Disparities in cancer outcomes between rural and urban populations remain a global problem.1 Australia is not excepted to such rural–urban inequities.2 For breast cancer, women living in rural New South Wales (NSW) have worse survival rates compared with their urban counterparts.3,4 They are also more likely to have late-stage breast cancer upon diagnosis, longer diagnostic interval and higher risk of death.5–7 Improved cancer control to reduce rural–urban disparities rightly remains an important health priority.

Despite the high uptake of screening mammography in Australia, the majority of diagnoses are still made in women with non–screen detected breast cancers.8 For these women, the point of symptom detection up until their first clinical presentation represents the earliest time interval in the breast cancer pathway. This is defined as the ‘patient interval’ based on the framework proposed in the Aarhus statement – which is an international consensus statement to facilitate the standardised and uniform definition and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis.9 Identifying factors that prolong the patient interval is closely intertwined with what influences women to seek help for their symptoms once discovered, and a qualitative approach is well suited to explore this.

Numerous qualitative studies have investigated what influences help-seeking behaviour for such women across various international settings.10–18 A meta-ethnographic synthesis of these studies revealed eight common concepts that affected help-seeking behaviour: symptom detection, initial symptom interpretation, symptom monitoring, social interactions, emotional interactions, priority of seeking medical help, appraisal of health services and personal–environmental factors.19 However, these qualitative findings must be interpreted within the contexts that they were conducted in, considering related social and cultural issues for that sample group.

In the Australian healthcare system, the point of first presentation is most likely to be to a general practitioner (GP). There are few studies examining differences in help-seeking behaviours in patients with cancer across rural–urban Australia, with studies in rural Western Australia (WA) and Victoria presenting conflicting themes in terms of the presence of stoical responses for patients with cancer living in rural areas.20,21 A study examining the help-seeking behaviours of breast cancer patients in NSW had not been conducted.

The relationship between prolonged breast cancer pathways and poorer survival is well established,22 and identifying factors that prolong the patient interval and determining whether these factors are more common in rural areas could help facilitate the identification of targeted interventions to address the gaps in service delivery and reduce the disparity in breast cancer outcomes for people living in rural Australia.

Methods

Aims

The aim of this study was to identify and explore the differences in help-seeking behaviours between rural and urban women with non–screen detected breast cancer.

Design

We conducted a qualitative study consisting of semi-structured interviews with 20 women from NSW with non–screen detected breast cancer that was diagnosed within the past five years.

Setting and sample

A purposeful sampling frame was used to ensure representation from rural and urban NSW locations and from different age groups. Interviews were stopped once theoretical data saturation was perceived to be reached. Residential location at time of diagnosis was classified as rural or urban using the Modified Monash Model.23 Locations in Modified Monash (MM) categories 1 and 2 were classified as urban, and locations in MM categories 3–7 were classified as rural.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible participants were those living in NSW at the time of diagnosis and were diagnosed with non–screen detected breast cancer within the last five years. Those who were not able to provide informed consent or could not communicate in English were excluded

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via social media advertisements. Interested participants were directed to an online form that acted as an initial eligibility screening tool. They were then contacted by telephone to determine final eligibility and scheduling of an interview. A total of 42 women responded to the advertisements over the period of April to June 2021. Of these, 27 met the eligibility criteria and a total of 20 participants were interviewed. The main reasons for ineligibility were being diagnosed more than five years ago or not residing in NSW at the time of diagnosis.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by DF over a videoconference platform and averaged 20 minutes in length. Interviewing via videoconference was chosen due to restrictions across NSW because of the COVID-19 pandemic. DF is a GP registrar in regional NSW and an early career researcher undertaking this research as part of a formal academic training post under the supervision of JR. JR is a specialist GP with extensive experience in qualitative research, and research in healthcare decision making in people with serious illnesses.

Participants had no prior relationship with the interviewer. Interviews were guided by an interview schedule that began with an open question regarding the participant’s experience when the initial symptom was detected, followed by questions tracing the participant’s thoughts and actions leading up to their first presentation to their GP. Questions were informed by similar previous studies but not pilot tested.20,21 Field notes were made during and after each interview, with new points of interest being explored in subsequent interviews. This included prompts to clarify and confirm emerging themes as a form of member-checking. No repeat interviews were conducted.

