The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health curriculum is eroded by embedded attitudes within the medical workforce that fail to recognise the responsibility of senior clinicians to play a role in improving practice. Contemporary medical education has recognised that the transferable skills of empathy and practical creativity, rather than facts and rote learning, ensure graduation of a well-rounded, self-reflective medical professional.1–4 Nowhere are the skills of adaptability and flexibility more important than in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, where recognition of diversity and applied advocacy are essential. General practitioner (GP) supervisors provide clinical guidance to advanced learners, together with opportunities to foster and promote understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health and influence attitudes.

Aim

We argue the influence of supervisors will improve GP trainees’ application of cultural safety principles for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through a decolonised approach, that ‘seeks to critically consider the assumptions, motivations and values that inform practice’.5 The influence of GP supervisors is critical, as role models, as advocates (for patients and trainees), as active bystanders witnessing racism and as antiracist and decolonising medical practitioners.

Discussion

Community primary healthcare that encompasses, acknowledges and appreciates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health perspectives and culture requires medical school teaching, GP training and continued professional development to address and take measures to reform attitudes and beliefs. GP training follows an apprenticeship model whereby supervisors are tasked with clinical teaching, and can be pivotal in shaping clinical practice and, more importantly, attitudes through the mentorship and role modelling relationship.6,7 These relationships offer opportunities to explore attitudes to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health and provide education. They also offer opportunities to explore attitudes to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health, and supervisor role modelling can promote a decolonised approach, whereby supervisors support a critique of usual practice and the registrar’s establishment of their own approach.

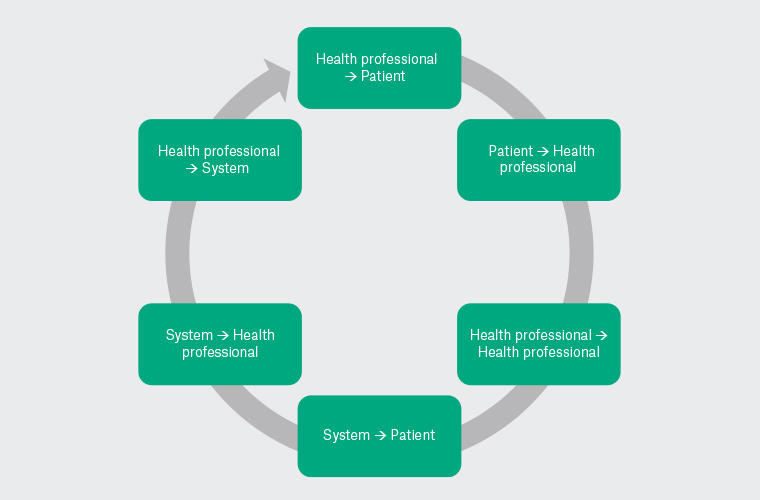

As shown in Figure 1, racism occurs throughout healthcare. Racism is global, and well documented.7–13 Healthcare racism is particularly challenging for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, whose healthcare needs mean frequent and often distressing engagement with racism. We contend that racism cannot be eliminated from healthcare without an antiracist, decolonising approach from medical educators, including GP supervisors. Furthermore, although decolonised practice may be challenging, it is important for practitioners to remember that:

… decolonization does not mean … a total rejection of all theory or research or Western knowledge. Rather it is about centring (Indigenous people’s) concerns and world views and then coming to know and understand theory and research from (those) perspectives.14

Figure 1. Points of racism in healthcare.

The successful integration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medical education, from medical school and beyond, faces the challenges of learner engagement and motivation. Traditionally deficit based, increased efforts to reconceptualise this arose from an ‘appreciation of Aboriginal health as a core component of professionalism’ and ‘a critical initial step in shaping the enculturation of medical students into their profession’.6,9,11 The Australian Medical Council mandates clinical placements in Aboriginal health settings, along with curricula for medical school students and specialist medical college trainees to ‘develop a substantive understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, history and cultures in Australia’.15 Others have argued that Aboriginal health curricula cannot solely consist of lectures and factual knowledge, and that immersed cultural training may see more meaningful impacts by influencing social justice beliefs and empathy.16 Delbridge et al argue that curriculum approaches to Aboriginal health benefit from co-creation and reflexivity, and recommend practitioners approach curriculum creation and development with consideration of the ways past experiences impact on personal perspectives and professional practice, as well as the way Aboriginal and Western knowledge systems intersect.17 This aligns with the approach of The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, which has committed to the provision of training that equips GPs to be culturally safe and reflective, along with opportunities for continued professional development within Aboriginal health.18 However, this presents significant challenges for many GP supervisors. Translation of policy into practice is problematic without meaningful commitment to decolonised approaches across learning spaces, and supervised GP placements are a keystone learning space in general practice.

