Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) affects approximately four-fifths of pregnant women.1 Severe nausea and vomiting is a common indication for hospitalisation among pregnant women during their first and second trimesters, leading to an average of five days of hospital admission.2–4 Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) can cause weight loss and volume depletion as well as ketonuria and ketonemia due to the intractable vomiting with starvation during pregnancy.5,6 Micronutrient deficiency and, rarely, Wernicke’s encephalopathy may occur. HG can adversely affect the quality of life of pregnant women.7

Numerous practice guidelines have been published detailing the treatment plans for HG. In this systematic review, international and national clinical guidelines that detail the guiding principles of treatment or management of adult patients with HG are evaluated. The objective of this review is to analyse the quality of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for HG by applying the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) protocol.8 General practitioners are the gatekeepers as they are often consulted for NVP. Quality of evidence-based CPGs is associated with the safe use of medication and optimisation of care quality of patients with NVP and HG. Nana et al has highlighted the importance of evidence-based medicine in the management of HG in primary care.9

Methods

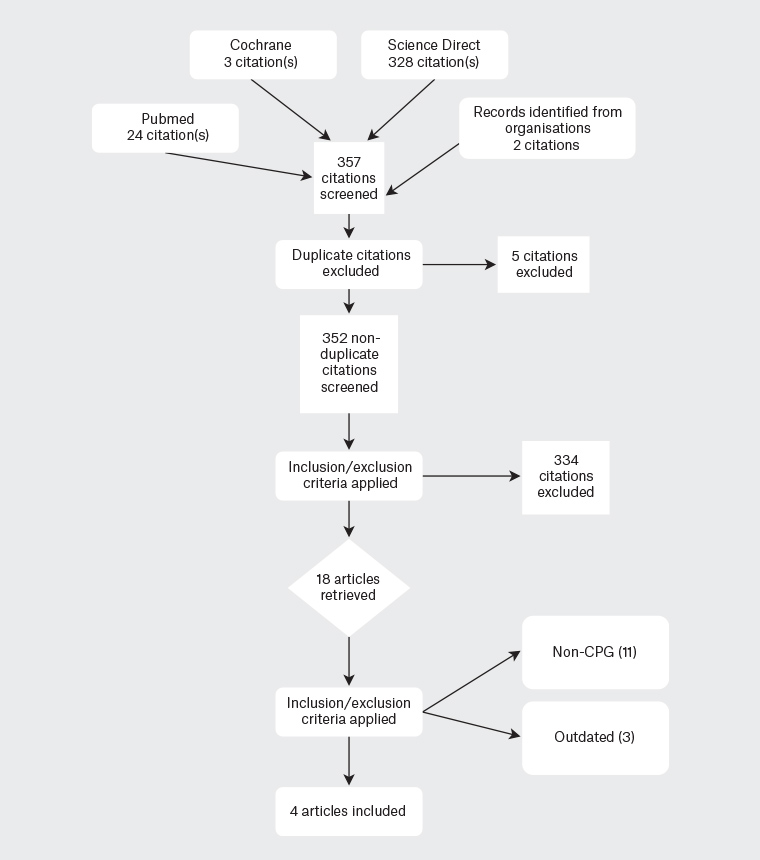

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines were followed. This study was registered with PROSPERO, which is an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021278910). International and national recommendations for treatment or management of pregnant women with HG were independently searched by all five authors. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were decided following discussion with all five authors. The authors searched PubMed, Cochrane and ScienceDirect databases from inception until 18 May 2021. Search strategies and results are shown in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1). The authors used the following MeSH terms: ‘Hyperemesis Gravidarum’ OR ‘Morning Sickness’ AND ‘Practice Guideline’ AND ‘Pregnancy’. The authors manually searched for national and international institutions and organisations, as well as evaluated references to major articles on this issue. In circumstances where more than one guideline or update was available, the most recent version of the guidelines was selected for this review. Two authors (ZYW, WXS) retrieved and examined the full-text articles. Consensus of all authors was used to make the final decision in the selection of the guidelines. Any conflict raised was resolved after discussion with all authors.