Data analysis

All interviews were recorded to be transcribed verbatim via a professional transcription service. Transcripts were de-identified and double-checked for accuracy by DF. A qualitative descriptive approach, as articulated by Sandelowski,24 was chosen to identify and investigate key factors that influenced participants’ decisions to seek help for their symptoms. Transcripts were analysed line by line, and their content was examined and compared to assign codes that described what was interpreted in the passage as important. Codes were then grouped into categories that shared a commonality. Based on these emerging categories, themes and subthemes were generated through shared threads of meaning across categories. The data analysis process was iterative and occurred simultaneously with data collection. DF analysed all 20 transcripts, with JR independently reviewing two randomly selected transcripts. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved during regular meetings to enhance study rigour and improve reflexivity. All data were managed using the NVivo 12 Plus software.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong (2021/069) and participants provided both written and verbal informed consent.

Results

Participant characteristics

All participants were interviewed between April and June 2021. All participants were women. The mean age of participants was 51.5 years, ranging 37–72 years (standard deviation: 11.5; Table 1). Eleven participants were residing in a rural location at time of diagnosis and nine were residing in an urban location. Median time from diagnosis to interview was 18.5 months, ranging 3–48 months.

| Table 1. Participant characteristics |

| Characteristic |

n (%)* |

| Age in years |

| Mean (standard deviation) |

51.5 (11.5) |

| 36–40 |

5 (25%) |

| 41–45 |

2 (10%) |

| 46–50 |

2 (10%) |

| 51–55 |

5 (25%) |

| 56–60 |

1 (5%) |

| 61–65 |

2 (10%) |

| ≥66 |

3 (15%) |

| Residence at time of diagnosis |

| Urban |

11 (55%) |

| Rural |

9 (45%) |

| Time from diagnosis to interview: Median months (range) |

18.5 (3–48) |

| *Data presented as n (%) except for mean age and time from diagnosis to interview |

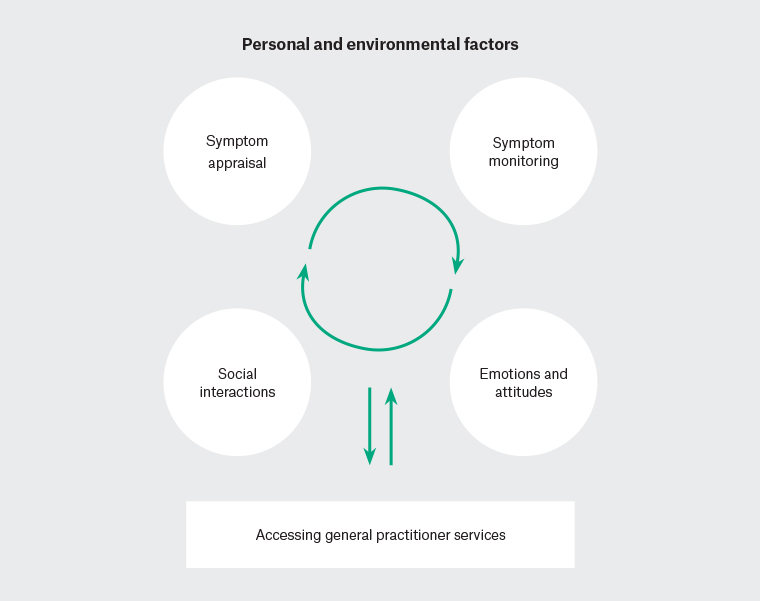

Overview of themes

Six key themes emerged from the data analysis, each encompassing a range of facilitators and barriers to help-seeking: 1) Initial symptom appraisal; 2) symptom monitoring processes; 3) emotions and attitudes towards symptoms; 4) social interactions; 5) personal or environmental factors; and 6) accessing GP services. These are further described below.

