Endometriosis can affect women who have transitioned to men and non-binary people; however, most of the evidence available is based upon cis women, hence the use of the term ‘woman’ or ‘women’ throughout this paper.

Estimates of the prevalence of endometriosis in Australia suggest that one in nine women are affected, with increasing rates potentially reflecting raised awareness, reporting and diagnosis.1 Diagnosing endometriosis can be challenging, with an average delay to diagnosis of seven years.2 Efforts to reduce diagnostic delay, with the aim of reducing the physical, emotional and psychosocial impact of endometriosis on the lives of women, have culminated in the development of the National action plan for endometriosis,3 representing a coordinated approach to improve the quality of life for Australian women with endometriosis through a series of structured strategies, one of which is to improve awareness, earlier diagnosis and patient-focused care in the primary setting.

Delayed diagnosis in primary care may be due to a multitude of reasons. Symptoms typically associated with endometriosis (dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, dyschezia) may be variable, fluctuate in severity or overlap with other common conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome.4 Women may not seek care under the assumption that painful periods are a normal and expected part of life,5 whereas others may not emphasise the severity of their symptoms to their health providers. Conversely, healthcare professionals may dismiss symptoms6 or attribute these to bowel or psychological problems.2,6 In addition, women can be asymptomatic, with a diagnosis of endometriosis made after its detection by laparoscopy during investigations for infertility.7 However, delays in diagnosis may reflect a period where appropriate investigations and simple management are being undertaken8 and symptomatic relief from initial therapies has not necessitated a referral for laparoscopic diagnosis.9 Further, when referral is needed, delays may occur due to difficulty accessing specialist services.

International studies looking at healthcare perspectives in managing women with endometriosis have highlighted limited understanding, education and training, as well as time constraints.10,11 An Australian study of healthcare professionals and consumers suggests improvements in education and collaborative care, with localised referral pathways having the potential to improve care in those with endometriosis.6 In addition, there is a lack of validated symptom-based screening tools to help with the diagnosis of endometriosis in primary care,8,12 although ongoing research continues to search for ways to address diagnostic delay, and a recent symptom-based scoring system to identify populations at risk seems promising.13 To further our understanding, this study explored the challenges that general practitioners (GPs) face in diagnosing and managing endometriosis in their clinical practice.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted from a sample of nine Western Australian (WA) GPs. This study was approved by The University of Western Australia (2020/ET000056).

Recruitment

To ensure diversity of GP experiences, purposive convenience sampling was used with recruitment through general practices affiliated with The University of Western Australia and the WA Rural Clinical School, allowing for snowball sampling.14 Recruitment aimed at having representation from rural, outer metropolitan and inner metropolitan GPs; male and female participants; early career and experienced GPs; and those with and without specialised women’s health training. Invitations were sent via email to GP networks, and through UWA GP and WA GPO newsletters, with interviews conducted via videoconferencing, telephone and face-to-face between May and November 2021 after written consent had been obtained.

Methodology

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to further understand the phenomenology of clinician experiences. It was felt that this approach could best address the research aim,15 namely obtaining GPs’ perspectives on diagnosing and managing women with endometriosis. In-depth semistructured interviews of 45–60 minutes in duration were used to collect demographic details and to address topics around knowledge and experiences, as well as challenges to the diagnosis and management of endometriosis (see Appendix 1).

