Antibiotics are prescribed more often in primary care than other settings, with 42% of the Australian population being given at least one antibiotic prescription in 2017.1 Many of the conditions for which antibiotics are prescribed are self-limiting conditions, and antibiotics are often not needed, such as acute respiratory infections (ARIs) such as sore throat, acute bronchitis and acute otitis media (AOM).2–4 These conditions are highly prevalent in general practice, and antibiotics are overprescribed at rates 4–9 times as high as those recommended by Australian guidelines.5

General practitioners (GPs) are almost three times more likely to prescribe an antibiotic for their patients if they believe that the patients expect it.6 Perceived patient demand has been found to have a significant and independent effect on prescribing.7 There is often limited exploration and management of antibiotic expectations in consultations.8 Better managing patient expectations in consultations for acute infections may be important for reducing prescribing, particularly for self-limiting conditions.

Patients’ expectations of the need for antibiotics for common acute conditions

Some patients erroneously believe that antibiotics are needed to treat any type of infection9 and that antibiotics are needed to kill the bacteria that is causing the infection.10 A commonly held belief is that an infection will not get better unless it is treated with antibiotics – this belief has been identified in multiple studies of patients with ARIs10 as well as those with other acute conditions, such as acute infective conjunctivitis.11

The benefits of antibiotics for acute infections are generally overestimated. A survey of Australian parents found that most participants overestimated the benefits of antibiotics for reducing the duration of respiratory infections.10 For example, participants believed that antibiotics provide a mean reduction in the duration of acute cough by five days, sore throat by 2.6 days and AOM by three days. This contrasts with estimates, from systematic reviews, of a reduction in illness duration from antibiotics of approximately half a day.10

Patients’ expectations of or requests for antibiotics may reflect a desire for symptomatic treatment, lack of awareness of other options or previous experience of being provided with antibiotics. For example, in a study of patients with sore throat who asked for an antibiotic prescription, they were predominantly concerned about obtaining pain relief and believed that antibiotics were needed to relieve pain.12 Patients with conjunctivitis presented for antibiotic treatment because they were unaware of other potential options for managing the condition; they indicated that if they knew about the self-limiting nature of conjunctivitis, they would be willing to wait a few days before seeking medical advice.13 In women with lower urinary tract infection, their experience with current symptoms and/or previous experience with antibiotic treatment (either positive or negative) affects their request for an antibiotic or acceptance of a delayed antibiotic strategy.14 In a study of patients with a history of cellulitis, many were unaware of the risk of recurrence, expressed concerns about antibiotic side effects and were willing to accept a no-antibiotic prevention strategy.15

Poor awareness of the potential harms of antibiotics can also contribute to patients’ desire for them.10 Many people have misperceptions about the nature of antibiotic resistance – believing that it is the body, not the bacteria, that becomes resistant to antibiotics – and a poor understanding of the consequences of resistance.16–18

Beyond the media, the largest patient education workforce moulding patients’ expectations is GPs. But to do that well, more GPs need to be aware of their contribution to antibiotic resistance. Some clinicians do not perceive antibiotic resistance to be a problem, and of those who do, it is often perceived as not ‘their problem’.19 In a study of Australian GPs, few recognised antibiotic prescribing as a contributing factor to the problem of resistance, and it was generally believed that individual-level antibiotic prescribing does not contribute to the problem of resistance when compared with hospital prescribing or antibiotic use in agriculture.20

Strategies for dealing with patients’ antibiotic expectations and/or requests

Deny antibiotics

One strategy is to simply deny antibiotic prescription requests. However, there can be unwarranted problems associated with this. The GP–patient relationship is highly valued,21 and GPs are more willing to prescribe antibiotics if they feel that denying an antibiotic prescription will damage the relationship with their patient or lead to unnecessary confrontation.22 Some GPs believe that denying an antibiotic prescription may lead to their patient visiting another GP who is willing to prescribe it. Moreover, some GPs believe that denying antibiotics will not help to alter the patient’s beliefs or antibiotic expectations for the next consultation.22

One strategy that may help is for practices to make a public commitment to encouraging judicious antibiotic prescribing for acute infections. In practices randomised to displaying a poster-sized prescribing policy in the GPs’ waiting room and/or examination room, there was a 20% absolute reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rate relative to the control group.23 Clear and consistent messaging in the mass media and public health campaigns about antibiotics not being needed for many infections can also help to improve public knowledge and expectations about antibiotics. NPS MedicineWise periodically runs media campaigns to achieve this. Media and public health campaigns are discussed further in the article in this issue by Glasziou et al.24

