Learning in the medical workplace is a complex process that includes apprenticeship learning, role modelling and construction of knowledge.1 Internship, or prevocational training, is a formative period intended to provide graduate medical students with a transition to clinical work and further training, to provide a general foundation of knowledge and skills prior to specialisation and to enable an informed choice for a career.2 Internship is therefore a crucial period of learning for medical graduates during which career decisions are often made.3

Interns are the most junior members of the medical workforce. They spend a relatively short time with each clinical team, which makes for a unique learning experience.

Internship has a curriculum. For instance, in Australia, the Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils4 has listed five key aspects of the Australian Curriculum Framework for interns. These are clinical management, professionalism, communication, clinical problems and conditions, and skills and procedures. However, the evidence on what interns actually learn during internship is sparse.

Supervision is an essential component of internship and is undertaken by hospital consultants and general practitioners (GPs).5 Good supervision is necessary for learning,6 particularly in general practice settings, where the role of the supervisor is considered paramount.7 Supervision enables junior doctors to undertake more complex clinical activities.8 However, types of supervision vary widely, and there are no clear standards for what is expected of supervisors.5

A safe learning environment is fundamental to the learning process for junior doctors.9 This learning environment has been described by Hafferty10 as consisting of three interrelated spheres of influence. These are:

- the stated, formal and endorsed curriculum (openly available and publicised)

- the informal curriculum, which is the unscripted, mostly ad hoc interpersonal form of teaching and learning that occurs between the faculty and students

- the hidden curriculum (influences of organisational structure and culture).

It is therefore recognisable that interns learn much more than what is taught formally in the clinical workplace. The importance of role models at all levels of medicine, and perhaps more crucially during internship, is also revealed, as junior doctors are often influenced by them when making career choices. It is important that medical educators recognise that the cultural and moral make-up of their training spaces are intimately involved in constructing what is right and what is not right in medical practice.10 Kendall and colleagues highlighted the importance of a positive learning environment, which is enhanced when junior doctors feel valued and supported by the team but is damaged when they do not feel supported.11 The authors of this study were alluding to the informal and hidden curriculum that is experienced by the learner.

A positive learning climate is also important for a junior doctor’s work-related wellbeing.12 It is also well known that junior doctors experience bullying in the workplace and that very few report it because of factors such as fear of reprisals and impact on one’s future career opportunities.13,14 When junior doctors feel supported, they are likely to enjoy their work and learn more.12

Several authors have recommended that current approaches to prevocational training need review.15–18 Furthermore, in 2015, a major review of medical internship undertaken in Australia reported structural deficiencies in the current internship model, which provided limited exposure to the full patient journey and range of patient care needs. The current model was also criticised for inadequately shaping graduates’ career choices. The quality and type of supervision were inconsistent, and the assessment process focused more on underperformance than on providing meaningful feedback.2,19

The aim of this study was to further examine aspects of learning during internship and had three objectives: 1) to ascertain what interns learned during internship, 2) to determine who they learnt from and 3) to describe the type of environments that influenced their learning.

Methods

Qualitative approach

This qualitative study adopted a qualitative description approach.20, 21 Qualitative description aims to ‘present a rich, straight description of an experience or an event’.22 When employing this approach, the researcher avoids excessive interpretation by staying close to the data.20 The approach therefore presents rich information that may be grounded in cultural and environmental contexts.

Theoretical framework

This study was underpinned by Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, which is one of the foundations of constructivism that has rarely been applied to apprenticeship learning in clinical settings. Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) was a Russian psychologist whose theory is one of the foundations of constructivism. According to Vygotsky, learning and development is a social process during which learners ‘grow into the intellectual life of those around them’.23

