Case

Robert, aged 59 years, is receiving nivolumab as adjuvant therapy every four weeks for one year to reduce his risk of recurrence after resection of a high-risk melanoma. After a few months, he experiences a subacute exertional dyspnoea, which he believes to be due to weight gain. Subsequently, he develops a dry cough and tests negative for COVID-19. At a routine appointment with his general practitioner (GP), Robert mentions these symptoms and his GP requests a chest X-ray and blood tests, which are unremarkable. His GP then organises a computed tomography scan of the chest, which demonstrates mild bilateral patchy infiltrates. Robert’s GP notifies his medical oncologist, who arranges for Robert to commence oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day and regular reviews through the oncology unit’s symptom and urgent care clinic. Fortunately, Robert’s symptoms quickly improve over 48 hours and the prednisolone is weaned over a month. Nivolumab is ceased, and Robert undergoes surveillance.

Introduction

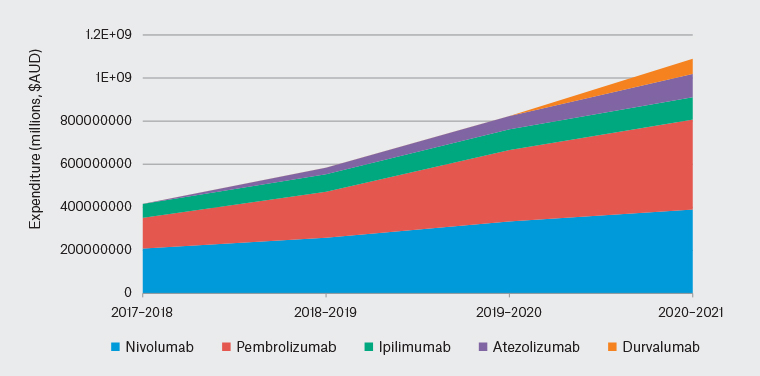

In the past decade, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have emerged as a therapeutic option for cancers with historically poor prognoses or limited response to chemotherapy. ICIs have become a standard of care for the treatment of several cancers. One notable example is metastatic melanoma, where patients receiving combination immunotherapy are experiencing prolonged remissions with a median overall survival of 72 months.1 This increasing use is reflected in the rapid rise of ICI drug-related Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) cost in the four-year reporting period from 2017 to 2021 (Figure 1).2–5 With the increasing use of ICIs, general practitioners (GPs) play a key role in the early identification of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), especially in regional or rural settings.

Figure 1. Australian Government expenditure on immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) immunotherapy agents has increased by more than 2.5-fold in the last four-year reporting period, reflecting the increasing use of these agents. From 2017 to 2018, the reported government expenditure for cancer immunotherapy agents was approximately $415 million, which more than doubled by 2020–21 to more than $1 billion.

What is ICI immunotherapy?

Although immunotherapeutic agents are widely used, this article focuses on ICI immunotherapy used in cancer treatment. ICIs are intravenous therapies, administered once every two to six weeks, used to enhance the immune system’s ability to target cancer cells. Current immunotherapy agents fall into two main classes. The first class of agents targets programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) expressed primarily on immune cells (eg nivolumab, pembrolizumab and cemiplimab) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expressed on tumour cells (eg durvalumab, atezolizumab and avelumab). The second class targets cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4; eg ipilimumab and tremelimumab).6

PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 are known as immune ‘checkpoints’ because they provide inhibitory signals that act as a physiological brake on the cytotoxic functions of T-cells.7,8 Cancer cells can upregulate PD-L1 and/or co-opt these inhibitory pathways to evade immune-mediated cancer cell killing. The goal of ICI immunotherapy is to restore an effector immune response and induce tumour regression.

Unlike other systemic cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapies, the efficacy of immunotherapy can be durable, lasting well beyond the cessation of drug administration.1,9,10

What are irAEs?

Toxicities occur because of increased and indiscriminate immune activation, which causes autoimmune phenomena that can affect any organ or tissue. These are referred to as irAEs.

Anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies have overlapping but distinct irAE spectra, with the risk of adverse events multiplying where combination therapy is used (Table 1).

| Table 1. Frequency of immune-related adverse events |

| |

Frequency (%) |

| |

CTLA-4 blockade (eg ipilimumab)28–30 |

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade (eg pembrolizumab/nivolumab)9,11,28,31 |

Combination therapy (ipilimumab and nivolumab)9,32 |

| Any grade irAEs |

60–87 |

30–74 |

96 |

| CTCAE Grade 3 or 4 irAEs |

23–43 |

10–21 |

55–59 |

| Treatment-related deaths |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

The severity grading of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) is as per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).16 Grade 3 or 4 irAEs refer to severe or potentially life-threatening toxicities requiring intervention and hospitalisation.

CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1. |

Most irAEs are mild and occur within six months of commencing treatment.11 However, irAEs can also be delayed in onset, occurring after several months on prolonged treatment or even after the cessation of treatment.12

In patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases, ICIs are generally well tolerated in those with well-controlled conditions, although they may be contraindicated in those with severe or poorly controlled conditions. There is a risk of exacerbating the pre-existing condition or, less commonly, developing new autoimmune phenomena.13–15

Of importance, the use of live vaccines while on ICIs is generally contraindicated and should be discussed with the treating oncologist if necessary.

Assessment and management of irAEs

Given the wide range of presentations and severity of irAEs, it is important to consider the possibility of irAEs in all patients with an exposure to ICIs, and review by the treating oncology centre is often required. The evaluation and management of irAEs regularly involves specialised immunosuppression and cross-speciality referral, and can have implications for cancer management. This section highlights the general principles of management and provides an overview of common irAEs and important differentials for presenting complaints (Table 2).

| Table 2. An approach to common presentations of immune-related adverse events |

| Presenting symptoms |

Common and/or significant irAE differential diagnoses |

Workup and assessment |

| Fatigue |

- Fatigue associated with immunotherapy

- Consider endocrinopathies: hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, hypoadrenalism, low testosterone/oestrogen, hyperglycaemia

|

- Cortisol, ACTH, TFTs, testosterone, oestradiol, GH, LH, FSH

- Blood sugar and ketone levels

|

| Itch with or without rash |

- Large spectrum from itch without rash to widespread blistering or ulcerating conditions such as SJS/TEN

|

- Consider punch biopsy of the rash

|

| Diarrhoea |

- Immune related diarrhoea and/or colitis

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Thyroiditis

- Type 1 diabetes

|

- Faeces MCS, fat and elastase

- Cortisol, ACTH, TFTs

- Blood sugar and ketone levels

|

| Nausea/vomiting |

- Hepatitis

- Hypophysitis/adrenalitis

- Gastritis/oesophagitis (especially if reflux symptoms are also present)

|

- LFTs

- Cortisol, ACTH, TFTs

- Consideration for upper GI endoscopy would be made if symptoms persist despite PPI therapy

|

| Fever |

|

- Septic screen

- LFTs

- Faecal MCS if diarrhoea

|

| Shortness of breath |

- Pneumonitis

- Myocarditis (often associated with arrhythmias and chest pain)

- Myasthenia gravis (consider if other neurological signs and symptoms)

|

- Degree of hypoxia and fluid assessment

- CT pulmonary angiogram (often performed to exclude pulmonary embolus)

- Cardiac troponin and CK levels

- ECG

- If diagnostic uncertainty, consider bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage, as well as endomyocardial biopsy

|

| Musculoskeletal symptoms |

- Immune-related inflammatory arthritides (eg rheumatoid arthritis)

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Myositis

|

- ESR, CRP, rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP antibodies, ANA

- CK

|

| Neurological symptoms |

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Inflammatory peripheral neuropathies

- Myasthenia-like syndromes

- Encephalitis

- Myositis

|

- Urgent assessment and hospitalisation generally recommended if neurological symptoms are present because these events can be rapidly progressive

- Nerve conduction studies/electromyogram

- MRI of the brain and spine

- CK

|

| Headache |

- Hypophysitis

- Encephalitis or meningitis

|

- Cortisol, ACTH and TFTs

- If other features of encephalitis or meningitis are present, urgent hospitalisation is recommended where brain MRI and lumbar puncture are performed to reach a diagnosis

|

| ACTH, adrenocorticotrophin; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; CCP, cyclic citrinullated peptide; CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GH, growth hormone; GI, gastrointestinal; irAEs, immune-related adverse events; LFTs, liver function tests; LH, luteinising hormone; MCS, microscopy, culture and sensitivity; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; TFTs, thyroid function tests. |

The severity of irAEs is standardised using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) grading system,16 which addresses both symptom severity and objective criteria (Table 3). irAEs have specific categorisations and recommendations for management based on guidelines, for example, by the European Society of Medical Oncology and the American Society of Clinical Oncology.17,18

| Table 3. General approach to the grading and management of immune-related adverse events based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system16,18,19 |

| Grade |

Severity |

Management |

Immunotherapy |

| 1 |

Asymptomatic or mild |

Corticosteroid therapy not usually required

Symptomatic management |

Generally continued |

| 2 |

Moderate: limitations to activities of daily living |

Oral corticosteroid therapy required |

Withheld until resolution or improvement to Grade 1 |

| 3 |

Severe: hospital admission may be required |

High-dose corticosteroid therapy, often intravenous |

Discontinued, rechallenge considered in rare circumstances |

| 4 |

Life-threatening: urgent intervention and possible ICU admission required |

High-dose intravenous corticosteroid therapy |

Permanently discontinued |

| ICU, intensive care unit. |

In general, irAEs that warrant management require initial corticosteroid therapy.19 There are limited data for the management of steroid-refractory cases. However, these events usually require additional immunomodulatory agents and consultation with other speciality services.19 In addition, as for all patients who require prolonged and/or high-dose steroid exposure, there is often an associated increased pill and healthcare burden, which may need to be monitored and managed by the patient’s GP.

