Central to the success of the Australian General Practice Training Program is a general practitioner (GP) supervisor, positioned as the backbone of general practice training, who should lead a supervisory team within a high-quality clinical learning environment.1 Although general practice training is generally well rated by registrars,2 concerns have been raised about the variable quality of GP supervision and the impact of negative training experiences on registrars,3 particularly where the level of support fails to match the registrars’ needs.4

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) Standards for general practice training require professional development (PD) activities to be ‘tailored to the needs of the supervisor’ and support ‘the supervision team in undertaking and developing their supervisory role(s)’.5

Since general practice training was regionalised, there have been two clarion calls for changes in GP supervisor PD. Thomson et al argued in 2011 that ‘business as usual’ would not meet the swelling demand for skilled GP supervisors.6 Among other recommendations, they called for in-practice peer learning and the development and support of the teaching team in the practice. In 2015, Morgan et al described GP supervisor workshop programs as ‘ad hoc and disconnected’ and proposed the development of a national curriculum for GP supervisors.7

This article examines current supervisor PD programs provided by regional training organisations (RTOs) in Australia and considers whether they are meeting the RACGP’s training standards and if they have responded to the 2011 and 2015 calls for change. The authors then present a novel approach they have developed to address the identified weaknesses.

Current GP supervisor professional development

Table 1 contains a summary of each of the supervisor PD programs provided by current RTOs, obtained from publicly available documents and webpages followed by interview or correspondence with senior RTO medical educators. Programs for new supervisors are a common feature, but further learning content and requirements differ significantly.

| Table 1. Supervisor professional development for lead supervisor in Australian regional training organisations |

| Regional training organisation |

Supervisor professional development (PD) program |

Eastern Victoria General Practice Training24

|

- Mandatory completion of cultural awareness education

- New supervisors complete four foundation modules (asynchronous online and workshop learning) prior to accreditation

- Completion of six core modules (asynchronous online and workshop learning) over the following three years

- Thereafter, a specified PD activity must be completed by each supervisor each year

- Activity requirement rather than time requirement for supervisors

|

| General Practice Training Queensland25 |

- Introductory workshop before first registrar

- Large range of PD opportunities

- Each supervisor must complete at least one hour of PD per year

- Total practice supervisor PD requirement depends on number of supervisors: 12, 18 or 24 hours

|

| General Practice Training Tasmania26 |

- Initial training full-day workshop for new supervisors

- Ongoing workshop and webinar program

- Other PD activities (General Practice Supervisors Australia) recommended

- One activity per supervisor per year; no hours mandated; no upper limit

|

| GP Synergy27 |

- Introductory workshop plus online orientation course before first registrar and completion of a further workshop within the first 12 months

- Ongoing PD workshops provided

- Other specified PD activities are accepted as contributing to PD

- One supervisor per practice per year required to attend regional workshop

- Every supervisor to complete one educational activity per three years

|

| GPEx28 |

- New supervisor full-day workshop within first 12 months

- Compulsory online modules – ModMed Mastering Supervision course

- Accepted PD activities include training visits and examining

- Compulsory six hours of PD per practice

|

| James Cook University (JCU) General Practice Training29 |

- Introductory workshop for new supervisors

- Ongoing workshops and webinars

- JCU course (micro-credentialled) 2.5 days; offered but not compulsory

- Nine hours of PD per annum expected per practice; six hours must be JCU activities; other specified activities accepted

|

| Murray City Coast Country GP Training9 |

- New supervisor workshop prior to accreditation as a supervisor

- Four mandatory asynchronous 90-minute online modules over an 18-month cycle

- Additional compulsory workshop attendance for at least one supervisor each practice each year

- Other PD activities encouraged

|

| Northern Territory General Practice Education30 |

- Mandatory foundation workshop for newly accredited supervisors and offered one hour in-practice induction before registrar commences

- Regional supervisor workshops twice per year

- One workshop per supervisor per two years is required

|

| Western Australia General Practice Education and Training31 |

- Introductory induction meeting for new supervisors with medical educator and training program advisor prior to registrar commencing; no workshop or module requirement

- At least six hours of supervisor workshop education are provided per year

- Six hours of supervisor PD per year paid to the practice; no individual supervisor requirement.

|

The supervisor PD programs offered by RTOs are largely workshop based. The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that many RTOs have converted their face-to-face workshops to webinars. Four of the nine RTOs complement their workshop programs with online modules that supervisors can complete in their own time. Some RTOs promote online activities, guidelines and resources offered by General Practice Supervisors Australia or the RACGP.