Figure 1. Study design by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‑Analyses (PRISMA 2020)

CPG, clinical practice guideline

Inclusion criteria were: 1) CPGs must include recommendations and assessment made by a panel of multidisciplinary experts on current evidence using a systematic review approach while comparing the advantages and disadvantages of alternative care approaches, 2) CPGs are required to be related to the treatment of HG, and 3) CPGs must be available in English.

The AGREE II tool was used as it is a well-recognised tool for quality assessment for CPGs. It comprises 23 items, each graded on a seven-point scale, with gradings (0–3: unacceptable, 4: neutral, 5–7: satisfactory). The items are grouped into six domains: 1) scope and purpose, 2) stakeholder involvement, 3) rigour of development, 4) clarity of presentation, 5) applicability, and 6) editorial independence. The guidelines in English included in the reference list were appraised independently by two authors (ZYW and KQO).

The sum of scores for each domain was calculated and converted to a standardised percentage. A consensus meeting was held to discuss differences of more than three points on each item on the original seven-point scale, in line with prior research.10,11 Cut-off scores to distinguish between high- and low-quality guidelines were not provided by AGREE II consortium. In the present study, domain scores of 50% or more were deemed high quality. In line with other studies,10,11 a domain score of more than 50% was deemed high quality, and the means of all six domains were calculated to categorise the overall quality of CPGs into 1) recommended (>60%), 2) recommended with modifications (60–30%) and 3) not recommended (<30%). The overall concordance and significance were determined using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. A kappa value of 0.00 implies poor agreement, 0.00–0.20 shows little agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicates reasonable agreement, 0.41–0.60 indicates moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 indicates significant agreement and 0.81–1.00 indicates near perfect agreement.

The quality of evidence and recommendations included in each CPG were reviewed and assessed. In the practice guidelines evaluated, various approaches and classifications were used (Table 1). A summary table regarding level of evidence and grading of recommendations was designed to guide practitioners on the basis of the consensus of the authors (Table 2).

| Table 1. Guidelines characteristics |

| Year |

Country |

Organisation |

Title |

Evidence-based grading system |

Evidence-based grading taskforce |

| 2019 |

Australia |

Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) |

Guideline for the management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum |

Studies: I–IV

Recommendation: evidence-based recommendations (EBR), consensus-based recommendations (CBR), clinical practice points (CPP) |

National Health and Medical Research Council |

| 2016 |

Canada |

Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) |

The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy |

Studies: I, II-1, II-2, III-3, III

Recommendation: A–E, I |

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care |

| 2016 |

UK |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) |

The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum |

Studies: 1++, 1+, 1-, 2++, 2+, 2-, 3, 4

Recommendation: A–D |

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) |

| 2018 |

USA |

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) |

ACOG practice bulletin 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy |

Studies: I, II-1, II-2, III-3, III

Recommendation: A–C |

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) |

| Table 2. Summary of evidence and recommendations |

| |

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) |

Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) |

Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) |

| Level of evidence |

| Strong |

I |

1++, 1+, 1- |

I, II-1 |

Level of evidence (LOE)-I–II |

| Moderate |

II-1, II-2, II-3 |

2++, 2+, 2- |

II-2, III-3 |

LOE-III |

| Weak |

III |

3, 4 |

III |

LOE-IV |

| Grade of recommendations |

| Strongly recommended |

A |

A |

A, B |

Evidence based |

| Recommended |

B |

B, C |

C, D, E |

Consensus recommendations |

| Recommended with discretion |

C |

D |

I |

Clinical practice points |

Results

The literature search identified four CPGs; as per the inclusion criteria, all four guidelines are in English. The years of publication are between 2016 and 2019. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the guidelines included. All four CPGs were developed and published by professional societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),5 the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC),12 the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in the UK13 and the Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ).14