Major irAEs

This section provides an overview of several common and significant irAEs, which are summarised in Table 4.

| Table 4. Summary of prevalent and/or significant immune-related adverse events, an approach to assessment, red flags that require clinical urgency and management principles16 |

| Adverse event |

Frequency |

Assessment |

Red flags |

Management principles |

| Skin toxicity |

- Common (30–40%)

- Associated with all ICI immunotherapy classes

|

- Tempo of onset and progression

- Degree of body surface area involved

- Degree of symptoms

- Varied morphology: most commonly presents with a maculopapular rash

|

- Bullae or blister formation

- Desquamation

- Mucosal involvement

- Rapid progression

- Associated hepatitis

- Involved body surface area >30%

|

- If mild, symptomatic management with antihistamines, topical corticosteroids and emollients will usually be sufficient

|

| Diarrhoea/colitis |

- Common (diarrhoea 20–45%; colitis 3–15%)

- Predominantly associated with CTLA-4-targeting agents (eg ipilimumab)

|

- Exclude infectious causes and pancreatic insufficiency

- Endoscopy may appear normal

|

- Increase of seven or more in stool frequency over baseline (CTCAE criteria for Grade 3 diarrhoea usually requiring hospitalisation)

- Fever

- Blood or mucous in the stools

- Abdominal pain

- Fluid loss leading to clinical dehydration, AKI and/or electrolyte derangement

|

- Systemic corticosteroids are often required

- Steroid-refractory cases may require infliximab or vedolizumab with gastroenterology input

|

| Hepatitis |

- Common (5–30%)

- Predominantly associated with PD-1- or PD-L1-targeting agents (eg pembrolizumab)

|

- Exclude other causes

- CTCAE criteria grade this toxicity by the magnitude of derangement above the ULN or baseline value

- For derangements in ALT and AST levels:

- Grade 1 toxicity are values less than threefold above the ULN or baseline value

- Grade 2 toxicity are values three- to fivefold above the ULN or baseline value

- Grade 3 toxicity are values fivefold to 20-fold above the ULN or baseline value

- Grade 4 toxicity are values >20-fold above the ULN or baseline value

|

- Associated bilirubin derangement

- Derangements that are Grade 3 and above will usually require hospitalisation

|

- If Grade 1, may be able to continue treatment and monitor

- Grade 2 and above toxicities require systemic corticosteroids

- Steroid-refractory cases may require mycophenolate with hepatology input

|

| Thyroiditis |

- Common (5–13%)

- Predominantly associated with PD-1- or PD-L1-targeting agents

|

- Degree of symptoms and impact on ADL

|

- Signs and symptoms of severe thyrotoxicosis or thyroid storm

|

- Steroid treatment to reverse or mitigate symptoms is usually not required

- May require symptomatic management of the thyroiditis phase

- Lifelong thyroid hormone replacement when hypothyroidism established

|

| Hypophysitis |

- Uncommon (1-6%)

- Predominantly associated with CTLA-4-targeting agents

|

- Degree of symptoms and impact on ADL

- Complete pituitary hormone panel (ACTH, early morning cortisol, TSH, free T4, LH, FSH, GH, prolactin)

- Pituitary MRI

|

- Signs and symptoms of adrenal crisis

|

- Lifelong cortisol replacement therapy

- Adrenal insufficiency sick day plan and education

|

| Pneumonitis |

|

- Degree of hypoxia and symptoms

- CT scan can be helpful in excluding pneumonitis

- Non-specific radiographic features, including ground glass opacities, a cryptogenic organising pneumonia-like appearance and interstitial pneumonia pattern

|

- Hypoxia

- Symptomatic and/or impaired ADL

|

- Requires frequent and early reviews following commencement of steroid treatment

- Expect improvement after 2–3 days of starting steroid treatment

- Infliximab, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil or IVIG are other immune-modulatory agents considered in severe cases that do not improve clinically after 2–3 days

- ICIs are permanently discontinued if a Grade 4 event occurs, and usually after a Grade 3 event

|

| ACTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone; ADL, activities of daily living; AKI, acute kidney injury; CT, computed tomography; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GH, growth hormone; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LH, luteinising hormone; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyrotropin-stimulating hormone; ULN, upper limit of normal. |

Skin toxicity

The presentation of immunotherapy-induced dermatitis can vary and includes eczematous, acneiform and psoriasiform rashes, although the non-specific maculopapular rash is most common.20 Approximately 30–40% of patients treated with immunotherapy will develop a rash.20,21 Rarely, severe cases resembling Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis can occur, requiring urgent hospitalisation. For mild skin rash and itch, management includes topical moisturisers, topical steroid creams and oral antihistamines.