Delayed prescribing

Delayed prescribing can be used as a strategy when antibiotics are unlikely to be needed but a prescription is provided as a precaution. Delayed prescribing has been successfully used in primary care to reduce antibiotic prescribing for respiratory25 and urinary infections26 and bacterial conjunctivitis,27 and it is a safe strategy for most patients, including higher risk subgroups.28 In a recent systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis from nine randomised controlled trials and four observational studies,28 complications resulting in hospitalisation or death were lower with delayed prescribing when compared with no antibiotics (odds ratio [OR]: 0.62; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.30, 1.27) or immediate antibiotics (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.53, 1.13). Patients who received a delayed prescription were more satisfied than those who received no antibiotics at the end of the consultation,25 and with a significant reduction in consultation rates (OR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.60, 0.87).28 Thus, delayed prescribing may be a preferable strategy to simply denying antibiotics, especially when consulting with challenging patients. Delayed prescribing and safety netting is discussed further in the article in this issue by Magin et al.29

Shared decision making

Shared decision making is a strategy that shows promise in reducing antibiotic prescribing. It is an approach to communication and collaborative decision making in which clinicians and patients jointly discuss the available treatment options (including the option of ‘no active treatment’ when that is appropriate), the potential benefits and harms of each option and the patient’s values, preferences and circumstances.

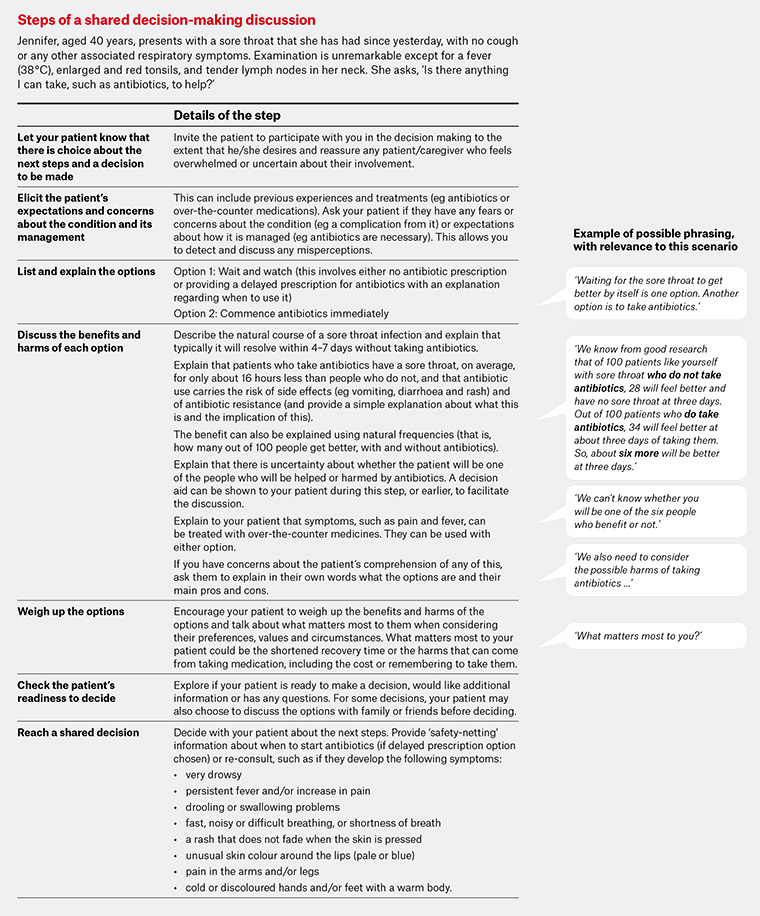

30 Figure 1 explains the typical steps in a shared decision-making conversation, using the scenario of deciding about antibiotic use for acute sore throat.

Figure 1. Steps in a shared decision-making discussion, with examples for the scenario of deciding about antibiotic use for acute sore throat. Click here to enlarge

In general practice, consultations for acute infections such as ARIs are particularly suited to shared decision making. This is because of misperceptions of the benefits and harms of antibiotics and the delicate balance between the marginal benefits of antibiotics and the possible individual and community harms from them. Shared decision making provides the opportunity to elicit and discuss expectations and correct any misperceptions about antibiotic benefits and harms and the infection. It enables GPs and patients to discuss the benefits and harms of using and not using antibiotics and jointly decide on the most appropriate option for that person at that time.