Overall

Table 3 displays the total score for each domain and the overall quality of the guidelines. No guideline was deemed as ‘not recommended’. The RCOG (UK) guideline13 achieved the overall highest score (83.3%), while the SOMANZ guideline14 scored lowest (58.3%). Only the RCOG13 guideline achieved scores greater than 80% in all domains, making it the preferred CPG by the appraisers. The other three CPGs scored between 50% and 80% and were categorised as ‘recommended with modifications’. The weighted overall interrater agreement revealed a reasonable agreement (0.328).

| Table 3. Scores in each domain using AGREE II tool |

| Guideline |

Scope and purpose |

Stakeholder involvement |

Rigour of development |

Clarity of presentation |

Applicability |

Editorial independence |

Guideline overall score |

Recommendation |

| ACOG |

80.6%

35 (6–42) |

27.8%

16 (6–42) |

77.1%

90 (16–112) |

80.6%

35 (6–42) |

35.4%

25 (8–56) |

20.8%

9 (4–28) |

66.7% |

YwM |

| RCOG |

83.3%

36 (6–42) |

72.2%

32 (6–42) |

91.7%

104 (16–112) |

91.7%

39 (6–42) |

50.0%

32 (8–56) |

66.7%

20 (4–28) |

83.3% |

Y |

| SOMANZ |

66.7%

30 (6–42) |

41.7%

21 (6–42) |

51%

65 (16–112) |

63.9%

29 (6–42) |

56.3%

35 (8–56) |

54.2%

17 (4–28) |

58.3% |

YwM |

| SOGC |

77.8%

34 (6–42) |

47.2%

23 (6–42) |

74.9

87 (16–112) |

88.9%

38 (6–42) |

45.9%

30 (8–56) |

29.2%

11 (4–28) |

66.7% |

YwM |

| Mean domain score |

77.1% |

47.2% |

73.7% |

81.3% |

46.9% |

42.7% |

68.8% |

|

Obtained score by percentage (minimum possible score – maximum possible score). Domain scores were calculated by the following formula: (obtained score – minimum possible score)/(maximum possible score – minimum possible score). The maximum possible score was: number of items in domain × number of appraisers. The minimum possible score was: number of items in domain × number of appraisers.

Overall quality scores and inter-reader variability (Fleiss’ kappa) are commendable.

ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; SOGC, Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada; SOMANZ, Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand; Y, yes; YwM, yes with modifications |

Scope and purpose

On average, the CPGs were able to score 77.1% (range 66.7–83.3%) in this domain. The RCOG13 guideline achieved the highest score (83.3%).

Stakeholder involvement

A huge disparity was observed among the guidelines in this domain as the mean score was 47.2% (range 27.8–72.2%). The guidelines that scored below 50% were ACOG,5 SOGC12 and SOMANZ.14 The only exception was the RCOG13 guideline, at 72.2%. The RCOG13 presents a clear description regarding the multidisciplinary target audience across different healthcare settings.

Rigour of development

The steps of formulating and updating recommendations by gathering and synthesising evidence were examined under this domain. Overall, all guidelines performed well in the ‘rigour of development’ domain, with a mean score of 73.7% (range 51.0–91.7%). Level of evidence and grade of recommendation were used by all guidelines involved. RCOG,11 ACOG5 and SOGC12 were able to score more than 70% as they applied systematic methods in searching for evidence.

Clarity of presentation

This domain achieved the highest overall score. The mean score was 81.3% (range 63.9–91.7%) The SOGC12 guideline had the highest score, while the SOMANZ14 guideline had the lowest score among all four guidelines. Most guidelines made it easy to identify the recommendations, which is critical for clinical relevance and implementation in everyday practice.

Applicability

The mean score of the domains was 46.9% (range 35.4–56.3%). The RCOG13 and SOMANZ14 guidelines were able to score 50% or more in this domain. ACOG5 and SOGC8 guidelines were noted to lack information regarding ‘facilitators to implement recommendations and resource utilization’.

