Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the full extent of the crisis in general practice, which has emerged as nothing more than the tip of the iceberg of a health system in crisis.

Objective

This article introduces the systems and complexity thinking that frame the problems affecting general practice and the systemic challenges inherent in redesigning it.

Discussion

The authors show how embedded general practice is in the overall complex adaptive organisation of the health system. They allude to some of the key concerns that need to be dissolved in its redesign to achieve an effective, efficient, equitable and sustainable general practice system within a redesigned overall health system to achieve the best possible desired health experiences for patients.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the full extent of the crisis in general practice and the wider healthcare system.1 The crisis of the system emerged as nothing more than the tip of the iceberg of a health system in crisis. Re-establishing the system requires systems and complexity thinking approaches, and the unequivocal acknowledgement that such problems cannot be fixed one bit at a time.2 These insights informed the systemic bottom-up redesign of the community-engaged primary care systems developed by the Indigenous people in Alaska (NUKA health system).3

This article introduces systems and complexity thinking and its implication for the design of seamlessly integrated health systems. It highlights some of the key systemic challenges affecting the general practice system and offers some pragmatic suggestions that general practice organisations can adopt to shape the system’s emergent redesign.

What do we mean by systems and complexity thinking?

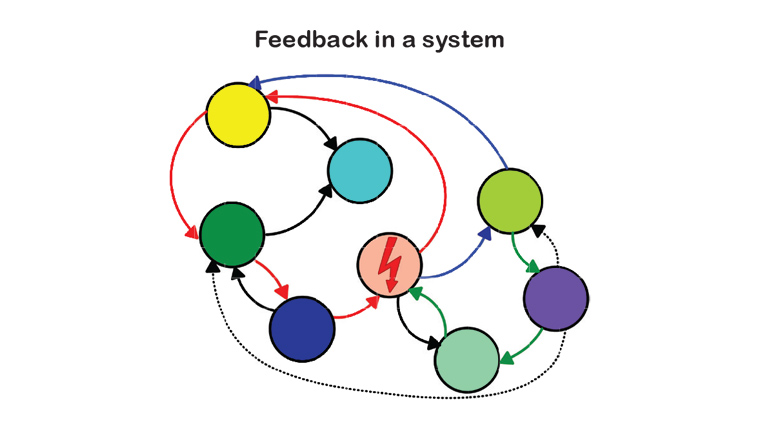

Systems are nested in systems which are nested in systems and so forth. To understand systems, one has to embrace Alexander von Humboldt’s insight ‘that everything is connected to everything else, and if one wants to fully understand a phenomenon [or system], one also has to understand its context [the system within the system]’.4 Hence, to fully appreciate the nature of a system one has to simultaneously understand its structure and interdependencies. Importantly, one has to realise that a change in one element (called agent) of a system will impact the structural relationships and dynamics among all its agents (meaning interconnectedness and interdependence), which, in turn, results in feedback. Feedback is the key driver of systems and explains the emergence of stability or instability of both their structures and their dynamics (Figure 1).

Figure 1. System structure, relationships and dynamics.

Organisations are complex adaptive systems

The principles of systems and complexity thinking also apply to organisations; however, organisations have additional features and are socially constructed systems whose function depends on four key principles:5,6

- For an organisation to function in a seamlessly integrated horizontal and vertical fashion, it needs a clearly defined purpose that succinctly states the reason why it exists.

- An organisation has to determine a set of no more than half a dozen specific goals – defining what it wants to achieve for the time being.

- An organisation has to define its core values, defining why it is doing what

it is doing.