Diarrhoea/colitis

Diarrhoea is one of the most frequent irAEs observed, and can range from self-limiting diarrhoea to life-threatening colitis requiring prolonged hospitalisation. Enterocolitis can occur with all ICIs, but is more commonly associated with ipilimumab, where 11% of patients experience colitis and 34% experience diarrhoea.10 Red flag symptoms include an increase of seven or more in stool frequency over baseline, fever, blood or mucous in the stools and abdominal pain. Evaluation includes the exclusion of infectious causes. Apparently normal distal endoscopy findings do not exclude intestinal inflammation, because enteritis is also possible.22 Pancreatic insufficiency is also a differential in such cases and may be investigated with faecal elastase, faecal fat or fasting glucose studies.23

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is a common irAE that occurs in approximately 30% of people treated with combination immunotherapy and is often detected incidentally on routine blood tests.19.21 Transaminase levels greater than fivefold the upper limit of normal, and/or raised bilirubin levels, may require hospitalisation for intravenous immunosuppressive therapy. Steroid-refractory hepatitis can occur, requiring consideration of a liver biopsy to differentiate between irAE hepatitis and other causes, including cancer progression.24

Thyroiditis

Immunotherapy-induced thyroiditis is a common irAE that can result in permanent hypothyroidism and commonly follows an often asymptomatic initial thyroiditis phase followed by a prolonged or permanent hypothyroid phase. The incidence immunotherapy-induced thyroiditis is approximately 7% with monotherapy and 13% with combination immunotherapy.17 Once hypothyroidism is established, thyroxine replacement is usually required.

Hypophysitis

Hypophysitis is predominantly associated with CTLA-4 blockade, with an incidence of approximately 3% with monotherapy and 6% with combination therapy.25 Presenting symptoms include headache, nausea, postural hypotension and dizziness, as well as electrolyte abnormalities (hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia) and adrenal crisis. Diagnostic work-up includes complete hormone panel assessment and pituitary magnetic resonance imaging. Management is with long-term hormone replacement therapy.26

In general, endocrine irAEs are exceptions to the general principles of irAE management. These toxicities are usually allowed to take their course, without the use of corticosteroid therapy to mitigate the degree of toxicity, although symptomatic treatment may be required. They are often permanent, but manageable with hormone replacement.

Pneumonitis

Pneumonitis is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening irAE that requires a high degree of suspicion for patients presenting with dyspnoea or cough. The spectrum of clinical presentation can range from asymptomatic to progressive respiratory failure. The frequency of pneumonitis is approximately 3% with monotherapy and 10% with combination therapy.18 The radiographic features of pneumonitis are non-specific, mimicking infectious or inflammatory causes, often resulting in diagnostic uncertainty. Concerning signs and symptoms include hypoxia or exertional desaturation, decreased exercise tolerance and/or limitation to activities of daily living. A CT scan of the lungs is recommended in making the diagnosis of pneumonitis and can confidently exclude pneumonitis if pulmonary infiltrates are absent.27

Take-home message for patients

Because irAEs can often escalate quickly, our practice is to counsel patients on the importance of early reporting of any new or changing symptoms in order to mitigate the severity of these adverse events. We also counsel that although ICIs may offer a durable response, there are potential permanent and fatal risks, which is important for informed consent, particularly in the curative setting. Finally, although rare, the risks of irAEs persist despite prolonged or cessation of treatment.

Conclusion

A high degree of clinical suspicion for irAEs is required in all patients who are currently receiving or have previously received ICI immunotherapy. irAEs can present with mild and non-specific symptoms, often resulting in delays to identification and management that can be fatal or lead to chronic morbidity. The management of irAEs should be conducted by following the available guidelines and algorithms, and will often require consultation with a patient’s treating oncology team.

Key points

- ICI immunotherapy is increasingly used to improve the outcomes of cancer patients in both the adjuvant and metastatic treatment settings.

- ICI immunotherapy is associated with a wide spectrum of adverse events that may affect any organ or tissue in the body and can occur even after the cessation of treatment.

- irAEs are distinct from classical chemotherapy-associated side effects and can present with mild and non-specific symptoms, resulting in delays to identification and management.

- A high degree of suspicion for irAEs is critical for patients who are receiving or have received ICI immunotherapy in order to mitigate the severity of these toxicities.

- Consultation with the patient’s treating oncology team is recommended if patients present with suspected or confirmed irAEs.