Theme 1: Initial symptom appraisal

Participants reported a period of initial symptom appraisal upon symptom detection. Women who perceived their symptoms to be something potentially serious were less likely to delay help-seeking, while women who perceived their symptoms to be benign in nature were more likely to self-manage and undergo a period of symptom monitoring. For both rural and urban groups, the outcome of this appraisal process was based on several common factors such as their perception of risk for breast cancer, previous history of benign breast conditions, having other plausible explanations for their symptoms, and their knowledge of potential breast cancer symptoms.

Perception of breast cancer risk

The perception of being high risk for breast cancer facilitated help-seeking behaviour. Most commonly, this perception stemmed from having a family history of breast cancer (Table 2, Quote [Q]1).

Women who perceived themselves as low risk for breast cancer tended to attribute a lower severity to their symptoms. This stemmed from being of a younger age, having no family history of breast cancer, a sense of being generally healthy, or having normal regular screening mammograms (Table 2, Q3–Q5).

History of benign breast conditions

Having a previous history of benign breast conditions resulted in a lower severity appraisal of detected symptoms, which acted as a barrier to help-seeking. A rural woman described how having a breast lump previously investigated influenced her decision to seek help as the symptom persisted (Table 2, Q6).

Other plausible cause to explain symptom

Some women attributed their symptoms to other plausible causes such as musculoskeletal strain or breastfeeding; these were described by both rural and urban women (Table 2, Q7–Q8).

Matching of knowledge to breast cancer symptoms

Detecting a breast lump was the most common initial symptom reported in this study. For women whose symptoms matched up with their knowledge of potential breast cancer symptoms, this prompted urgent action (Table 2, Q9).

Having a mismatch of symptoms with a woman’s knowledge was both a facilitator and barrier, depending on the symptom. A rural woman who experienced a painful breast lump had a preconceived notion that the presence of pain meant that it was not likely to be cancer. However, the pain itself prompted presentation to a GP for further assessment of other potential causes (Table 2, Q10).

Theme 2: Symptom monitoring processes

Once initial symptom appraisal was completed, women who had elected to self-manage underwent a period of symptom monitoring. Any change in the initial symptom or persistence of the symptom beyond a self-imposed time frame facilitated help-seeking (Table 2, Q11–Q12).

In contrast, women who perceived their symptoms as stable or had fluctuating symptoms tended to delay help-seeking further and continued an iterative process of symptom appraisal and monitoring (Table 2, Q13–14).

| Table 2. Exemplar quotes for themes 1 and 2 |

| Theme |

Subtheme |

Exemplar quotes |

| Initial symptom appraisal |

Perception of breast cancer risk |

Q1 |

‘I actually went to the doctors then to have it looked at, because of our family history.’ [Participant (P)4, 53 years, urban] |

| Q2 |

‘I’d always sort of thought I wasn’t in that age bracket. So I wasn’t really thinking it was anything sinister … I thought it was 50 and over really.’ [P16, 47 years, urban] |

| Q3 |

‘Because I was physically — you know, I was pretty fit … Like general health, I was well … I didn’t feel that there was an urgency for it.’ [P2, 65 years, rural] |

| Q4 |

‘I probably always thought that there was nothing wrong because I’d been quite well anyway … I don’t think there’s much cancer in our family at all. So it was probably like, oh, it shouldn’t be anything too bad.’ [P5, 37 years, urban] |

| Q5 |

‘You hear about that you need to have your mammogram, which I do, every two years … I didn’t think anything serious about it because I had this mammogram done 10 months ago, and I was thinking that if it would have been anything serious it would have popped up.’ [P10, 55 years, urban] |

| History of benign breast conditions |

Q6 |

‘Well, I actually wasn’t that worried about it because I had already had it checked out … I did almost cancel that appointment then because I just thought I was wasting my money.’ [P19, 38 years, rural] |

| Other plausible cause to explain symptom |

Q7 |

‘I don’t think I thought of breast cancer … I was breastfeeding at the time, my boobs were always kind of lumpy, so I just didn’t put two and two together … I just put it down as your boobs are lumpy when you’re breastfeeding.’ [P13, 38 years, urban] |

