The COVID-19 pandemic has grown exponentially worldwide since December 2019.1 Brazil implemented social distancing on 13 March 2020,2 which caused increasing distress and directly affected individuals’ mental health,3 work structures, lifestyles and interpersonal relationships.2

The lifestyle medicine pillars are based on healthy eating, routine exercise, stress management, avoidance of risky substances, positive relationships and better sleep.4 People who adopt healthy lifestyle pillars have a longer life expectancy, free from major chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer, when compared with people who do not adopt healthy lifestyle pillars.5–8 Spirituality helps individuals to develop a sense of purpose in life and has been shown to equip individuals with highly effective strategies for coping with stress.9 Considering the pandemic’s impact on health behaviours, people will likely change how they deal with each pillar.

The aim of this study was to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic changed medical students’ six lifestyle pillars and to investigate the effect that their previous lifestyles had on their emotional wellbeing during the social distancing period.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included medical students representing all six undergraduate years of a Brazilian private medical school. The data were collected through a digital questionnaire. Students who agreed to respond anonymously and signed the digital consent form were included. The local centre’s ethics committee approved the study protocol (CAAE: 34503620.6.0000.5239).

Demographic data included sex (male/female), age (years), undergraduate year (from first to sixth year), marital relationship (yes or no) and living condition (alone or not). Information about the lifestyle medicine pillars, before and during the pandemic, included: quality of sleep, duration (minutes) and intensity of weekly physical exercise, quality of eating, spirituality, tobacco and alcohol use and interpersonal relationship quality. In addition to the lifestyle pillars, participants were also asked about their emotional wellbeing during the social distancing period.

In terms of physical exercise, participants were classified as ‘inactive’ if they were sedentary, or ‘sufficiently active’ if they performed light or moderate exercise that lasted at least 150 minutes per week or vigorous exercise that lasted 75 minutes per week. If participants were active but did not meet the requirements for sufficient activity, they were considered ‘insufficiently active’.

The research questionnaire included questions about quality of emotional wellbeing and lifestyle pillars on a five-point Likert scale of very good (5), good (4), fair (3), poor (2) and very poor (1). Sleep quality, eating quality, stress management (represented by spirituality) and interpersonal relationship pillars were reclassified as present if self-reported as good/very good and absent if self-reported as fair/poor/very poor. The exercise pillar was classified as present if any amount of physical exercise was reported and absent if the participant was sedentary. The pillar pertaining to avoidance of risky substances was classified as present or absent according to tobacco use (yes or no), as any tobacco use was considered toxic. Alcohol consumption was not included in this pillar because alcohol consumption was not quantified; therefore, the researchers could not classify it as abusive or non-abusive.

The total number of lifestyle pillars classified as present before the pandemic was counted for each student. Among medical students who previously consumed tobacco or alcohol, the researchers identified those who reduced, maintained or increased use during the pandemic. The statuses for each of the other five pillars were also compared to classify students who worsened, maintained or improved their lifestyles.

Emotional wellbeing was assessed using the Likert scale and classified as present if good/very good and absent if fair/poor/very poor during the pandemic.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, USA) and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)/IBM for Windows (version 25.0). Numeric data are presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical data are presented as number (percentage). We used Mann–Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests to compare variables with non-parametric distribution. Chi-square/Fisher tests were used to compare frequencies. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 1059 medical students, 548 answered the questionnaire and were included in the analysis. No difference in sex distribution or age existed between responders and non-responders. The studied population’s demographic and lifestyle characteristics before the pandemic appear in Table 1.

