Bowel cancer is a preventable chronic condition, with one in 13 people developing the disease by the age of 85 years.1 It is Australia’s third most common cancer after prostate and breast cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in Australia, after lung cancer.1 Bowel cancer incidence and mortality rates are especially high for people residing in outer regional and remote areas of Australia.2 Tasmania has the highest age-standardised bowel cancer incidence rates of all states, and the second highest mortality rates after Northern Territory.2

Early detection of bowel cancer has been associated with better health outcomes, including a five-year survival rate of up to 99% for stage 1 cancers.3 However, current Tasmanian participation rates in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) sit just below 47%.2 This is despite being a well-funded, comprehensive, public health program.

Potential reasons for low participation include procrastination,4 lack of knowledge,5 perceived low personal value of the test,6 fear of cancer5,7 and ambivalence.7 In contrast, enablers for those who do screen include higher income and education,8 and having known someone with bowel cancer.9

General practitioners (GPs) have also been reported to play an important role in increasing bowel cancer screening rates. A 2017 review found GP recommendation, provision of information and the supply of a faecal occult blood test kit (FOBT) to patients all contributed to increased screening participation.10

Unfortunately, patient access to GPs in rural Tasmania can be difficult because of persistent workforce shortages in these areas,11 limiting GPs’ ability to encourage bowel cancer screening in their patients.

In this context, we aimed to identify the enablers and barriers to bowel cancer screening in outer regional and remote Tasmanian communities from the perspective of GPs working in these areas, to develop recommendations for increasing bowel cancer screening rates.

Methods

Approach

A qualitative approach was used to identify influences on NBCSP uptake in three outer regional and one remote Tasmanian Local Government Area (LGA). LGAs with varying participation rates ranging from high to low (Latrobe 47.3%, Break O’Day 41.6%, George Town 41.6% and West Coast 34.3%), relative to the state participation rate of 44.3%,12 were chosen in order to achieve a good cross-section of responses (Appendix 1, available online only).

Community members and health professionals (including GPs) were invited to share their views on the reasons for the current participation rates in their LGA, and suggestions for improving NBCSP uptake. Fifty community members and 28 health professionals were interviewed. Given the GP voice is not well represented in the bowel cancer screening research literature, this study reports on the GP interview data only.

Setting and sampling strategy

Nine general practices were based within the four targeted LGAs. A convenience sample of one practice per LGA was sought. All GPs working in each of the four practices were invited via email to participate in the study through their respective practice managers. Eight GPs agreed to participate (29% response rate); four were male and four were female. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection techniques

Face-to-face interviews were conducted in each practice. The interviews obtained participants’ views about NBCSP participation rates within their community, as well as ideas for improving participation rates overall. A predetermined schedule of open-ended questions was used to guide the interviews and further information was elucidated depending on the GPs’ responses. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim using a professional transcribing service. Transcripts were anonymised and each participant was given a code number. All transcripts were reviewed for accuracy.

Reflexivity

One of the study’s authors has a background in bowel cancer screening research, while another has a background in community pharmacy. While these backgrounds were useful in understanding participant responses throughout the interviews and helped to detect items of significance during data analysis, both researchers made conscious efforts not to accept common assumptions at face value by clarifying all responses with the GPs. Neither of the interviewing authors were known to the participants of this study.

Analysis

To meet trustworthiness criteria for qualitative research,13 data were analysed using a six-phase thematic analysis approach developed by Nowell et al.14 Three researchers worked independently and as a team to familiarise themselves with the data, generate initial codes, search for themes, review themes, define and name themes, and produce the results. Analysis was conducted using NVivo 12 (QSR International). The derived themes were then categorised as either barriers or enablers for participation in the NBCSP, and further aligned to Fleuren’s theoretical framework for determinants of innovation within healthcare organisations (Table 1).15 The four key determinants comprised characteristics of the end user (eg patient knowledge, attitudes, beliefs); organisation (eg general practice/GP workload, staffing issues); health innovation (eg complexity or relative advantage of the NBCSP/kit); and sociopolitical context (eg broader health system, community characteristics).

