This article is the fourth in a series of articles on important topics in neurology.

Parkinson’s disease is now understood to be a multisystem disorder.1 Awareness of the need to assess and actively manage non-motor symptoms to improve quality of life for people living with Parkinson’s disease is increasing.2 However, awareness of the impact of neurological damage on the person’s ability to communicate and swallow effectively is limited. The precise neural mechanisms of dysarthria (difficulties with speech and voice) and dysphagia (swallowing difficulties) have not been identified to date.3 Language processing deficits specific to Parkinson’s disease have been described, although the relationship with broader cognitive deficits is unclear.4,5 Early identification of risk is important in treating dysphagia to help prevent pneumonia in people with Parkinson’s disease.6

Communication difficulties

For almost 90% of those living with Parkinson’s disease, communication difficulties have a significant impact on day-to-day functioning.

4 Early onset of speech difficulties is common, and these become increasingly debilitating as the disease progresses.

7,8 Emerging research has identified variations in voice frequency in prodromal Parkinson’s disease up to five years before diagnosis.

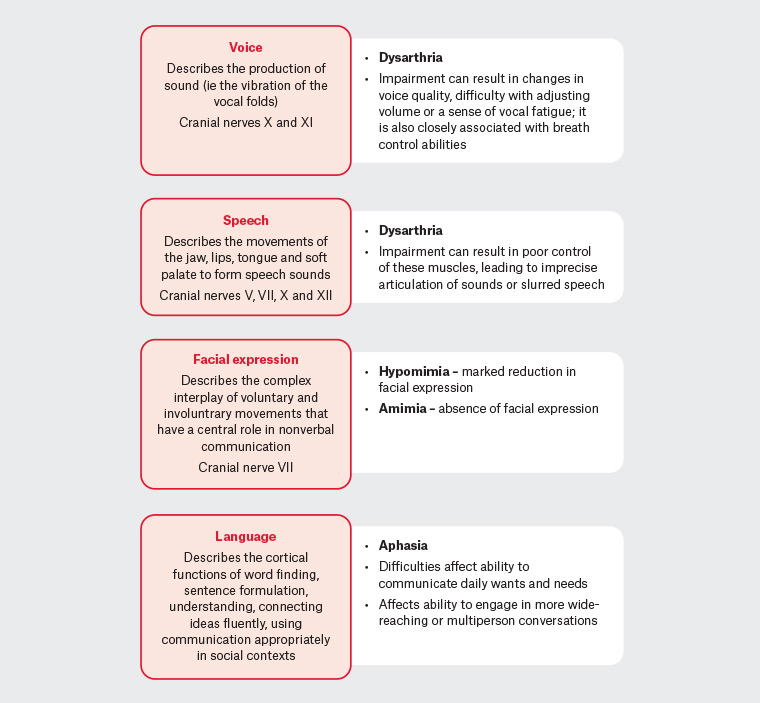

9 Figure 1 briefly describes communication-related terminology relevant to this discussion.

Figure 1. Communication-related terminology

Hypokinetic dysarthria is the specific dysarthria experienced by people with Parkinson’s disease.10 This speech disorder is characterised by low volume, monotone speech with poor articulation and slurred sounds. Other changes associated with hypokinetic dysarthria include breathiness and irregular pauses with rapid speech rate.8 Notable is the misperception by the person with Parkinson’s disease when speaking softly that their speaking is normal in volume. When asked to speak more loudly, the person may be able to do so for a short period;11,12 however, maintaining a louder volume takes considerable effort and increases the frustration experienced when trying to communicate. Caregivers, family and friends may have limited awareness of the energy required to speak more loudly.8

People with Parkinson’s disease frequently report word-finding difficulties; however, caregivers most commonly identify comprehension difficulties as having a greater impact on everyday communication than word-finding difficulties do. While language difficulties increase with cognitive decline, 30–40% of people with Parkinson’s disease without significant cognitive deficits have unique linguistic difficulties, such as difficulties with comprehension, word finding and verbal fluency.5,13

A further contributor to communication difficulties is the marked reduction in facial expression (hypomimia) or amimia (absence of facial expression). As an early symptom of Parkinson’s disease, this is often misinterpreted as aloofness, lack of interest or indicative of depression. This also increases social isolation.6 Recent research suggests that amimia is a ‘potential predictor of global Parkinson’s disease severity, including axial symptoms and cognitive decline’.14

All these factors, in conjunction with cognitive challenges such as distractibility, difficulty formulating ideas and reduced attention span, adversely affect the person’s ability to engage in social interactions. These communication difficulties markedly affect the quality of life of the person living with Parkinson’s disease and that of their caregiver.5,15

Swallowing difficulties

Over 80% of patients with Parkinson’s disease will develop dysphagia involving the different phases of swallowing: oral preparatory and transportation, pharyngeal or oesophageal (Table 1).16,17 While dysphagia is frequent, it is underdiagnosed because of initial compensatory behaviours, poor self-awareness and limited use of screening tools.17 Compensatory behaviours include reducing bolus size, changing food consistency and excluding foods that cause difficulty when eating.12 Although both mild and severe oesophageal dysfunction has been widely reported in Parkinson’s disease, a clear association with oropharyngeal dysphagia has not been identified.18 However, oesophageal dysfunction is outside the scope of this discussion.

