In many countries, family medicine or general practice has been established and developed over decades, with high percentages of medical students becoming family doctors (or general practitioners) after graduation.1–4 In Vietnam, community or commune health centres (CHCs) and district hospitals are the most important facilities at the primary care level. However, most CHCs do not have a family doctor; 30% of CHCs do not even have a medical doctor.4 The lack of resources and limited medical facilities (eg restricted medication prescription list and the unavailability of blood testing) results in low quality at the primary care level and is the main reason why patients bypass community and district levels and go directly to provincial hospitals, although most of their illnesses can be diagnosed and treated at a lower level.

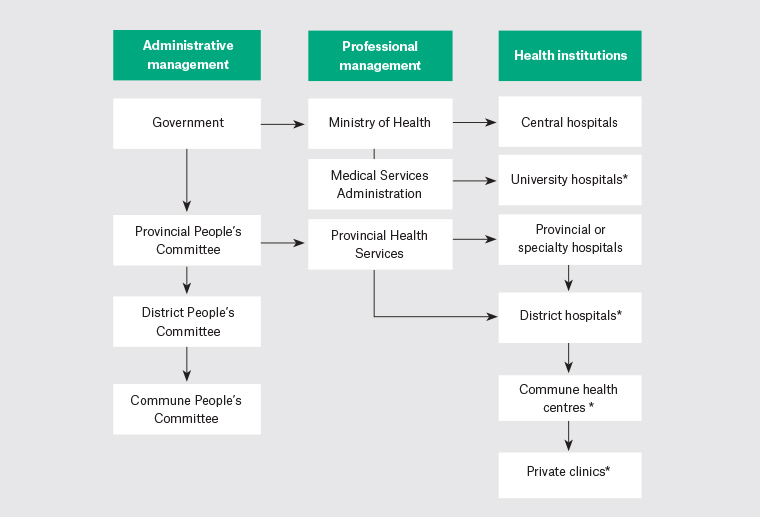

In 2013, a national plan for family medicine development was established to improve the quality of primary care (called Circular No 16). For the period 2016–20, the Ministry of Health approved the piloting of family medicine clinics in eight of 63 provinces/cities, expected to expand up to 80% of provinces/cities throughout the country by the year 2020.5 According to this policy and an updated Circular in 2019 (called Circular No 21, which replaced Circular No 16), family doctors can work in either a CHC, an out-patient department of a district hospital or a full-time or part-time private clinic. Each university medical centre has not only been a clinical practice site, but also one of the pilot family medicine clinics in the national strategy (Figure 1).6,7 Currently, training family doctors and family medicine module(s) for undergraduate students have become common in most medical universities. So far, visits to family doctors in some pilot clinics have increased, but family medicine–based care is not common and recognised by the community.

Figure 1. The Vietnamese healthcare system

*The different institutions that contain pilot family medicine clinics (following the Circular No 21/2019/TT-BYT of the Ministry of Health)

For many years, a main resource for CHCs and district hospitals has come from upgraded doctors. An upgraded doctor is a doctor who completes a four-year additional training program after completing a three-year assistant doctor program and has been clinically working for at least 12 months. The duration of the main medical training program is six years. Family medicine has been taught mainly in the two-year postgraduate programs (called specialist level one) since 2003 and in a three-month continuing medical educational program for licensed medical doctors since 2014. Since 2017–18, a two-week family medicine rotation has been integrated into the undergraduate six-year and four-year medical programs. A previous study showed that the family medicine rotation had an impact on students’ knowledge, attitude and skills towards family medicine.8 However, the lower status of family medicine in comparison to other specialties may lead to low levels of interest in this discipline by students and medical staff.

At present, determining how to attract medical students to work in primary care is a common question in many countries.9–12 Research in several countries has shown that interest in and career choice toward family medicine or primary care depend on many factors: medical student aspiration for high status specialties, the representation of the profession, presence of training in this discipline in undergraduate programs as well as training duration.13–17 Senf et al reviewed 36 articles on family medicine specialty choice that were published between 1993 and 2003. Students who believe primary care is important, have a rural background, have low(er) income expectations, have career intentions at entry to medical school and do not plan a research career are more likely to choose family medicine. The time dedicated to family medicine in clinical years is related to higher numbers of students selecting family medicine. Faculty role models have both positive and negative influences.18