Strengths of current GP supervisor professional development

Workshops are reported by RTOs to have value beyond the delivery of predetermined educational content. They are used to implement education research findings8 and to promote supervisor ‘communities of practice’.9 The latter intent is consistent with the findings of Garth et al that GP supervisors can lead a relatively isolated existence, and workshops help them to feel valued and find meaning in their work. 10 The same article asserts that workshops are important for professional identity formation and networking.

Weaknesses of current GP supervisor professional development

While there is evidence of a more systematic approach in some RTOs to covering the educational needs of GP supervisors, this is still without the guidance of a nationally agreed GP supervisor curriculum.

Current supervisor PD does not appear to be meeting the aforementioned requirement of being ‘tailored to the needs of the supervisor’.5 A learning needs assessment, considered fundamental for effective continuing PD,11 appears to be absent from current programs. One RTO (Western Australian General Practice Education and Training) has reported a survey of its supervisors’ unmet learning needs.12 While this information is useful for determining ‘broad brush’ workshop content for all supervisors, it is different from understanding the learning needs of individual supervisors and tailoring their education accordingly.13

Translation of learning into practice is a well-known challenge for education programs based on workshop learning.14 Most supervisors lack in-practice support to turn the theory and skills learnt at a supervisor PD workshop into their teaching practice. Despite the 2011 recommendations to implement in-practice peer learning strategies and recent research further emphasising the value of peer learning in developing expertise,3 in current RTO programs this is mostly occurring opportunistically. Planned peer learning activities, such as a novel small-group peer learning activity involving observation of videorecorded teaching developed by one RTO, are uncommon.15

Finally, although the importance of the supervisory team is emphasised in the RACGP’s training standards, there is little available evidence that current supervisor PD involves the development of the in-practice supervisory team. It may be that the known complex relationship between RTOs and training practices16 has been an impediment to RTOs developing in-practice improvements. Training practices, similar to all healthcare workplaces, have complex histories and cultures that take time to understand and change.17 Without a clear path to achieve this, the requirement to develop the practice team appears to have been neglected in current programs. Any improvement in the performance of supervisory teams from workshops aimed at individual supervisors appears to be reliant on a ‘trickle-down’ effect.

Addressing the weaknesses in current GP supervisor professional development

In 2020, one RTO (Eastern Victoria General Practice Training) was funded to undertake research into the development of a national curriculum for GP supervisors in all training and workforce programs.18 This work is reported to be continuing as part of the planned transition to profession-led training in 2023.19 The syllabus embedded in a national curriculum will hopefully improve the consistency and quality of supervisor PD delivered through workshops and online modules. Other benefits will flow from a national curriculum, which is a much broader articulation of educational intentions, such as allowing recognition of prior learning when supervisors move between regions or between training and workforce programs.

The authors of this article have designed an intervention to address the three remaining weaknesses identified in current supervisor PD: the lack of individualisation of learning, the difficulty of translating workshop learning into practice and the failure to develop the practice team. The intervention includes a needs analysis to ensure learning is individualised, occurs in the practice to make the implementation of changes immediately possible and can be extended to involve the entire practice team. The intervention was trialled as a feasibility study, refined through action research and submitted for publication.