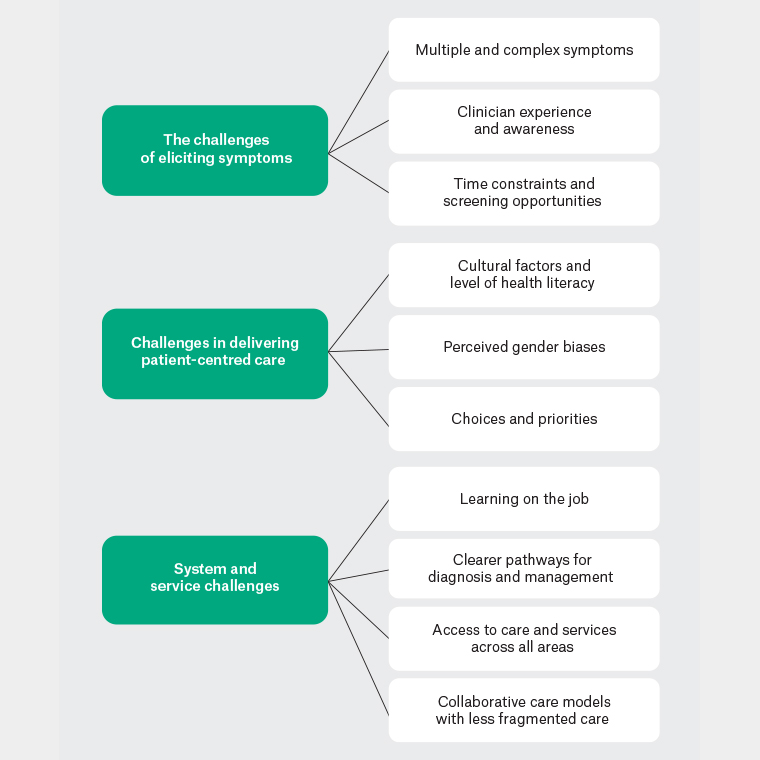

Qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim for inductive analysis in NVivo 12 (QSR International, Denver, CO, USA), with participant responses deidentified (P1–9). Interviews were conducted by the lead author (JF), a GP with an interest in women’s health. Reflexive thematic analysis occurred after each interview, with data familiarisation, coding and the generation of initial themes and subthemes independently undertaken by two authors (JF and TM). Saturation was reached and defined as the point at which limited new concepts or descriptions relevant to the research aim were found.16 Further development and reviewing of themes and the refining and defining theme labels occurred,17 resulting in a thematic map (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thematic mapping: Challenges for general practitioners in diagnosing and managing endometriosis.

Results

The demographic details of nine participants are presented in Table 1. The participants were predominantly metropolitan and female GPs who were mid-career. Three main themes were identified: challenges of eliciting symptoms; challenges in delivering patient-centred care; and system and service challenges.

| Table 1. Demographic characteristics of general practitioner participants |

| Participant ID |

Qualifications |

Practice |

Sex |

Age group (years) |

| P1 |

GP, GP Obstetrician, Advanced Diploma Obstetrics |

Rural, regional |

Female |

36–40 |

| P2 |

GP |

Metropolitan |

Female |

46–50 |

| P3 |

GP |

Metropolitan |

Female |

41–45 |

| P4 |

GP, Diploma Obstetrics, Reproductive and Sexual Health |

Outer metropolitan |

Female |

46–50 |

| P5 |

GP, Advanced Diploma Obstetrics |

Metropolitan |

Female |

51+ |

| P6 |

GP |

Metropolitan |

Male |

31–35 |

| P7 |

GP, Advanced Diploma Obstetrics |

Metropolitan |

Female |

46–50 |

| P8 |

GP, Diploma Obstetrics |

Metropolitan |

Female |

51+ |

| P9 |

GP Registrar |

Metropolitan |

Male |

26–30 |

| GP, general practitioner. |

Challenges of eliciting symptoms

Overwhelmingly, participants reported difficulties eliciting symptoms to help in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Three subthemes were identified within this theme: multiple and complex symptoms; clinician experience and awareness; and screening opportunities and time constraints.

Multiple and complex symptoms

The symptoms specific to endometriosis can represent many differential diagnoses:

There’s so many things that can cause the symptoms ... so many possibilities in terms of diagnosis. (P4)

They can also overlap with non-gynaecological conditions:

… can present like irritable bowel syndrome … fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome … it can be quite difficult to tease out what’s going on and what the priorities are for treatment. (P1)

When people presented with multiple complaints, there were potentially missed opportunities for diagnosis:

It’s easy to miss … partly because in general practice people come with so many problems to each consult. (P5)

Even with suspected endometriosis, it remains difficult to diagnose:

It can be challenging in getting a definitive diagnosis … it’s not always easy to actually define that on an investigation. (P4)

Regardless, taking time to elicit a history and acknowledge the issues were important:

… listening to women and hearing their stories, and symptoms that are impacting on them and validating them. (P1)

Clinician experience and awareness

Most respondents felt clinician experience was important, particularly for those less experienced in women’s health:

It comes down to how many cases we see, the more we see the better we get … this affects my confidence, knowledge, and pattern recognition skills. (P6)

Increased awareness of endometriosis as a common diagnosis helped:

I feel confident in the sense that I’m always thinking about it. (P4)

However, limitations were thought to occur when women did not present with classic symptoms or did not disclose menstrual concerns.

