Case

A woman aged 69 years was referred to dermatology outpatients with a 12-month history of periodic episodes of blisters affecting the extensor surfaces of her hands, feet and elbows. Blisters were described as painless, non-pruritic, usually containing blood and lasting approximately four days before crusting and healing. She was otherwise well with no systemic symptoms.

She took no regular medications and was a non-smoker.

On examination, there were resolving vesicles and bullae on the extensor aspect of the elbows, right index finger and the dorsum of the left foot (sites of friction). Milia were present at the sites of healed lesions (Figures 1, 2). No further lesions were noted on complete examination of the skin and mucosal surfaces.

Figure 1. Vesicles and secondary milia noted on both hands

Figure 2. Close-up of vesicles and secondary milia noted on the right hand

Question 1

What are the potential differential diagnoses for this presentation?

Answer 1

Primary vesiculobullous lesions might be the result of autoimmune blistering disorders, bullous drug reactions, genetic blistering disorders, infection and traumatic insult to the skin.1 Factors that help to differentiate such aetiologies include the distribution of lesions, involvement of mucous membranes and whether blisters are flaccid, tense or present as erosions (Table 1).2

| Table 1. Differentiating features of vesiculobullous disorders |

| Disorder |

Aetiology |

Distribution |

Mucosal involvement |

Clinical features |

| Epidermolysis bullous acquisita |

Autoimmune |

Generalised

- Areas prone to trauma and friction (ie hands)

|

Variable |

- Tense bullae and erosions

- Scarring and milia are common

|

| Bullous pemphigoid |

Autoimmune |

Generalised

- Trunk, extremities and flexures commonly affected

|

Uncommon – involvement in up to 30% of cases |

- Tense bullae

- Urticarial plaques

- Scarring uncommon

|

| Dermatitis herpetiformis |

Autoimmune |

Generalised

- Extensor extremities, scalp and buttocks commonly affected

|

Uncommon |

- Tense blisters or just excoriations

as it is very itchy

- Grouped vesicles with intense pruritus

|

| Porphyria cutanea tarda |

Genetic or acquired

|

Photodistributed

- Dorsum of hands and forearms commonly affected

|

Uncommon |

- Non-inflammatory vesicles and bullae

- Most commonly on dorsum of hands and forearms

|

| Pseudoporphyria |

Acquired

- Ultraviolet radiation

- Drug reaction

|

Photodistributed

- Dorsum of hands commonly affected

|

Uncommon |

- Non-inflammatory vesicles and bullae

- Most commonly on dorsum of hands and forearms

- No porphyrin metabolic abnormalities

|

| Pemphigus vulgaris |

Autoimmune |

Generalised

- Scalp, face and upper trunk commonly affected

|

Common |

- Flaccid vesicles and erosions

|

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome |

Infection

- Exotoxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus

- Usually seen in children aged <5 years

|

Generalised |

Uncommon |

- Flaccid bullae

- Extensive erythema with desquamation of skin

|

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis |

Drug reaction |

Generalised |

Prominent |

- Flaccid bullae with skin sloughing

- Prodromal period of flu-like symptoms

- Commonly result from medication exposure

|

| Fixed drug eruption |

Drug reaction |

Localised

- Lips, face, genitalia and acral sites commonly affected

|

Variable |

- Dusky violaceous patch with haemorrhagic bulla

|

Histopathological factors including the level of blister formation (intraepidermal or subepidermal), mechanism of blister formation (spongiosis, acantholysis, blistering degeneration or epidermolysis) and the type of inflammation (neutrophilic, lymphocytic, eosinophilic, mixed) can guide diagnosis.3 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of intact perilesional skin is also needed.

This patient had blisters involving acral areas and extensor surfaces suggesting a mechanobullous disorder due to trauma or friction in these areas. The differential diagnoses included epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) mechanica, bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.4