| Q8 |

‘I had soreness underneath my arm for quite a while but seeing that I had been doing farm work with fencing and cows and what have you, I just put it down to strain. … So, you just put it down to your doing heavy physical stuff all the time so you’re bound to get a bit of soreness somewhere along the line.’ [P18, 64 years, rural] |

| Matching of knowledge to breast cancer symptoms |

Q9 |

‘There is a lump in my breast, it’s got to be something … I knew I had to get on top of it. It’s something that I couldn’t ignore.’ [P11, 52 years, urban] |

| Q10 |

‘And it was quite sore, and I had heard that if you have a lump in your breast and it’s sore then that’s a good, you know, like it’s not always a bad lump … for me, the lump was actually quite painful … it was probably one of the reasons why I ended going to the doctor.’ [P12, 38 years, rural] |

| Symptom monitoring processes |

Change in initial symptom |

Q11 |

‘So I felt that it had changed – was getting bigger. It was sort of aching, changed the way the lump felt and that was probably August–September ’17 and that’s when I went to my GP.’ [P4, 53 years, urban] |

| Persistence of symptom |

Q12 |

‘I’ve kind of got a rule with myself that if I have symptoms for more than two weeks I’ll make an appointment and just get it checked out. So that’s my own, sort of, rule that if I have, yeah.’ [P3, 49 years, rural] |

| Perceived stability of symptoms |

Q13 |

‘I thought, I’ll keep examining myself, if it enlarges or it changed shape, in any shape or form, I’ll go and see the doctor. But, yeah, it just took a bit of time before it actually did that. But meanwhile, as I was examining myself, the lump always felt the same size.’ [P10, 55 years, urban] |

| Fluctuating symptoms |

Q14 |

‘It would come and go … it was just a pain on and off … four months later I continued to get the pain on and off and I wasn’t at all concerned. I just thought, okay, nothing there, it’s just hormonal.’ [P7, 44 years, rural] |

Theme 3: Emotions and attitudes toward symptoms

Women also reported that their emotions and attitudes toward their symptoms factored in their decision to seek help. Most women felt a general sense of urgency toward their symptoms, which prompted help-seeking. This sense of urgency was multifactorial in nature and was associated with how a woman felt about her initial appraisal of the symptom, personality traits and knowledge of having a better prognosis with earlier diagnosis (Table 3, Q15–Q17).

Attitudes such as feeling stigmatised, denial and stoicism acted as barriers to help-seeking. Denial and stigma featured in both rural and urban groups (Table 3, Q18–Q19).

The presence of stoicism was unique to the rural group. These rural women described a very high threshold for what would warrant a presentation to a GP (Table 3, Q20–Q21).

Theme 4: Social interactions

Social interactions played an important role in influencing help-seeking behaviour. Both rural and urban women reported receiving encouragement from their friends, family or colleagues to see their GP once they had shared their symptoms with that person or people (Table 3, Q22).

Having a social awareness about breast cancer also facilitated help-seeking. Women reported this in various forms, including having had a friend or family member experience cancer or through public health campaigns and local community events (Table 3, Q23–Q24).

Theme 5: Personal or environmental factors

Overarching personal or environmental factors had a significant impact on help-seeking behaviour. These factors mostly acted as a barrier to help-seeking. Many women reported having competing family or work commitments taking precedence over going to a GP about their symptoms (Table 3, Q25–Q26).

Women who detected symptoms during a holiday period were more likely to delay help-seeking. For urban women this was due to being away from home, and for rural women this was due to services being closed (Table 3, Q27–Q28).

Restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic had also acted as a barrier to help-seeking. A rural woman described becoming ‘despondent’ after being told she was not able to have a telehealth appointment at a practice she had previously been to more than 12 months ago (Table 3, Q29).

