developing resistance, it is recommended that a paediatric specialist be involved in the decision to initiate long-term antibiotic prophylaxis. Additionally, continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) therapy is associated with adverse effects in 8–10% of cases, with most being non-serious reactions including nausea, vomiting and skin reactions.32

Overall, CAP should be considered in high-risk populations that are susceptible to rUTIs and at risk of renal damage.5,21 Patients with both VUR and BBD are at the highest risk of rUTI5,33 and may benefit most from CAP.34 The antimicrobial options for CAP are included in Table 4.35,36

| Table 4. Agents used in continuous antibiotic prophylaxis35,36 |

| Antibiotic regimens |

Dosage and administration |

Common side effects |

Practice notes |

Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole

(age >1 month) |

- 2 + 10 mg/kg up to 80 + 400 mg

- Orally

- At night

|

- Fever

- Gastrointestinal upset: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, anorexia

- Rash or itch

- Sore mouth

- Hyperkalaemia

- Thrombocytopaenia

|

- Contraindications: preterm infants, infants <6 weeks of age, megaloblastic anaemia, HIV, SLE, concurrent treatment with oral typhoid vaccine, renal impairment, severe liver disease

- Monitoring required during long-term therapy:

- Full blood examination

- Folate levels

- Serum potassium

|

| Trimethoprim |

- 2 mg/kg up to 150 mg

- Orally

- At night

|

- Fever

- Gastrointestinal upset: nausea, vomiting

- Rash or itch

- Hyperkalaemia

|

- Contraindications: megaloblastic anaemia, folate deficiency, renal impairment

- Monitoring required during long-term therapy:

- Full blood examination

- Folate levels

- Serum potassium

|

| Cefalexin |

- 12.5 mg/kg up to 250 mg

- Orally

- At night

|

- Gastrointestinal upset: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea

- Opportunistic infection: Clostridium difficile, Candidiasis, Enterococcus spp.

- Rash

- Headache

- If injected: pain and inflammation at the injection site

|

- Contraindications: severe hypersensitivity to penicillins or carbapenems may lead to cross-reactivity

- Monitoring required during long-term therapy:

- Full blood examination

- Renal function

|

Nitrofurantoin

(age >1 month) |

- 1 mg/kg up to 50 mg

- Orally

- At night

|

- Gastrointestinal upset: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, anorexia, abdominal pain

- Allergic skin reactions

- Headache

|

- Contraindications: renal impairment

- Monitoring required during long-term therapy:

- Pulmonary function

- Three-monthly liver function testing

- Renal function

|

| HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus |

Surgical management of recurrent urinary tract infections

While the majority of rUTIs respond to conservative or pharmacological management, in a small subset of boys with rUTIs, surgical management may be recommended.37–39 In uncircumcised boys <1 year of age with rUTIs or grades III–V VUR, circumcision can be considered on the basis of the child’s baseline risk and foreskin anatomy.28,39 In this particular age group, the risk of UTI and rUTI is highest when compared with older children, girls of the same age and uncircumcised infant boys, with studies also suggesting an increased risk of complications and renal scarring following UTI. Thus, circumcision is weighed against non-invasive measures, with a greater benefit in infants aged <1 year.38 The decision to proceed to circumcision should be accompanied by a thorough discussion between parents, the primary care physician and specialist services.39

Recurrent urinary tract infections in high-risk patient populations

Vesicoureteric reflux

Definition

VUR is a common anatomical anomaly in children.21 It is often diagnosed following investigation of a UTI, as approximately 30% of children with UTIs will be diagnosed with VUR.40 Recurrence will affect 20–30% of children diagnosed with VUR.40

VUR is the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder to the kidney due to a dysfunctional vesicoureteric junction (VUJ).41 It can be both an anatomical and functional disorder, influenced by anatomical changes in the intramural ureter, ureteric opening width and function of trigone and ureteric muscles.40 VUR is associated with developing renal scarring, renal hypertension or chronic end-stage kidney disease.17

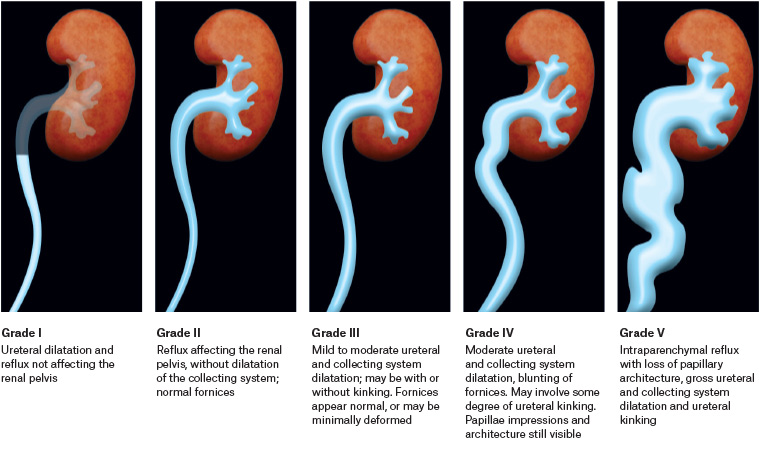

VUR severity is graded on the basis of the height of retrograde flow, dilation and tortuosity of the ureters.40 The five different categories of VUR severity are described in Figure 1.21,42