- Together, these principles provide the foundation to jointly establish an organisation’s three to five ‘simple (or operating) rules’ – providing the foundation for how it interacts internally and externally with one another and external stakeholders.2

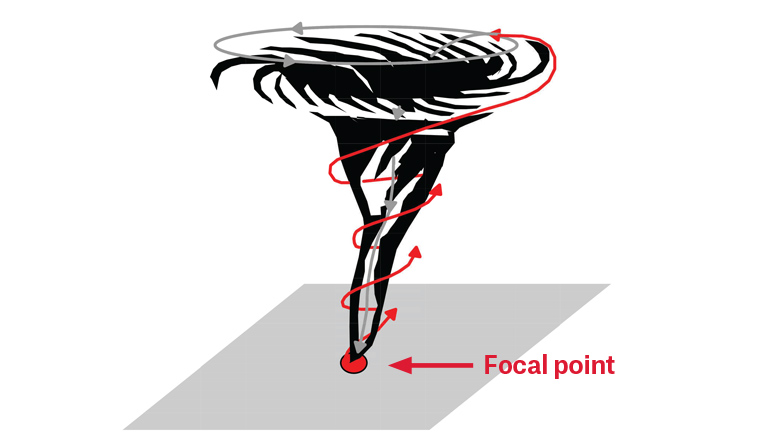

A vortex is a useful illustrative metaphor to represent a complex adaptive horizontally and vertically integrated organisation. A vortex requires a focal point to emerge from the bottom up and, in rising up, it also creates a top-down flow – the two processes (or mechanisms of information flow within an organisation) are required to sustain itself (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Organisations – metaphorically – are structured and dynamically function like a vortex. This means organisations can only form – bottom up – if they have a focus (or known purpose). To maintain themselves as a seamlessly integrated system requires everyone’s work to be aligned to its focus. It is the leadership’s responsibility – top down – to provide the necessary information required for people at lower levels to do the necessary work, and lower levels have the responsibility to provide – bottom up – feedback so that the organisation can adapt its activities to achieve the goals that arise from its purpose.

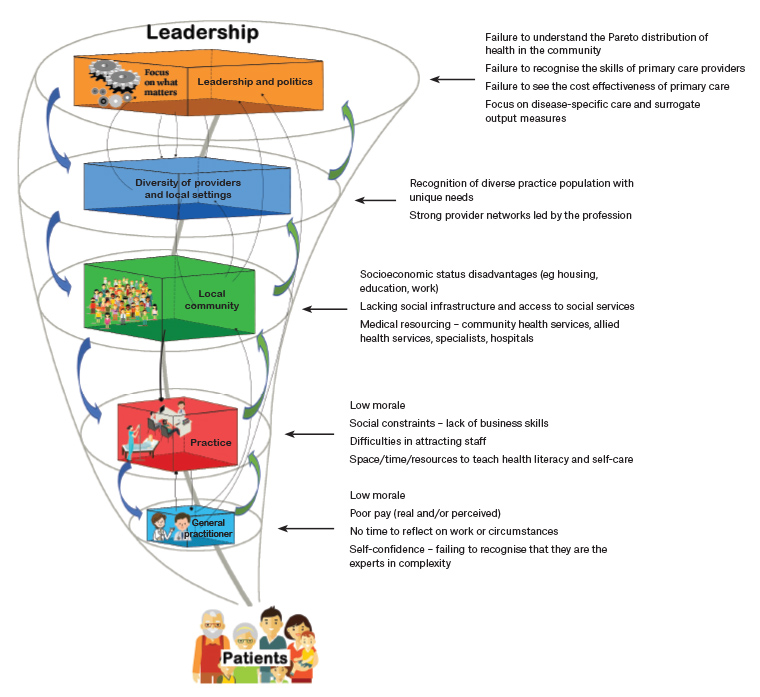

Organisations have functional layers; while each layer must do a particular job, everyone has to do their job according to the overall purpose of the system. Figure 3 shows the layered structure and principal interdependencies of a complex adaptive ‘general practice system’ through the vortex metaphor.

Figure 3. The ‘general practice system’ – current key issues impacting the realisation of its purpose – helping people to achieve their best possible/desired health experiences. Click here to enlarge.