| Table 3. Exemplar quotes for themes 3, 4 and 5 |

| Theme |

Subtheme |

Exemplar quotes |

| Emotions and attitudes toward symptoms |

Sense of urgency |

Q15 |

‘I knew instinctively that I needed to get it looked at … Like I’m not someone that would put things off if I think they’re an issue.’ [Participant (P)13, 38 years, urban] |

| Q16 |

‘I think being a nurse, I’ve always been hyper-vigilant with any kind of symptom and I’ve gone to the GP with lots of little ailments, thinking that I was trying to get on to things early.’ [P20, 40 years, rural] |

| Q17 |

‘… from being like a health teacher, in a schooling environment, I pretty much knew that early detection is the best.’ [P8, 46 years, rural] |

| Denial |

Q18 |

‘I think a lot of people, probably like me, just don’t believe it’s going to happen to you.’ [P1, 59 years, urban] |

| Stigma |

Q19 |

‘You realise how many people in our area go through this quite silently, and you don’t even know that it’s happening. So I think it normalises it, but it also then, once you feel a symptom, would make you act on it quite quickly, yeah.’ [P12, 38 years, rural] |

| Stoicism |

Q20 |

‘I never saw a doctor really unless it was – I don’t know – if anything was gushing or bleeding bad … So something like that? No. For me? Nup … I don’t think I would have made such a big deal out of it. I just would have been – yeah, all right, whenever.’ [P14, 43 years, rural] |

| Q21 |

‘I certainly wasn’t thinking, you know, oh gosh, something is really wrong here … So I just put up with it and go, oh, once it’s gone, it’s the back of your mind … And that’s the same for everyone in my family. Like the kids have got to be pretty sick before I’ll go to the doctors.’ [P7, 44 years, rural] |

| Social interactions |

Encouragement from friends or family |

Q22 |

‘I did tell [my partner] when I found it initially … we were both on the same page, that it was really important to go to the doctor and get it checked … I do wonder if I didn’t say anything to [him], whether I would have actually done it or not. Definitely not as fast as I did’ [P5, 37 years, urban] |

| Social awareness |

Q23 |

‘I actually lost a good girlfriend of mine … and I had been through the process with her over the last four or five years – [otherwise] I possibly would have even shrugged it off even longer.’ [P12, 38 years, rural] |

| Q24 |

‘I just think with all the campaigning you hear, you hear a lot about breast cancer. I know the symptoms are a lump and I also felt a little bit of a lump under my arm … I just thought I’d just go and get some tests done anyway.’ [P16, 47 years, urban] |

| Personal or environmental factors |

Competing personal commitments |

Q25 |

‘As a mum, you put yourself last, everything else comes first … life was real busy. So a lot of my own health was not at the forefront.’ [P8, 46 years, rural] |

| Q26 |

‘I knew I should have gone immediately but as I said, I was really busy at work because I’d been away for three weeks … It was always just on the back-burner … I wasn’t in denial or putting it off or frightened or anything like that. I just couldn’t find the damned time to get there.’ [P17, 71 years, urban] |

| Holiday period |

Q27 |

‘I was actually going to England the very next day … I was on a holiday. … I wasn’t concentrating on it. That was something to deal with when I got back.’ [P17, 71 years, urban] |

| Q28 |

‘Like, all over Christmas and New Year. I’m walking around with this breast cancer and everyone’s shut, everything’s closed.’ [P15, 66 years, rural] |

| COVID-19 |

Q29 |

‘I reached out then to try and go to a GP that I had been to – I probably hadn’t been to that GP for 18 months … during COVID[-19], his receptionist had said, “Look, you’re not really classed as a patient here anymore because you haven’t been for this long”, and I was a bit despondent after that phone call. So I, kind of, then was annoyed and didn’t do anything about it probably for another week.’ [P12, 38 years, rural] |

Theme 6: Accessing GP services

How women interacted and accessed GP services was a vital factor in the decision-making process to seek help. There were significant differences between rural and urban women on their attitudes towards accessing GP services and the practical issues that they faced in the process.

Attitudes to accessing GP services

Both rural and urban women reported that having an established relationship with their GP was a major facilitator during their help-seeking process. Developing trust and having a GP that actively listens were key factors in building a good therapeutic relationship with their GP (Table 4, Q30–Q31).

Conversely, having a previous negative experience with a GP created distrust and acted as a barrier to help-seeking, either as a direct result of that experience or due to concerns about presenting unnecessarily. This was only reported by urban women (Table 4, Q32–Q33).