It is important that medical professionals are challenged to develop their reflective and empathic selves throughout their medical training.19 However, entrenched program approaches that emphasise core science knowledge can devalue the humanities approach essential for engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and understanding their perspectives regarding health and wellbeing.4,9 In addition:

… praxis in decolonisation requires a paradigm shift away from ‘helping’ those who continue to be marginalised towards actively addressing the powerful institutions that create and sustain oppressive structures to begin with.20

It requires broad attitudinal change that reflects an antiracist approach. Hartland and Larkai argue that decolonised approaches are those that:

… examine and restructure (curricula) that were designed within a colonial mindset, which centralises the White, Eurocentric male’s narrative above all others.21

Decolonised approaches allow us to reflect on how race is presented in our teaching. Arising out of a critical examination of the teaching–learning nexus, antiracism acknowledges the pervasiveness of racism in its existence across multiple levels and asks us to make an active choice to counteract and challenge it, including within medical education.7,21,22

Student placements in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled healthcare services have been shown to shift students’ perceptions, clinical decision making and assumptions, and to help students realise the value of holistic approaches to care, as well as providing practical knowledge to complement the didactic curricula.11,23 Medical students and registrar-level trainees also benefit from having their assumptions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people challenged, seeing a strengths-based approach to care and witnessing the practical application of cultural safety with patient-centred care.6 Boutin-Foster advocates that ‘role modelling is maximized when desired behaviours are observed by learners, imitated and adopted as life-long practices’.24 Approaches that teach values and beliefs around patient-centeredness and social justice advocacy are more successful if they create core competencies to address these with a faculty trained to effectively deliver the teaching in this area.16 Training of faculty is pertinent, and specific Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health learning and teaching units and delivery by experts, in particular Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, is essential for quality teaching. However, this has its own challenges: GPs practice across a vast array of locations and settings nationally. Capturing the essence of expert teaching by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health educators, and maintaining consistency of engagement and content, presents difficulties for GP supervisors.

There continue to be questions regarding the ability for perception changes and discussions to be facilitated in other settings.7,23 Settings that are not Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled healthcare services may result in an unsafe learning environment (Box 1). Regardless of the setting, clinical supervisors are key in promoting social justice and antiracist approaches.23 There are frameworks that can help when discussing controversial topics in medical education. These promote critical self-reflection and value deep discussion and exploration of beliefs around a topic in a non-judgemental way. They are effective in helping educators engage students.24,25 However, educators need skills to teach reflective content and to engage learners in antiracist content, and previous studies have indicated that GP educators lack confidence in delivering this.26

|

Box 1. Case study 1: Experience of a GP trainee

|

|

X is a GP registrar, undertaking their first year of community-based training. Their supervisor has invited them to observe an excisional biopsy with one of the supervisor’s patients. The patient, the supervisor, the registrar and the practice nurse are in attendance. As the biopsy proceeds, the registrar stands towards the back of the procedure room and the supervisor discusses the steps while also engaging in small talk with the patient. The patient raises the recent media coverage regarding changing the date for Australia Day away from January 26. The supervisor offers little opinion on the topic but actively listens.

The patient expresses several derogatory beliefs such as ‘I have a friend who was part of the Stolen Generation who said that being taken away was the best thing that ever happened to them’ and ‘They [Aboriginal people] all get free cars from the government and ruin them after a couple of months’.

The supervisor nods but does not interrupt.

The practice nurse offers that ‘I think Aboriginal people can be quite misunderstood at times, and there are many factors that can contribute to challenges for them in society’.

The registrar feels alienated in this setting. The registrar does not feel comfortable giving a viewpoint or identifying that they are finding the conversation uncomfortable. In fact, the registrar thanks the patient for allowing them to observe.

The supervisor does not offer a debrief about the consultation.

|

|

Questions to consider when analysing or discussing this case

What racism can you recognise in this scenario?

Is there an advocate or ally in this situation?