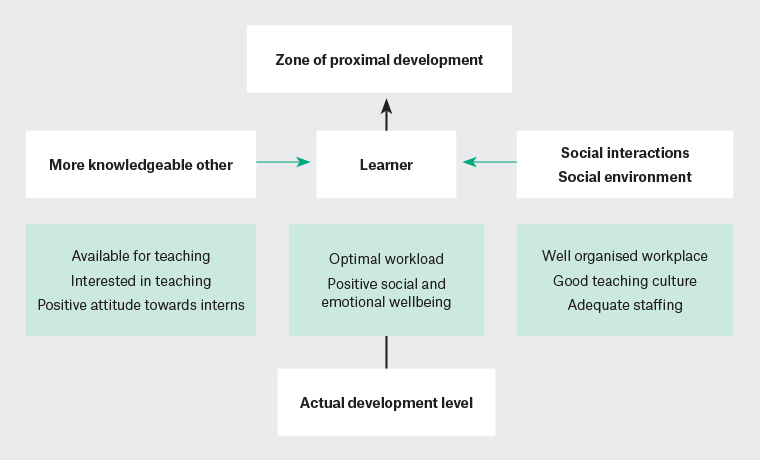

Vygotsky argued that there were two levels of development necessary to understand the learning process: The actual developmental level that the learner is at, where they can understand or do something without the assistance of someone more knowledgeable than them; and the ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD), which refers to what they can do with the guidance of a ‘more knowledgeable other’ (MKO).24 Therefore, the MKO not only supports the learner but also provides them with a scaffold of knowledge and skills. When the learner internalises this knowledge and skills, they move from their actual developmental level to the ZPD, thereby gaining autonomy – the ZPD therefore becomes their new actual developmental level.24

Vygotsky also believed that the social environment was critical for learning and argued that social interaction played a fundamental role in the development of cognition.25 If Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory were applied to learning during internship, then it would mean that a medical graduate learns during internship by building on their prior knowledge and skills to reach the ZPD when they are taught by MKOs in a sociocultural environment that is conducive for learning.

Reflexivity

The researchers, ANI (male) and BAS (female), are medical doctors. ANI is an experienced qualitative researcher. He teaches medical students and mentors novice medical researchers. BAS is a third postgraduate year (PGY3) registrar and is working towards an academic career alongside training in intensive care medicine. A key impetus for this research was the authors’ research and practical experience of the learning challenges experienced by interns.

Sampling and recruitment

An advertisement to participate in the study was placed on Facebook by BAS. Those who expressed an interest by replying to the advertisement were sent the explanatory statement and consent form, which contained details of the voluntary nature of participation, the anonymous nature of data collection and the freedom to withdraw at any time. Owing to the clear and narrow focus of the study, a large sample size was not considered necessary to answer the research questions. Those who returned a signed consent form with their telephone number listed were contacted to be interviewed. As a result of the time-bound nature of the study, recruitment of participants could not be extended.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by BAS using questions developed according to Vygotsky’s theory of learning. The questions were:

- In your opinion, what are the important things you learnt during internship? (New knowledge gained or ZPD)

- Who influenced your learning? (MKO)

- How did you learn? (Method of learning)

- What factors influenced your learning and how? (Social environment/social interactions)

- What situations made learning easier? (Social environment/social interactions)

- What situations made learning difficult? (Social environment/social interactions)

All participants gave informed consent to participate in the study. All interviews were conducted either in person (face to face) or by telephone and were digitally recorded during the months of March and April 2020. Audio files were given an anonymous code that included a serial number and letter that denoted gender (eg 10F). Coded audio files were then professionally transcribed.

Data analysis

Initial analysis was conducted by both researchers separately. Analysis commenced with reading and rereading each transcript. Discrepancies between the transcript and the audio recording were corrected. Once the researchers were familiar with data from each transcript, thematic analysis was applied.26 Accordingly, portions of data were initially assigned codes. Codes were refined and finalised either by combining, separating or renaming them to ensure that they accurately reflected the data they represented. The researchers then came together to discuss codes. Similarities and connections between codes were identified. Codes were then classified into four predetermined categories27 developed according to Vygotsky’s theory. They were: ‘new knowledge gained’, ‘more knowledgeable other’, ‘method of learning’ and ‘learning environment’. These codes corresponded to the ZPD, MKO, the support, and scaffold of knowledge and skills provided by the MKO and the conducive environment of learning, respectively. Categories were further analysed to look for subcategories.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID: 21937 dated 22/11/2019).

