Background

Health literacy is a social determinant of health, with lower levels linked to suboptimal health outcomes. There is a gap in the literature regarding the value of health literacy assessment among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and best methods with which to perform such assessments in general practice.

Objective

Literature was reviewed to determine what is known regarding health literacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the availability of assessment tools and the implications for general practice.

Discussion

Despite its effect on health outcomes, the health literacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is poorly understood, with no validated assessment tools specifically tailored to this population. Culturally insensitive screening of health literacy has potentiality to disaffect; thus, practitioners should consider assessments aligned with Indigenous methodologies such as conversational or yarning approaches or the use of a small number of screening questions. Practitioners are encouraged to adopt a universal precautions approach and use culturally appropriate conversational styles to optimise communication and healthcare outcomes.

Health literacy extends beyond the societal understanding of literacy. It refers to one’s ability to understand, question and make informed decisions about their health.1 The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) recognises that low health literacy can result in poorer health outcomes and lower utilisation of health services such as screening and preventive care.2 If health literacy is low, awareness of this allows the practitioner to tailor their communication style accordingly to optimise the patient’s understanding, decision making and health outcomes.3 Higher levels of health literacy can improve self-reported health status, increase health knowledge and reduce hospitalisations and healthcare costs,4 while lower levels can affect an individual’s health-related behaviours, health service utilisation and ability to navigate health systems. As a potentially modifiable aspect of a person’s health, a better understanding of patient and community health literacy levels can assist in optimising healthcare provision. In 2018, the Australian Bureau of Statistics used the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) to assess Australians’ health literacy. The survey revealed that 33% of Australians always found it easy to discuss health concerns and actively engage with their healthcare providers; 56% found this usually easy, and 12% found it difficult.5 However, the report published no data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health literacy.

Since 2008, the life expectancy and infant mortality rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been a focus for improvement by the Australian Government.6 However, five of seven Close the Gap campaign targets identified for improvement (child mortality, school attendance, literacy and numeracy, employment and life expectancy) have either not been met, have no ‘agreed trajectory’ to measure progress against or have no published data.7 To achieve the campaign’s goals, it is necessary to promote autonomy and empowerment in healthcare decision making among this population group.8 Said plainly, they require sufficient health literacy to be genuinely involved in their own care. Unfortunately, the health literacy levels of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are poorly understood and insufficiently researched.9–11 This article discusses: 1) research regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health literacy, 2) availability of appropriate health literacy assessment tools and 3) implications for general practice.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health literacy

It is believed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health literacy is lower than that of non-Indigenous Australians.1 This is plausible given school-age Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lower literacy, numeracy and scientific literacy levels than non-Indigenous students.12,13 Some models of health literacy also include factors such as cultural literacy, navigating the healthcare system and finding good health information.14,15 These coexist alongside accessibility barriers, such as an individual’s ability to perceive, seek, reach, pay for and engage with healthcare.16 Thus, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples may encounter barriers to their health literacy regardless of their English proficiency.

Some research has provided insights into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health literacy levels. Rheault et al found that age <55 years, female gender and higher levels of education were factors associated with higher health literacy levels, while increasing age and chronic comorbid conditions were associated with lower health literacy levels.11 Smith et al reported that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men (aged 14–25 years) had ‘reasonable understanding of their health’ and were willing to address their health needs by seeking help and accessing medical services.17

Appropriate health literacy assessment tools

The RACGP recognises that low health literacy is common in Australia and that different communication strategies are required during patient consultations; however, it does not recommend a specific health literacy assessment tool.18 General practitioners (GPs) are thus given little direction in terms of which health literacy assessment tools, if any, should be used. Furthermore, there are more than 200 health literacy assessment tools available, yet none appear to be validated in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.9,19 Regardless, some tools have been used to assess the health literacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; for instance, Rheault et al used a verbatim spoken HLQ to assess health literacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with chronic disease living in remote areas.11 The HLQ is endorsed by the World Health Organization and is used in different cultures and settings including Australia, but its validity and reliability among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples remains unassessed.11 Smith et al instead used yarning (informal talk) with young (aged 14–25 years) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males following a discussion guide based on the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT).17,20 Yarning is recognised as a culturally appropriate research method that is used internationally with First Nations peoples.21 Appendix 1 summarises some health literacy tools used in Australian populations and their main features.