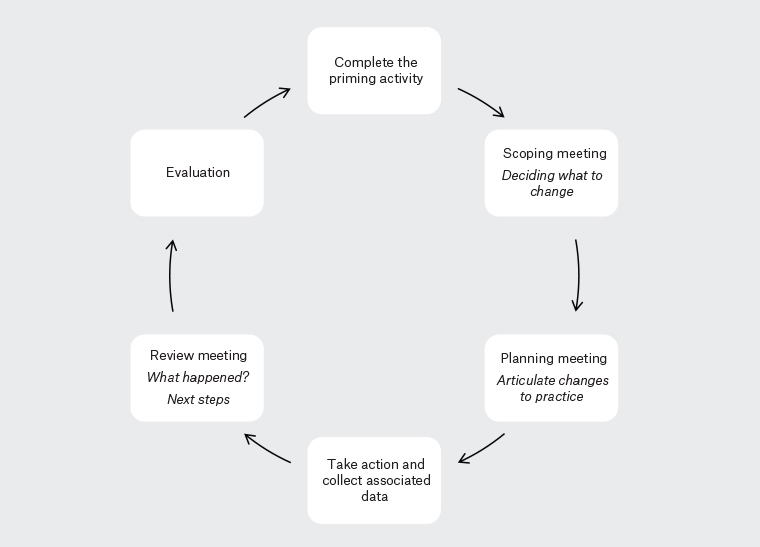

In brief, a medical educator visits the supervisor’s practice to facilitate a quality improvement (QI) cycle. The intervention commences with the lead supervisor completing a priming reflective activity designed to help them identify their PD needs and those of their team as they perceive them. This becomes the ‘QI focus’. From this point, and informed by medical education literature, a bespoke QI action is codesigned by the relevant practice participants with the medical educator. Measurements are formulated to help determine if change has occurred and what can be learnt about the change. Next, the action is undertaken. Finally, a debriefing process reflects on what can be learnt from the action and measurements.

Depending on the issue being worked on, the QI action may involve just the lead supervisor or extend to involve other members of the in-practice supervisory team such as non-lead GP supervisors, nurses, allied health practitioners, cultural educators, receptionists and administrative staff. General practice registrars and other learners in the practice can participate, not just as the recipients of the QI actions, but as partners in proposing actions, collecting measurements and analysing outcomes.

Figure 1 displays the phases of the intervention in the familiar cycle format of QI. A detailed guide for the facilitating medical educator and supervisor is available in the reference provided.20

Figure 1. Phases of the quality improvement intervention

Discussion

We have reviewed the evidence regarding current supervisor PD and compared it with the RACGP’s standards and calls for in-practice peer learning, support of supervisor teams and a national curriculum for GP supervisor PD. A limitation of our analysis is that the programs delivered and experienced by supervisors in RTOs may be different from that espoused in the publicly available documents.

A national curriculum for GP supervisors is currently being completed, and this should aid the delivery of a more consistent and comprehensive PD program. On its own, a national curriculum will not necessarily address the PD needs of individual supervisors and their supervisory teams. Furthermore, if PD remains predominantly workshop based and does not include in-practice peer support, there may continue to be difficulties with translating learning into practice.

An in-practice QI-based approach appears well suited to address the weaknesses we have identified. A QI mindset accepts that there is no single correct way of supervising and teaching, but whatever is being done can be improved. The solutions produced by QI, particularly when prompted by an individual needs analysis, are the ‘tailored’ solutions called for in the standards. A feature of QI activities is their focus on issues that can be acted on immediately in the practice,21 meaning that the barrier to translating learning into practice is readily overcome.

Both education and QI cycles are centred on learning and include phases of planning, action, reflection and analysis that lead incrementally towards improved performance.22 Education has a natural home in improving individual performance, whereas QI can extend beyond this to exploring system improvements.23 This is the basis for expecting an in-practice QI approach to be more successful than current programs based on an education model in supporting and developing the supervisory team.

We are not suggesting that in-practice QI-based PD is a solution for all GP supervisor PD. Instead, we view in-practice QI PD activities as complementary to a well-constructed GP supervisor PD program including workshops and online modules based around a national curriculum for GP supervisors.

In this article, we have presented evidence that current supervisor PD is not meeting the RACGP training standards and outlined an intervention that we have developed to fill the identified weaknesses. It involves a QI approach and is facilitated by a near-peer medical educator. We believe that such a development is fit for the times and fit for purpose and is ready for broader use and further evaluation.