| Table 1. Pre-pandemic demographic and lifestyle characteristics of medical students (n = 548) |

| Demographic characteristics |

n (%) |

| Sex |

|

| Female |

412 (75.2) |

| Male |

136 (24.8) |

| Age (years)* |

21.5 (20–23.8) |

| Undergraduate year |

| First year |

88 (16.1) |

| Second year |

100 (18.2) |

| Third year |

87 (15.9) |

| Fourth year |

91 (16.6) |

| Fifth year |

90 (16.4) |

| Sixth year |

92 (16.8) |

| In a marital relationship |

285 (52.0) |

| Living alone |

22 (4.0) |

| Lifestyle characteristics |

| Physical exercise status |

| Inactive |

112 (20.4) |

| Insufficiently active |

222 (40.5) |

| Sufficiently active |

214 (39.1) |

| Quality of sleep |

| Very good/good |

216 (39.4) |

| Fair/poor/very poor |

332 (60.6) |

| Quality of eating |

| Very good/good |

304 (55.4) |

| Fair/poor/very poor |

244 (44.5) |

| Quality of interpersonal relationships |

| Very good/good |

477 (87.0) |

| Fair/poor/very poor |

71 (13.0) |

| Spirituality |

| Very good/good |

249 (45.5) |

| Fair/poor/very poor |

299 (54.5) |

| Alcohol consumption |

430 (78.5) |

| Current tobacco use |

71 (13.0) |

| *Data presented as median (interquartile range) |

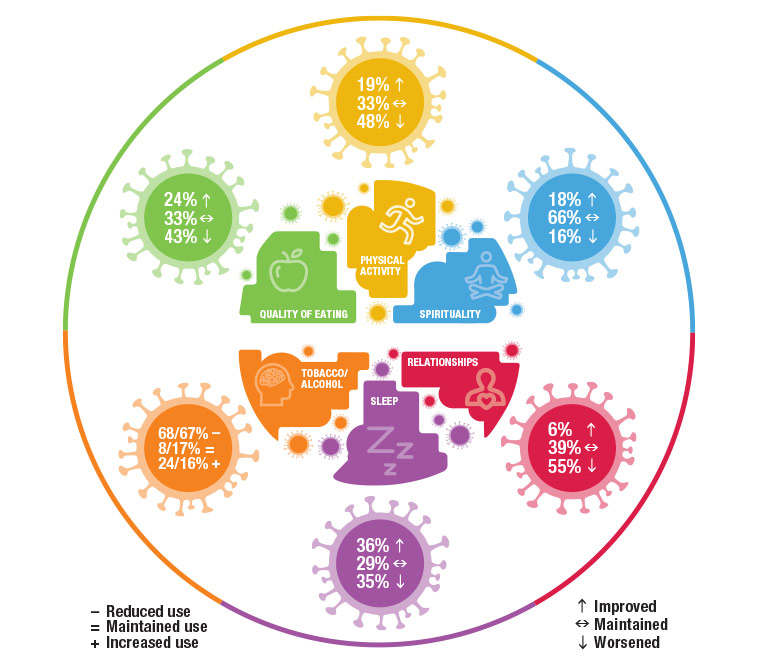

Figure 1 shows the pandemic-related changes in statuses for the six lifestyle pillars. Among the students whose physical exercise pillar was positively affected by the pandemic, 97 (91.5%) were female and 9 (8.5%) were male. Those negatively affected included 114 (63%) female and 67 (37%) male students (P <0.01). Those whose physical activity improved were younger than those whose physical activity worsened (median: 21 [interquartile range (IQR): 19–23] years of age, compared with 22 [20–24]; P = 0.017). No differences in sex distribution or age appeared among those with changes to the quality of their eating habits, sleep, interpersonal relationships and spirituality. Students who started or increased smoking during the pandemic were older than those who decreased smoking (24 [22.5–24] years of age, compared with 22 [21–23]; P = 0.013).

Figure 1. Changes in the six lifestyle pillars of 548 Brazilian medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adapted with permission from American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine (www.lifestylemedicine.org/ACLM/Tools_and_Resources/Print_Resources.aspx)

During the pandemic, 395 (72.1%) students reported an absence of emotional wellbeing. Those who reported the presence of emotional wellbeing (27.9%) during the pandemic fulfilled more pre-pandemic lifestyle pillars when compared with those who felt an absence (4 [3–4], compared with 3 [2–4]; P = 0.006]). No associations were seen between the presence of emotional wellbeing during the pandemic and sex, age, living alone or being in a marital relationship.