Implications for general practice

Even if validated health literacy assessment tools for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were available, the appropriateness of their use in general practice would be contentious, as routine health literacy screening has the potential to cause shame and alienation.22 Practitioners could instead consider single screening questions such as, ‘How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?’ or, ‘How often do you need to have someone help you when you read instructions, pamphlets or other written material from your doctor or pharmacy?’.23–26 Such questions are suitable for identifying individuals with limited health literacy but are weaker at identifying those with marginal health literacy.23,25 Additionally, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care recommends the ‘universal health literacy precautions’ method.1 This approach assumes all patients may have difficulty comprehending health information and accessing health services, and it prioritises patient education over assessing their health literacy.27 The approach encourages simplified communication with patients and regular confirmation of understanding. Examples of this approach include empowering patients to ask questions and using the teach-back method to confirm comprehension.28

It is important to identify the limitations of non-Indigenous practitioners when considering how best to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, regardless of their health literacy level. It is believed that Australian health professionals have an inadequate understanding of the consequences of low health literacy and limited knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ and communities’ health literacy.29 Australian general practice registrars should attend some formal cultural training, but this need not be formal study. Many GPs thus learn cultural awareness from supervisors or medical educators whose knowledge and experience may vary.30 Abbott et al found that supervisors and medical educators in a simulated consultation with an Aboriginal patient focused feedback predominantly on general consultation and communication skills.30 The authors also found that 28% of the participants did not refer to the patient’s culture or Aboriginality, and less than half provided teaching points specific to Aboriginal health, culture or ongoing learning.30 Inexperience, inadequate knowledge of culture and fear of mistakes may lead practitioners to avoid incorporating culture into their consultations, therefore affecting quality of care.30–32 Furthermore, this conceivably constitutes a cultural barrier to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients’ health literacy.

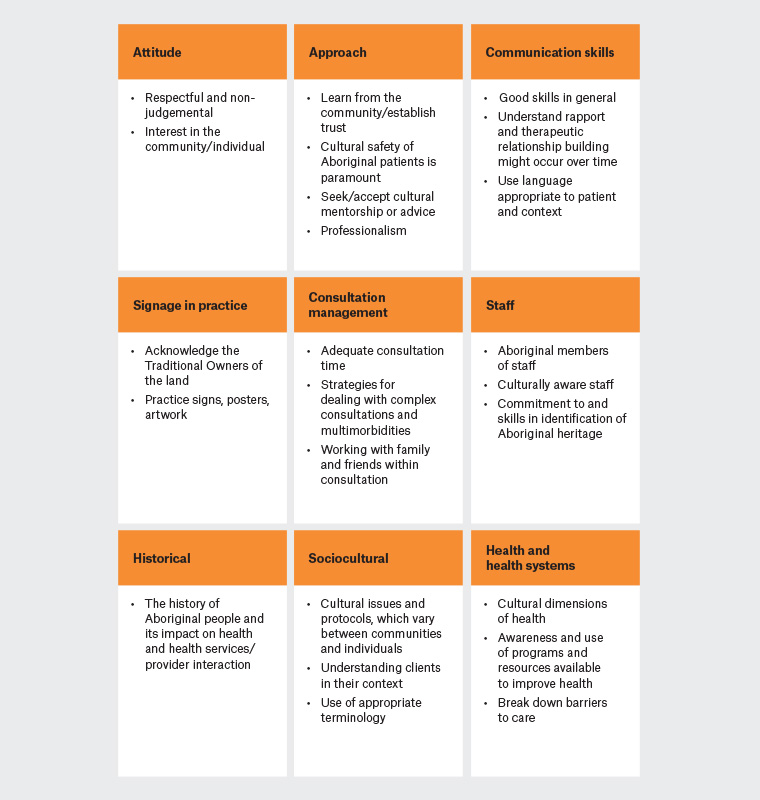

Incorporating culturally sensitive assessment methods such as CHAT/yarning questions into the annual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander preventive health assessment (Medicare Benefits Schedule Item 715) may have potential to improve the health of this population.33 For instance, the clinical yarning framework is designed to improve patient–practitioner communication using three conversational phases: social, diagnostic and management yarning.34 CHAT-based yarning questions provide another non-intrusive option (Table 1).17 Following interviews with Aboriginal people in cultural support or mentorship roles of GPs, Abbott et al recommended altered communication styles, being non-judgmental, expressing interest in the community, using appropriate terminology and being aware of programs and resources available to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients to satisfy some of the unmet needs of this population (Figure 1).35 Other recommendations are related to organisational health literacy, for example, displaying signage acknowledging a practice is on traditional land, Aboriginal posters or artworks. These steps assist in demonstrating a practice’s cultural sensitivity. Further changes to organisational health literacy could include simplification of written information and forms.36 A focus on teaching interactive and critical health literacy skills can develop patients’ capacity for self-management and support community empowerment.36 Unfortunately, studies of health literacy interventions are often low quality, hence firm recommendations for successful intervention strategies are lacking.36,37 Organisational changes may also encounter resistance within a practice. Resistance to change is natural and is manageable with clear goals and the provision of information justifying why changes are occurring.38

