Medication use is ubiquitous in older Australians living in aged care and plays a significant part in the quality of care of consumers.1 While medications can be beneficial in treating many conditions, they can also cause harm.

Older Australians are particularly vulnerable to medication-related harm due to multiple chronic conditions requiring multiple medications (polypharmacy) and the physiological changes of ageing.2–4 Research has shown that 98% of aged care residents have at least one medication-related problem, and over 50% are prescribed at least one potentially inappropriate medication (ie risk outweighs the benefit).5

The impact of medication-related harm on the Australian healthcare system is significant. Each year, 400,000 people present to emergency departments and 250,000 people are admitted to hospital because of medication-related harm.5 This comes at a cost to the healthcare system of more than $1.4 billion.5 In particular, medication-related harm is common in aged care residents and is responsible for up to 30% of unplanned hospital admissions.6

In addition, there is a significant impact on mortality, morbidity and quality of life for those experiencing medication-related harm.2 Medication-related harm has been associated with both functional and cognitive decline in the older population,2 therefore affecting the ageing experience.

In 1997, the Government introduced Residential Medication Management Reviews (RMMRs) for implementation by general practitioners (GPs) and accredited clinical pharmacists (ACPs). This program was part of a suite of interventions to promote a collaborative and educational approach to mitigating medication-related harm in aged care. In this article, the authors discuss this program in the context of its benefits and limitations and how an enhanced program, introduced in April 2020, can ensure that medications are used in a safe and judicious manner that optimises health for residents over their life course.7 This article will focus on how the new program will support GPs with respect to medication management in the aged care population.

RMMR program (1997–2020)

For the past 20 years, the RMMR program has funded one collaborative medication review per year for aged care residents, initiated by the GP every 12 months or more frequently if there is a pressing clinical need. RMMRs could be conducted by an ACP after referral from a GP.8 Small studies have shown the program to be effective in identifying medication-related problems and engaging GPs to act on ACPs’ recommendations.2,9,10 However, this evidence is limited, especially with respect to resident outcomes.11,12

Limitations of the program and barriers to medication changes discussed in the literature include the following:

- Some GPs do not feel supported to make medication changes. This may be due to multiple prescribers being involved in the resident’s care and/or fear of poor outcomes after changing medications.13

- Infrequent medication reviews cannot address all the needs of this population.6 Residents are clinically complex individuals, many with cognitive deficits, which makes changing medications challenging.13

- There is no pathway or remuneration for ACPs to support GPs to make changes over time or to follow-up their recommendations to evaluate resident outcomes.8,14

- Demonstrating meaningful outcomes of the program has been hampered by the restrictive program rules and disparate record keeping.14

In late 2019 and early 2020, evidence of ongoing medication-related harm in aged care was published in two key documents. The Royal Commission’s Interim Report, Neglect, drew on professional and consumer feedback as well as research findings.15 The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s report, Medication safety: Aged care, reviewed medication studies in Australian aged care.6

Key issues identified in these documents included:

- an unacceptably high prevalence of use of medications associated with chemical restraint

- inappropriate dosing of medications in older residents with compromised renal function

- use of medications that worsen cognitive decline in residents with dementia

- long-term use of medications without ongoing clinical need.

In addition, the Australian Medical Association’s submission to the Royal Commission in 2019 highlighted two concerns with respect to medication management in aged care:16

- limited access to RMMRs by GPs due to program rules that do not adequately address the clinical complexity of residents

- overuse of chemical restraint in aged care.

Enhanced RMMR program (April 2020–)

Consideration was given to the aforementioned evidence, and in April 2020, the Government announced the following changes to the RMMR program:

- Broadening the referral base – in addition to GPs, non-GP specialists can now refer for the initial RMMR.

- Ongoing cycle of care for at-risk residents – two follow-up reviews are permitted at the discretion of the clinical pharmacist.

- Timeliness of care – the cycle of care must be completed within nine months of the initial review.

- Collaborative medication management – this is supported by regular reporting and discussions within the healthcare team including families/carers and residents where possible.

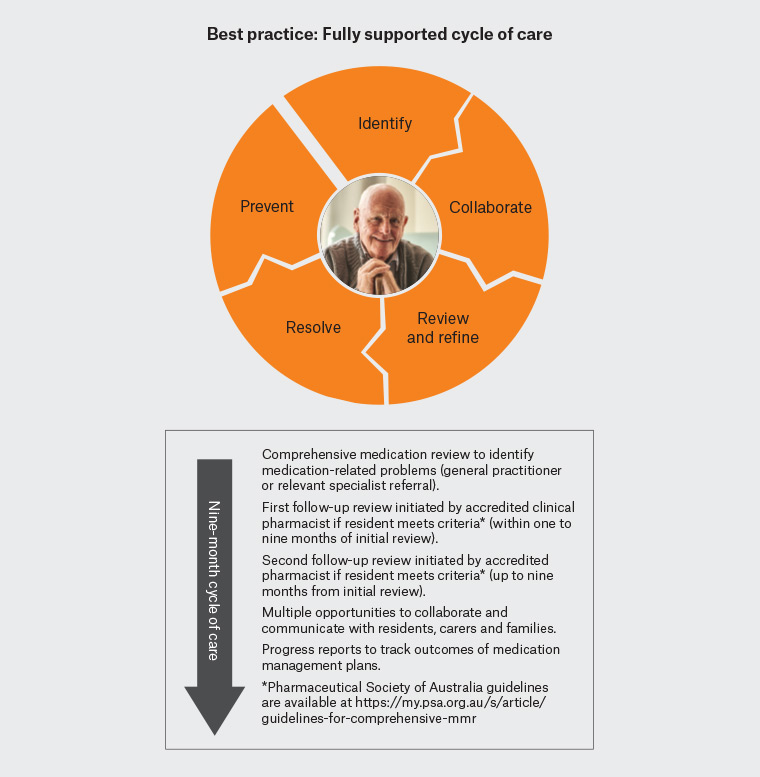

This new enhanced program has now been integrated into the 7th Community Pharmacy Agreement, which was ratified in June 2020.7 These enhancements are intended to provide a complete cycle of care, allowing ongoing collaboration between accredited ACPs, GPs and other prescribers over nine months. This will facilitate the development of a comprehensive medication management plan in consultation with the resident/family and facility staff (Figure 1). This plan can be integrated into the broader care plan and life goals of each resident.

