Case

Mdm Q was a 71-year-old retired hawker who first presented to a primary care practice two years earlier with short-term memory difficulties, such as misplacing things without independent retrieval and forgetting recent conversations. She had no aphasia, agnosia or apraxia. She used written reminders of the time to pick up her granddaughter from school and was otherwise independent in instrumental activities of daily living (iADL). Physical examination, including full neurological examination, was normal.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) revealed modest cognitive impairment, with a score of 19/30. Tests for reversible causes of cognitive impairment, including full blood count, vitamin B12/folate, magnesium/phosphate/calcium, liver/renal/thyroid function and urinalysis, were normal. She had no significant medical history and no past personal or family history of dementia or psychiatric conditions.

She defaulted follow-up but returned to the practice after two years with worsening memory symptoms, a three-point drop in the MMSE and recent-onset visual hallucinations (VH). The VH started as visual distortions, such as seeing zebra crossings as wavy lines, and evolved to vivid, well-formed VH of children and adults that were disturbing. No hallucinations in other sensory modalities were experienced. She did not take any analgesics or sleep supplements. Examination by an ophthalmologist did not find any ocular explanation for the VH.

Question 1

What are the common causes of VH in older people?

Question 2

Did Mdm Q have delirium? Otherwise, did she suffer from dementia?

Question 3

How would you manage Mdm Q when she returned with worsened cognition and VH?

Answer 1

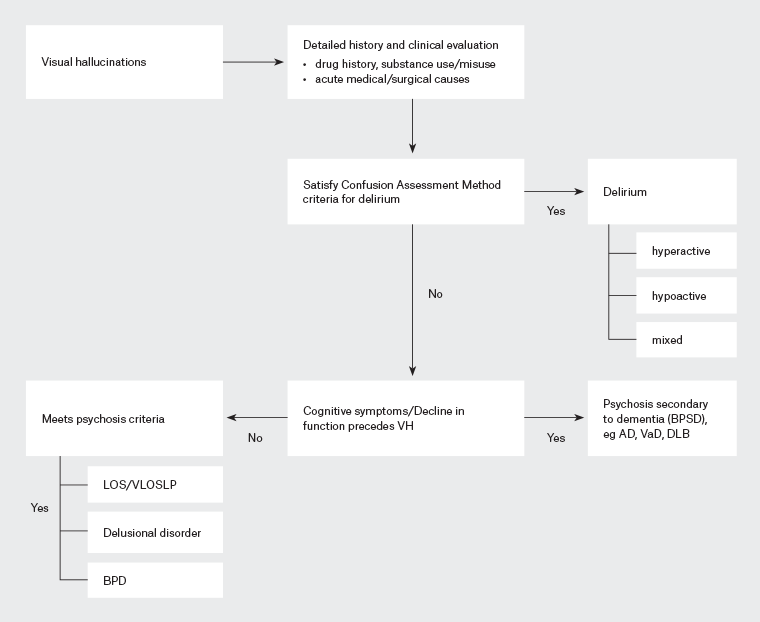

VH in older people can be simple or complex and have myriad casuses1 (Table 1). Where VH are associated with delusional thinking, one would need to differentiate between psychoses or behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). As much as 40% of psychotic symptoms in older people can be due to dementia.2 If psychotic symptoms are present with no or minimal cognitive symptoms and intact iADL, consider primary psychiatric conditions and secondary psychosis in older people.2–4 An approach to VH is presented in Figure 1.

| Table 1. Some possible causes of visual hallucinations in older people |

| Charles Bonnet syndrome |

- Cataracts

- Glaucoma

- Macular degeneration

|

| Delirium |

- Due to acute medical/surgical illness

- Medication induced

- Metabolic disturbance

|

| Neurodegenerative conditions |

- Alzheimer’s dementia, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies

|

| Neurological causes |

- Parkinson’s disease

- Epilepsy

- Migraine

|

| Substance/alcohol use/abuse |

- Substance-induced/alcoholic hallucinosis

|

| Psychiatric conditions |

- Late-onset psychosis (onset after age 40 years)