Results

Twenty participants were recruited for the study. Fifteen were female, and five were male. All were in PGY2–6 in an Australian health service. Participants were distributed across four different Australian hospitals (two metropolitan and two regional). Thirteen were aged between 25 and 29 years, six were aged between 30 and 34 years, and one participant was aged between 35 and 39 years. Fifteen participants were in PGY3, two were in PGY4 and one each was in PGY2, PGY5 and PGY6. Interviews ranged between 15 and 42 minutes in duration. Almost all initial codes were able to be classified into one of the four predetermined categories. The learning environment category was further divided into favourable and unfavourable learning environments. Codes and representative quotes have been presented in Tables 1–3.

| Table 1. Codes and representative quotes for categories ‘new knowledge gained’ and ‘more knowledgeable other’ |

| Categories |

Codes |

Representative quote |

| New knowledge gained |

General introduction to the healthcare system |

‘I don’t really know how to phrase this, but how the medical “system” works ...’ [01F] |

| Assessment and diagnostic skills |

‘I probably learnt a little bit about the acute assessment of major presenting complaints, like abdominal pain, chest pain, limb pain post trauma.’ [07F] |

| Medications and their dosages |

‘Learning to be comfortable charting medications and administering medications and those sorts of things.’ [08F] |

| Procedural skills |

‘I learned skills such as suturing, plastering, using the slit lamp for eye examinations in the emergency department.’ [04F] |

| Management of critically ill patients |

‘Patient deterioration management, how to manage MET calls, how to escalate and the disposition of the patient.’ [06F] |

| Calling for help |

‘I’d say the next biggest thing that I learnt, also non-clinical, would have just been asking for help and making sure that the right people were around.’ [03M] |

| Hospital clerical skills |

‘How to write charts. How to do discharge summaries. How to make good referrals.’ [17F] |

| Working as part of a team |

‘I guess that [what] I found was quite important was less medical but more learning how to work in a team.’ [11M] |

| Communication |

‘Communicating effectively with patients and their families as well as general practitioners … so trying to learn the different styles of communication you need for different patients as well.’ [05F] |

| Time management |

‘I’d probably say the most important non-clinical thing I learnt was time management. You get given lots and lots of jobs, working out what was a priority and how to get them done quickly …’ [03M] |

| Resilience |

‘How to look after yourself.’ [17F] |

| More knowledgeable other |

Registrars |

‘I say junior registrars in particular because they often were only a couple of years out from their internship …’ [03M] |

| Nurses |

‘I think you learn more from the nursing staff than you do from the doctors.’ [01F] |

| Co-interns |

‘… like a co-intern … just a little bit here and there.’ [12M] |

| Nurse educators |

‘… a nursing educator to get hands on with you, and it’s often just more practical opportunities in that role.’ [03M] |

| MET team |

‘I learned through exposure through multiple MET calls. I learned a lot from [them] …’ [06F] |

| Pharmacists |

‘… and the pharmacists they are all very useful people.’ [05F] |

| Consultants |

‘The main consultants that I worked with during my emergency rotation … watching them take histories when they saw my patients.’ [07F] |

| F, female; M, male; MET, medical emergency team |

| Table 2. Codes and representative quotes for the category ‘method of learning’ |

| Codes |

Representative quotes |

| Copying behaviour of seniors |

‘You take your senior doctor’s opinion as being “that’s how you do it”. And that’s how you learn … that’s what they do, so that’s what you do.’ [01F]

‘As an intern you’re observing so much. You’re observing how this person operates and how they treat others.’ [15F] |

| Learning by repetition |

‘And then it’s really just like the repetition as well of those skills that makes you good at it because you just have to do it, like all day, every day pretty much.’ [14F] |

| Through feedback |

‘People being willing to give you feedback as you go. I think that’s really important and I don’t know if that’s done enough, so the few times that people did that, it was really helpful … to constructively give good feedback as we go because I think that’s how we could learn much better.’ [15F] |

| Senior doctors’ teaching |

‘“Come and examine this abdomen” or “Have a look at this hernia” if you’re in clinic, like kind of just doing it on real patients in an informal setting; I think that’s probably the learning style that helped me to learn the best.’ [14F] |

| Organised teaching |

‘The effectiveness of the formal teaching is very topic dependent. It is also very presenter dependent.’ [06F] |

| Peer learning |

‘Yeah my co-resident on my renal rotation, which was my second rotation taught me most things I know about how to work on a ward. She showed me my way a little bit at a time.’ [17F] |

