General practitioners (GPs) can implement strategies, such as harm minimisation and brief interventions, and safely conduct outpatient weaning and withdrawal programs to engage patients in long-term treatment.

Building rapport and the therapeutic alliance is a worthwhile investment, and has been shown to help facilitate behavioural change, improving overall treatment retention.1Behavioural change is supported through a warm manner, collaboration and positive mutual regard.1,2 Conversely, an authoritarian or coercive approach is more likely to result in resistance and a focus on why the patient cannot change. While much of this is intuitive to GPs, the therapeutic alliance can be actively fostered using behavioural change techniques, such as motivational interviewing, whole-person care and trauma-informed care, along with reflection on GPs’ own biases.3

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are associated with comorbidities and poorer social determinants of health. As with other chronic conditions, such as obesity4 where these factors intersect, SUDs are associated with an overlay of shame, societal judgement and stigma. This contributes to SUD treatment delay; for example, the average delay to treatment for alcohol use disorder is approximately 18 years.5 A non-judgemental approach focusing on the patient’s own values and motivations helps to facilitate self-determination and a sense of agency over one’s destiny.6 This is a fundamental human need and is a core component of motivation to change.6

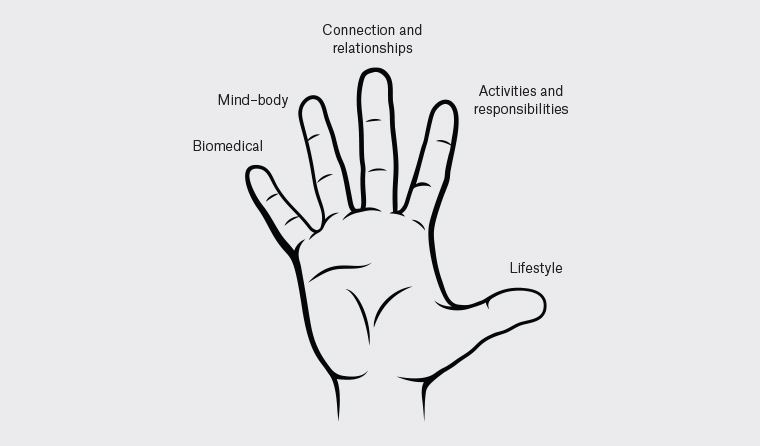

GPs see patients over time, getting to know them, their families and communities, as well as their values, risk factors and protective factors. This builds rapport and enables whole-person care, reinforcing to the patient that their identity is more than their alcohol and other drugs (AOD) use.7 A way of conceptualising this, and building motivation to change, is using the hand model shown in Figure 1.8 GPs can use each of the five domains to help distinguish a person’s intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, both of which can be catalysts for change. Intrinsic motivations, such as wanting to be a better son, daughter, parent or friend, are more likely to result in behavioural change than extrinsic factors, such as meeting financial or court obligations. The five domains can help GPs to build a ‘problem list’ as well as facilitating a strengths-based approach.

Mapping out the five domains helps to clarify and build motivation for change, in order to grow ‘positive reinforcers’ for change as well as protective factors. The five domains are:

- biomedical – physical health and medical treatment

- mind–body – thoughts and emotions, the link between psychological and physical health

- connections and relationships – family, friends, the GP, treating teams, culture, community, spirituality and social groups

- activities and responsibilities – hobbies, childcare, employment, finance, custodial obligations etc

- lifestyle – nutrition, AOD use, smoking, sleep, exercise.

A strengths-based approach and trauma-informed care

A strengths-based approach focuses on a person’s strengths, their protective factors, motivations and values to help empower the individual and create meaningful goals for change.9 This contrasts with a deficit approach that focuses on a person’s problems or failures.9 Trauma-informed care uses a strengths-based approach that seeks to build and maintain relationships with patients who have experienced trauma.10,11 When trying to interpret challenging behaviours, the treating GP can ask themselves the reflective question: ‘what has this person experienced?’.11 ‘Survival’ behaviours can be recognised as having a function that has aided endurance and resilience.9 People who use AOD have higher rates of previous and current trauma.12 For these patients, the power differential between GP and patient can create a triggering environment, or risk mimicking the power dynamic between abuser and victim.10 Being ‘triggered’ is when a person has their ‘threat system’ activated, resulting in the nervous system triggering ‘fight, flight, freeze’.13 Survival behaviours make it difficult for a person to engage in problem solving when their amygdala is running the show. This might present as intoxication, lapse or relapse, somatic symptoms, emotional dysregulation, interpersonal problems, avoidance, re-experiencing, dissociation, memory problems and feelings of shame.14

