“It is the child of avarice, the brother of inequity and father of mischief … it has been the ruin of many worthy families the loss of many a man’s honour and the cause of suicide.”

– George Washington, 1783

Gambling is defined as betting something of value on an event of uncertain outcome with the intent of winning something of value1 (eg lotteries, poker machines, casino games, scratch cards, betting on sports/races, keno). Gambling is popular in Australia, with 53% of adults in New South Wales (NSW) gambling at least annually2 and 39% of Australians gambling monthly.3 Gambling costs Australia $4.7 billion per year.4 Australians spend more money per person gambling than any other country and around twice as much as other Western countries.5

Classified as a behavioural addiction in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)6 and a disorder due to addictive behaviours in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision,7 a ‘gambling disorder’ is the result of specific behaviours that are rewarded and reinforced by repetition. Gambling disorders occur in roughly 0.5% of adults8 and are comparable to substance-use disorders.9 The term ‘problem gambling’ is more commonly used in Australia, and refers to a spectrum of mild, moderate to severe problems2 and harms to oneself or others due to gambling.10 It does not require a clinical diagnosis and is based on self-report generally through validated screening tools. Approximately 1% of adults in Australia experience severe problem gambling,3 and 7.2% are at risk of developing problem gambling.11 Problem gambling is characterised by continuous or periodic loss of control over gambling, increased gambling frequency and amounts wagered, preoccupation with and obtaining funds to gamble and continued gambling despite adverse consequences for the individual and/or those around them. Common harms include psychological distress, poor physical health, lack of sleep, stress, financial distress and relationship breakdown.10 Suicide rates among people experiencing problem gambling are 15-fold higher than in the general population.12 More than 96% of those with a gambling disorder have at least one comorbid mental health issue, including depression, anxiety and personality disorders, and are more likely to use nicotine, alcohol and other drugs.13 For each person with problem gambling another six people (eg family, friends) will be adversely affected.14

| Case study: Joan, aged 45 years |

|

You have seen Joan over the years in your surgery.

Joan has obesity, hypertension (treated with ramipril 5 mg) and a history of past risky alcohol use.

On the urging of her partner, Martin, Joan attends today complaining of insomnia and fatigue: ‘Martin wanted me to attend today, really I’m ok, just not sleeping so well, if you can give me a sleeping tablet I can take for a few days, that should sort it.’

As part of your routine assessment you say, ‘Sometimes people turn to drugs, alcohol or gambling as a way of coping. Would you say any of these have negatively affected you or others in your life?’

‘I occasionally have a gamble, it’s not a problem, I can manage it …’

You say, ‘Sometimes gambling can cause people problems, I wonder if you might be worried about your gambling and this might be affecting your sleep and energy levels. Can you tell me more about your gambling?’

Joan replies, ‘Look, I can control it. Martin gives me a hard time and I’ve taken out a couple of loans to manage cash flow, but it’s really ok.’

You say, ‘I understand that Joan, I also know it’s not uncommon for gambling to get out of hand and this can cause people and their families real issues. There are free and confidential resources and services available that can be helpful. Please remember my door is always open and you can come back and talk about this anytime. In the meantime, let’s have a closer look at your physical health.’