| Learning the hard way |

‘Well, you have to learn to be resilient by just dealing with the dead and dying patients on the medical ward late on a Friday night because there are no registrars around so it’s just you and your fellow intern; you just have to learn to kind of suck it up and get on with the job.’ [19F] |

| F, female; M, male |

| Table 3. Codes and representative quotes for the categories ‘favourable learning environment’ and ‘unfavourable learning environment’ |

| Category |

Codes |

Representative quotes |

| Favourable learning environment |

Well organised and staffed workplace |

‘… they weren’t stressed beyond measure. So we could have this dedicated teaching during the day. So it partly comes back to organisation and staffing, it’s just such a different amazing environment when you have that.’ [10F] |

| Teaching-oriented environment |

‘When you want to be there, you want to take part in it because people are there to support that learning. So, having not just your direct boss doing teaching, but also the nursing staff, the pharmacist on the ward, just everyone who’s there to facilitate that. That really helped me.’ [10F] |

| Passionate teachers |

‘I’ve got no desire to ever get involved in orthopaedics. And we had a lecturer that was teaching us musculoskeletal anatomy. By the end of it, I was like, “I could so do this … (laughing)”. It was ridiculous! Clearly never wanted to do it, but he was so passionate.’ [01F] |

| Approachable teachers |

‘When you’ve got someone who’s a bit more approachable, you don’t feel like an idiot asking … “We gave this person … and now it’s like… what should we do?”’ [08F] |

| Feeling supported |

‘I did feel really well supported there. Sometimes I did feel a bit like a medical student again because I was so well supported but I think that it was really good.’ [05F] |

| Feeling confident, and safe |

‘If we feel safe and confident, that enhances our learning … It’s that aspect of feeling safe around them; that they’re not going to yell at you; they’re not going to think you’re incompetent but they understand that you need to learn.’ [15F] |

| Unfavourable learning environment |

Overworked and understaffed |

‘It was just hard to learn because everyone is so overworked; their department’s so understaffed. You can’t actually ask anyone; you can’t get anyone on the phone. So it was very difficult to learn anything …’ [02F] |

| Unhealthy culture |

‘Oh! I just don’t like surgery … don’t like the culture, don’t like the politics, don’t like the hierarchy.’ [06F] |

| Absent seniors |

‘I think, things like general surgery, you never see anyone. You don’t see your registrars and you sure as hell don’t see a consultant … and so you just bumble through that one.’ [01F] |

| Uninterested supervisors |

‘I think the ones that never really engaged in any form of learning or interest in our progression, or even interest in learning our name … (laughing), I think that made it more difficult.’ [09F] |

| Unapproachable supervisors |

‘She was just unapproachable. She was quite cruel, very rude; just nothing that was useful as a supervisor.’ [07F] |

| Being put on the spot |

‘Having a boss that was maybe not very nice and she would kind of quiz me on the spot in a quite aggressive way that would make me feel really uncomfortable and sh***y and … yeah, I don’t feel like that helped at all with learning. It just made me stressed.’ [14F] |

| Judgemental seniors |

‘I know if I’m in an environment where I know people are being judgemental, I won’t ask a question because I fear that I’m going to look stupid.’ [02F] |

| Bullying by seniors |

‘He insinuated that I was bulimic … and called me a sl*t on top of some really other weird, creepy things that he would say and do … On my walk home, I would just be crying. And I was like, “I can’t do this anymore.”’ [02F] |

| Feeling scared to speak up |

‘If you just feel this big gap I think between you and them, you inherently feel a bit frightened to speak up, and you don’t want to let them down, you don’t want to look dumb and unfortunately I think that massively stands in the way of learning.’ [15F] |

| F, female; M, male |

Synthesis of results

Interns stated that they learned clinical and clerical skills as well as other skills necessary to work in the healthcare system. They believed that they learned from a variety of individuals in the workplace and by themselves in certain challenging situations. During most learning processes, interns built on their existing knowledge with help from an MKO and in an environment that was conducive to learning. The exceptions included instances where interns had to manage complex situations on their own with no previous experience or training. These situations arose when the MKO was absent. Learning is influenced by workplace factors (staffing, culture, workload and organisation), supervisor/senior doctor factors (presence, interest in teaching, attitude towards junior doctors) and learner factors (social and emotional wellbeing, and workload). Figure 1 represents how the findings of this study fit within the construct of Vygotsky’s theory.