| Table 1. Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT) questions presented in combination with yarning |

| Topic |

Questions* |

| Understanding health contexts |

- What do you think are the key health issues facing young Aboriginal fellas and why?

- What can young Aboriginal fellas do to stay strong and healthy? How is this best achieved?

- How important is your cultural identity to your health and wellbeing, and why? (Probes: family ties, kinship, connection to Country, ceremonies, Elders)

- What influence do your family and friends have on your health? In what ways and why?

- What does the word health mean to you? Does it mean one or more things?

|

| Supportive professional relationships |

- Who do you usually see to help you look after your health?

- How difficult is it for you to speak with [that provider] about your health?

|

| Supportive personal relationships |

- Aside from healthcare providers, who else do you talk with about your health?

- How comfortable are you to ask [that person] for help if you need it?

|

| Heath information access and comprehension |

- Where else do you get health information that you trust?

- How difficult is it for you to understand information about your health?

|

| Supportive health programs and services |

- Which existing programs and services do you think work best for young Aboriginal fellas and why?

- Are existing programs and services targeting young Aboriginal fellas meeting their needs? How could local services better support the needs of these fellas?

- Do you think health services and programs for young Aboriginal fellas are culturally appropriate/safe?

|

| Current health behaviours |

- What activities do young Aboriginal fellas do that puts their health at risk or creates health problems? What would you do to change this and why?

- How do the behaviours of others (eg friends and families) influence your health (both positively and negatively)? How does this affect the decisions you make about your health?

- What do you do to look after yourself on a daily basis?

- What do you do to look after yourself on a weekly basis?

- If you could do one thing to help young Aboriginal fellas live a healthier life, what would that be?

|

| Health promotion barriers and support |

- Thinking about the things you do to look after your health, what is difficult for you to keep doing on a regular basis?

- Thinking about the things you do to look after your health, what is going well for you?

- How do you think health education for young Aboriginal fellas could be improved/changed?

|

| Life aspirations |

- What goals do you want to achieve in life and why?

- How important is your health in achieving these goals? (Probes: social determinants of health)

- If you are/were a father, what values and qualities would you like to see in your son/s and why? Do you have any of these qualities?

- Do you have any role models/figures in your life that display these qualities? If so, who and why?

|

*Questions are based on the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT); questions in bold are suggested for yarning.

Modified and reproduced with permission from Smith JA, Merlino A, Christie B, et al, ‘Dudes are meant to be tough as nails’: The complex nexus between masculinities, culture and health literacy from the perspective of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males – Implications for policy and practice, Am J Mens Health 2020;14(3). doi: 10.1177/1557988320936121. |

Figure 1. A practice guide for general practitioners providing care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Modified and reproduced with permission from Abbott P, Dave D, Gordon E, Reath J, What do GPs need to work more effectively with Aboriginal patients? Views of Aboriginal cultural mentors and health workers, Aust Fam Physician 2014;43(1):58–63.

Conclusion

The levels of health literacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples remain poorly understood, with the problem perpetuated by a lack of appropriate assessment tools validated for use in this population. Culturally insensitive screening of health literacy has the potential to disaffect; thus, practitioners should consider assessments aligned with Indigenous methodologies such as conversational or yarning approaches, or the use of 1–3 screening questions. Practitioners are encouraged to adopt a universal precautions approach and culturally appropriate conversational styles to optimise patient–practitioner communication and healthcare outcomes.

Key points

- Low health literacy results in poorer health outcomes and lower utilisation of health services.

- The health literacy levels of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are unknown.

- There are no health literacy assessment tools specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- Conversational, yarning or single question approaches to assessing health literacy may be most appropriate for use in this population.

- Identifying and supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with low health literacy using simple and culturally sensitive methods should be encouraged in general practice.