If you were a bystander, what action could you take to improve the scenario?

|

Decolonisation in education settings seeks to critique practice through counteracting stereotypes in learning material, challenging students to consider racial bias in their clinical thinking and reflecting on the attitudes and behaviours that students are exposed to in a biased curriculum.21 In support of GP supervisors, and others who are interested, Table 1 outlines antiracist approaches that may be useful for the supervisor and in structured teaching sessions, as well as for continued professional development. We have also provided two case studies (Box 1,2). The scenarios will be familiar to GP supervisors and educators, and help illustrate challenging situations, potential responses and work towards a critical analysis of the interactions.

| Table 1. Antiracism in general practice medical education: conversation prompts and starters14,17,24,27,28 |

Personal approaches

- Self-education: IndigenousX, Racism No Way (https://racismnoway.com.au/), Indigenous Health MedTalk podcast

- Engaging in the space: consider joining

- Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) Network

- RACGP Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health faculty

- Australian Indigenous Doctors Association

- Challenging situations when they occur and taking bystander action

- Questioning actions and attitudes

- Presenting alternative narratives and breaking down biases

- Seeking and discussing narratives that challenge colonial structures

- Speaking up: not being implicit with silence

- Showing solidarity

- Non-confrontational responses

|

Collegial approaches

- Bystander action towards colleagues: questioning actions and attitudes

- ‘Why do you think that?’

- ‘Can you provide any evidence that proves that belief?’

- ‘I find that surprising, I have had a very different experience.’

- ‘Is that something you think about all Aboriginal people or is it just this particular situation?’

- Applied advocacy

- Speaking up: not being implicit with silence

- Showing solidarity

- Calling attention to racism in institutional policies (practice, faculty, community, college)

- Attending local cultural and community events

- Auditing your practice for cultural safety and investing in cultural safety training for all practice staff

|

Supervisor approaches

- Providing education to trainees and patients through role modelling

- Delivering specific teaching sessions on self-reflection and attitudes, implicit bias and the impact of racism on patient care (Figure 1 outlines points of racism in healthcare that could be used as a discussion aid)

- ‘Tell me what you understand about cultural safety.’

- ‘Do you know about the key primary health initiatives for Aboriginal people?’ (eg Close the Gap co-payment prescriptions, Aboriginal Health Assessments)

- ‘Please present a patient case where cultural factors played a role in the outcome. What biases did you bring to the consultation? How could the practice/consultation change to make the patient experience better?’

- Bystander actions in the clinical space (eg nurse comments in Case Study 1 [Box 1])

|

Curriculum approaches

General practice curriculum and supervision should adopt an integrated decolonised approach to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health education, including the support of:

- supervisor training (train the trainer)

- reflexivity training (of supervisor and trainee), including writing skills

- facilitated discussion workshops, with trainees and supervisors

- required assessment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health education for registrars and continuing professional development programs

|

|

Box 2. Case study 2: Supervisor–trainee interaction

|

|

At a full practice meeting, the practice manager discusses the promotion and logistics of completing an Aboriginal Health Assessment (Item 715). Several staff members ask questions and the GP trainee expresses that:

I would not feel comfortable offering a health assessment because most of the time I don’t know if someone is Aboriginal. I don’t want to ask and offend anyone. It all seems like extra unnecessary work.

The group discussion diverts, with little acknowledgement of this comment, and the meeting later comes to a close.

The trainee’s supervisor asks to talk to the trainee after the meeting. The supervisor discusses the practice’s processes of identifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in the clinic. The supervisor asks the registrar about their past experiences in terms of clinical placements specifically related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health or cultural safety training received throughout their medical education to date. The supervisor advises that the next teaching session they have planned will start their conversations about cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, discussions that will continue over the placement.

|

|

Questions to consider when analysing or discussing this case

What racism can you recognise in this scenario?

Is there an advocate or ally in this situation?

If you were a bystander, what action could you take to improve the scenario?

What would be a useful approach to address the registrar’s comments if you were the supervisor?

|

Conclusion

Both trainee and supervisor will benefit from decolonised and antiracist approaches to elevate engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthcare and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Supervisors play a pivotal role, helping lay the foundation for lifelong learning that values decolonised approaches and attitudes towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Supervisors must be supported to deliver this complex curriculum that promotes reflection and reflexivity. Meaningful engagement is antiracist engagement and benefits Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities by enhancing cultural safety in clinical spaces. Here, we have provided a starting point for those unfamiliar or ill at ease with concepts of antiracist and decolonisation of education.

Key points

- The influence of supervisors and meaningful curriculum approaches will improve GP trainees’ application of cultural safety principles for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- Role modelling in a supervisor relationship can influence attitudes and beliefs, and promote decolonised approaches.

- Meaningful engagement is antiracist engagement and benefits Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities by enhancing cultural safety in clinical spaces.

Further resources

Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural awareness in general practice activity.