Figure 1. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of learning during internship

Discussion

This study serves to build the evidence on how teaching and learning during internship can be improved. The findings show that interns learn most aspects of the set prevocational curriculum, such as clinical/administrative management, assessment and treatment of clinical conditions, skills and procedures, and communication. They learn from a variety of MKOs, who provide interns with a broader view of the healthcare system. Similar to those from other countries, Australian interns also learn through a master–apprentice-type relationship with their consultants or registrars.28 Interestingly, the literature on medical interns learning from other professionals such as nurses, pharmacists and allied health professionals is sparse and requires further research. In addition, the usefulness of organised teaching sessions, which are often sponsored by pharmaceutical companies, depended entirely on the quality of the presenter and the relevance of the topic.

The results of this study also reiterate the importance of the learning environment. When supervisors were supportive and encouraging of interns and showed interest in teaching, they were, in fact, teaching interns how to be compassionate professionals and trustworthy and helpful colleagues. On the other hand, when senior doctors were uninterested in teaching or were unapproachable, rude, judgemental or bullying, they were demonstrating that interns were not wanted and were unwelcome in the workplace. The same applied to organisational structure and culture. This is what Hafferty referred to as the informal and hidden curriculum10 and is similar to what Vygotsky believed to be the social environment and social interactions.

If learners internalise the knowledge, skills and culture of their MKOs, as proposed by Vygotsky, then they might also be persuaded to espouse how seniors behave professionally towards their patients and their subordinates. This internalising of unhealthy behaviours might contribute to continuing that culture in the workplace. The present findings concur with reports that certain specialities appear to be more affected by this hidden curriculum than others.29 Professional behaviour of clinical teachers is therefore inextricably linked to the learning environment and is known to influence career decisions of junior doctors. When seniors are inspiring and support them in their learning, junior doctors feel more inclined to take up their speciality.

Hospital consultants who supervise registrars and junior doctors rarely receive training in supervision.5 Neither is there any kind of accountability on the part of the supervisor to provide an optimal learning experience for junior doctors. The medical learning environment is an important field of scholarship, with an increasing number of authors reporting on the need for a more standardised approach, particularly since internship experiences of junior doctors can have a significant impact on their future careers and professional behavior.

Furthermore, there needs to be some way of enforcing standards for professional behaviour of medical professionals that does not jeopardise the learning and careers of junior doctors. Internship coordination agencies and faculties can develop and implement programs to teach and evaluate professionalism and, in so doing, enable the establishment of a safe and supportive learning environment for junior doctors.

Teaching in general practices has traditionally been well received.30,31 Students are mostly treated with respect, have the opportunity to work independently and have a broad clinical exposure.32 Previous research has also highlighted the untapped potential in the field of general practice teaching. For instance, involving general practice trainees as teachers increases primary care teaching capacity and promotes general practice as a potential career option. However, general practice trainees appear to have fewer opportunities to teach than their counterparts in other hospital-based specialties.33

This study had some limitations. There were far more female participants than male. This may have resulted in gender-biased responses. Nonetheless, it is important to recognise that there are more female medical students and female GPs than their male counterparts in Australia. Time constraints also curtailed further recruitment of participants. In addition, the study was conducted between one and four years after junior doctors had completed their internship, which could have resulted in some memory bias. However, direct and focused interview questions made it easier for participants to remember their foremost experiences related to learning during internship. This study highlights aspects of a crucial period of medical education and reiterates the importance of professional behaviour of senior doctors in learning during internship.

Conclusion

This study showed that interns learned most aspects of the prevocational curriculum set in the Australian Curriculum Framework for interns. It also showed that interns learned in different ways depending on the type of knowledge and skill from a variety of individuals in the clinical setting. The learning environment was typically influenced by the professional behaviour of clinical teachers and supervisors. A safe and supportive learning environment is necessary for optimal learning outcomes during internship. Professional behaviour standards towards interns for senior doctors and supervisors needs to be enforced to ensure a safe and supportive learning environment for interns and junior doctors.