Editorial independence

This was the lowest scoring domain (42.7%, range 20.8–66.7%). Only RCOG13 and SOMANZ14 guidelines were considered high quality in this domain.

Recommendations

Table 4 summarises the four guidelines’ recommendations on the basis of evidence level and recommendation grade. There are some differences in the management of acute/mild-to-moderate NVP or HG. While ACOG recommends pyridoxine alone as a first-line therapy,5 RCOG does not.12 Although acid suppression therapy is commonly used in moderate-to-severe NVP, its efficacy requires further study. The most effective complementary therapy for NVP that is recommended by all four CPGs is ginger, and followed by acupressure and acupuncture supported by SOMANZ,14 RCOG11 and SOGC.12

| Table 4. Summary of level of evidence and grade of recommendations |

| |

|

SOMANZ |

RCOG |

SOGC |

ACOG |

| Acute/mild-to-moderate NVP or HG |

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) alone as first‑line therapy |

– |

– |

Level I, Grade A |

Level A |

| Combination of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) plus doxylamine as first-line therapy |

– |

– |

Level I, Grade A |

Level A |

| Pyridoxine is not recommended for NVP or HG |

– |

Level 2++, Grade C |

– |

– |

| Oral antihistamines (H1 receptor antagonists) as first-line antiemetics |

– |

Level 2++, Grade C |

Level I, Grade A |

– |

| Moderate-severe NVP |

Dopamine antagonist (metoclopramide) as second-line antiemetic |

– |

Level 2++, Grade B |

Level II-2, Grade B |

– |

| Add acid suppression therapy |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Diazepam is not suitable for management for NVP or HG |

– |

Level 1, Grade B |

– |

– |

| Ondansetron is used as an adjunctive therapy for severe cases of NVP or HG |

LOE-II |

Level 2++, Grade C |

Level II-1, Grade C |

– |

| Phenothiazines is an alternative for severe NVP or HG |

– |

– |

Level I, Grade A |

– |

| Refractory NVP or HG |

Add corticosteroids in addition to other antiemetics |

LOE-I |

Level 1+, Grade A |

– |

Level B |

| Enteral tube feeding (nasogastric or nasoduodenal) is used for women who are not responsive to medical therapy and unable to maintain their weight |

LOE-III |

Level 2++, Grade D |

– |

Level C |

| Total parenteral nutrition as the last resort in management of refractory NVP or HG |

– |

Level 2+, Grade D |

– |

Level C |

| Investigations of other potential causes should be carried out in refractory cases |

LOE-III |

– |

Level III, Grade A |

– |

| Complementary therapies |

Ginger |

LOE-II |

Level 1++, Grade A |

Level I, Grade A |

Level B |

| Acupressure and acupuncture |

LOE-II |

Level 1+, Grade B |

Level I, Grade B |

– |

| Hypnotic therapies are not recommended |

LOE-I |

Level 3, Grade D |

– |

– |

| Further management |

Termination of pregnancy |

LOE-III |

Level 3, Grade D |

– |

– |

| Helicobacter pylori eradication |

LOE-III |

Level 2+ |

– |

– |

| –, absence of level of evidence and grade of recommendations; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; HG, hyperemesis gravidarum; LOE, level of evidence; NVP; nausea and vomiting in pregnancy; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; SOGC, Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada; SOMANZ, Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand |

Discussion

This study examined the quality of four published CPGs on managing HG. The purpose of this review was to examine the quality of the process of developing these CPGs and their recommendations using the AGREE II protocol.8 The scope and breadth of recommendations of care in HG covered in these guidelines varied to a small extent.

Comparing the AGREE II scores

The CPG developed by the RCOG13 scored the highest overall score of 83.3%; that is,16.6% more than two others, tied at second. It also scored the highest on all the sections except ‘applicability’, where it was a close second. It is the only CPG that is recommended without modifications. The CPGs produced by the ACOG5 and SOGC12 had a similar overall score, at 66.7%. However, the CPG by SOGC12 scored almost 10% or more in various domains, making it a more reliable CPG than the former. It is worth noting that although the CPG by SOMANZ14 had the lowest overall score and scored poorly on multiple sections, it scored the highest for applicability and the second highest for editorial independence.