| Table 1. Prevalence of dysphagia |

| Study |

Type |

Findings |

| Kalf et al37 |

Meta-analysis |

- Subjective dysphagia in one-third of community-dwelling patients

- Objectively measurements indicated that 80% of patients with Parkinson’s disease were affected

|

| Pflug et al38 |

Prospective cohort study (n = 119) |

- Common at all stages of disease

- Only 5% had unremarkable deglutition

- Aspiration in 20% with disease duration <2 years

- Of the participants, 73% denied difficulty swallowing or problems with choking (16% of these had critical aspiration)

|

| López-Liria et al6 |

Systematic review |

- In the early stages of Parkinson’s disease, 80% of patients had dysphagia

- This rose to 95% dysphagia in the advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease

|

Oropharyngeal dysphagia affects the person’s quality of life and socialisation and has been shown to contribute to malnutrition and dehydration,19 with poor nutritional status adversely affecting the person’s capacity to undertake activities of daily living.20 The person’s ability to take oral medication safely is also impaired,16 with tablets remaining in the oral cavity or lodging in the pharynx.21 Oropharyngeal dysphagia markedly increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia, identified as the leading cause of death in Parkinson’s disease.22

Sialorrhea (drooling) is often associated with dysphagia. Drooling has been reported in 37% of people with Parkinson’s disease, with the highest rates in those over 80 years of age.23 Hypomimia, resulting in ‘reduced lip seal’, may also contribute to drooling. This symptom increases the risk of dry mouth and dehydration, increases speech difficulties and contributes to social isolation because of embarrassment.23

Early identification of dysphagia is advised to enable management of the serious negative consequences of oropharyngeal dysphagia and decrease mortality.17 A multinational consensus on dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease recommends seeking signs and symptoms at diagnosis, with re-evaluation preferably every year (Table 2).24 Severe dysphagia in late-stage Parkinson’s disease predicts a rapidly worsening outcome and requires active management.25

| Table 2. Screening for dysphagia: When should dysphagia be suspected in people with Parkinson’s disease?24 |

| Evidence of one or more of these |

- Increased eating time (meal duration)

- Post-swallowing coughing

- Post-swallowing gurgling voice

- Drooling

- Choking

- Breathing disturbance

- Unintentional weight loss

- Difficulty swallowing medication

- Sensations of food retention

- One or more episodes of pneumonia

|

| Yes, to one or both questions |

- Have you experienced any difficulty in swallowing food or drink?

- Have you ever felt as if you are choking on your food?

|

| Initial screening |

| Self-report questionnaire |

Swallowing disturbance questionnaire (Appendix 1)39 |

| Thorough medical history |

|

| Recommend |

Obtain collaborative history from care giver/partner as compensatory behaviours may reduce awareness of swallowing difficulties12 |

Impact of communication and swallowing difficulties on quality of life

For the person living with Parkinson’s disease, impaired communication and dysphagia contribute to widely reported decreased self-confidence, increased self-consciousness and social anxiety.4,26 Lack of understanding of the person’s condition results in reports that ‘people talk over them, talked for them, did not wait for an answer, ignored them, assumed they were stupid’.4 Self-stigma, where the person with Parkinson’s feels embarrassed and fears the reactions of other people, also contributes to withdrawal, increasing social isolation and depression.27 Difficulties in engaging in meaningful communication with family, friends and work colleagues combined with the impact of dysphagia, drooling and fear of choking leads to a reluctance to engage in social interactions.24 Caregivers experience increasing difficulties as they take on more communication-related activities for the person with Parkinson’s disease while also struggling to communicate effectively.28

Interventions for communication and swallowing difficulties

Early referral for speech pathology is recommended even if there are no overt communication symptoms. To date, pharmacological and surgical interventions have not demonstrated consistent beneficial outcomes for communication difficulties. A growing evidence base demonstrates improvements in speech production and beneficial effects in reducing symptoms of hypokinetic dysarthria with speech pathologist–delivered behavioural approaches (Table 3).8,29,30 Programs such as the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT) LOUD or SPEAK OUT are available from trained speech pathologists in Australia. Speech pathologists are also trained in assisting with aphasia and cognitive-related communication difficulties. Emerging findings also suggest that participation in therapeutic group singing for people with Parkinson’s disease affects social interaction positively and may improve vocal function and respiratory pressure.31,32

| Table 3. Evidence for speech pathology interventions |

| Study |

Type |

Findings |

| Levy et al40 |

RCT |

Intensive speech treatment targeting voice improves speech intelligibility. |

| López-Liria et al6 |

Systematic review |

Expiratory Muscle Strength Training shown to be successful in improving swallowing and oropharyngeal function and reducing the risk of choking and/or aspiration.Other interventions, including swallow manoeuvring, postural treatment and compensation strategies, require well-designed RCTs with larger populations. |

| Muñoz-Vigueras et al29 |

Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs |

Speech language therapy for reducing hypokinetic dysarthria improves perceptual intelligibility, sound pressure level and semitone standard deviation. |

| Miles30 |

Pilot |

LSVT LOUD demonstrates additional spread effects on pharyngoesophageal deglutitive function and involuntary cough effectiveness. |

| LSVT, Lee Silverman Voice Treatment; RCT, randomised controlled trial |

Early referral to a speech pathologist for those with a positive swallowing screening test is likewise important to identify and reduce the risks of aspiration, choking, dysphagia-related malnutrition and dehydration. Following clinical assessment, the speech pathologist may request a referral for further assessment to determine the safest textures/consistencies for oral intake. Video fluoroscopic swallowing studies and fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing are recommended as first-line diagnostic tools if available.3,24 These may be accessible via major urban hospitals with speech pathology outpatient services.