| Table 1. GP-identified barriers and enablers for NBCSP participation in rural Tasmania |

| Barriers |

Patient |

GP/practice |

Innovation (NBCSP) |

Sociopolitical context |

Low literacy/health literacy

- Patient thinks they are healthy and does not need checks

- Patient does not initiate bowel screening conversation with GP

- Patient is seen to have poor literacy/health literacy

Negative health beliefs, perceptions and attitudes

- Apathy

- Denial

- Fear of bowel cancer

- Fear of colonoscopy

- Fear of seeing doctor

- Anxiety waiting on results

- Patient does not see the importance

- Patient perceives kit as difficult

- Distrust of NBCSP kit

- Patient does not like dealing with faeces

|

Provision of different kits to patients

- GP provides different kit to patient

- GP prefers other kits

- GP uses own kit to ensure they receive the test result

General practice workforce challenges

- Busy GP

- Limited choice of GP in rural community

- Continuity of patient care is difficult to achieve because of high turnover of locums

|

Low/negative NBCSP profile

- Limited advertising for NBCSP

- Low and declining profile of NBCSP in community

- GP loss of confidence in kit

- GP is unfamiliar with the NBCSP kit

Limitations of NBCSP and kit

- GPs are not informed by government about the program

- GPs are not integral to NBCSP roll-out

- Issues with distribution

- Problems with the kit itself (eg paper falls in toilet)

|

Low community levels of health awareness

- Bowel cancer screening is less ingrained (when compared with other cancers)

- Low community awareness of bowel cancer prevalence

- Low public discussion of bowel cancer (when compared with breast cancer)

- Public misconceptions around bowel cancer

Social determinants of poor health

- Socioeconomically disadvantaged

- Low education levels

- Men less likely to do the test

- Itinerant population

- Long colonoscopy wait times in the public health system

|

|

Enablers

|

High health literacy/health awareness

- Patient understands the importance of screening

- Patient is seen to have good health literacy

Strong/trusting patient–GP relationship

- Same-gender GP is important when talking about bowels

- Patient trusts the GP

- Compliance is seen as high when GP gives patient FOBT kit

|

Proactive GP

- GP shows and explains FOBT kit to patient

- GP promotes screening as a positive health message for patients

- GP has a preventive health focus

- In-house bowel cancer screening reminder system – prompt on electronic patient files

- GP includes bowel as part of screening reminders for patients

|

High/positive NBCSP profile

- GPs are aware of NBCSP

- GP thinks kit is easy to use

- NBCSP results act as a reminder to GPs

- Receiving NBCSP results boosts GP confidence in the program

Timely colonoscopy

- GP recommends NBCSP over other kits because of fast-tracking for colonoscopy

- Performance targets and payments for hospitals that scope NBCSP patients

|

Community connectedness

- Connected community

- Consumers talk about bowel cancer

- High rate of cancer in community

- Small community/increased awareness within families

Social determinants of good health

- Higher socioeconomic status

- Highly educated people

- Older population/retirees

- Women are used to being screened for cancer

- Culture of farmers

|

| FOBT, faecal occult blood test kit; GP, general practitioner; NBCSP, National Bowel Cancer Screening Program |

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the Tasmanian Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee reference number H0016209. All participants provided informed consent before the interviews, which were transcribed by a professional transcribing service. Only two of the authors had access to the raw data.

Results

The interviews revealed a range of enablers and barriers to the uptake of bowel cancer screening in Tasmania. These were classified according to Fleuren’s framework (Table 1).

Patient-related barriers and enablers

Several barriers and enablers to bowel cancer screening were patient related. These included health literacy levels, health beliefs and patient–GP relationships. Health literacy levels were identified as both an enabler and barrier to bowel cancer screening. The GPs reported that patients who have reasonable health literacy levels understand the importance of screening and would likely participate. Conversely, many patients with low health literacy were viewed as less likely to understand the importance of screening and in turn would be less likely to use the NBCSP kit.

So here, fairly classically, a lot of people are low socioeconomic, low health literacy, and so they just don’t have the understanding of how important it is to be screening and how well the pick-up rate is for bowel cancer and polyps, and the importance of that.

The study also identified a range of individuals’ health beliefs, perceptions and attitudes that posed a barrier to bowel cancer screening uptake (Table 1). They included perceiving the kit as too difficult to use, apathy towards screening, distrust of the NBCSP kit and not wanting to deal with faeces. Fear was also seen as a common barrier in terms of receiving a diagnosis of bowel cancer, having a colonoscopy procedure or visiting a doctor.

And I think, you know, some of the rural communities where people are … there are some that are very phobic of doctors and they’ll only go to the doctor if they’re dying; particularly men.

The quality of patient–GP relationships came up strongly as a positive determinant of bowel cancer screening. The participants reported that patients were more likely to take part in bowel cancer screening if they had a good relationship with their GP and received the screening kit from them. Participants said that if this measure was put in place, they would have the opportunity to explain the procedure and the need for screening to their patients.

I think it’s quite different when it comes from us because they have that trust and understanding from us that they don’t get from the pack, whereas I think if there was some way of when you’re sending out the pack to people, we also got something to then be encouraging them to do it, it would be completely different.