|

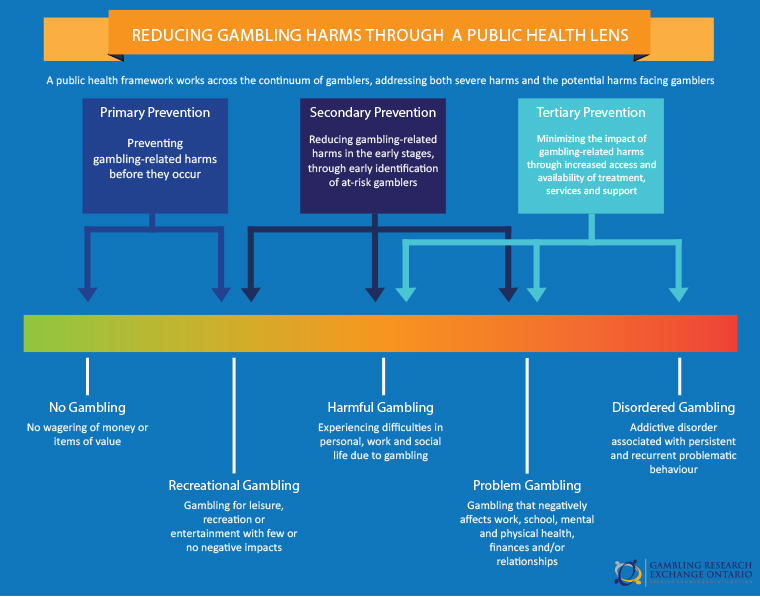

People can cycle in and out of problem gambling15,16 (Figure 1). On average, nine years elapse between experiencing problem gambling and seeking treatment. Problem gambling can also develop suddenly and quickly spiral out of control.16

Online/mobile technologies have made gambling constantly and immediately available, allowing it to become private, easily hidden and impulsive. Digital payments increase spending compared with cash.17 Internet gambling is threefold more likely to cause problems than venue-based gambling.18 COVID-19 accelerated the uptake of online gambling, and individuals already at-risk of problem gambling tended to intensify their online gambling and develop problems despite closed venues.19,20

Figure 1. Spectrum of gambling. Click here to enlarge

Figure 1. Spectrum of gambling. Click here to enlarge

Reproduced with the permission of Gambling Research Exchange Ontario.29 Note, this infographic was created in 2017 and is inclusive of the evidence available at that time.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to enhance general practitioner (GP) awareness of problem gambling, its impact, general practice presentations, screening, effective treatment and referral options.

How problem gambling presents in general practice

Problem gambling may present as physical/mental health difficulties and may not be identified until significant harm has occurred. It may present in the following ways:10

- relationship difficulties

- stress and related health problems (eg insomnia, poor nutrition or overeating, cardiovascular issues, hypertension, headache/migraine, gastrointestinal symptoms)

- poor self-care

- emotional or psychological distress, including depression and anxiety

- suicidal ideation

- financial and legal problems

- problems with work or study, including lower productivity or job loss

- reduced engagement in activities previously enjoyed

- criminal activity, including fraud, theft or money borrowed from

family/friends.

Dopamine agonist medication has a rare adverse effect of increasing the risk of problem gambling.

Problem gambling can affect anyone, regardless of background. However, it is more common among:

- women experiencing loneliness, grief or interpersonal trauma

- younger men reporting stress, anxiety and financial problems

- middle-aged men with substance use issues

- the unemployed and employees of gambling venues

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- people living in poverty

- culturally and linguistically diverse groups

- individuals with comorbid mental health and drug and alcohol problems.3

Why people do not seek help

Less than 10% of people with problem gambling seek specific professional support,21,22 and most only at crisis point. This may be due to shame and stigma, lack of awareness or denial of the problem, limited knowledge of treatment options or feeling hopeless about changing their gambling. People may not see problem gambling as a health issue and not connect the physical and mental health symptoms they are experiencing with gambling. Nonetheless, GPs are the most preferred source for help with problem gambling.23

Sometimes people, like Joan in the case study, are not ready to change their gambling. Ambivalence is normal. This may be the first time problem gambling has been considered or discussed with another person. As GPs, we can express concern and flag that effective treatment is available, we can assist and will follow up. Motivational interviewing techniques can promote understanding and resolve ambivalence, facilitating change.24

How to ask about problem gambling

We can normalise asking about gambling by raising it as part of a lifestyle assessment, when taking a medical history or as part of a mental health assessment (Box 1).

| Box 1. How to ask about gambling |

|

‘Do you like to gamble?’

‘Sometimes people turn to drugs, alcohol, or gambling as a way of coping. Would you say any of these have negatively affected you or your family?’

‘Do you do anything that concerns or negatively affects you, such as gambling?’

Open-ended questions may assist more comprehensive assessment

- Experience of harm

- Is gambling affecting you or anyone you care about negatively?

- Is your gambling interfering with anything else in your life?

- What would be different if you were gambling less?

- Loss of control

- Is your gambling getting out of hand?

- Have you ever thought about or tried to stop?

- Preoccupation

- Do you ever experience urges to gamble?

- Does gambling interfere with your ability to enjoy and engage with other activities?

- Progression

- How has your gambling changed over time?