Being trauma informed assists the GP to understand a patient’s behaviour and their care needs. Disclosure and ‘unpacking trauma’ should be undertaken by a clinician who specialises in the treatment of trauma-related disorders.10 GPs can lay the groundwork for developing healthier coping strategies by enlisting the six principles of trauma-informed care (Table 1). These principles support practitioners to ‘do no harm’ and avoid retraumatising patients.3,15

| Table 1. Principles of trauma-informed care3,15 |

| Safety |

A felt sense of safety in the environment and themselves. Safety provides the foundation for the other five principles |

| Trustworthiness |

Transparency and consistency of behaviour, practice and boundaries over time |

| Choice |

Facilitates agency, shared decision making |

| Collaboration |

The GP walks beside the patient, healing in relationships |

| Empowerment |

Belief in a person’s resilience and aptitude |

| Cultural, historical and gender issues |

Recognises stereotypes, biases and unique care needs |

Discussing alcohol or other drug use

The ‘5As (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange)’ is an evidence-based framework for behavioural change and helps GPs to structure the chronology of their consultation (Table 2).16,17 Linking the patient’s AOD use to their presenting complaint or another comorbidity is a useful way to open the discussion. Always ‘Ask’ if it is okay to discuss AOD use.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) and the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) are the recommended screening tools to determine the level of alcohol consumption or illicit drug use, respectively.18,19 CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye opener) for alcohol screening detects dependent drinkers, but misses most problematic drinkers and is not validated for use in primary care.20

Some patients might engage in ‘high-risk’ AOD use without dependence. For others, an SUD might develop. The authors suggest using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, criteria for diagnosing an SUD, which further categorises SUDs into mild, moderate and severe (Box 1).21 This is in keeping with a chronic disease model approach and is useful when tailoring treatment and developing care plans.

| Box 1. Diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders (SUDs)* |

- Using larger volumes over longer timeframes than intended

- Unable to cut down or reduce use

- Increased time and effort to obtain and recover from substance use

- Cravings for substance use

- Substance use impacting on ability to fulfil important life responsibilities

- Continued substance use causing social and interpersonal impairment

- Social, occupational or recreational activities impacted due to substance use

- Using substances in high-risk situations such as operating a vehicle

- Ongoing substance use despite the known psychological and physical harms

- Tolerance to the substance – needing increased volumes to achieve the same effect, or the same volume diminishing in effect

- Withdrawal symptoms when substance discontinued, or substance continued due to intolerance of withdrawal symptoms

|

Categorisation

- Mild SUD: 2–3 criteria

- Moderate SUD: 4–5 criteria

- Severe SUD: >6 criteria

|

*Based on the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition |

It is worth remembering that some patients might use more than a single drug and have more than one SUD. Using appropriate person-centred language is helpful in moving to a strengths-based approach; for example, using the term ‘alcohol use disorder’ instead of ‘alcoholic’, ‘a person who uses drugs’ rather than ‘addict’, or ‘substance use’ rather than ‘abuse’.22

Examples of tailored management include:

- a person with higher-risk AOD use would benefit from discussions around how to make their AOD use safer and might not need a withdrawal program

- a person with a moderate alcohol use disorder might be appropriate for harm minimisation advice as well as a planned home-based alcohol withdrawal

- a person assessed as having a severe polysubstance use disorder might be more appropriate for a GP-led chronic disease care plan and team care arrangement referral to a specialist AOD service.

Where patients have co-occurring mental health or physical comorbidities, parallel treatment of co-occurring disorders is appropriate – one does not have to treat a condition (eg alcohol use) before treating another (eg depression), or visa versa.10

If there is no urgent medical or physical risk to the patient or others, consider investing in rapport before giving advice. Triage the patient’s agenda, your own agenda and what can be ‘parked’ for future consultations. A well-timed brief intervention of 5–15 minutes might be all a person who is drinking at mild to moderate levels needs to reduce their alcohol intake.23 The feedback, responsibility, advise, menu, empathy and self-efficacy (FRAMES) framework is used to deliver brief interventions and is described in Table 2.24 For further guidance on this, the World Health Organization has a comprehensive brief intervention manual.24 Those using AOD at higher-risk levels (as determined by the above screening tools) and those who have developed an SUD might benefit from extra support, such as referral to a specialist AOD service.

| Table 2. The 5As of behavioural change16,17,24,38 |

| Ask |

Gain consent: Is it okay if I ask you some questions about AOD use?