GP/practice-related barriers and enablers

Several GP/practice-related barriers and enablers of bowel cancer screening were identified.

High workloads and time pressures meant that bowel cancer screening was often not seen as a high priority by GPs during a consultation. The large range of possible health screening activities meant GPs often had no extra time to discuss bowel cancer screening, or they sometimes forgot to ask patients about it.

But, then maybe, you know we do forget. You’ve got a million things you’re supposed to think about doing, check the blood pressure, ask them about their pap smears, check if they’ve had a mammogram, see if they’re, you know, whatever … you know, you could be spending a whole consultation on so many different things.

However, the interviews also suggested that proactive GPs may influence uptake of bowel cancer screening. Several reported actively promoting bowel cancer screening, including showing and explaining screening kits to their patient.

GPs have to mention it every time as part of their screening process. And I often say to people, you know, the best thing about bowel cancer is it’s one that we’ve got really good chances of catching and stopping and that’s … so, that’s kind of a positive thing instead of something to be scared about.

Program-related barriers and enablers

Several determinants identified in the study were directly related to the NBCSP. Declining public campaigns as well as a loss of confidence in the kit due to past false results were viewed as barriers to the uptake of bowel cancer screening.

Limitations of the program itself were reported, including not knowing when patients received a kit. Participants described how they were not part of the NBCSP and had not been well informed of the program by the government. As such, GPs felt they were limited in their ability to contribute to the success of the program.

No, you don’t know it’s coming … I’m happy to be a bit more motivated and tell people, and I know the government’s trying to do its thing, but it sort of cuts us out to a point really.

A positive aspect of the NBCSP program is that GPs sometimes prefer NBCSP kits over other kits because of fast-tracking for colonoscopy. Some GPs stated that patients who tested positive after using the NBCSP kit had a greater chance of having a colonoscopy conducted within 2–3 months when compared with those using other kits. Consequently, GPs were happy to encourage the use of the NBCSP kit.

And so they actually get it done quicker. So generally, if we’re sort of bordering on for someone and we go ‘if you’ve got one at home, do the one that you’ve got at home’ because it potentially can bump them up the list to get it done quicker.

Sociopolitical context

Low levels of health awareness and several social determinants of health were reported to influence the uptake of bowel cancer screening. Low education levels, itinerant populations, low community awareness of the prevalence of bowel cancer and low public discussion of bowel cancer were identified as reasons for low screening rates. Conversely, a high socioeconomic status, high level of education and high level of awareness were reported to be enablers for bowel cancer screening. The interviews also suggested that the awareness level of bowel cancer is high within a well-connected community and this also served as an enabler for bowel cancer screening:

It’s very much a community and everybody knows or is related to everybody else. I was sitting in the café just a short while ago with a friend who lives in the community and he knew everybody. Literally most everybody that walked past today, everyone says hello and they were from his work or wife’s work … So, they really do know everybody. And so, it only takes one or two people to have had a positive test that have survived bowel cancer when it will be well talked about ... And the family groups here, often they get together at some celebration and it’s 20, 30 people without a problem and that’s just family. And so, this information gets around. I think in that way, you were asking about the community’s knowledge; it may not be knowledge but it’s certainly – if there are cases (of bowel cancer) – then they’re known by the immediate family. And so that would make those people use the kit.

Suggestions for improving bowel cancer screening uptake

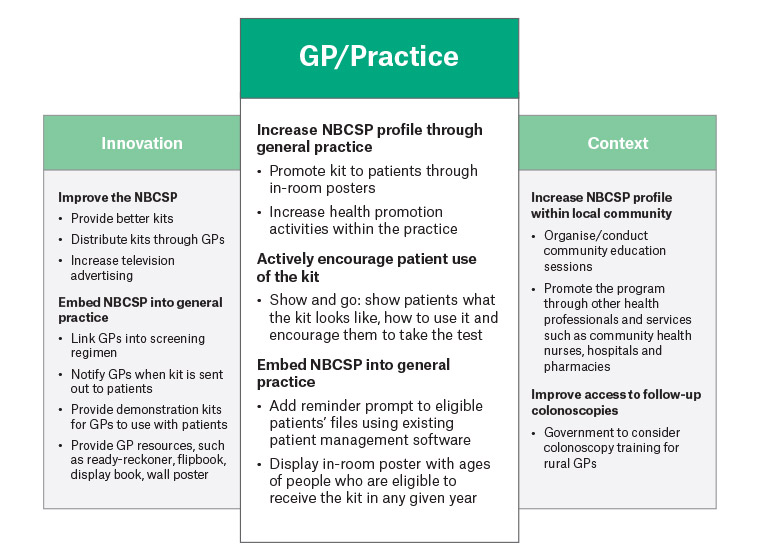

Many suggestions were provided by the informants on the best and most practical approaches to increase screening uptake. This included embedding the NBCSP into general practice care, promoting NBCSP profile through other health professionals, improving access to follow-up colonoscopy and increasing television advertising (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Identified opportunities for improving participation in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in rural Tasmanian communities: Thematic analysis of general practitioner interviews

GP, general practitioner; NBCSP, National Bowel Cancer Screening Program

Discussion

The NBCSP has been operating in Australia for more than 13 years, yet participation rates in the program remain low. Here we present the perspective of rural GPs on the barriers and enablers to patient participation in the NBCSP.