Despite endometriosis being recognised as important, perceptions, biases and, hence, clinical practice varied between each of our participants based on their experiences. For example, the diagnosis of endometriosis in young women is potentially clouded by the frequency with which symptoms were reported within that population:

How often do young women present with dysmenorrhoea? Often. (P2)

and by the misunderstanding of what is perceived as normal:

Women come in with pain and have the misconception that it is normal. (P3)

Chronic pain was viewed as separate and associated with notions of stigma:

Chronic pelvic pain … I think that really does impact the care that women receive and the way that they are investigated and the treatment they receive. (P1)

Time constraints and screening opportunities

Time constraints in general practice were commonly reported, and endometriosis, often associated with complex symptomatology, can mean longer or multiple appointments are needed:

To elicit the history itself is difficult … to ask the question, have you got dyspareunia … a long process with potentially quite a few appointments. (P7)

This was thought to be problematic:

… particularly female GPs being time poor, … you’ll get the painful periods thrown in … (P5)

and was managed with longer appointment times and increased remuneration for complex consultations:

It’s often rushed … chronic women’s health issues, and it’s not remunerated equally. (P1)

Reduced opportunities for menstrual health screening were thought to exist due to perceived time constraints:

The patients don’t want to talk about their periods or don’t initiate conversations about their periods … we tend to do it just based on their presentation. (P8)

Routinely incorporating endometriosis questions into practice may help:

You have to seek (symptoms) out … we are losing opportunities to … just talk about gynae(cological) stuff. (P5)

Challenges in delivering patient-centred care

Participants felt that patients’ individual circumstances influenced their consultations. This challenge of delivering patient-centred care had three subthemes: cultural factors and level of health literary; perceived gender biases; and choices and priorities.

Cultural factors and level of health literacy

Discussions on menstruation were challenging:

Women’s health has been very taboo … I think women find it very difficult to talk about. (P1)

including with women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds:

Now that we’ve got more women coming from other cultures, I don’t think [endometriosis] is something that is even suspected. (P7)

Poor health literacy was considered another challenge, with many women perceived to lack an understanding of normal menstrual symptoms:

Women’s knowledge of their own health in terms of their reproductive health, I think is limited. (P1)

… one of the barriers might be patients not actually recognising their symptoms. (P9)

A lack of understanding of management when being treated for possible or confirmed endometriosis could also create challenges:

… to convince them we are using the contraceptive pill for a different purpose here is not easy. (P7)

Conversely, increasing health literacy and peer support were thought to positively influence women’s clinical experiences:

Having the Internet and women being able to go out and do their own research ... women are becoming more empowered to seek the help that they need. (P1)

Perceived gender biases

Male participants perceived gender biases:

Rarely do they come in with (menstrual problems) as their primary issue … maybe women feel more comfortable talking to other women. (P9)

Sometimes when I ask questions, they say ‘That’s all good’, but when they see a female GP, they are more likely to open up. (P6)

Gender also impacted referral for investigations and specialist care:

To have an ultrasound done by a male sonographer, … or if there is a need for the sonologist to come in and actually visualise, then it gets really tricky. (P7)

Choices and priorities

Patient-centred care is practiced, with participants supportive of women making informed choices. This was noticeable when it came to referral for laparoscopy:

Diagnosis as it stands is quite an invasive process … to get a laparoscopy, often women don’t really want to have a general anaesthetic and a surgical procedure if they can avoid it. (P1)

While supporting choice, consideration of the life stage, especially if pregnancy was desired, affected discussions:

I would offer referral to the gynaecologist … and the patient would work out whether they thought they needed to go. I wouldn’t strongly urge them … unless they’re trying to fall pregnant. (P8)

I guess it depends on the woman’s personal choice … confirming the diagnosis with laparoscopy, or we could simply just treat to begin with. (P7)

Some saw women as viewing their symptoms as non-problematic, with others juggling symptoms with competing life and health priorities:

…because they’ve had these other things that are important. (P3)

Mainly women in the reproductive age group have got busy lives. Many of them are mothers who work … actually, even finding time to go an appointment, they don’t put themselves first, so they will just go with a bad day and put up with pain rather than looking after or getting to a solution. (P5)

System and service challenges

Within this theme, four subthemes were identified: learning on the job; the need for clearer pathways for diagnosis and management; access to care and services, including investigations and management; and collaborative care models with less fragmented care.

