Pia Bradshaw (pictured) is Autistic and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and an autism health researcher and PhD student in Medical Sciences, and Claire Pickett is an Autistic general practitioner.

Many general practitioners (GPs) have not received training on autism spectrum condition (hereafter ‘autism’),1–3 and even if they have, it is likely there are still areas in which they would like further training or do not feel confident.

It is estimated that one in 59 people is on the autism spectrum;4 therefore, Autistic adults, whether formally diagnosed or not, will at some point attend general practice. Studies show GPs self-report low levels of confidence in treating Autistic patients and adapting their practice to meet the needs of these patients.3 GPs most commonly report low confidence in communicating with Autistic patients, performing physical examinations or procedures, and accurately diagnosing and treating other medical issues. Additionally, GPs have low confidence in helping patients remain calm and comfortable during consultations, identifying accommodation needs and making changes to accommodate such needs.5

While knowledge of autism has improved, stigma, stereotypes and misinformation remain.

It was not long ago that the increasing number of autism diagnoses was described as an ‘epidemic’.6–8 Nowadays, the increase in prevalence rates is attributed to better understanding of the condition and a greater ability to identify and diagnose it, among other factors. This is certainly the case with many adults, particularly females, who were overlooked in childhood and received an autism diagnosis later in life, as was the case of the primary author of this article, who was diagnosed at the age of 30 years. However, the common misconception that autism ‘looks’ a particular, outwardly obvious way remains a significant barrier to accessing and receiving an autism diagnosis. It is widely understood among the Autistic community that GPs, psychiatrists, psychologists and autism ‘experts’ often conflate autism with intellectual disability, which is an entirely separate condition; only 30% of Autistic people have a co-occurring intellectual disability.4

The longstanding myth that autism is a condition that mainly affects children is apparent in the lack of available supports and services for Autistic adults. Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental difference, and Autistic children grow into Autistic adults. Many females who go on to receive an autism diagnosis in adulthood are initially overlooked, dismissed, not believed or misdiagnosed,9,10 as was the case of the primary author of this article. This may be because they often do not clearly meet current diagnostic criteria, which are modelled on the experiences of male children. They may have different interests to the male stereotype (eg trains, timetables, numbers), such as reading fiction, creative writing, makeup, video games or true crime. Previous prevalence estimates of four males to every one female have been determined to be closer to 3:1, and as close as 2:1 for those with an accompanying intellectual disability.11

Autistic adults report social camouflaging or masking their authentic Autistic behaviours to avoid standing out or having their differences draw attention.12,13 Camouflaging or masking is used to compensate for aspects of social interaction that do not come naturally to hide one’s authentic Autistic behaviours.14 Authentic Autistic behaviours include expressing themselves freely without shame or reproach, and self-stimulatory behaviour (known as ‘stimming’) such as singing, dancing, making noises, repeating phrases from TV or movies (known as ‘echolalia’).15

As a result of common misconceptions, stereotypes and misinformation about autism, some Autistic people are cautious about or avoid disclosing their diagnosis to healthcare providers, employers, landlords and friends or family in fear of discrimination or because of previous negative experiences with disclosing their diagnosis.16

The aim of this viewpoint article is to:

- introduce basic concepts about autism and challenge stereotypes

- introduce neurodiversity and autism from the perspective of two Autistic adults – PB is Autistic and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and an autism health researcher and PhD student in Medical Sciences, and CP is an Autistic GP

- provide background knowledge to respectfully engage with Autistic individuals.

A paradigm challenging medical models: Neurodiversity

The Autistic community has adopted the neurodiversity paradigm, which accepts the biological fact of neurological diversity among humans and the view that no one type is more valid, healthy or right than another.17 It challenges the prevailing notion of pathologising neurodiverse brains, and it instead views diversity through the lens of a social model of disability whereby societal barriers are key factors that disable people.18 The Autistic community applies the concept of neurodiversity to how autism is viewed, and challenges the dominant assumption that autism is a disease or disorder and should be eradicated, prevented, treated or cured.17,19–21 An analogy to describe autism is: just because a PlayStation cannot read an Xbox game does not mean it is broken or has a processing error – it is just a different operating system.