- Very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (onset after age 60 years)

- Bipolar affective disorder

- Delusional disorders

|

| Others |

|

Figure 1. Approach for evaluating visual hallucinations (VH). If there is a clinical psychosis presentation, look for criteria of delirium. If there is no delirium, evaluate the patient for substance/drug-induced psychosis and psychosis caused by acute medical conditions, including autoimmune causes. If no causes are evident and the condition does not meet the criteria for dementia, then it is likely a functional psychosis. If dementia is established, the psychosis is a manifestation of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). Click here to enlarge

AD, Alzheimer’s dementia; BPD, bipolar affective disorder; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; LOS, late-onset schizophrenia; VaD, vascular dementia; VLOSLP, very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis.

Answer 2

The confusion assessment method5 is useful as a quick assessment tool in the busy primary care setting. To diagnose delirium, an acute onset with fluctuating course and inattention must be accompanied with disorganised speech/behaviour and/or a change in alertness. Mdm Q did not manifest inattention, disorganised thinking or altered levels of alertness. By the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition criteria,6 Mdm Q did not have dementia when she initially presented with vivid and distressing VH because her iADL were largely intact.

Answer 3

A detailed but focused history and physical examination should be conducted to ascertain whether Mdm Q had delirium precipitated by an acute medical condition, drug causes (including substance/alcohol use/abuse) or an acute psychiatric illness. These conditions would require urgent referral to an emergency service.

Case continued

With no indication for urgent referral, Mdm Q was managed with non-pharmacological measures, assisted with gaining insight into the VH and counselled on measures that would slow cognitive decline. Apart from a review consultation with the primary care doctor, an early psychiatric consultation was also arranged.

However, Mdm Q presented a week later at the hospital’s emergency department because she was distressed and agitated from the increasingly well-formed VH. She was admitted for delirium work-up and discharged with a diagnosis of and treatment for Alzheimer’s dementia with BPSD. Despite treatment, distressing VH persisted, Mdm Q was often disorientated and her cognition fluctuated, especially at night, leading to multiple admissions. No rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder was observed. Physical examination was unremarkable, with no Parkinsonism, and all investigations for delirium at each hospitalisation were negative, including magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain. The diagnosis for these admissions was Alzheimer’s dementia with BPSD.

Over the course of one year, the VH increased in frequency and intensity while Mdm Q gradually became impaired in iADL and was unable to go grocery shopping. Mdm Q could not navigate home from places she frequented and was unable to organise house chores and cooking or help with the care of her granddaughter.

Question 4

When Mdm Q was first diagnosed with dementia, was it Alzheimer’s dementia?

Answer 4

Although Mdm Q had amnestic symptoms at initial presentation, her iADL were still intact, implying early disease. She soon developed recurrent, distressing VH and disorientation that led to multiple admissions, where she was first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia with BPSD. The Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis is highly questionable because VH are uncommon in early Alzheimer’s dementia, unlike dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).7 VH are the most common form of hallucinations in individuals with dementia and tend to emerge when dementia progresses in severity.8 However, Mdm Q had vivid VH while in the dementia prodromal stage, accompanied by prominent cognitive fluctuations early in her disease course. The latter is regarded as the most distinctive feature of DLB.9 When Mdm Q progressed to dementia, she satisfied two core clinical criteria for probable DLB in VH and fluctuations. According to Budson and Solomon, ‘actual well-formed hallucinations of people or animals are simply not present in other disorders’.10

Key points

- DLB is often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s dementia, with the risk of inappropriate antipsychotic use considering neuroleptic sensitivity in DLB.

- Misdiagnosis causes delay in providing good care because the disease trajectory and care needs of DLB are vastly different from Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Consider the differential diagnosis of evolving DLB when there is mild cognitive impairment with VH, unexplained/unprovoked or recurrent delirium or late-onset psychosis symptoms because prodromal DLB can present with the onset of delirium or psychosis.