Learning on the job

All participants reported limited educational exposure to endometriosis:

… briefly in medical school during obstetrics and gynae(cology) terms we had some teaching on endometriosis. (P9)

… it’s only been since starting my GP training. (P6)

Postgraduate training and self-educational activates increased knowledge:

I’ve been trying to sort my own learning around this. (P1)

However, GPs also learned from being involved in patient care with specialist feedback:

…learning from patients, and how they’re treated. (P8)

Need for clearer pathways for diagnosis and management

GPs want practical and easy-to-follow guidance on when and how to diagnose and treat endometriosis, including streamlined referral pathways:

There’s not a very easy guideline to go too … it actually can be quite disheartening. (P3)

Further, GPs wanted clarification as to when they needed to establish a diagnosis, when to refer or when they could manage without a confirmed diagnosis:

I find it a little challenging on exactly how to clarify the diagnosis and the severity … I don’t know where I can say ‘this is endometriosis’, or it’s definitely not. I think that’s what’s hard. (P8)

Our participants were treating women for their symptoms without a clear diagnosis, but were uncertain if this was correct:

Do they need that diagnosis? … We already manage their pain and bleeding. (P3)

or of the potential harm of this approach:

Whether that’s doing any harm to not to clarify the diagnosis, honestly, I don’t know … you just manage them based on how they present. (P8)

Additional management challenges existed when first-line treatments did not work or were not tolerated:

There’s lots of reasons why women can’t take the pill, or won’t take the pill, or won’t have a Mirena, … so they’re the challenges. (P2)

Access to care and services across all areas

Barriers to accessing care occurred at multiple levels, including appointments to work through the diagnosis and preliminary management:

…it takes a few consultations to get to that point…to get the appropriate investigations are not easy. (P7)

Other barriers to accessing care included the limited provision of specialised ultrasound services, increased costs, time and travel distances:

… some patients must travel a bit to go. (P4)

My working practice has a majority of healthcare card holders, so people who can’t afford to pay. (P5)

Further, there were barriers to women accessing timely laparoscopic services for both diagnosis and management:

… requires specialist gynae(cologist) input, which can be difficult to access in itself. (P9)

There was perceived disparity between public and private gynaecological services:

In the public system, waiting times to see gynaecologists are long, and people get lost in the wait. (P5)

The public system can be a bit slow and delayed in getting treatment and getting reviews or referrals accepted. (P9)

There was uncertainty where the best care was delivered:

How do I know if I am referring to the right people? (P8)

This included reduced access to specialist endometriosis gynaecological services:

If you’re looking for a specialist whose area of expertise is in endometriosis, we’ve only got a few in this state. The rural women have to join the queue. (P1)

Collaborative care models with less fragmented care

Participants felt improvements would occur with a collaborative model of care:

If it’s managed by a GP and a team that understands the condition, work collaboratively, and have a holistic approach to the women’s health and wellbeing, then you know you can get good outcomes. (P1)

Fragmentation occurs when women are referred to specialists with GPs not feeling included in ongoing care:

Once they go to specialists, once they’ve been diagnosed with (endometriosis) and they have been managed I don’t think they actually come back. (P7)

I think people fall through the cracks all the time. (P5)

Discussion

This qualitative study explored the challenges that exist within current general practice in diagnosing and managing women with endometriosis. Three broad challenges were identified: in eliciting symptoms, delivering patient-centred care and within the current system and services. The challenges seen in this study are common to other complex chronic diseases,18 but highlight the difficulties GPs face in navigating diagnostic uncertainty, cultural and health literacy, and perceived gender biases. It is widely recognised that significant improvement in outcomes for individuals affected by endometriosis is required, and this will be facilitated by raising awareness among women and health professionals. The implementation of strategies to reduce delays in diagnosis and improved symptom management will hopefully reduce the health and economic impacts3 of this complex disease and draw on elements from our findings.