Figure 1. Supporting general practitioners with progress reports to track outcomes of medication management plans

Importantly, clinical responsibility of outcomes will be shared across the professional groups. Collaborative follow-ups will allow a healthcare team approach to medication changes and monitoring resident response over time. Progress reports will provide a history of outcomes with respect to successful and unsuccessful medication changes. The program is intended to provide more opportunity for residents, carers and families to be involved in the decision-making process.

In situations in which a non-GP specialist is the referrer, the RMMR report must be sent to both the relevant specialist and treating GP and uploaded to My Health Record if the resident has one.17 Where appropriate, the reviewing ACP can facilitate discussions between the relevant specialist and GP.

Best-practice medication review process

The following case study demonstrates how the new program provides ongoing ACP support to GPs and aged care staff to monitor changes to high-risk medications.

Case

A female aged 80 years who was a newly admitted resident of an aged care home was frequently aggressive and wandering off-site, which required extensive monitoring by aged care staff and treatment with an antipsychotic and a benzodiazepine. She was referred for an RMMR as these medications are known to be high risk in the older population.

Medication-related problem

The resident was prescribed regular risperidone 1 g twice daily (and 1 g as needed [PRN]) and oxazepam 15 mg in the morning for managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). The ACP noted that the resident’s problematic behaviours had lessened with use of these medications; however, the resident was complaining of sedation.

ACP recommendations to GP (initial RMMR report and case conferencing)

Considering the stabilisation of BPSD and sedation, a trial reduction of the risperidone is warranted. Ongoing monitoring of behaviours using a behaviour management plan including non-pharmacological interventions is recommended. This has been discussed and agreed with the resident and care manager. I also recommended the Dementia Training Australia (DTA) Program to educate the staff with respect to non-pharmacological management of BPSD.

Outcomes

Medication will be weaned per regimen discussed over the phone, and I noted you have uploaded my report to My Health Record.

First follow-up review (six weeks later)

The ACP noted that risperidone had been slowly weaned to 0.5 mg at night (1 g PRN dose remained), with monitoring for adverse outcomes/emergence of symptoms using a behaviour chart. All other regular and PRN medications remained the same, and medical history was stable. Behaviours remained stable, and the resident was less sedated. The staff had accessed the DTA training materials and were undertaking a training needs assessment for all staff.

ACP communication to GP (second report to GP)

Given the resident’s behaviours are stable, reduction in the PRN dose of risperidone is now warranted together with a trial reduction in oxazepam over time. This will be followed up in three months.

Second follow-up review (three months later)

The ACP noted risperidone had been weaned to 0.5 mg twice daily PRN (two doses in the past week were given) and the nightly dose ceased, and the morning oxazepam had been down titrated and ceased. The resident’s behaviours were being monitored and had been stable over the past three months.

ACP communication to GP (third report to GP)

Thank you for the ongoing management of this resident’s medications. The resident is stable and is responding well to non-pharmacological interventions such as distraction therapy. It is reported by staff that she is more willing to participate in activities. Please review the need for ongoing PRN risperidone, with a view to ceasing if the resident remains stable and no doses are given in the next three months.

Claiming for GP services in the new RMMR program

Claiming for the initial review remains the same as previous arrangements. Claiming for follow-up reviews has not been allocated a specific Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item number; however, Table 1 includes suggestions on how GPs may incorporate follow-up reviews into an established funded consultation (GP initiated). Multidisciplinary care plans, comprehensive medical assessments and case conferences are useful items for coordinating care with the healthcare team, including non-GP specialists. However, ACPs do not have access to MBS item numbers and will not be remunerated for participation. In instances where a GP cares for several residents at an aged care home and there are multiple reviews to be discussed, several case conferences could be undertaken in one sitting.

| Table 1. Medicare Benefits Schedule claiming options for complete cycle of care |

| RMMR-related general practice service |

Medicare Benefits Schedule item number claiming options |

| Initial RMMR |

903 |

| First follow-up |

Multidisciplinary care plan (731), case conferences (735, 739, or 743), standard/after-hours consultation or comprehensive medical assessments (701–707) |

| Second follow-up |

Multidisciplinary care plan (731), case conferences (735, 739 or 743), standard/after-hours consultation or comprehensive medical assessments (701, 703, 705 or 707) |

| RMMR, Residential Medication Management Review |

Evidence of program effectiveness

Comprehensive program evaluation will now be possible as the enhancements allow tracking of activities over time including types of medication-related problems identified, ACP recommendations, GP responses to recommendations and resident outcomes.

Robust, independent studies are necessary to ensure that the program meets its objectives and the needs of the aged care residents. At a minimum, studies showing the impact of the enhanced program should address key recommendations of the Royal Commission with respect to chemical restraint and the pilot medication quality indicators in aged care: use of antipsychotics and polypharmacy.15,18