- Is gambling as much fun as it was?

|

Stigma and shame limit help seeking. Using non-stigmatising person-centred language (eg ‘problem gambling/harms’ rather than ‘problem gambler’ or ‘gambling addict’) can assist disclosure. Labelling the person as a ‘gambler’ or ‘addict’ defines the person by the problem, implying change is impossible.

Displaying posters and pamphlets in your waiting room will signal that it is part of our role as GPs to discuss gambling and that it may be asked about during consultations.

There are a number of validated screening tools to help people talk about their gambling.

- Lie/bet test:25 This consists of two questions based on the DSM-5. One or more ‘yes’ answers suggests that help is needed.

- Have you ever bet more than you intended to?

- Have you lied to others to conceal the extent of your gambling?

- Brief Bio-Social Gambling Screen:26 This consists of three questions based on the DSM-5. One or more ‘yes’ answers suggests that help is needed.

- During the past 12 months, have you become restless, irritable or anxious when trying to stop/cut down on gambling?

- During the past 12 months, have you tried to keep your family or friends from knowing how much you gambled?

- During the past 12 months, did you have such financial trouble as a result of your gambling that you had to get help with living expenses from family, friends, welfare?

- Problem Gambling Severity Index (https://www.gamblinghelponline.org.au/take-a-step-forward/self-assessment/problem-gambling-severity-index-pgsi#/?_k=uv7n6a): This nine-question screening tool explores behaviour and harms. Responses are classified as no-risk, low-risk, moderate-risk or probable problem gambling.

Managing problem gambling

Psychological treatment has a strong evidence base and is effective for problem gambling.27 Pharmacological options have little evidence of benefit.28 Gambling-specific treatment services are freely available in every Australian state and territory and offer confidential, online and in-person treatment options without referral for people and their family members affected by gambling. There are many resources available for professionals (Box 2).

| Box 2. Where to seek further information and referral options |

There are expert and free referral options around Australia for people with problem gambling.

- National

- Gambling Help Online: offers online chat and email counselling, peer-support discussion forums, SMS/text support, gambling assessments, gambling calculator, recovery stories, self-help modules, practical ways to help those with problem gambling and resources in languages other than English

- Each Australian state and territory funds free, confidential, in-person treatment. For locations see state-specific gambling help websites, which also offer resources for self-help and to help professionals support people and their families impacted by gambling

Several online self-directed mobile app-based interventions have been developed:

Self-exclusion allows people to sign an agreement that they will not enter a gambling venue (or use an online gambling account) and the venue/operator will block them from entry. People can also set temporary time-outs and set spend limits with online wagering operators.

Several banks offer the ability for individuals to block their debit/credit cards/accounts from gambling transactions. Clients typically need to access this function through their online bank account or by contacting their bank. |

As GPs we can help our patients:

- understand that gambling-related concerns are common and can happen to anyone

- understand what motivates them to start a gambling session, what leads them to repeat the same cycle and how gambling adversely affects their life

- identify and challenge misinformed beliefs about gambling

- identify behavioural strategies to avoid gambling, reduce gambling and manage urges to gamble

- identify and manage high-risk situations for gambling

- manage the impacts of gambling on their life (eg relationships, daily functioning)

- change habits and patterns in contexts where they are more likely to experience an urge to gamble (eg gambling venues).

Support for people affected by a loved one’s gambling

Support for family members impacted by gambling is important. Gambling services can provide:

- information about gambling and gambling treatment

- guidance on how to start a conversation about gambling with loved ones and encourage them to seek professional help

- ways to support a loved one who is experiencing gambling harms

- information about relationship difficulties (eg trust, communication, boundaries)

- information for people to help them protect themselves against the impacts of their loved one’s gambling (eg financial, legal)

- mental health support (eg stress, anxiety, depression).

Where relevant, a collaborative shared-care approach between GPs and specialist gambling services may be useful for people with problem gambling and their families. People may benefit from referrals to multiple support services, including community mental health, relationship counselling, drug and alcohol services, financial counselling and legal aid.