In a Cochrane review that examined the effect of interventions that facilitated shared decision making in primary care consultations with patients with ARIs,31 the interventions significantly reduced antibiotic prescribing at or immediately after the index consultation by 47%, compared with 29% in the usual care group (risk ratio 0.61; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.68; P <0.001). The reduction in antibiotic prescribing was not associated with an increase in re-consultation rates or decrease in patient satisfaction.31

Delayed prescribing can be used in conjunction with shared decision making for self-limiting conditions such as ARIs, uncomplicated urinary tract infections, conjunctivitis and skin infections such as non-bullous impetigo.25,27,32,33 If the option of ‘wait and see’/no immediate antibiotics is chosen, patients and GPs may sometimes feel more comfortable if an ‘in case’ antibiotic prescription is provided, along with safety-netting information about when to use it or re-consult. As shown in Figure 1, as part of this option, it is important that patients are told how long it would normally take for the infection to resolve if antibiotics are not used. Public campaigns such as Choosing Wisely Australia encourage patients to ask their clinicians ‘what happens if I do nothing?” as part of the decision-making process.

Shared decision making can be facilitated by using decision support tools such as patient decision aids. These tools provide evidence-based information about the health condition, treatment options (including the option of ‘wait and see’ when appropriate), the benefits and harms of each option and the likelihood or size of the benefits and harms. When aids are used in a consultation, higher levels of shared decision making and discussion of benefits and harms are observed.34 However, the use of aids does not guarantee that shared decision making will occur, nor are they essential for shared decision making to happen – it is the nature and content of the conversation that is important.30

Shared decision making can be more challenging, but is still possible, with people who have low health literacy. Systematic reviews35,36 have shown that the comprehension of health information among patients with low health literacy can be improved by reducing medical jargon, presenting essential information first, tailoring the amount and speed of information provided and using easy-to-read tools. These principles also apply when engaging patients with low health literacy in shared decision making.

Table 1 lists some of the tools that can be used in consultations for acute infections, including patient decision aids, guidance boxes, ARI action plans that list ways to manage symptoms, and patient education materials that can sometimes be used in conjunction with other resources or on their own (eg a discussion about a simple common cold is unlikely to require a shared decision making process).

| Table 1. Resources to assist with shared decision making and/or patient education for common acute infections |

| Indication |

Available resources (and where to locate them) |

| Patient decision aid |

NPS MedicineWise Respiratory tract infection action plan* |

Guidance (on shared decision making) box |

Patient education materials (printed or online) |

| Acute rhinosinusitis |

✓† |

✓ |

✓‡ |

✓§,‖,# |

| Acute otitis media |

✓** |

✓ |

✓‡ |

|

| Acute sore throat |

✓** |

✓ |

✓‡ |

✓§,‖,# |

| Acute bronchitis |

✓** |

✓ |

✓‡ |

✓§,‖,# |

| Uncomplicated urinary tract infections in non-pregnant women |

|

|

|

✓#,††,‡‡ |

| Acne |

✓§§ |

|

✓‖‖ |

✓# |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection |

|

✓ |

|

✓# |

*NPS MedicineWise – Respiratory tract infection action plan

†Therapeutic Guidelines – Patient decision aid, in Antibiotic: Ear, nose and throat infections (Acute rhinosinusitis)

‡Therapeutic Guidelines – Shared decision-making boxes, in Antibiotic: Ear, nose and throat infections

§NPS MedicineWise – Respiratory tract infections

‖NPS MedicineWise – What every parent should know about coughs, colds, earaches and sore throats

#NPS MedicineWise – Antibiotics, explained

**Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care – Decision support tools for consumers

††Royal College of General Practitioners (United Kingdom) – Urinary tract infection resource suite

‡‡NPS MedicineWise – Urinary tract infections (UTIs) explained

§§Windsor Clinical Research Inc – Acne decision aid

‖‖Therapeutic Guidelines – Information for patients with acne, in Dermatology: Acne |

Conclusion

Patients’ expectations of the need and requests for antibiotics for acute conditions are strong influencers of GPs’ prescribing behaviour. Simply denying antibiotics is one strategy; however, it can have unwanted effects on the GP–patient relationship and does not assist with modifying patients’ beliefs and expectations about antibiotics for future conditions. Shared decision making is an approach to communication that involves elicitation and discussion of patients’ antibiotic expectations, the benefits and harms of using and not using antibiotics, and alternative options. It involves patients and GPs reaching a collaborative decision about whether to use antibiotics, can also incorporate the strategy of delayed prescribing and may be an important way to reduce antibiotic prescribing.