Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing for the early detection of prostate cancer has been a contentious topic for several decades. Evidence suggests that PSA testing is unlikely to be suitable as a population-based screening program due to inconsistent information relating to the relative benefits and harms of testing on mortality. A shared informed decision-making consultation between men and their general practitioners (GPs) to discuss the benefits and risks of PSA testing is required. However, such consultations can be challenging due to time constraints and the need for healthcare practitioners to ensure they stay up to date with the most recent evidence.

Poor awareness of prostate cancer in Australian men is also a barrier to communication. Here, we identify local prostate cancer resources available to the general population and healthcare practitioners to support the shared decision-making discussion. This includes regional prostate cancer factsheets developed by the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia (PCFA), which highlights why knowing the local disease burden is particularly important in the management of prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australian men but awareness of the disease is poor.1,2 There is no population screening program for prostate cancer because there is inconsistent evidence on whether PSA testing improves mortality. PSA testing for asymptomatic men therefore relies on the available clinical guidelines and individual GP practices. However, Australian guidelines on PSA testing have conflicting recommendations resulting in significant confusion among GPs and consumers. For men who have been informed of the benefits and harms of a PSA test and decide to undergo PSA testing, the PCFA/ Cancer Council of Australia guidelines provide recommendations on the PSA testing strategy that should be undertaken: that is, to provide regular PSA testing every two years for asymptomatic men between the age of 50 and 69 years.3 The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (Red book), meanwhile, states that screening by PSA testing is ‘not recommended’ and patients who request testing should be informed of the benefits and risks associated with the test.4 This discrepancy has been discussed openly in the media and updates on both sets of guidelines are likely to occur in the near future, as the Federal Government announced funding to update the existing PCFA/Cancer Council PSA testing guidelines.5

The responsibility rests with GPs to convey the necessary information about the risks and benefits of PSA testing. However, this might be easier said than done as GPs are often limited by the consultation time available to convey large amounts of information to patients. Decision aids for PSA testing are designed for this purpose, but there is little evidence to show that this improves the informed shared decision making. Nevertheless, there are local resources available (Table 1) to help enhance patients’ knowledge and facilitate an informed decision on PSA testing.

| Table 1. Examples of local resources providing general information on prostate cancer and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing |

| Organisation |

Year |

Title and resource type |

Primary purpose |

| Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia |

– |

What you need to know about prostate cancer, Downloadable document (pdf) |

General information booklet on prostate cancer for patients and their families and carers |

| Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia |

– |

Should I have PSA test, Downloadable document (pdf) |

General information booklet on PSA testing men diagnosed with cancer |

| National Health and Medical Research Council |

2014 |

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in asymptomatic men, Downloadable document (pdf) |

Information factsheet to support healthcare practitioners to discuss PSA testing with men and their families |

| The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners |

2015 |

Should I have prostate cancer screening?, Downloadable document (pdf) |

Decision aids for PSA testing for men |

| Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia |

2016 |

PSA testing and early management of test-detected prostate cancer. Clinical practice guidelines, Online resource and downloadable document (pdf)3 |

Clinical practice guidelines for PSA testing for healthcare practitioners |

| Healthy Male Andrology Australia |

2018 |

Prostate cancer diagnosis, Downloadable document (pdf) |

General information factsheet on prostate cancer, PSA test and diagnosis for the public |

| Healthy Male Andrology Australia |

2018 |

PSA test, Downloadable document (pdf) |

General information factsheet on PSA test for the public |

| Cancer Council Australia |

2020 |

Understanding prostate cancer, Brief information available as an online resource. Detailed information available as downloadable document (pdf) |

General information booklet on prostate cancer for patients and their families and carers |

| The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners |

2021 |

Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice – early detection of cancers – prostate cancer, Online resource and downloadable document (pdf)4 |

Recommended practice guidelines for PSA testing for general practitioners |

| Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia |

– |

Understanding prostate cancer |

General information on prostate cancer with the aim to raise awareness of the disease |

In March 2021, the PCFA released a suite of factsheets on prostate cancer burden covering 88 regional areas nationwide based on the Statistical Area Level 4 (SA4) boundaries (www.stargate.org.au). The aim was to improve community awareness for prostate cancer with an accessible and consumer-friendly resource. The factsheets provide simplified statistics of regional disease burden relevant to a consumer (eg relating to where a patient lives or the local practice area of a GP). A two-page factsheet of a specific region can be accessed by conducting a postcode search.

