Case

A man aged 62 years presented with a persistent, severely pruritic eruption that had progressed over the preceding five days. It initially affected his neck but later became generalised, involving his upper and lower back, forearms and thighs. His medical history was unremarkable, and he took no regular medications. He had no other symptoms and examination was otherwise normal. There was no mucosal involvement, and he had not had any previous similar episodes. Three days prior to the onset of the eruption, he had consumed an omelette containing partially cooked Lentinula edodes (shiitake mushrooms).

Question 1

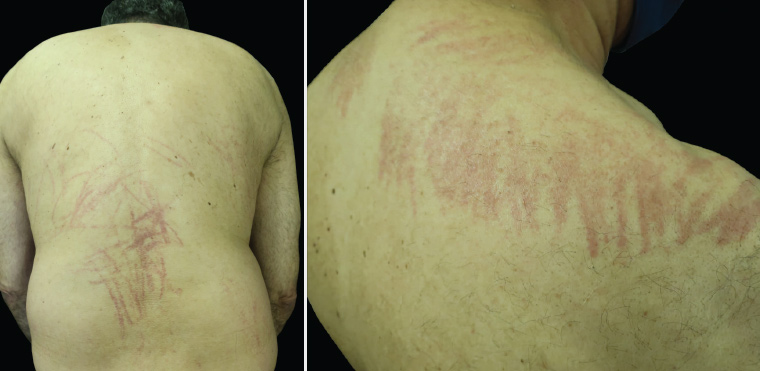

How would you describe the rash shown in Figure 1?

Figure 1. New-onset pruritic eruption affecting the back and shoulders

Question 2

What is your differential diagnosis?

Question 3

What is the cause of the patient’s symptoms, and what is the underlying pathophysiology?

Question 4

What causes the distinctive linear pattern of the rash seen in this condition?

Question 5

What is the typical distribution of the rash seen in this condition?

Question 6

What investigations should be performed?

Question 7

What is the natural history of this condition, and what treatment would you recommend?

Answer 1

The rash depicted in Figure 1 is a flagellate or ‘whip-like’ erythematous eruption.

Answer 2

The differential diagnosis in this case includes:1

- shiitake mushroom dermatitis

- dermographism

- phytophotodermatitis

- flagellate erythema secondary to medications (bleomycin, docetaxel, trastuzumab)

- flagellate erythema secondary to autoimmune diseases (dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still’s disease).

Dermographism (literally ‘write on skin’) refers to an increased tendency to develop urticarial welts in response to firmly stroking or scratching the skin. It is unlikely to be the diagnosis in this case, as the weals of dermographism fade within 15–30 minutes.

Phytophotodermatitis can produce a linear rash and is caused by exposure to certain plants in combination with exposure to sunlight (specifically ultraviolet A). Lesions of phytophotodermatitis occur in sun-exposed areas, making it an unlikely diagnosis in this case.

Flagellate erythema secondary to medications or autoimmune disease is exceedingly rare.

Answer 3

Given the recent consumption of partially cooked shiitake mushrooms, the most likely diagnosis is shiitake mushroom dermatitis. In genetically susceptible individuals, shiitake dermatitis is thought to be caused by an immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to lentinan, a protein found within the cell wall of the mushroom.2–4 In almost all cases it is due to consumption of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms; however, cases involving dried or powdered mushrooms have been reported.2 Onset of a pruritic flagellate eruption occurs anywhere from two hours to five days after consumption.2 Systemic manifestations including fever, diarrhoea and malaise rarely occur.2

Answer 4

The linear pattern is thought to arise as a result of trauma caused by scratching (ie the Koebner phenomenon).5 It has been postulated that scratching causes increased deposition of lentinan within the skin, resulting in a localised inflammatory reaction at these sites.5

Answer 5

There is a predilection for the trunk and proximal limbs, which are affected in most cases.2 The face, neck and extremities are relatively spared.

Answer 6

The diagnosis can be made clinically on the basis of a flagellate eruption coupled with a history of recent consumption of shiitake mushrooms.2 Biopsy and laboratory investigations are not usually required. Biopsy findings are nonspecific and include spongiosis, dermal oedema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional eosinophils.2

Laboratory investigations are usually normal. Full blood examination occasionally demonstrates eosinophilia or neutrophilia. C-reactive protein, serum immunoglobulin E and lactate dehydrogenase are rarely elevated.2

Answer 7

Shiitake mushroom dermatitis is self-limiting with no known long-term sequelae. No treatment is required in most cases, with an average time to spontaneous resolution of approximately 10 days (range 2–35 days).2 In severe cases, supportive treatment with antihistamines and corticosteroids (topical or oral) can be used.2

Case continued

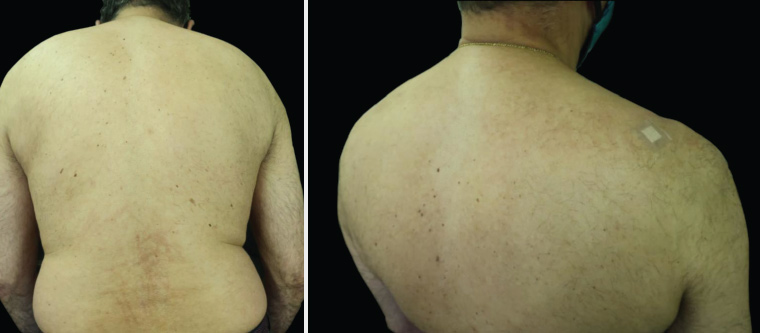

As a result of severe pruritus, the patient was treated with prednisolone 37.5 mg daily, cetirizine 10 mg three times per day and topical betamethasone 0.05% daily. After five days of treatment, there was almost complete resolution of his symptoms (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Photographs obtained post treatment demonstrating near-complete resolution. The dressing on the upper right shoulder is the biopsy site.

Question 8

What dietary advice should be provided?

Answer 8

Consumption of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms should be avoided, as symptoms will reliably recur.2,5 Shiitake mushrooms cooked above 150 °C for 15 minutes can be safely consumed in future, as lentinan denatures at this temperature.3,5 Shiitake mushroom dermatitis was first documented in Japan and China, where this mushroom is widely consumed, and cases have since been reported in the Americas, Europe and other Asian countries. Increased consumption of shiitake mushrooms globally is likely to result in a greater incidence of this distinctive flagellate dermatitis.

Key points

- Shiitake mushroom dermatitis is most often due to consumption of raw or partially cooked shiitake mushrooms.

- Patients presenting with a flagellate erythematous eruption should be asked about consumption of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.

- Treatment of shiitake mushroom dermatitis is expectant; corticosteroids (topical or oral) and antihistamines can be used in severe cases.