Conceptualising autism as linear and binary is a misnomer

The autism spectrum is often conceptualised as a linear concept using high- or low-functioning labels and understood as something whereby an individual would experience autism either mildly or severely.22,23 Although ‘high-functioning autism’ is not a formal diagnosis,24,25 its erroneous continued use among health professionals and autism researchers has made it synonymous with expectations of better functional skills and long-term outcomes despite contradictory clinical observations.22

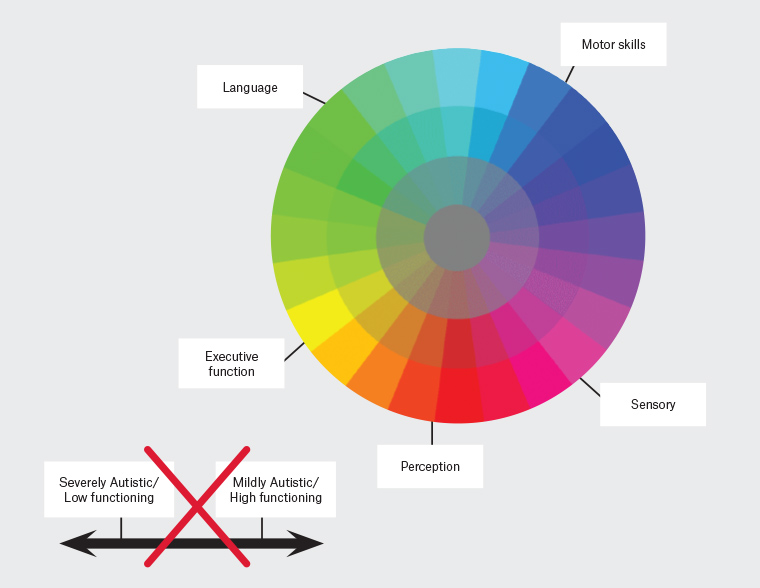

Classifying Autistic people into levels and using high- and low-functioning labels fails to capture the critical fact that autism is not static, but rather fluid in nature (Figure 1).26 The skills and capabilities of an Autistic person will develop throughout their lifespan. Therefore, it is unlikely that health professionals can predict the long-term outcomes and capabilities of Autistic people with any certainty. Alternatively, learning from the lived experiences of Autistic adults provides invaluable insight into the neurobiological responses that shape the behaviours and the strengths and challenges of Autistic people.

Figure 1. An example of a correct (spectrum colour wheel) and incorrect (linear) way to view the autism spectrum

Additionally, functioning labels fail to capture the varying day-to-day capacity of Autistic people’s ability to respond to and manage the demands and responsibilities of adulthood when faced with sensory stimuli, environmental stressors, communicative differences and health challenges. Using autism levels and functioning labels overlooks the real challenges and barriers of Autistic people who may not outwardly appear different, and minimises the strengths, abilities and capacities of those who do.

The continued classification of autism levels and functioning labels by health professionals, autism researchers and broader society counters efforts to better educate people with an updated knowledge of scientific research, and be equipped with the necessary skills to meet the needs of Autistic patients. Indeed, the use of such terminology is harmful to Autistic people, their supporters and/or loved ones because it reinforces the stigma, myths and misinformation that create barriers for Autistic people and prevents the acceptance of Autistic people within society.

As Adam Walton, an Autistic self-advocate, says so eloquently:27

[So-called] mild autism doesn’t mean one experiences autism mildly … It means YOU experience their autism mildly.

Autism should be viewed as a spectrum condition comprising different language, sensory, executive function, perception and motor skills, whereby every Autistic person possesses a unique profile with varying degrees of strengths and challenges in each category; this profile is fluid across the lifespan (Figure 1). Language should focus on specific support needs rather than ‘severity’.

There’s an expression, ‘If you’ve met one Autistic person, you’ve met one Autistic person’. This expression reflects the unique and varied nature of autism because no two Autistic people are the same. They may share similar traits, but ultimately their cognitive profiles (eg executive functioning, language, perception etc) will determine where their strengths lie and what areas are challenging and require additional supports.

Why the way we talk about autism matters

It is imperative for health professionals, and broader society, to listen to and understand the experiences of Autistic people to then understand the reasoning behind the language and terms used to describe them in a respectful manner.

Health professionals tend to use ‘with autism’ because they are taught to use person-first language during their training. Traditionally, person-first language, which is the recognition of the person first and that any condition or disability is secondary to their identity, has been the dominant language to use when discussing disability. However, when discussing autism, the Autistic community advocates for the use of identity-first language. An Autistic brain cannot be separated from an Autistic person as it defines the way in which they perceive the world. A deaf person is not described as someone with ‘deafness’ – they are ‘deaf’. The Autistic community does not see themselves as disordered and is proud of their neurology. Despite this, in the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, autism is still coded as ‘autism spectrum disorder’, and the International classification of diseases, 11th revision, groups autism under ‘pervasive developmental disorders’, so the of use ‘disordered’ terminology will appear in formal diagnoses, reports and services.24,25,28 However, not all Autistic people will use the same language and terms (a small proportion of Autistic people may use ‘with autism’), and some may use the language of their diagnosis, so it is always best to ask the patient their personal preference.