Core challenges to the general practice system at each organisational level

All organisations are perfectly designed to get the results they get!7 Thus, analysing the behaviour of our current health system allows us to describe and understand the particular concerns impacting the general practice system at its various organisational levels (Figure 3). Importantly, while concerns might appear specific to a particular level, they are nothing more than key contributors to the system’s overall dysfunctions. These concerns can only be addressed successfully if they are understood in their context, and if a proposed solution will address the inherent related structural and interdependent issues – everything is connected to everything else. Improving part of a system is only helpful if it simultaneously improves the system as a whole.8,9 Put more succinctly, rectifying each problem encountered in the system – one by one – is failing to dissolve the problem for good (Box 1 lists a number of recent single-focused attempts).8 In other words, taken in isolation as single problems – the typical approach of politicians and bureaucrats – can result in fragmentation. Fragmentation, in turn, disrupts the system in its entirety, and further perpetuates its dysfunction.

Some key concerns impacting the future of general practice at each organisational level are listed below. However, it is worth noting that this list is not exhaustive.

| Box 1. Examples of failed ‘parts improvement’ |

General practitioner level

- The suggestion to raise rebate levels for only confined geographical areas is unlikely to dissolve the entire workforce maldistribution

- The suggestion to raise financial incentives for confined geographical areas is unlikely to dissolve the systemic dysfunctions leading to a workforce maldistribution

Practice level

- The introduction of practice nurses has failed to improve the financial viability of practices

Community level

- Community-based health services have been introduced without sufficient staffing and have therefore failed to improve access to required care

- The persistent lack of alternative accommodation continues to force abused patients to return to their abusive home environments

Regional level

- Pilot studies that have successfully addressed local care needs have not received funding beyond the pilot phase

Political level

- GP divisions have engaged local healthcare providers to system-wide collaboration and have improved service delivery, but were abruptly defunded

- The government has offered financial incentives to maintain doctors in rural areas, but this has failed to improve the rural and remote workforce shortage

|

Key concerns at the general practitioner level

- A key concern of the current general practitioner (GP) workforce is exhaustion and low morale, and the real or perceived view of being inappropriately remunerated.10–12

- The medical education process has not supported many GPs’ self-confidence in their knowledge and skills to provide effective care. In addition, much of the current formal continuing professional development (CPD) programs fail to deliver what providers need at the point of care.13

- While GPs experience and successfully manage complexity daily, they fail to see themselves as the experts in complexity, forgetting – as attributed to Chris van Weel – that GPs are experts in treating patients who do not fit the criteria for inclusion in clinical trials.14–17

- Many GPs are frustrated by not having enough time to address the real issues concerning their patients and/or to engage in advocating to improve their patients’ illness-producing environments.18,19

Key concerns at the practice level

- Exhaustion and low morale are a concern affecting every practice member – nurses, allied health professionals and administrative staff.20

- Practices struggle to attract and retain appropriately qualified and motivated staff.10

- Practice sustainability is challenged by physically constrained practice settings, significant financial constraints, workforce and a lack of specific business skills relating to medical practice.21 Currently, 50% of Australian GP practice owners are concerned about the sustainability of their practices.10

Key community level issues

- The local community context is a potent predictor of the morbidity patterns encountered in a particular practice setting. Socioeconomic disadvantage – in the form of poor education, poor housing, insecure and hazardous work/workplaces – is associated with premature onset as well as severity of morbidities that, in turn, impact the workload and demand of all practice members.22

- Socioeconomically disadvantaged communities are also health system disadvantaged communities; they

have poor access to health services

and, often, the available health services are underfunded and understaffed.23,24

Key issues at the regional level

- In broad terms, there is an underappreciation of the diversity and uniqueness of local communities. Local community characteristics determine the configuration of local health services.25 The current lack of adaptability by health service planners impedes the provision of good healthcare, which, in turn, leads to dissatisfaction of health professionals and culminates in patients and communities being harmed. This is well demonstrated by culturally and linguistically diverse communities.26

- Most regions lack strong GP-led provider networks that are necessary for the collaborative effort needed to provide the best possible care in the context of each patient/community. In Australia, the lack of locally adapted networks began as the government moved away from Divisions of General Practice (which, in many cases, morphed towards Divisions of Primary Care) and now uses a more distant centralised Primary Health Care Network model that covers far greater geographic areas with often diverse population needs.27,28

Key issues at the political level

- The political level has a fundamentally poor systems understanding of the true nature of the health system and, in particular, the role of primary care in its function of maintaining the system’s viability as a prerequisite to the health

of a community.