Consider asking this in the context of the patient’s own agenda – ie linking it to their presenting issue or comorbid history might be an opportunity to incorporate an alcohol assessment |

| Assess |

- What? Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C), Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), K10 questionnaire and stage of change

- When? Opportunistically

- Who? All patients who have agreed to discussing their alcohol use

- Who should not drink? Patients aged <18 years, breastfeeding or pregnant women27

- Increased risk? People who

- are aged ≥65 years, aged ≤24 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or intersex, homeless, in contact with the criminal justice system

- have physical and mental health comorbidities

- are from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- inject drugs.36

|

| Advise |

If your patient is open to discussing their AOD use, you could consider a brief intervention, 5–15 minutes long, using the ‘FRAMES’ framework:19

- Feedback: The patient’s AOD use and individual risks using motivational interviewing. Compare with current recommended guidelines: <10 standard drinks per week, or no AOD during pregnancy and breastfeeding

- Responsibility: For their own choices and maintains a sense of control

- Advise: Action on how to make AOD use safer, which could include reducing or ceasing AOD. Avoid moral judgements

- Menu of options: Create a menu of strategies with the patient to cut down or stop AOD use

- Empathy: A warm approach is best. Avoid confrontation or coercion. Remain curious

- Self-efficacy: Promote hope and confidence in ability.

|

| Assist |

Stages of change (assist to move along the ‘change cycle’; refer to Appendix 1):

- Precontemplation. Not ready for change: raise doubts, encourage harm minimisation

- Contemplation. Ambiguous: explore motivations, promote change talk

- Preparation. Preparing for change: develop strategies, patient led

- Action. Making change: support change

- Maintenance. Relapse prevention, crisis planning

- Relapse. Commend the patient for returning for review and work on the principles of CHIME (Connectedness, Hope and optimism about the future, Identity, Meaning in life and Empowerment to re-engage).

|

| Arrange |

- Follow up with the GP, and pace consultations using chronic disease and mental health care plans as indicated.

- Enlist a team approach (eg an AOD service, psychology, psychiatry, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work).

- Enlist community organisations for longevity and continuity of care (eg Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, case worker/support worker) and consider implementing social prescribing.

- Enlist family support with permission (if appropriate), or use established support networks.

- Consider the patient’s needs from the whole-person care framework.

|

Stages of change

Motivation to change varies across a person’s lifecycle. There are many paths to change. These might be driven by biological, psychological, sociological and spiritual influences.3 Natural change refers to life events, such as studying or having a baby, that lead to behavioural change. The stage of change model and the domains of whole-person care (Figure 1) help to conceptualise a person’s change journey in the context of their lives, and it gives the practitioner something to ‘hang their hat on’ when undertaking motivational interviewing.25,26

Figure 1. Adapted whole-person care domains – Hunter Integrated Pain Service8

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centred conversation structure that assists with behaviour change.27,28 The ‘righting reflex’ is the urge to advise patients on the ‘right’ path to good health.25 Giving advice and proactively treating is a core part of medicine. However, most people resist persuasion when they are ambivalent about change and recall the reasons not to change.27,28

This is termed ‘sustain talk’ and results in discussion around why a person wants to continue using AOD and why they cannot change.27 Unsolicited advice risks entering a power struggle and falling back to an authoritarian or coercive approach, which damages the therapeutic alliance. If you meet resistance from the patient, roll with it, be empathetic and avoid challenging the patient.27,28

At times, rolling with resistance and resisting the righting reflex requires the practitioner to ‘sit on their hands’, especially for patients in the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages of change. Alternative communication techniques are well described in motivational interviewing.27,28 Simple memory aids, such as OARS, can help GPs to build rapport and talk about change: 27

- asking Open-ended questions

- making Affirmations

- using Reflections

- using Summarising statements.

‘Change talk’ is conversation that evokes a person’s desire, ability, reasons and need for change and helps to move a person along the stage of change model.3

Change can be difficult. For those who are not ready, willing or able to change, GPs can keep the patient engaged in health care, roll with resistance and use harm minimisation strategies to signal that the ‘door is open’ for when the patient is ready to change – be it overnight or in several years.27 Refer to Appendix 1 (available online only) for suggested phrases that can be used for patients in each stage of change (these phrases can be used for any substance).

Harm minimisation

Harm minimisation is an approach that accepts that AOD use will occur in some patients who are not currently ready, willing or able to change.29 The aim here is to minimise potential harm and promote ongoing engagement with treatment services. It supports the patient to make safer choices and respects autonomy. GPs can start a conversation by asking if it is ok to discuss their AOD use, about how they use AOD and what they know about safe injecting practices; this will allow you to fill in any knowledge gaps identified (refer to Box 2 for examples).

| Box 2. Harm minimisation advice39 |

- Drink water and eat regularly

- Alternate alcoholic beverages with water

- Limit AOD use to certain times of the day and avoid driving and times of obligation

- Swap drinks to low/no alcohol options

- Set a daily/event limit

- Participate in activities not involving AOD

- Avoid injecting drug use

- Engage in safer injecting such as using ‘fit packs’ that contain alcohol swabs, filters, sterile injecting equipment, and avoid sharing needles