Many women had specific GP preferences, and both urban and rural women preferred to see a female GP for their breast symptoms. An urban woman described how she had to ring three practices before being able to get an appointment with a female GP (Table 4, Q34).

Some rural women described being reluctant to see a new GP or a bulk-billing GP. These attitudes were not represented in the urban group (Table 4, Q35–Q36).

Practical issues accessing GP services

Rural women reported significantly more practical issues with accessing GP services. In fact, no urban women reported having any practical issues with accessing such services. The majority of these issues acted as barriers to help-seeking. One rural woman described how her GP was doing telehealth appointments even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which facilitated her access to her GP despite living a significant distance away (Table 4, Q37).

Many rural women were frustrated at the lack of availability of their regular GP and having to choose between a longer waiting period or having to see a GP who was unfamiliar to them (Table 4, Q38–Q39).

The cost of seeing a GP and having to travel long distances were also significant barriers for some rural women (Table 4, Q40–Q41).

| Table 4. Exemplar quotes for theme 6 |

| Theme |

Subtheme |

Exemplar quotes |

| Accessing GP services |

Established relationship with general practitioner (GP) |

Q30 |

‘I trust my doctors and I feel I have that relationship with them … I think that that’s part of it, is the relationship that you’ve built with your doctor, that you feel that you’re going to be listened to … I’m a bit frightened of going to the doctor, but I trusted them and I knew that good, bad or ugly, that they’d be there and give me the appropriate support, that they’d take my concerns seriously.’ [Participant (P)4, 53 years, urban] |

| Q31 |

‘I have a really good relationship with my GP and I don’t know what made me say it. Usually I, probably, wouldn’t have thought about it. But I just thought — I think she probably prompted, “Oh, is there anything else?”’ [P3, 49 years, rural] |

| Previous negative experience |

Q32 |

‘I was a bit concerned because of what happened 12 months before, that the doctor just shoved it aside. So I didn’t want to see that doctor again, and I hadn’t had a regular GP at that point in time.’ [P5, 37 years, urban] |

| Concerns about unnecessary presentation |

Q33 |

‘So that when it is normal, or they think that there’s something wrong, that they act promptly, but then, to be reassured that when they go to the doctor as a 20-year-old, that the doctor is actually going to take them seriously and not fob them off.’ [P4, 53 years, urban] |

| Preference for female GP |

Q34 |

‘I tried another practice and there was no women on. … So, because the third practice that I tried, and as I said, yeah, just got on to — the only lady I could get in to see … I’ve seen male doctors in my life, but I think because it was breast cancer, I just really thought I needed to see a woman for that.’ [P1, 59 years, urban] |

| Reluctance to see new GP |

Q35 |

‘I probably didn’t feel comfortable just going to any doctor somewhere else, because they didn’t have my history.’ [P6, 52 years, rural] |

| Reluctance to see bulk‑billing GP |

Q36 |

‘I don’t go to them [bulk-billing medical centres]. I’ve got a doctor that I like. I think she’s really good. So I don’t mind paying for her services when I need to go.’ [P7, 44 years, rural] |

| Telehealth |

Q37 |

‘Because I’ve known him for a long time and he knows us quite well, he’s been our family doctor for over 20 years … so he will do it [appointments] over the phone. That was even before COVID[-19] hit. Because he understood where we lived, which was great.’ [P6, 52 years, rural] |

| Lack of availability of regular GP |

Q38 |

‘Well, that’s quite common here in rural. The shortage of doctors in rural is – and if your doctor gets sick or has to have their own family’s need, it’s quite often that you’ll have to either wait for a month or so or maybe two months or see a locum that might have an available position. But most of the time it’s like six weeks with just normal, general healthcare. Even with my husband with a long history of medical illnesses, it’s six to eight weeks before he can get an appointment with his GP. So that’s the sad part of it.’ [P18, 64 years, rural] |

| Q39 |

‘Definitely availability and that is a little bit of an issue in our area where with some doctors … having that availability to a constant doctor is tricky in our area.’ [P12, 38 years, rural] |

| Cost to see GP |

Q40 |

‘And that, basically, comes down to the cost … I need to make sure I’ve got $80 and then you get whatever back … But if it’s a long consult, I think it’s like, 100 or something … I mean, we’re not poor, but I just don’t have an extra 100 bucks a week to waste on doctor visits.’ [P7, 44 years, rural] |

| Distance to GP |

Q41 |

‘Then you’ve the cost. You’ve got the transport cost as well as the gap fees and everything that you do. That’s huge in that, you know, can I afford it at the moment?’ [P18, 64 years, rural] |