Discussion

In this study, the researchers investigated the influence of the number of lifestyle pillars that Brazilian medical students adopted on their emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. They also observed the pandemic’s impact on students’ lifestyle habits, both positive and negative.

Large European and North American prospective studies have shown that constant healthy behaviours enhance quality of life and longevity.5–8,10 Strategies to improve these habits during the COVID-19 pandemic were well addressed by Smirmaul et al11 and O´Keefe et al.12 In the present study, the number of lifestyle pillars that medical students had adopted prior to the pandemic was higher in those reporting better emotional wellbeing during the pandemic, which may indicate that these lifestyle pillars allowed the students to better cope with this stressful situation.

Sleep is an essential biological function that mediates and reflects psychosocial functioning and quality of life.13 Its chronic restriction and poor quality influences wellbeing and mental health.14 In the present study, 60% of the students already had regular- or poor-quality sleep before the pandemic, similar to the Ribeiro et al study.15 This similarity can be explained by the heavy academic schedule of medical students.16

As expected, 34.5% of the students reported that their sleep quality worsened during the pandemic, similar to results seen in a Greek study.17 In contrast, approximately 36% of students in the present study reported improved sleep quality during the social distancing period, possibly because their time to rest increased as a result of reduced external activities.

Physical activity reduces depression and anxiety,18 stabilises mood and improves cognition.19,20 In Brazil, 47% of the population is insufficiently active.21 However, almost 80% of the students in this study were previously physically active, but only 39.1% met the criteria for sufficient activity.22

Home isolation has previously been shown to profoundly decrease moderate-to-intense physical activity levels and increase sedentary behaviour.23,24 In the present study, 33% of students worsened in the physical exercise pillar. Among those who improved, most were female and younger. Diverging from the present sample, men in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, had approximately 38% more opportunities to exercise during the quarantine period than women.25 However, a study of Italian university students concluded that females (approximately 22 years of age) who were previously active were more likely to reach the recommended levels of physical activity during the pandemic.26

Although 55% of students in this study self-reported a previously good or very good quality of eating, 43% of students’ eating habits worsened. This could be due to the difficulty of going to markets, resulting in changes in an individual’s eating patterns toward consuming less fresh food and more ultra-processed foods.20,27

Tobacco and alcohol use among students was 13% and 78%, respectively, before the pandemic. Factors associated with tobacco and alcohol use among medical students are peer pressure, favourable social activities, external factors, work overload and proximity to medical residency exams.28 During the pandemic, there was a decrease in tobacco and alcohol use in 68% and 67% of medical students, respectively. The absence of triggering factors that occurred as a result of pandemic-imposed distancing, such as the cessation of on-site school activities and social gatherings, may explain this result.

The pandemic increased individuals’ vulnerability to negative feelings, such as anxiety and fear. Thus, spirituality could be important for dealing with the new reality.29 However, the present results indicate that only 18% of students improved this pillar during the pandemic. Unlike the present study, Lucchetti et al found that most students experienced spiritual growth during the pandemic, and three out of four students declared that spirituality helped them to cope with the effects of social distancing.29

Social support is essential for maintaining quality of life.30 In the present study, however, psychological wellbeing during the pandemic was not associated with living alone nor marital status.

Social distancing affected interpersonal relationships and caused loneliness.31,32 Although 87% of the medical students reported a good or very good relationship status before the pandemic, 55% admitted this domain worsened during social distancing.

This study has limitations. A self-reported questionnaire was used, which could have led to different interpretations of the significance of each lifestyle pillar, and of emotional wellbeing. Alcohol use could not be included in the risky substance pillar because consumption was not quantified to identify abusive use. Despite having a good sample response rate, the study also only included students from a single Brazilian private medical school.

In conclusion, the results reinforce the importance of adhering to as many lifestyle pillars as possible to preserve emotional wellbeing during periods of stress such as the COVID-19 pandemic.