Infantile colic is a benign, self-limiting condition and is a common problem during early childhood, affecting approximately 20% of all infants worldwide.1–14 Symptoms peak around the sixth week of age, with symptoms ceasing naturally after 4–6 months of age.2,4,6–10,12,13 According to Rome IV criteria, the diagnosis of infantile colic requires all of the following: infant under five months of age when the symptoms start and stop; periods of recurrent and/or prolonged crying, agitation and irritability reported by caregivers, which occur without any obvious cause and cannot be prevented or resolved by caregivers; and absence of infantile failure to thrive, fever or illness.2,4–6,9,12,13 Despite infantile colic being a benign and self-limiting condition, it is important for the physician to be aware of potential warning signs that could indicate a pathological nature to the clinical presentation, such as fever, prostration, vomiting, diarrhoea and suboptimal growth velocity rate.2

Several aetiologies have been proposed: psychosocial causes (caregiver anxiety, insufficient caregiver–child relationship, or child of difficult temperament), immaturity of the nervous and digestive systems, changes in gut microbiota, and inflammation of the gastrointestinal system. The possibility that infantile colic occurs because of changes in gut microbiota leads to curiosity about the efficacy of probiotics.1,2,4‑6,8‑12,14,15

The inability to calm a child’s cry can be stressful for a caregiver who believes they are failing to provide adequate care, resulting in frustration, depression, deterioration or postponement of the establishment of the caregiver–child relationship and, in the worst-case scenario, child abuse. Caregivers of infants with colic often turn to healthcare professionals for help. When not adequately helped or enlightened, they may actively pursue alternative methods, most of them lacking scientific evidence and potentially unsafe. As an approach to colic, it is important that the general practitioner tries to relieve symptoms to reduce the impact on the family dynamics and the future relationship of the caregiver or parents with the child.1,2,4,6–9,13,14

Intestinal microbiota

It is suggested that intestinal colonisation begins in utero.16 The initial intestinal microbiota is composed of facultative anaerobes such as Staphylococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae spp. and Streptococcus spp. Several individual factors are known to influence the intestinal microbiota, particularly the type of delivery and the type of feeding (Table 1). Changes in the intestinal microbiota can lead to the appearance of intestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, bloating and flatulence).2–5,8,10–12,14 Studies have reported that children with colic have higher levels of proteobacteria (Escherichia coli) and lower levels of Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. when compared with healthy infants.3,5,6,10,11,15,17,18

| Table 1. Individual factors known to influence intestinal microbiota16 |

| Vaginal delivery |

Caesarean |

Formula-fed infant |

Breastfed infant |

| Similar to the mother’s vagina (Lactobacillus and Prevotella spp.) |

Similar to the mother’s skin (Streptococcus, Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium spp.) |

Higher concentration of Escherichia, Veillonella, Enterococcus and Enterobacter spp. |

Higher concentration of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp. (compared with formula-fed) |

Probiotics

Probiotics are defined as microorganisms that have scientific evidence of safety and efficacy.16 Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 is the most studied probiotic strain for infantile colic, followed by other strains of Lactobacillus spp. and strains of Bifidobacterium spp. All the probiotics strains studied for infantile colic were safe and well tolerated in healthy infants.18

The objective of this evidence-based review is to summarise the evidence of the effectiveness of probiotics in the treatment of infantile colic.

Materials and methods

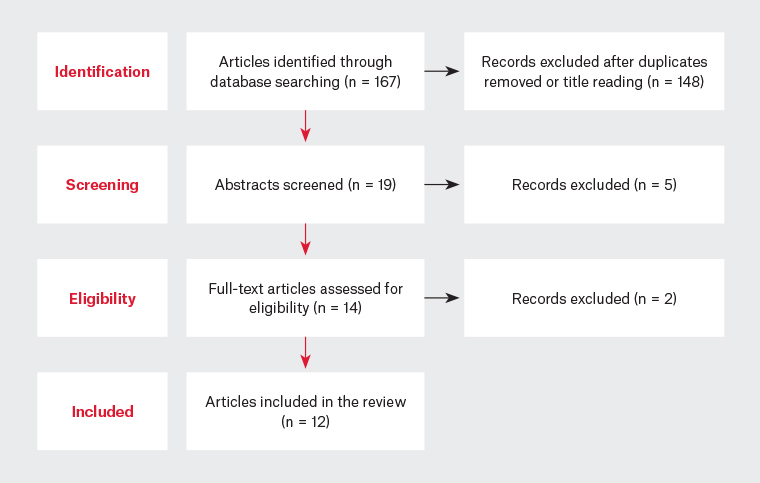

Pubmed, UpToDate and Cochrane Library were searched in August 2021 for articles published during the past decade regarding the treatment of infantile colic with probiotics applying the MESH terms ‘infantile colic’, ‘infant colic’ and ‘probiotics’. Included in this review were original studies, narrative reviews and systematic reviews written in English. Studies were excluded if they focused on infants over six months of age or infants with a diagnosis other than infantile colic (Figure 1). To better assess the evidence levels and attribution of recommendation strengths, the strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) scale was used.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the evidence-based search and review process

Results

Lactobacillus spp.