Discussion

This study adds to the existing evidence on the help-seeking behaviour of women with breast cancer. We focused on the differences between rural and urban women within NSW, and how this impacted on early presentation to a GP. Our study indicates that the decision-making process to seek help once a symptom was detected is a complex, iterative and non-linear process affected by overarching personal and environmental factors eventually leading to a decision to present to a GP. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Both rural and urban women described similar concepts within the themes of symptom appraisal, symptom monitoring, social interactions and personal and environmental factors. This similarity between the two groups is consistent with previous Australian studies of rural women in WA and Victoria.20,21 Ensuring that women have up-to-date knowledge of their personal risk, the potential symptoms of breast cancer, and encouraging early presentation especially if a symptom is ambiguous, are key to addressing the barriers within the symptom appraisal and monitoring processes.

Figure 1. Decision-making process to seek help

Stigma and denial were prominent barriers that featured across both rural and urban groups. Many women reported that having an increased social awareness from social interactions and exposure to public health or local community awareness campaigns were helpful in addressing these barriers. Our findings also indicate that having an established and trusted relationship with a GP creates an environment where women do not feel stigmatised or concerned about unnecessary presentations. This had strong influence on facilitating early presentation and reflects the importance of the longitudinal relationships that GPs develop with their patients and how maintaining continuity of care plays a key role in preventive medicine. GPs are in prime position to fill in potential knowledge gaps, address common misconceptions and normalise help-seeking for potential breast cancer symptoms. This in turn could help shift priorities for women who have many competing family and work commitments as well.

Our study found that stoicism was a barrier to help-seeking unique to the rural group. This contrasts with research in rural Victoria21 and supports findings from rural WA20 that a distinct set of rural attitudes may well contribute to delay in the help-seeking process. ‘Rural stoicism’ is thought to be a quintessential characteristic of the rural Australian character25 and it has been postulated that such stoicism contributes to poorer cancer outcomes for rural Australians.26 Our study adds further evidence to support this line of inquiry. How best to address this barrier remains to be determined; a randomised controlled trial in rural WA found that both community-based symptom awareness programs and general practice–based educational interventions had little impact on reducing time to diagnosis.27 Future research will be required to determine the strength of this effect and identify effective interventions to improve time to diagnosis and cancer outcomes for rural Australians.

There were significant issues regarding access to GP services for rural women pertaining to availability, cost and distance. This is in keeping with national data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics28 and is likely a reflection of the skewed distribution of the primary care workforce towards metropolitan areas.29 In addition to the current measures in place to increase the primary care workforce in rural Australia, ‘continued substantial investment coupled with ongoing evaluation and enhancement of rural and remote training programs’ will be critical to address this rural–urban disparity.30

Limitations

This was a qualitative study with a relatively small sample size and findings from this study may not be generalisable to other communities across Australia. We also acknowledge that rural communities are not homogenous in nature although they were represented as a single unit in this study. DF interviewed all participants; being a male with no lived experience of breast cancer, we acknowledge that this may affect participants’ responses given that breast cancer mainly affects women. It is also acknowledged that interviews over videoconference removes the ability to pick up on certain social cues and has significantly different dynamics to that of face-to-face interviews.

Conclusion

The decision-making process to seek help once a symptom was detected was a complex, iterative and non-linear process affected by overarching personal and environmental factors eventually leading to a decision to present to a GP. There was little difference between rural and urban groups in terms of symptom appraisal, symptom monitoring, social interactions and personal and environmental factors. The presence of stoicism was unique to rural women as a barrier to help-seeking. Rural women also faced significant barriers regarding accessing GP services pertaining to availability, cost and distance.