Figure 1. Appearance of vesicoureteric reflux on voiding cystourethrography.21,42 Click here to enlarge

Diagnosis

Investigation of suspected VUR should begin with simple ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (KUB), which will assess the renal parenchyma for scarring or anatomical abnormalities43 and may have a role in diagnosing low-grade (I–III) disease.44

After completing routine investigations, the child should be referred to a paediatric specialist, who may choose to complete further and more invasive testing.45

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is the gold-standard investigation for VUR, indicated in rUTIs, a first febrile UTI and/or an abnormal renal ultrasound.28,46,47 A dimercaptosuccinic acid nuclear scan can also be performed to assess renal scar formation as it is considered the gold standard.10

Grading of VUR on VCUG is directly linked to decision making regarding treatment in a specialised setting. Understanding of this can be used to support patients and their families/caregivers (Figure 1).

Management

Once VUR is confirmed, the approach to management is contingent on the grade of VUR, presence of febrile UTI, age and sex of the patient and presence of bladder or bowel dysfunction.48

Management options include surveillance, CAP and various surgical interventions.49 Typically, young age (ie <1 year) and low-grade VUR (I–III) are favourable for spontaneous resolution and therefore do not require surgical intervention if uncomplicated.21,49

There has been significant debate regarding the use of CAP.48 The benefit derived is typically dependent on several factors including age, severity of VUR, presence of BBD, toilet training and circumcision status.49

In several studies, CAP was found to significantly reduce the number of rUTIs in VUR grade ≥III; however, prevention of renal scarring was not a statistically significant outcome.50,51 Studies demonstrate mild support for CAP in low-grade reflux.21

Surgical treatment is recommended in patients with high-grade VUR (≥IV), ineffective or poorly tolerated CAP or evidence of renal damage. It is the quickest solution for VUR; however, there is no evidence supporting reduced renal scarring.33 Options for management include open surgery (gold standard), endoscopic treatment and robot-assisted laparoscopic ureteral implantation.34

Bowel and bladder dysfunction

Definition

BBD, previously known as dysfunctional elimination syndrome, is associated with an increased risk of rUTIs. BBD is characterised by a set of lower urinary tract and bowel symptoms such as urgency, withholding manoeuvres, daytime urinary incontinence, constipation and painful defecation.28,52 Despite being a risk factor for rUTIs and worsened in the setting of VUR,1 BBD is a common urological paediatric complaint often under-recognised and under-treated in the primary care setting.28,53 Neurogenic disorders (eg spina bifida) can cause dysfunctional voiding, which falls into the BBD spectrum due to failure of relaxation of the urethral sphincter during voiding.53

Diagnosis

Evaluation of BBD is made through clinical history, physical examination, and bladder and bowel diaries.53 Tools such as the Bristol stool chart or validated screening questionnaires such as the Dysfunctional Voiding Score System and Vancouver Symptom Score can assist in diagnosis and ongoing management.28,52,53

Management

The conservative management of BBD consists of timed voiding, pelvic floor awareness and training, hydration, and constipation treatment or prevention.53 Approximately half of patients will improve with conservative treatment alone.53

Pharmacological management, such as anticholinergic or selective α-blockers, if indicated for certain symptoms, may be considered.53 It is recommended that patients refractory to conservative management be referred to a paediatrician for appropriate investigation and management of underlying anatomical or neurological abnormalities.53,54

Conclusion

Unique management challenges are posed by rUTIs in the primary care setting. Conservative measures such as hygiene, bowel and bladder education confer a significant benefit, while long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is poorly tolerated, exposes children to adverse effects and increases the likelihood of bacterial resistance.

Referral to specialist paediatric or urology services should be considered in situations where the care needs exceed the capacity of the health service, in children younger than six months of age or in cases of urosepsis or shock.

An important consideration in the management of paediatric rUTIs is the diagnosis of aberrant anatomy, VUR or BBD. Management of these patient populations follows the same progression of conservative to invasive management, and consideration must be given to the natural resolution of symptoms with age. BBD is under-recognised and under-treated despite management options being readily available in the primary care setting.

Key points

- Up to 30% of paediatric patients (aged <6 years) will have recurrence of UTIs.

- Children with VUR and BBD are two paediatric groups that commonly experience rUTIs.

- Successful management of rUTIs requires collaboration between the children, caretakers and healthcare professionals.

- Management of rUTIs includes conservative, alternative, antibiotics and surgical paths.

- Referral to specialist paediatric services should be considered if there are any concerns.