The evidence found on Lactobacillus spp. leads to the belief that a low intestinal concentration of Lactobacillus spp. has an important role in the pathophysiology of infantile colic. L. reuteri DSM 17938 is the most studied probiotic for infantile colic and is supported by the strongest evidence in the treatment of infantile colic and reduction of its symptoms (decrease in crying time and fussing).1–5,11,12

Moreover, L. reuteri DSM 17938 reduces pain perception through two pathways: via the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channel, influencing potassium-dependent calcium channel activity;2,5 and a reduction in capsaicin- and distension-evoked firing of spinal nerve action potentials.6 In addition, a reduction in anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria (Enterobacteriaceae spp. and Enterococci spp.) was verified.16 One study reported the ability of L. reuteri to inhibit the growth of glycogenic forms of gas in the intestine.14 Some studies observed a reduction of faecal calprotectin (an intestinal marker of inflammation) with L. reuteri DSM 17938.4,6

There are several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) purporting to the use of L. reuteri DSM 17938 as a treatment for infantile colic (Appendix 1). These RCTs took place in Australia, China, Canada and Europe (Italy and Poland). On the twenty-first day of treatment, most studies found a reduction of approximately 50% in crying time and fussing in the intervention group when compared with the placebo group. However, the Australian study, which had the largest sample size, did not find a significant difference between intervention and placebo. Theories emerged to justify these results, such as it being the first study to also include formula-fed infants, and that intestinal microbiota may differ across and within different countries. A meta-analysis of four high-quality double-blind trials presenting a total sample of 345 infants (174 probiotic/171 placebo) noticed a reduction in daily crying of 25 minutes from baseline by the 21st day in the probiotic group when compared with the placebo group. In addition, infants in the probiotic group were more likely to have treatment success than those in the placebo group, showing greater reduction in crying and/or fussing duration. It is also important to note that the authors of the meta-analysis considered that there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions in formula-fed infants with colic.1–4,6,7,11–13,19,20

In essence, the treatment of infantile colic with L. reuteri DSM 17938 at a dose of 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/day significantly reduces crying time in infants who are predominantly breastfed and offers a superior treatment in comparison to placebo and other therapies (diet, manipulative interventions, reassurance, massage, herbal treatment, acupuncture and simethicone).6,13,14,19, 20

Regarding the Lactobacillus family, there were two trials that used the L. rhamnosus GG strain, but there was no symptomatic improvement when compared with the placebo group (although parental report of crying suggested that the probiotic intervention was effective).18 Therefore, it is important to emphasise that the positive results of one strain do not necessarily imply the same effects using other strains.

Bifidobacterium spp.

Breastmilk contains commensal, mutualistic and/or potentially probiotic bacteria for the infant gut, including the B. breve strain, which becomes the dominant species in the intestinal microbiota of breastfed infants. B. breve colonises the newborn’s intestine, protecting it against infections, and plays a major part in the maturation of the immune system.16

The effect of B. breve B632 as a probiotic was verified in vitro by inhibiting the growth of Enterobacteriaceae spp. in a model that simulated the intestinal microbiota of an infant with colic aged two months.16 Another study observed the percentage of children who cried more than three hours per day, with this value being lower in the group treated with B. breve CECT7263 (12% of children) when compared with those treated with L. fermentum CECT5716 (21%) and the control group (29%). In this trial, B. breve CECT7263 showed a greater efficacy in decreasing the daily crying time in both breastmilk-fed and formula-fed infants. At the same time, the B. breve CECT7263 strain was associated with an intestinal anti-inflammatory effect, which could be considered relevant as it suggests that infantile colic can be associated with a systemic low-grade inflammation.18

Another Bifidobacterium strain (Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12), when provided alone, reduced the daily crying mean value in infants with colic.8,18

It should also be noted that there have not been many clinical trials performed evaluating the effectiveness of the use of Bifidobacterium spp. in infantile colic.

Mixture of probiotics

One study combined L. rhamnosus GG with another strain and found that this mixture had no effect on infantile colic symptoms. Conversely, a symbiotic product containing L. rhamnosus, L. reuteri and B. infantis probiotics and fructo-oligosaccharide showed efficacy on the seventh day of treatment.14

The aim of most of the studies was to understand the effect of isolated strains on the treatment of infantile colic. The effects of mixing different strains of probiotics could not be predicted from the results of using a single strain.

Guidelines

There are several guidelines on the treatment and management of infantile colic that recommend supplementation with L. reuteri DSM17938 in exclusively breastfed infants, such as the Northern America and Irish guidelines.13 In contrast, in the UK guideline and the clinical practice guideline from Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, it is noted that there is limited evidence to support generalised probiotic use, with only L. reuteri DSM17938 having evidence of efficacy in exclusively breastfed infants.13,21

Conclusion

Infantile colic is distressing to parents whose infant is inconsolable during their crying episodes. The physician’s role is to exclude a pathological cause for the complaints, offer evidence-based treatment and advice, give support to the family, and assure the parents that their child is healthy. The evidence needed to support the use of probiotics for infantile colic is limited and still emerging. L. reuteri DSM 17938 offers positive results in exclusively breastfed infants, and B. breve CECT7263 has shown efficacy in both breastfed and formula-fed infants. Of note, there have been no reports of adverse effects in all the trials performed thus far. More studies with larger samples and different variables (population from different countries and different feeding types) are required to obtain a better understanding and greater evidence of when and how probiotics can be used in the treatment of infantile colic.

Key points

- There is a growing belief in the scientific community that probiotics could be a safe and effective treatment for infantile colic.

- Several studies have concluded that L. reuteri DSM17938 was effective in exclusively breastfed infants with colic.

- There was insufficient evidence to make conclusions of the effectiveness of probiotics in formula-fed infants with colic.

- More studies with larger samples and less bias are needed.