To these authors’ knowledge, no study has been conducted into how students perceive family medicine and their potential career choice in the context of a new family medicine module introduced into undergraduate training and the national supportive campaign in developing countries such as Vietnam. The objective of this study was to explore how sixth-year medical students perceive family medicine after having completed an experience-based module on family medicine, and to explore which factors influence their choice for a career in family medicine.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative research study with in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. Thematic analysis was used.19–21

Participants

The study was carried out among sixth-year medical students who had completed the fifth-year family medicine rotation the first time it was offered at Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam. The sample included eight in-depth interviews (DIs) and four focus group discussions (FGDs) with 36 students. A criterion sampling technique was used to recruit a heterogeneous group of medical students from different class groups; students in one FGD all belonged to the same class. Participants were recruited with the help of class monitor students who identified students who showed interests in the research topics and could give rich information. The sample had an equal distribution in students’ sexes and origins (rural/urban area). No participant refused to join the study. More DIs and FGDs had been planned in the event the information was not saturated, but this proved unnecessary.22–24

Research team

The research team consisted of experienced researchers in education, quality research, family medicine and community health. The facilitators of the FGDs and DIs were teachers in public health and family medicine.

Data collection

Data collection period

Data collection was carried out from January to March 2019. This period was the students’ twelfth (final) semester. The students had completed a family medicine rotation in their tenth semester and other courses in most specialties and subspecialties after that. They were interviewed six months before they graduated to become medical doctors.

Data collection methods

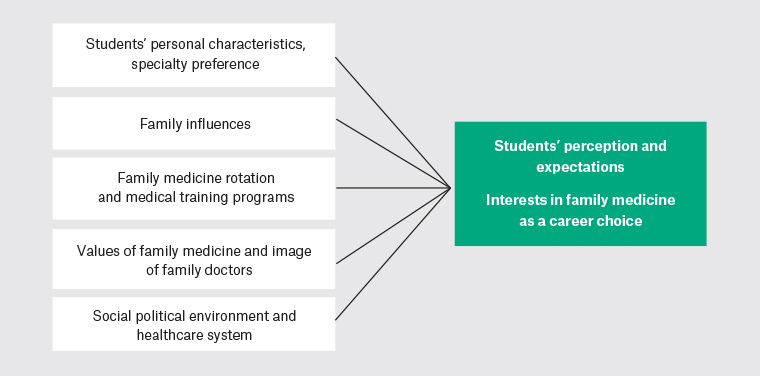

A conceptual framework was built to explore the possible influencing factors on students’ interests (Figure 2) on the basis of a literature review and the experience of the research team. From that, a question guide for DIs and FGDs was developed. To ensure that the question guide was valid, a pilot study was done with a DI and an FGD with eight students in November 2018. After being piloted, the order and further exploration of different parts of the question guide were adapted (Box 1).

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of students’ perceptions of and interests in family medicine and some possible influencing factors

| Box 1. Question guide for in-depth interviews and focus group discussions |

1. Self-introduction

Tell me about yourself: Where are you from (name of province, rural/urban area)? Which rotation are you now taking?

2. Perceptions towards family medicine

You studied family medicine a year ago. What do you understand about this discipline? (Describe in detail, in your own words, the work or practice of family doctors, and their roles in the health system.)

3. Interests in family medicine, at a certain model/practice place

Because there are three different models of family medicine (commune health centre, district hospital, private clinic full time/part time), please tell me in detail about your interests in each model.

Please explain more about this.

4. Career choice in family medicine, and at a certain model/practice place

How likely is it that you will choose family medicine for your career?

Please explain more about this.

5. Factors influencing your career choice in family medicine

Which factors are important for your choice of specialty? Please explain in detail.

Example: Is the place where you’ll live important?

Other factors to be considered: work–life balance, income, university, training programs, health policy, other? |

The DIs and FGDs took place in comfortable meeting rooms or offices in the university but outside the family medicine department. Both types of interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. All DIs and FGDs were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim to facilitate subsequent data analysis. The rules for FGDs were verbally introduced to participants to engage them and allow them to feel comfortable in the discussions. One of the two interviewers facilitated the discussions or interviews while the other acted as an observer (to gain more non-verbal information) and secretary (to take field notes of the interview). Before the discussions, the first author – who was also a family medicine teacher – introduced the study objectives to the participants, but she was not present during the meetings.