Until recently, the narrative of autism has been shaped without the voices of Autistic people themselves; as a result, important aspects are missing. The understanding of the reasoning, emotions and behaviours of Autistic people, and how they experience and perceive themselves and this world, are all explained through the lens of a non-Autistic person. Non-Autistic interpretations of autism are narrow and limited, as non-Autistic people do not have the ability to see, experience and ultimately understand autism to the same extent as Autistic people do through their lived experience. Likewise, although non-Autistic people provide important contributions and supports to Autistic people (eg scientific advancements about the brain, and the important roles relatives, supporters and/or friends have), the Autistic community needs greater involvement in the priority setting of autism research to ensure outcomes and resources reflect their needs and can provide the greatest impact.28

Health professionals have a responsibility to consider the effect of their attitudes and words on parents of newly diagnosed children, family members, newly diagnosed Autistic people of any age and supporters who seek information and support. Speaking to an Autistic patient/family using deficits-based language that infers that autism is attached to what would be an otherwise healthy brain teaches people to view themselves or their loved one as broken, a burden and someone/something to be endured or fixed. This perpetuates an erroneous and unhelpful narrative to Autistic individuals, parents and supporters as well as the Autistic community’s efforts to better educate society about autism and promote autism acceptance. Healthcare workers are trusted authorities who can counter stereotypical viewpoints and narratives that reinforce stigma.

GPs should use language that reflects autism acceptance, focused on building on an individual’s strengths instead of their deficits and and supporting self-acceptance.29 This is not to dismiss the very real and often challenging factors that disable Autistic people, such as living within a predominantly non-Autistic society that is often not accepting or accommodating to people who are different. Instead, GPs and broader society need to acknowledge ableism (ie beliefs and practices that discriminate against disabled people) and reflect on how autism is thought about. It is important to reconsider the ways in which autism is spoken about to ensure Autistic people are treated with dignity; their experiences, preferred language and identity are respected; and a culture of autism acceptance is promoted (Tables 1 and 2).

| Table 1. Ableist terms, language and topics to avoid and use when discussing autism23 |

| Terminology to avoid |

Preferred terminology |

| With autism |

Autistic |

| Disorder[ed] |

Difference |

| [Ab]Normal |

Different/difference/Autistic/non-Autistic |

| Suffer[ing] |

Experience, impact, effect, challenges |

| High/low functioning or mild/severe |

Describe specific strengths and needs (ie working memory, motor skills, executive function, etc) and specific areas where substantial or minimal support is needed |

| Retarded |

Disabled, Autistic, neurodiverse/neurodivergent |

| At risk of autism spectrum disorder |

Increased likelihood/chance of autism |

| Fix/cure[autism]/‘optimal outcome’ |

Discussions focusing on quality-of-life outcomes |

| Comorbid |

Co-occurring |

| Non-verbal |

Non-speaking/partially verbal |

| Affected |

Autistic person |

| Intervention/some ‘social skills training’ |

Support, embracing Autistic identity and prioritising happiness and mental health |

| Treatment |

Support or services |

| [Autism] symptoms |

Be specific about Autistic characteristics, features or traits |

| Challenging/problematic/disruptive/problem behaviour/tantrum |

[Autistic] meltdown |

| Special interest(s) |

Areas of interest |

| Special needs |

Specific description of needs and disabilities |

| Table 2. Things to avoid saying to an Autistic person |

| Avoid saying to an Autistic person |

Explanation |

| You don’t look Autistic/You’re not Autistic |

Autism is an invisible condition and does not look any particular way. |

| You must be very high/low functioning |

The autism spectrum is not linear; functioning labels overlook and underestimate people’s individual challenges, disability and strengths. |

| Everyone’s/We’re all a little bit on the spectrum/Autistic |

Non-Autistic people may share similar traits to Autistic people, but being officially diagnosed as Autistic means fulfilling all the specific criteria for diagnosis of the condition. |

| I know about autism because my [relative/friend] has it |

All Autistic people experience their autism differently from one another. Knowing someone who is Autistic does not translate to an understanding of autism, or the specific way that person experiences their autism. Never assume, and always listen. |

Conclusion

It is likely that GPs will see Autistic patients in their general practices. It is necessary to be up to date with knowledge and language about autism, as society’s understanding of autism is continuingly being refined and informed by the Autistic community. It is important to shift away from a linear understanding of autism and move towards a spectrum approach. The use of functioning labels and classification of autism into levels can be harmful and discount the very real challenges Autistic people experience, negating any fluidity across the lifespan and even an individual’s day-to-day capacity. Lastly, as a profession, it is critical to change the way autism is talked about, shifting towards identify-first and respectful language that does not see autism as a burden or disease to cure but an accepted and valued part of our species’ neurodiversity.

Key points

- Stereotypes, stigma, myths and misinformation about autism persist, resulting in poor healthcare experiences.

- Functioning labels are harmful and do not capture the full and fluid nature of autism.

- Language preferences of Autistic patients and the Autistic community should be used when referring to autism.

- It is important to avoid using ableist, deficits-based and pathologising language in relation to autism.