Conclusion

Problem gambling is an important health issue causing harm to people who gamble, their families and communities. As GPs, we see people impacted by problem gambling in our general practices, but they may need prompting to volunteer this information. We can have real impact by asking about gambling. Although not everyone who gambles has a problem, early intervention can allow people to maintain low-risk gambling. For those who have developed problems, psychological treatment with experienced gambling counsellors is highly effective. As GPs we play an important role by asking and identifying, providing advice and support and helping to motivate change, then referring our patients and their families to address problem gambling. By understanding and recognising the symptoms, impacts and mechanisms of problem gambling, we can effectively assist our patients and increase the use of appropriate interventions, leading to better health and wellbeing outcomes.

Key points

- For every 20 adults in general practice, one person may have problem gambling.

- Gambling is often not the presenting complaint, so screening is essential to identify harms.

- Just ask, or use validated screening tools to help people talk about their gambling.

- Taking a non-judgmental collaborative approach and using resources is helpful.

- Gambling-specific psychological treatments are free, effective and available across Australia.

Competing interests: : HHKW has no connections with the tobacco, alcohol, or gaming industry. HHKW has received funding for consultancies, untied educational grants and/or expert advisory panels from Indivior, Lundbeck, Seqirus, Mundipharma, Camurus and Pfizer; payment for involvement in the rollout of Safe Script NSW; is a member of the expert and clinician panels on monitored medicines as part of roll out of Safescript NSW; and is Chair of the RACGP Specific Interest Group in Addiction. SMG has worked on projects that have received funding and in-kind support through her institution from the Australian Research Council, NSW Liquor and Gaming, NSW Office of Responsible Gambling, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, National Association for Gambling Studies, Responsible Wagering Australia, Australian Communication and Media Authority, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, ClubsNSW, Crown Resorts, and Wymac Gaming Solutions. SMG has received grants or contracts through partnership research with the University of Sydney from Sportsbet, Entain, Aristocrat, Brain and Mind Centre, NSW Office of Responsible Gambling, Cambridge Health Alliance and Wymac Gaming Solutions; consulting fees from KPMG, Coms Systems Limited, Advance Gaming (NZ) Limited, Norths Group and Clubs 4 Fun; payment for an expert witness report for QBE Insurance, Stibbe; and honoraria directly and indirectly for research, presentations and advisory services from Gamble Aware, Behavioral Insights Team (UK), National Council on Problem Gambling (NCPG) Singapore, Star Entertainment, Australian Cricketers Association, Washington State Council, Leagues Clubs Australia, NSW Gambling Regulators, NSW Office of Responsible Gambling, Credit Suisse, Oxford University, ClubsNSW, Centrecare WA, Gambling Research Exchange Ontario, Crown, Community Clubs Victoria, Financial and Consumer Rights Council, Australian Communications and Media Authority, Taylor & Francis, VGW Holdings, Nova Scotia Provincial Lotteries and Casino Corporation, British Columbia Lottery Corporation, Gambling Research Australia, Responsible Gambling Trust, Clayton Utz, Greenslade, Coms Systems Ltd, Advance Gaming NZ Ltd, QBE Insurance, Department of Social Services, RSL & Services Clubs Assn, Communio, Centre of Addiction and Mental Health, North Sydney Leagues Club, Senet Compliance Academy, KPMG, New York Council on Problem Gambling, Clubs 4 Fun, Stibbe B.V., Minter Ellison, and Generation Next. The most up-to-date listing of funders and recent grants is available on her university website: https://www.sydney.edu.au/science/about/our-people/academic-staff/sally-gainsbury.html. SMG is the Editor of International Gambling Studies; a board member and journal editor for the International Society of Addiction; a steering committee member for the Gambling Policy and Research Unit, Behavioural Insights Team, UK, Research Hub and GambleAware UK; and an invited member of the NCPG Singapore International Advisory Panel.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Funding: None

Correspondence to:

hester.wilson@health.nsw.gov.au

Did you know you can now log your CPD with a click of a button?