Comparing clarity of presentation and scope and purpose

The primary purpose of CPGs is for standardising best care, and their applicability to clinical practice. The SOMANZ14 guideline would require further review in this domain when compared with the other three guidelines. In general, the ‘scope and purpose’ domain scored adequately well, followed by the ‘rigour of development’ domain. For the latter domain, scoring highly is reassuring as the method employed in creating these CPGs is a good indication of the quality of the recommendations. Three (RCOG,13 SOCG,12 ACOG5) of the guidelines listed their purpose and objective with regards to the development of clinical guidelines for HG, which is to provide clear information about diagnosis of and clinical management of HG.

Editorial independence, applicability and stakeholder involvement

‘Editorial independence’ was the poorest scoring domain. This could be a cause for concern regarding conflict of interest. The ‘applicability’ and ‘stakeholder involvement’ domains scored poorly as well. None of the CPGs have a section on applicability nor go into details of how the recommendations should be implemented. The RCOG13 scores the highest, but it is worth noting that SOMANZ14 details how stakeholders were involved in its ‘Methods’ section, and who these stakeholders were. They even included women who have previous experience with NVP or HG.

Recommendations

When comparing the ‘recommendations’ made by each of the four CPGs, eradication of Helicobacter pylori and use of oral ginger are suggested by all four CPGs. All the guidelines recommend ruling out H. pylori infection before diagnosing NVP because of their known association.15,16 Its eradication with triple therapy is considered safe in pregnancy, albeit with studies ranging from Level 2+ to level of evidence (LOE) III. The other recommendation that is supported by all four CPGs is the use of ginger for mild-to-moderate NVP. This is Grade A evidence, cited by RCOG13 and SOGC,12 the former being (1++). Data have shown its effectiveness is comparable to vitamin B6.17–19 Ginger is said to improve gastrointestinal motility, as the effect on cholinergic M3 receptors and serotonergic 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors in the gut is weak. The recommended dosage as stated by SOGC12 and SOMANZ14 is 250 mg by mouth four times per day, preferably taken in standardised products rather than in food.

Metoclopramide is a widely used antiemetic for patients hospitalised for NVP as it is safe, effective and economical.12 This recommendation is cited as Grade II-2B in SOGC12 and Grade B in RCOG.13 Doxylamine is an antihistamine that is often used in combination with pyridoxine, as studies have shown that this combination is far more effective than pyridoxine alone.13 In all four CPGs, a combination of pyridoxine and doxylamine is suggested as the first-line treatment for NVP, ranging from moderate to strong levels of evidence.

Acupressure and acupuncture therapy are recommendations that are supported by three guidelines. However, their use has conflicting results.5,20,21 ACOG5 comments that although numerous studies report a benefit, the methodologies of these studies have significant flaws. No benefit was proven in two large trials in comparison to sham stimulation. Overall, acupressure at the pericardium 6 (Nei Guan P6) point has shown limited benefit in relieving nausea and episodes of vomiting, whereas acupuncture has shown no benefit over placebo.5

The role of ondansetron as adjunctive therapy for severe cases of NVP and HG18 is supported by moderate evidence of LOE-II and Grade C. The consensus is that, as a result of the risk of congenital malformation, ondansetron is implemented as second-line therapy.22 For these reasons, individuals who are not successfully treated with antiemetics such as antihistamines and phenothiazines would be more suitable to receive ondansetron, which should be given ideally after the first trimester of pregnancy with adequate counselling.