Data analysis

The authors used line-by-line coding of each case’s interview responses, followed by a comparative thematic analysis of all cases. The researcher and the two interviewers independently coded each interview, and all codes were entered manually into an Excel matrix. Next, the authors met as a team several times to discuss the codes and identify emergent themes until a concept map that represented the study’s findings could be developed. The DIs/FGDs were conducted in Vietnamese and then analysed in the native language to completely understand what was meant in the appropriate context. After that, English translation of the main findings was performed to allow discussion with the non-Vietnamese co-authors.

The group of native language–speaking analysers discussed any disagreements about emergent categories to make sure that the participants’ points of view were captured. This process of cross-checking coding of the major categories provided ‘thoroughness for interrogating the data’ and helped while analysing the interview data.

Ethical issues

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy (HE20180012). The study participants were well informed about the study and gave their oral consent to being interviewed. Their anonymity was protected and guaranteed by the researchers. The participants had finished their clinical rotations in family medicine department, so their responses would not influence their study scores or examinations.

Results

Participants

There were 36 students participating in this study. Eight students were interviewed with DIs and 28 students participated in four FGDs (an average of seven students per FGD). Sex was equally distributed in both DIs and FGDs.

Perceptions about the roles of family doctors and benefits of family medicine for healthcare

Most students were able to describe what they learnt about the roles of family doctors. They understood that family doctors were doctors who provided care that was continuing, comprehensive, preventive and family focused. Particularly, they appreciated that one of the important roles of family doctors was the management of common chronic diseases.

I think that family doctors have an advantage that they see all members in the same family and follow up them in a long term. In addition, family medicine can be at community, district or central [provincial] levels. Family doctors can perform screening, first contact, often manage common diseases, chronic illnesses, long-term diseases, inherited diseases and screening for families. [Female student (FS), DI-1]

All students recognised the benefits of family medicine as ‘reducing healthcare cost for both patients and the healthcare system, reducing hospital overload and mortality rate. Family doctors were able to help many people, and so family medicine could improve the capacity of health staff as well as improve patients’ trust on health staff at lower levels of care’ [FS, FGD-1].

Most students agreed that family doctors could work at most levels of the healthcare system. They recognised that there is a big demand for this kind of doctor at primary care level including CHCs, district hospitals, private clinics and even provincial hospitals.

Interests and career choice in family medicine

Most students showed little interest in family medicine. They saw advantages and disadvantages for each of the different practices: community health centres (out-patient departments) of district hospitals, provincial hospitals and private clinics (Table 1). In general, the participants showed equal interest in all levels of healthcare, but more participants preferred working at the provincial hospitals because of several advantages.

| Table 1. Participants’ perceptions about family practice at different sites |

| 1. Commune health centre (CHC) |

Advantages

- Close to families; less travel and lower cost for families

- Better understanding and close relationships between doctors and patients

Disadvantages

- A low level of trust, resulting in fewer patients coming to CHCs

- Lack of equipment, laboratory tests and medication

- Few chances for being trained, and probably low income

- Others: doctors were responsible for many preventive programs; time-consuming paperwork, including for health insurance reimbursement

|

| 2. District hospital |

Advantages

- Probably higher levels of patient trust in doctors, greater numbers of patients, availability of subclinical tests supportive for diagnosis and treatment, and higher income when compared with CHCs

- Fewer challenges than CHCs and provincial hospitals

Disadvantages

- Fewer patients and fewer challenges, which may make it less appealing than upper levels of care

|

| 3. University medical centre (equivalent to provincial hospital) |

Advantages

- Enough equipment, subclinical tests and medications

- Various specialties that could be supportive for patients

- Chance to see a broad spectrum of patients

- Provincial hospitals are the main practice sites in the medical curriculum, so they become most familiar to students

Disadvantages

- Less time for patients because of overcrowding, and less continuing care

- Unclear spectrum of patients in primary and secondary care because specialists took the roles of family doctors in many cases

|

| 4. Private clinics |

Advantages

- Higher level of trust in doctors (and consequently high adherence) and active involvement of patients in the healthcare process

- Flexible time for both doctors and patients (out of working hours)

Disadvantages

- Continuing care was sometimes not applicable, and cost could be higher

|

I think all levels [health institutions] need family doctors, because patients come to see doctors everywhere. Personally, it is most convenient at provincial hospitals because they concentrate many patients and there are more facilities for diagnosis and treatment. [Male student (MS), FGD-2]

However, they were confused about choosing family medicine as a career. Among those who were interested in the discipline, four interviewees expressed a career choice for family medicine; another four participants emphasised that they would consider family medicine as a career choice when the disadvantages were solved.