- There is a failure to understand that health and healthcare needs follow a Pareto distribution,29,30 a failure to recognise the skills of primary care providers,31,32 and a failure to appreciate the cost effectiveness of primary care.31,33

- The political level is near blindly focused on diseases, processes and the associated cost of service delivery. They fail to see the interdependencies between people’s perception of health, how primary care is used and delivered, and the impact of primary care resources on overall healthcare costs.34

- Politics is predominantly driven by economic rather than health concerns with a focus on adhering to processes and achieving predetermined outputs, rather than a focus on how best to achieve patient-centred health outcomes. A reliable patient-oriented outcome measure is the answer to a simple question: did the service received enable me to live and cope better with my diseases? In other words, did it improve my health experience?35,36 Contrast this with the political mindset on economics – Dr Michael Wooldridge’s speech as health minister (between 1996 and 2001) to the Australian Medical Association was unequivocal: the aim of health policy is to build the infrastructure for a global health marketplace.37 This position was vehemently opposed as clearly discordant with the medical profession’s obligations to patient care.38

Challenges for general practice organisations

It is a precondition for GPs and their respective professional organisations to understand the systemic nature of the failings of the health system.21 However, they also have to realise which issues they can directly dissolve and thereby prevent from returning in the future. In addition, they must carefully consider which issues require robust advocacy on behalf of patients’ health and care needs.

Education is an example to highlight these differences. GP organisations have limited abilities to shape medical student selection or undergraduate education; however, they have a great opportunity to excite medical students during their GP rotations about the delicate work required to untangle the complexities of a patient’s complaint.39 GP facilitators need to impart their unique generalist approaches to investigating patient complaints and, most importantly, their ‘whole-person/patient’ management approaches in the context of both acute and ongoing health problems, while taking full account of a patient’s ability to manage their health issues within their specific living conditions.40

GP organisations have the greatest educational influence at the time of registrar selection and during their time of training. The challenge here is to select the right practices and formative role model supervisors who are given the required time and remuneration that allows them to teach how to cope and manage the complexities of patients’ illnesses and coexisting diseases.41

General practice organisations’ key responsibility lies in ensuring their members competence and capability to ensure safe, effective and efficient practise. This entails a duty to facilitate – as distinct from mandate – CPD and quality- improvement activities that are context sensitive and context specific to the needs and circumstances of individual GPs.13 The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) developed such a model but did not pursue the required discourse among its members for its adoption.42

CPD – as recently mandated by the Australian Medical Council (AMC) – is an example that highlights the differences between ‘solving a part’ of the system versus ‘dissolving’ or overcoming the loss of practitioners’ capability to practise safely, effectively and efficiently. Changes to the current formulation of the AMC’s CPD requirements are both an opportunity and a risk as colleges seek to understand these requirements and implement a worthwhile CPD program offering to busy GPs.

Effective advocacy must be systemic. Healthcare is an investment, not a cost – and it provides a high return, both in health and economic terms. However, without an appreciation of the complexities of the health and general practice system, the enforced implementation of unsystemic piecemeal change will – predictably – not only be expensive but fail to equitably deliver effective and efficient healthcare to every Australian regardless of postcode.

Conclusion

This article has outlined the systemic nature underlying the failings of the health system in general and within general practice in particular. Success depends on all GP organisations embracing systems and complexity thinking and developing strategies to educate those who are in a position to redesign the system. These people might not as yet have fully understood the value and efficiency of a seamlessly integrated patient and wellbeing-focused primary care system as the foundation to achieve as much ‘the health of people as the health of the economy’.