The use of corticosteroids has garnered some controversy, as some studies report a higher incidence of cleft lip, regardless of the presence of cleft palate, although a large retrospective study of inhaled steroids showed no association.5,13 A recent meta-analysis has revealed no clear benefits of corticosteroids in HG was reported except in small studies.23 However, SOMANZ14 and RCOG,13 citing evidence of LOE-I and Level 1+, recommend the use of corticosteroids when intravenous fluid replacement and regular antiemetics have failed. Steroid therapy in indicated cases has shown a lower rate of rehospitalisation.

Enteral tube feeding is supported by at least three CPGs in women who are not responsive to medical therapy and unable to maintain their bodyweight. Although the evidence is of low quality, enteral tube feeding is to be considered in a multidisciplinary approach, when all other medical therapies have failed. Its effectiveness is not well established. Sometimes increases in nausea and vomiting occur, especially in the long term.24

Constant monitoring is mandatory for total parenteral feeding, which is complex and invasive. The disadvantages of total parenteral feeding are its high cost, inconvenience and potential serious complications, such as thrombosis and infection. Although the evidence is Level 2+, parenteral feeding is associated with reduced perinatal morbidity risk. Ensuring sufficient calorie intake would be effective in patients who are refractory to conventional management strategies.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. We only included CPGs published in English. These guidelines are widely published in PubMed, Web of Science and Science Direct. They represent easily accessible references for medical practitioners and are widely used in the clinical practice of many English-speaking countries. There could be several other guidelines that have been published in non-English language but were not evaluated in this study. Dobrescu et al suggested the influence of excluding non-English in most medical topics is inconsequential to the overall results.25

Another limitation would be the use of the AGREE II instrument as a standardised method and rating tool in this study. The assumption of the importance of all domains being equal for determining high-quality guidelines has been pointed to be one of the shortcomings of this checklist. Rigour of guideline development and editorial independence were found to influence assessors more, compared with the other domains.26 On the basis of our experience, we suggest that rigour of development, applicability and clarity of presentation should be emphasised in the production of the next generation of the AGREE II tool. Besides that, as Hoffmann-Eßer suggested, the lack of clear distinction between low and quality evidence among AGREE II users indicates room for improvement of AGREE II as an appraisal tool.27

Implications

This review leads us to several other implications. Firstly, there needs to be an agreement on the categorisation of NVP and HG. As the ACOG guideline suggests, the ‘definition of HG remains elusive, and it is a diagnosis of exclusion’.5

A standard definition of HG would be the first step to accurately comparing studies and the recommendations proposed for each clinical scenario. Regardless, all guidelines unanimously recommend the use of the Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) score to evaluate the severity of NVP. PUQE scores are useful in triaging patients and assist practitioners in determining severity of NVP and HG. Another stark point that is made by comparing the CPGs is the importance of home remedies and complementary treatment, in particular the use of ginger (250 mg four times a day). The evidence suggests it has a role in reducing the use of pharmacological treatment for mild NVP.

Dietary changes; small, frequent meals with high-protein, low-fat snacks; sour or carbonated drinks; and sucking on lemons are often advised but are not formally addressed in CPGs.

The CPGs do not address other factors associated with NVP and HG. A dose-dependent relationship of oestrogen and human chorionic gonadotrophin has been alluded to in the development of NVP and HG. This would be an area for further review. Literature indicates the multifactorial basis of NVP and HG. Some of the proposed hypotheses include psychological factors, evolutionary adaptation and possible genetic inheritance. Well-designed studies in these areas may produce robust data to improve existing CPGs. The findings of a study by Kjeldgaard et al suggest that women with HG are at a higher risk of developing emotional distress when compared with women without HG. This is seen from the 17th gestational week up to 18 months after birth.28 The intensity and duration of HG symptoms is intrinsically related to psychological impact of HG on and after pregnancy.

Conclusion

The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum, published by RCOG,13 best fits the criteria for good clinical practice according to AGREE II. The synthesis of all four CPGs suggested similar management for HG with minor differences. More robust data are required in evaluating the multifactorial basis for NVP and HP. Medical practitioners could use the guiding principles of management on the basis of the needs of individual patients.