Factors influencing a career choice for family medicine

Those students who expressed their interests in a career in family medicine highly valued the relationships between doctors and patients, continuing care and either a good work–life balance or challenges to overcome (Table 2). Students’ families sometimes have a role in orienting, but not imposing on, students’ career choices. The family medicine rotation had a very high impact on students, as they could observe and participate in the clinical practice of family doctors.

| Table 2. Influencing factors to students’ family medicine career choice |

| Students’ characteristics |

– |

Gender and hometown: These were not considered as influencing factors. |

| – |

Recruitment: Students who were sent for medical training by their provincial health departments need the health authorities’ approval for their choices. |

| – |

Existing career choice: Many participants had career choices for specialties in which they would have a longer supervised training program and a clear development pathway. |

| – |

Income: Some students estimated lower income of family doctors than specialists; some others thought income could be the same among doctors. |

| ++ |

Life balance: Family doctors might have better life balance with more patients to see, but not many cases requiring intensive care. |

| Students’ families |

– |

The students’ families had an impact but did not impose on students’ choices. Students were influenced by family members who were healthcare workers. |

| Family medicine rotation and medical training programs |

++

|

Family medicine rotation: This was very important to students, influenced by the following factors.

- Their interests were from the clinical rotation including attending theoretical classes, observing daily work of family doctors and participating in clinical practice

- Enthusiasm of lecturers, interesting clinical case studies and challenging examinations that enhanced their learning motivation

- Satisfaction of patients seen by family doctors

|

| + |

The rotations have just been taught for two years, and their two-week duration was short. |

+

|

Other reasons: There were many chances for postgraduate studies abroad and potential development in the future similar to developed countries. |

| + |

The parallel program to train upgraded fourth-year doctors: It was not considered an influencing factor by the sixth-year students |

| – |

Not strong coverage of primary care in the curriculum; not positive attitude of the university toward primary care |

| Value of specialty and images of family doctors |

++

|

Values of specialty: Family medicine improves primary care and continuing care; enhances the relationships between doctors and patients. |

| + |

Images of family doctors: A few students thought family doctors should know a lot of domains/specialties, so doctors had to be smart or hard-working; consequently, family medicine was viewed as a speciality that was too broad or too difficult by students who preferred a narrow specialty that focuses on specific diseases. In addition, a few students thought it was not a specialty that often focused on specific diseases. |

| Sociopolitical environment and health system |

–– |

Health policies: They were considered to have a big impact on students’ choices.

- It lacked a clear pathway of professional practice, including a good network for family medicine practice, regulations for first contact, supportive referral system, electronic health record

- Perceptions of patients and health professionals were still low

- A clear pathway of professional development was also vital to career decision

|

++: positively influencing and important to students

+: positively influencing but not important

–: negatively influencing but not important

––: negatively influencing and important |

I liked to practise in the out-patient department where I could see patients’ satisfaction with a family medicine teacher. Some cases got more exact diagnoses because she spent more time on history taking. I was also interested in learning clinical cases about common problems. [FS, DI-2]

Participants saw the current sociopolitical environment mainly as a disadvantage and one of the reasons for not choosing a career in family medicine.

I don’t know much about income, but think it could be the same as that of doctors in public hospitals. The main reasons for not choosing family medicine career are that family medicine [primary? care system] has still not been developed and not common. Patients do not know what family doctors stand for, so that limits their visits. [MS, FGD-3]

I am afraid of becoming a family doctor because it requires broad knowledge, with little support at the CHCs. [MS, FGD-3]

I will get bored if I work at a CHC. I will just treat simple diseases and usually refer to specialists. [MS, FGD-4]

Suggestions from the participants

For the undergraduate curriculum

The students suggested maintaining clinical teaching methods in the family medicine rotation, increasing opportunities for clinical practice and keeping the module attractive with various case studies, multiple-choice question tests in the context of out-patient settings and family practice. They liked to receive more information about family medicine training from the university and department.