Access to specialist speech pathologist services is variable,33 especially for those living in remote and rural regions in Australia. Speech Pathology Australia – Find a Speech Pathologist (www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au) can be used to identify the closest public and private services. Advances in technology-enabled care increasingly support home-based multidisciplinary care.34 Telerehabilitation offers the possibility of communication and swallowing assessment and interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease35 and is endorsed by Speech Pathology Australia.

Referral to a dietitian is also recommended to help ensure adequate nutrition for those with swallowing difficulties.36 Major hospitals and community health centres may offer the required services; alternatively, Dietitians Australia – Find a dietitian (https://member.dietitiansaustralia.org.au/faapd) can be used to find the closest dietitian services.

Vignette as told by Trevor and Pat

Trevor (age 70 years) and Pat (age 69 years) enjoyed three years of retirement travelling around Australia, camping and bushwalking. Trevor then noticed a change in his gait, and his sense of smell and taste began to disappear. Eating deteriorated; he recalls:

I would only be halfway through my meal and everyone is finished and waiting … My speech was bad, my voice was soft, and I mumbled a lot.

Initially diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms continued to deteriorate. A second opinion identified Parkinsonism and normal pressure hydrocephalus. Insertion of a shunt dramatically relieved symptoms for six months, and Parkinson’s disease was almost excluded. Symptoms again worsened, and diagnosis remains Parkinson’s disease with normal pressure hydrocephalus, though this is challenging because of ongoing fluctuations in symptoms, decline in condition and lack of response to levodopa.

I talk a lot softer and lose my breath while I am talking. If I don’t concentrate on taking a breath while I am talking, it just fades into nothing … especially if I get excited about something.

When Trevor is with his friends with Parkinson’s disease:

It’s hard when someone goes wrwrwrwrwr … you can’t understand them … it’s so hard … we are the ones doing it and we think we are not. I think I’m speaking clearly and loudly … until it is played back.

For Trevor, taking tablets is ‘the worst thing’:

I don’t cough or choke, I have to get the tablet placed correctly in my mouth, on my tongue for the initial swallowing action. If you don’t concentrate on where it is in your mouth, you can’t swallow it.

Trevor drools at times, while at night, his mouth is dry. Sucking a lolly helps. Eating is challenging:

I eat mince and things that are softer and more palatable.

When you go out … you worry … people are watching you, I lean over … because I could drop food or can’t chew it and have to spit it out … it’s demoralising when you’ve got to do things like that.

The speech pathologist assessed swallowing and talking and gave Trevor speech exercises:

The more I say them the better I get … when I don’t do them for a while ... by midday I’m just not understandable … my poor short-term memory doesn’t help though, sometimes when I talk, I forget what I’m talking about, so I only get halfway through what I’m saying.

Trevor also uses an app designed for Parkinson’s speech.

Over the past year, Trevor’s mobility has deteriorated, resulting in multiple fractures and admissions to hospital. He falls at least once a day. Both Trevor and Pat now require hearing aids. Pat says:

Day to day, the biggest problem we have is his voice … I constantly struggle to either hear him or understand him … I can hear him at other places talking to other people and it’s fine ... he just seems to think he doesn’t have to try as hard, this is just Pat, um so yeah, a bit of frustration, not so much friction. His falls worry me but it’s something that you can probably get on top of, I hope.

Conclusion

Speech, language and swallowing difficulties are everyday occurrences at all stages of Parkinson’s disease. As a result of the complex neural mechanisms involved, medications that help with motor symptoms are not often effective for these difficulties. Early identification and referral for behavioural interventions by a speech pathologist and dietitian support for swallowing difficulties have been shown to be effective in helping those who live with Parkinson’s disease, improving their quality of life and reducing the risk of premature death due to aspiration. The general practitioner plays a key part in identifying these difficulties and initiating a multidisciplinary team approach to care.

Key points

- Communication and swallowing difficulties adversely affect the quality of life and social engagement of and increase morbidity in people with Parkinson’s disease.

- Limited self-awareness of swallowing and communication difficulties can delay early intervention.

- Early referral to a speech pathologist with specialist skills in assessment and therapeutic interventions for Parkinson’s disease is recommended.

- Active engagement in speech pathologist–led Parkinson’s disease–focused therapeutic interventions has been demonstrated to improve both communication and swallowing problems.

- Referral to a dietitian to assist in ensuring adequate nutrition for the person with swallowing difficulties is required.