Rural GPs perceive the following as key enablers for patient participation in the NBCSP: having a good relationship with patients, proactively encouraging patients to screen for bowel cancer and having a professional preference for NBCSP kits because of fast-tracking of colonoscopies. Perceived barriers for patient participation in the NBCSP include high GP workload and GPs feeling they have been precluded from the NBCSP, making it challenging for them to promote bowel cancer screening to their patients.

Research shows that GP endorsement is a key predictor for bowel cancer screening.16,17 An Australian survey18 found more than 90% of respondents would be ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to have an FOBT every two years if recommended by a doctor, while invitees of the NBCSP pilot who did not participate reported a greater likelihood of doing so if recommended by a GP.19 Our study found that a number of GPs were proactive in promoting bowel cancer screening to their patients. Conversely, time pressures and excessive workloads prevented some GPs from discussing bowel cancer screening with their patients. This result is not surprising, given 40% of Australian GPs have reported experiencing excessive workloads, which was found to be more prevalent in rural areas.20 Koo et al21 reported lack of time as the main barrier for GPs not recommending bowel cancer screening to their patients. This was especially true for GPs working in rural Australia.22 Given the current workforce shortage for GPs in rural and remote Tasmania,11 it is clear that strategies to support GPs to promote bowel cancer screening need to take workload issues into account.

The NBCSP has recognised that preclusion of GPs from the design and implementation of the program is also a key barrier to gaining GP endorsement.23 They reported that GPs ‘do not feel part of the program and feel that their expertise with patients and their role in influencing health behaviours has not been considered in the program design’.24 This view was echoed by GPs Frank and Stocks, who stated that ‘general practice must be made more central in the NBCSP for it to succeed’.24 GPs in our study expressed similar sentiments. Most notably, the direct mailout of kits to eligible participants meant GPs were unaware when their patients received a screening kit in the mail, making it difficult for them to support the NBCSP in a timely manner.

Despite various barriers, GPs identified several strategies that would likely facilitate patient participation in the NBCSP. They included practical ideas that could be implemented within a practice with minimal effort and resources, such as:

- prominent in-room posters

- showing patients what the kit looks like and how to use it

- encouraging patients to take the test

- using existing patient management software to remind GPs which patients received a kit in any given year.

Additional strategies would rely on the NBCSP, communities, other health professionals and the Australian Government to support GP efforts, including:

- distributing kits through general practice rather than direct mail-out

- providing GPs with demonstration kits

- conducting community education sessions

- promoting the NBCSP through pharmacies and community health nurses

- training more rural GPs to complete colonoscopies.

This last point is especially relevant given the long waiting times for diagnostic assessment seen in regional and remote areas.25 These waiting times could be reduced if GPs were able to conduct colonoscopies within their local communities.

Although the GPs in this study identified numerous barriers and enablers to bowel cancer screening, it is unknown whether their views were based on personal experience, opinion or evidence. Their suggestions for improving uptake of the NBCSP should therefore be seen as opportunities rather than unequivocal solutions. It is also important to recognise the tension between strategies that require greater resourcing (eg distribution of kits via general practice) and high GP workloads. By improving the latter, through government policy initiatives and improved funding arrangements, GPs will be in a better position to support the NBCSP and increase participation in bowel cancer screening in rural Tasmania.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that it was conducted in only four LGAs in Tasmania with a relatively small non-random sample of doctors. The findings may resonate with others, though cannot be generalised to other rural GPs and communities across Australia.

This article also focused solely on GP perspectives and did not report on the views of community members and other health professionals. While this is a limitation, we felt it was important to feature the GPs’ views and aimed to ensure their voices were well represented on the issue of bowel cancer screening in rural communities.

Conclusion

GPs are important for improving participation in the NBCSP. Incorporating GPs’ views on barriers and enablers for screening is key to improving NBCSP participation in rural Tasmania and Australia more broadly.

Appendix 1 – Sociodemographic community profile of participating Local Government Areas compared to whole-of-state population