- Daily thiamine for all patients drinking at higher-risk levels

- Access to at-home naloxone for patients at risk of opioid overdose

- Barrier contraception to avoid sexually transmissible infections and long-acting reversible contraception to avoid unplanned pregnancy

- Use safe smoking equipment such as steel, and avoid plastic or aluminium

- Vaccinate against hepatitis A and B, and treat hepatitis C

|

Ceasing or reducing AOD use

The goal of reducing or ceasing AOD use might not be or lead to long-term abstinence.30 Patient safety is the priority of a medically supported withdrawal or weaning regimen. While long-term abstinence might be desirable, many people with an SUD might want to cut down their use, move to ‘controlled’ use or have a brief period of abstinence for a variety of reasons.30 Safe prescribing might involve an agreed medication plan where both patient and GP agendas align, and ensures prescribing is defensible, confirmed (between prescribers, or prescription monitoring) and within professional comfort.31

Strategies to reduce or cease AOD use are most likely to succeed when developed with the patient in the preparation or action stages of change. Being optimistic that recovery is possible aids success. The authors recommend using ‘SMART’ goals, which empower the patient to create goals that are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-based.32 The aim is to help the patient come up with their own strategies.

Withdrawal symptoms are a feature of SUD and result in behavioural, physiological and cognitive changes due to either ceasing or reducing substance use.30 GPs can enquire about withdrawal symptoms by asking the patient what a typical day looks like for them, how soon after waking they need to take AOD and what happens if they have a period of time where they do not use AOD. Withdrawal from AOD can be safely undertaken in the outpatient setting as long as a patient meets certain criteria.30 Seeing a GP for AOD treatment can help a patient feel less stigmatised, be more anonymous and overcome resourcing barriers to care in rural and remote settings.33

A person may be suitable for a home-based withdrawal program if an SUD is mild and:30

- there are no complications

- there is no history of seizures

- there is no comorbidity or concomitant substance use

- there is no risk of suicide

- the patient has a support person and safe/secure accommodation.

Complex withdrawal for moderate to severe SUD or those with comorbidities should be managed in the inpatient setting as withdrawal can be harmful and life threatening. If considering undertaking a home-based withdrawal from AOD, the authors recommend familiarising yourself with Turning Point’s Alcohol and Other Drug Withdrawal Guidelines and contacting your local AOD clinical advisory service to ensure a robust withdrawal plan that is safe for the patient and GP.30

Cravings are at their most intense in the early stages of cutting down or ceasing AOD use. ‘Urge surfing’ strategies help patients to ‘ride the wave’ of cravings.34 Strategies to cope with cravings include delaying AOD use, distracting, deep breathing, slowly drinking a glass of water, positive self-talk, relaxation and imagery.35

The maintenance phase is when a patient is in recovery. A whole-person care approach and relapse planning are techniques used to keep the patient engaged in recovery.35,36 Review the ‘positive reinforcers’ of your patient’s new behaviour or identity. Review potential ‘triggers’, high-risk scenarios and develop a crisis plan for lapse and relapse.36,37 The authors suggest using the CHIME (Connectedness, Hope and optimism about the future, Identity, Meaning in life and Empowerment) acronym, to frame conversations in the maintenance and relapse phases (refer to Table 2 and Appendix 1).35,37

Identifying barriers to treatment

If a patient appears ready but does not follow through with their action plan, use Figure 1 to review the patient’s barriers to change – are they ready, willing and able?27 What is hindering their readiness, willingness or ability? How realistic are the strategies you have made with the patient to carry out in their everyday life? When there is a lapse or relapse, commend the patient for returning, re-engage in the change cycle and engage the CHIME principles to reinforce or renew the patient’s motivations for change.36,38

Conclusion

Empowering patients to change AOD-related behaviours can be challenging and take time. A person’s identity is much more than their AOD use and this forms the cornerstone of motivational interviewing. A respectful, non-judgemental approach that is trauma informed fosters rapport, directly counteracts stigma and improves treatment retention. Evoking the patient’s motivations for change by using a holistic approach that targets the intervention to the patient’s stage of change helps to further overcome barriers to care. By building the therapeutic alliance and taking a strengths-based approach, GPs can create safe spaces that act as an ‘open door’ for AOD treatment across a person’s lifecycle.

Key points

- Rapport and the therapeutic alliance are central to AOD treatment.

- Motivational interviewing, whole-person care and trauma-informed care are essential skills for AOD treatment.

- The 5As (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange) framework is a useful tool for GPs to support patients to change their behaviour.

- The stages of change model assists GPs to target their motivational interviewing and intervention.

- GP-led weaning and withdrawal can assist patients to cease AOD use and relapse prevention strategies can maintain these changes.