Family medicine rotation should be increased because its duration [two weeks] is too short for students to have many opportunities for practice. It contributes to the reason why students do not choose this specialty for their profession. [FS, FGD-2]

The reason for not choosing family medicine as a career is that students do not know much about it while they are in much contact with the four specialties internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and pediatrics. They often think about these specialties first. This specialty is quite new which makes it attractive for doctors who want to ‘become the first’ or ‘make a difference’. [MS, FGD-3]

For the health authorities

Healthcare policy has a big impact on students’ choices. A good system for family medicine practice is essential for regulations such as first contact, a supportive referral system, electronic health records, raised perceptions of patients and health professionals, and a clear pathway of professional development, which are all vital for students to choose a career in family medicine.

I recognise the discipline is very great but I will personally not choose it as my career. When there is a change, I will think again. But it might take much time because there are so many difficulties now. For example, the CHCs where I practised, was still very inadequate. I feel that newly graduated general doctors working at community level should be cautious because they are still too young, with too little experience. They need a good practice site to gain more experience and support; otherwise they will forget much knowledge learnt from university … I fear to work at CHCs and district hospitals. [FS, DI-1]

The low perception of people is one of the reasons [for not following family medicine as a career] … Even very good family doctors cannot perform well without good resources such as equipment, staff, and medication. Currently, most health institutions still follow ‘the old pattern’: there is a big need for innovation. [MS, DI-3]

Discussion

Most students in the present study did understand and could describe well what they had learnt about family doctors, and about the benefits of (potential) pilot family medicine clinics at each of the four different levels of care. Factors influencing the students’ family medicine career choice were recognising the values of family medicine, particularly the person-centeredness and the long-term doctor–patient relationship; the value of the family medicine rotation and family medicine teachers’ positive roles in it; and preferring a good work–life balance. This finding has been found in several studies elsewhere.2,3,11,16,25–27 In a systematic review, two similar and common factors in most countries were mentors as role models in family medicine, and the flexibility in working conditions.28

However, in the present study, the number of participants who showed a career preference for family medicine was low. As in many other countries, medical students prefer to become hospital-related specialists because this offers clear career development pathways, receives more support or is less strenuous due to a smaller spectrum of clinical problems to deal with.11,16,29–31 In addition, the two most important principles of family medicine (continuing and comprehensive care) have not been applied commonly, even at pilot clinics in Vietnam. Therefore, family doctors might be recognised as preventive doctors or generalists. There should be conditions that are conducive to providing long-term care as ‘real family doctors’, including patient allocation for family doctors. The Vietnamese situation might reflect the earlier stages of family medicine development in some developed countries.11 The values of family medicine were well known by students in theory, but not clear to them in practice. Students might be confused about what family doctors are well known for to attract their patients. This was also found in research in several middle- and low-income countries where the health system still had an emphasis on specialised medicine.28

Many studies on career preferences of graduating medical students that have been carried out over the past 10 years have been in regions where family medicine, unlike in Vietnam, has long been established (eg Europe, USA, Australia). Even those regions struggle to attract sufficient numbers of graduates to family medicine, and sometimes even witness a decline.16,28,32,33 In Vietnam, it would be hard to improve primary care quality without support and motivation from the health system for family doctors; students expect a clearer definition of healthcare services to be provided by family doctors, and about family doctors’ career pathway development.

The family medicine rotation that has been implemented in the fifth year of medical education in all Vietnamese universities is only a first, small step in increasing the presence of family medicine in undergraduate medical education. Other forms used in other countries are a preclinical family medicine elective, a four-week family medicine clerkship and a four-month family medicine rotation during the final year.2,9 Other strategies to enlarge the proportion of medical students choosing a career in family medicine are institutional reforms emphasising family medicine training and an increase in the size of the faculty.2,12,28,32

To these authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to examine family medicine perceptions by undergraduate students in Vietnam. The strengths of the study were that it was a well-designed qualitative study, with reliable and valid data collection and analysis. A limitation of the study is that it was done at only one medical university. Although a similar perception may be expected elsewhere, the two credits of family medicine imposed on all medical faculties might not be offered everywhere in the same way as at Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy.

The study explored the students’ views to identify barriers to improving family medicine and primary care. Two gaps for improvement were identified. The family medicine rotation should be maintained and become more prominent in more components of the medical curriculum; and health policies to support and encourage becoming a family doctor are necessary. Further exploration of the impact of system approaches to family medicine is recommended.