Case continued

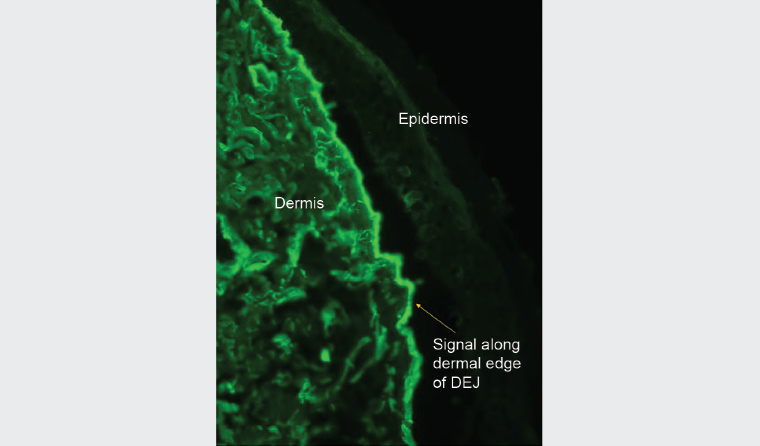

The patient’s referring general practitioner (GP) had already performed biopsies for histology (Figure 3) and DIF, which showed a subepidermal vesicle and moderate linear positivity for C3 at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ) and strong linear positivity for immunoglobulin (Ig) G at the DEJ. Further perilesional skin punch biopsies were taken (Figure 4). One biopsy was submitted for repeat DIF and the other was submitted for salt-split skin testing to differentiate bullous pemphigoid and EBA. The salt-split skin test revealed linear IgG along the dermal side of the split (Figure 5). IgA, IgM and C3 were negative. Coeliac antibodies and anti-skin antibodies were negative; while the serum porphyrins were borderline elevated, the patient did not have porphyria curtanea tarda clinically. Antibodies to type VII collagen (Col7) were not detected in the patient.

Figure 3. A bullae of the right elbow with ink marks representing the site of perilesional punch biopsies

Figure 4. Haematoxylin and eosin staining of an excised lesion. The subepidermal vesicle, which contains sparse neutrophils and lymphocytes, is labelled

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence on salt-split skin testing showing linear immunoglobulin G along the dermal edge of the split

Question 2

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Question 3

What is the natural history of this condition?

Question 4

What is the cause of this condition and how is it treated?

Answer 2

Bullous pemphigoid is more common than EBA and shares subepidermal blistering and deposition of IgG and C3 along the basement membrane. However, the patient did not have the generalised blistering and itchy, urticarial lesions associated with bullous pemphigoid. The infiltrate on light microscopy would usually show conspicuous eosinophils whereas the patient showed sparse neutrophils and lymphocytes.

Bullous lupus should also be considered but the patient had no clinical features for this condition. She did have a high antinuclear antibodies (ANA) titre, with negative anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), and tested positive for extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) and Ro-52 antibody, alongside a low positive Ro-60 antibody screen. The patient had no clinical features of an autoimmune connective tissue disorder but should be monitored in case one develops.

Salt-split skin testing confirmed the clinical impression of EBA showing IgG on the dermal side of the split. In conjunction with salt-split skin findings, light microscopy, clinical features and immunofluorescence, the diagnosis of EBA can be made.5

Answer 3

EBA is an autoimmune condition characterised by tense subepithelial blisters over sites of trauma, typically the hands, elbows, feet and knees. Mucosal regions might also be involved.6

EBA can manifest clinically at any age with a bimodal age peak in the second and seventh decades.7 Males and females are affected equally and EBA can occur in all ethnicities.7 Other autoimmune conditions, such as Crohn’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus, can be associated.6 There are several subsets of EBA that include the likes of classical forms and non-classical forms. Non-classical forms include bullous pemphigoid (BP)-EBA, mucous membrane-EBA, IgA-EBA and Brunsting-Perry-EBA. The most common form of EBA is the classical (as demonstrated in this case) and BP-EBA presentations.7

EBA is named for its similarities to milder forms of epidermolysis bullosa – a large group of inherited mechanobullous disorders ranging from mild to extremely severe clinical expression. In its worst form, epidermolysis bullosa results in a large burden of morbidity and greatly shortened lifespan. Epidermolysis bullosa is due to inherited defects of the basement membrane zone resulting in skin fragility, blistering with trauma/friction and, in more severe forms, scarring and loss of function.

Answer 4

EBA is due to a Col7 defect because of IgG autoantibodies directed against the NC1 domain of Col7. Col7 is responsible for anchoring the basement membrane of the epidermis to the dermis. This results in the development of blisters within the hemidesmosomes of the lamina densa, within the basement membrane zone.8 Antibodies to Col7 are detected in up to 60% of EBA patients.9

Basic treatment measures include wound care, avoiding friction and trauma, avoiding sunburn and the application of a potent topical steroid to lesions. First-line systemic treatment agents are oral colchicine or dapsone.7 Other steroid-sparing agents, such as azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and ciclosporin, can be considered subsequently.7 Induction with oral corticosteroids might be required for severe cases. Intravenous Ig and rituximab can be used for treatment-resistant disease.7

Case continued

The patient was not significantly impacted by her blisters and declined systemic treatments. She protects her skin from injury where possible, applies betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% to lesions and is being monitored.

Key points

- A biopsy of a blister edge for histology and a biopsy of perilesional skin for immunofluorescence is crucial in diagnosing immunobullous skin eruptions.

- EBA mechanica should be considered in patients with newly developed blisters in areas that are prone to friction.

- Other immunobullous disorders, bullous lupus, PCT and pseudoporphyria need to be excluded.

- The presence of IgG deposition along the DEJ is seen in bullous pemphigoid and EBA; salt-split skin testing can differentiate these conditions.