There is little evidence on effective resources/interventions to assist GPs in conducting an informed shared discussion. Poor population health literacy/awareness is a significant barrier in clinical decision making and is also associated with poor outcomes. Providing disease burden information in a personalised manner (and shown for local areas) has been reported to be an effective strategy to improve communication and health literacy in patients.6,7 Furthermore, understanding local disease burden is particularly meaningful for prostate cancer where risks and benefits need to be balanced. In rural Australian communities, prostate cancer incidence and mortality were reported to vary by geographical areas (eg 32% higher mortality in rural areas) and sociodemographic status.8,9 It is also the first time where stage of diagnosis information is available for small geographical areas. This information is clinically relevant because of the association between late-stage diagnosis and increased risk of prostate cancer mortality. Overall, the factsheets provide accurate and detailed information about disease burden for both the patients and GPs.

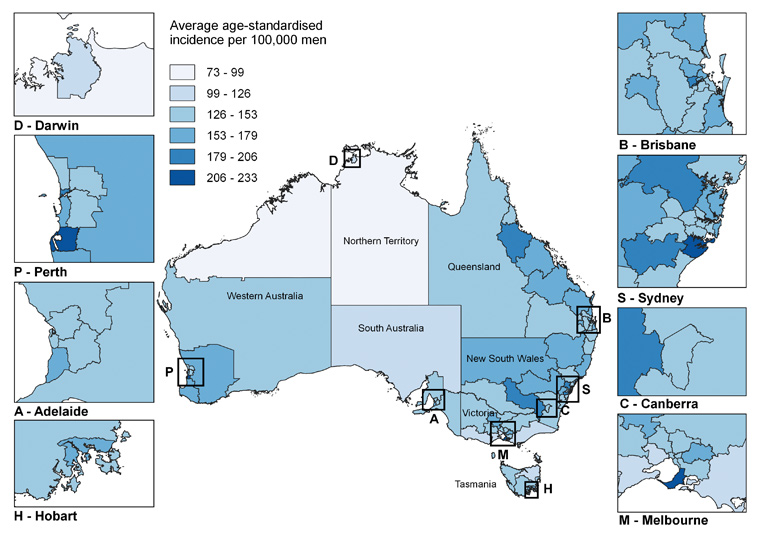

The PCFA factsheets cast a spotlight on some of these geographical disparities in prostate cancer. The average age-standardised prostate cancer incidence rates ranged from 73 to 233 per 100,000 men (Figure 1) and ranged from 17 to 36 per 100,000 men for mortality rates. It is important to note that the variations in incidence are influenced by many factors, including both population risk and factors such as variation in testing and biopsy rates. For example, Sydney/Sutherland (NSW) and Mornington Peninsula (Vic) were among the highest incidence rates in metropolitan regions but were also shown to have the highest prostate biopsy rates for men aged over 40 years within their states.10 Caution is therefore required in the interpretation of the information.

Figure 1. Average age-standardised prostate cancer incidence rate per 100,000 men by Statistical Area Level 4 regions between 2012 and 2016. Click here to enlarge.

The PCFA factsheets were released during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Unpicking any effect of the factsheets on testing behaviour is not possible. As we anticipate clinical practice to recover from the pandemic and allow more face-to-face consultation, we hope that the factsheets can be of more value to GPs during patient consultations. However, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of the factsheets by determining the validity and acceptability of the material and identifying gaps and obtaining feedback. Depending on the availability of data, regular updates and additional data on geographically based variables such a PSA testing rates, including free-to-total PSA tests, accessibility to specialists and multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging, are also likely to be useful and should be considered in the future. Prostate cancer nurses and support groups also have an important role in disseminating information. Coupled with this information on local health service availability and usage, the factsheets can be a useful resource to inform policy decisions and health service planning in local areas.