The findings of the present study suggest that eliciting symptoms is difficult. Women can present with multiple and complex symptoms that may go unrecognised or may be thought not indicative of endometriosis. A GP-based case-control study comparing symptomology between those with a diagnosis of endometriosis and those without suggests that although abdominal pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea and menorrhagia were more common, coexisting diagnoses like irritable bowel conditions or pelvic inflammatory disease were also frequent, with uncertainty as to whether this was a result of coexisting conditions or misdiagnosis.19 It remains difficult to determine the significance of a myriad of symptoms, with multiple symptoms often associated with dysmenorrhoea, regardless of endometriosis diagnosis.20

We found clinician experience and awareness of the possibility of endometriosis helped. Raising awareness in health professionals is the first priority of the National action plan for endometriosis3 and seems likely to be an effective strategy. Many biases exist that potentially influence diagnostic reasoning and affect clinician interactions with individual patients, including the frequency of diagnosis or misdiagnosis.21 An example of this is that dysmenorrhoea is reported by 88% of young women in Australia,22 and it is therefore understandable that GPs may tolerate associated diagnostic uncertainty or believe symptoms are less likely to be related to endometriosis. Challenging these biases in practice requires greater allocation of time and resources. Individuals affected by endometriosis often have various symptoms,8 and multiple consultations are needed to sort through this complex symptomatology. A lack of understanding of this, alongside financial and time constraints and reduced screening opportunities, adds to the challenge.

Patient-centred care is integral to general practice and improves patient satisfaction and outcomes,23 but it is difficult to get the balance right. Our interviews showed that GPs were very cognisant of this when supporting women in their choices, especially in dealing with dilemmas arising from a laparoscopic investigation to facilitate diagnosis and treatment of possible or suspected endometriosis. Despite recommendations for laparoscopy in those with suspected endometriosis,24 all GPs interviewed recounted managing discussions around patient choice regarding this procedure, or managing competing priorities (health or otherwise), which are all known contributors to diagnostic delay.25 Further to patient-centred care, there were significant challenges to navigating cultural factors, gender bias and varying levels of health literacy. Increasing health literacy is beneficial to women’s knowledge of their reproductive health, and although other reasons exist for women not seeking healthcare for menstrual symptoms,5 low health literacy can increase avoidant behaviour.26 Improving menstrual health literacy in different cultural communities and educating younger women, such as in school programs, might, over time, reduce this issue for clinicians.

Concerns were highlighted in this study about system and service challenges. Formalised education of GPs is essential, and is currently lacking for even GPs experienced in women’s health. GPs learn through patients, experience and self-educative practices. There have been calls for GPs to be an active part of multidisciplinary teams caring for people with chronic health conditions, and this should be the case for endometriosis,6 with the added potential for educational benefits within a collaborative model of care. Further, GPs identified perceived barriers to women accessing cost-effective, timely and gender-specific care across multiple levels of the healthcare system. Future translational consumer-driven research may explore ways to address these barriers with maximum impact.

The GPs in our study overwhelmingly want pragmatic and clear guidance on pathways for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis, with many facing uncertainty in this domain. Australian clinical practice guidelines on endometriosis released in 2021 may help address some of these issues,27 but guidance at a local level is essential. Future research in endometriosis incorporating primary care is needed,3 targeting evidence gaps with best clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

The small sample size of GPs interviewed in this study, while potentially reducing generalisability, aligns with existing Australian research and other international qualitative studies in this field. The research methodology allowed for variation in sampling to get a maximum representation of demographic spread with the resources available. Despite this, differences in experience arose between the two male and seven female participants that would benefit from further exploration. Further, the challenges facing GPs are similar for those with and without women’s health qualifications. The use of rich descriptions provides contextual information on the experiences of GP participants, thus allowing deeper insight into the meaning underpinning the research findings. By exposing participants to the research aim and via their participation, self-reflection was promoted further, enhancing the educative authenticity of this study.

Conclusion

GPs experience multiple challenges in the diagnosis and management of individuals with endometriosis. GPs can be better supported through heightened awareness, education (with the understanding that endometriosis is a complex chronic condition requiring adequate funding processes), clear and pragmatic guidelines that consider local pathways and increased access for referral to centres for excellent and collaborative care.