Create Quick log

References

- Dickerson MG, O’Connor J. Gambling as an addictive behaviour: Impaired control, harm minimisation, treatment and prevention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Search PubMed

- Browne M, Rockloff M, Hing N, Russell A, Boyle CM, Rawat V. NSW gambling survey, 2019. Commissioned by the NSW Responsible Gambling Fund. Sydney: NSW Government, 2020. Available at www.gambleaware.nsw.gov.au/-/media/files/nsw-gambling-survey-2019-report-final-amended-mar-2020.ashx?rev=442dc0a92d954b368f8bdf34525d539b [Accessed 29 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- Armstrong A, Carroll M. Gambling activity in Australia. Findings from wave 15 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. Melbourne: Australian Gambling Research Centre; Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2017. Search PubMed

- Australian Government, The Treasury. Productivity Commission Report into Gambling. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. Available at www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/gambling-2010/report [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- The Data Team. The world’s biggest gamblers. The Economist, 9 February 2017. Available at www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/02/09/the-worlds-biggest-gamblers [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. Fifth edition. Washington, DC: APA Publishing, 2022. Search PubMed

- World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of diseases 11th revision (ICD-11). Geneva: WHO, 2022. Available at https://icd.who.int/en [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- Heinz A, Romanczuk-Seiferth N, Potenza MN. Gambling disorder. Cham: Springer, 2019. Search PubMed

- Wareham JD, Potenza MN. Pathological gambling and substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010;36(5):242–47. doi: 10.3109/00952991003721118. Search PubMed

- Browne M, Langham E, Rawat V, et al. Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. Melbourne, Vic: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, 2016. Available at https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/assessing-gambling-related-harm-in-victoria-a-public-health-perspective-69/ [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Gambling in Australia. Canberra: AIHW, 2021. Available at www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/gambling [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- Livingstone C, Rintoul A. Gambling-related suicidality: Stigma, shame, and neglect. Lancet Public Health 2021;6(1):e4–5. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30257-7. Search PubMed

- Rash CJ, Weinstock J, van Patten R. A review of gambling disorder and substance use disorders. Subst Abuse and Rehabil 2016;7:3–13. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S83460. Search PubMed

- Goodwin BC, Browne M, Rockloff M, Rose J. A typical problem gambler affects six others. Int Gambl Stud 2017;17(2):276–89. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2017.1331252. Search PubMed

- Currie SR, Hodgins DC, Williams RJ, Fiest K. Predicting future harm from gambling over a five-year period in a general population sample: A survival analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03016-x. Search PubMed

- Black DW, Shaw M. The epidemiology of gambling disorder. In: Heinz A, Romanczuk Seiferth N, Potenza M, editors. Gambling disorder. Cham: Springer, 2019; p. 29–48. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-03060-5_3. Search PubMed

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Gambling. Productivity Commission inquiry report. Melbourne: Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2010. Search PubMed

- Gainsbury SM, Russell A, Hing N, Wood R, Lubman DI, Blaszczynski A. The prevalence and determinants of problem gambling in Australia: Assessing the impact of interactive gambling and new technologies. Psychol Addict Behav 2014 28(3):769–79. doi: 10.1037/a0036207. Search PubMed

- Jenkinson R, Sakata K, Khokhar T, Tajin R, Jatkar U. Gambling in Australia during COVID-19. Research summary. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. Search PubMed

- Gainsbury SM, Swanton TB, Burgess MT, Blaszczynski A. Impacts of the COVID-19 shutdown on gambling patterns in Australia: Consideration of problem gambling and psychological distress. J Addict Med 2021;15(6):468–76. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000793. Search PubMed

- Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. Seeking help for gambling problems. Discussion paper. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, 2014. Available at https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/documents/19/seeking-help-for-gambling-problems.pdf [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- Gainsbury S, Hing N, Suhonen N. Professional help-seeking for gambling problems: Awareness, barriers and motivators for treatment. J Gambl Stud 2014;30(2):503–19. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9373-x. Search PubMed

- Håkansson A, Ford M. The general population’s view on where to seek treatment for gambling disorder – a general population survey. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2019;12:1137–46. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S226982. Search PubMed

- Tumbaga L, Ryan L, Macaw E. Motivational interviewing in problem gambling counselling: Application and opportunities. A clinician’s guidebook. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, 2015. Available at www.mdproblemgambling.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/MI-Final-Print-Book-20160122-V1-00.compressed.pdf [Accessed 6 March 2023]. Search PubMed

- Johnson EE, Hamer R, Nora RM, Tan B, Eisenstein N, Engelhart C. The Lie/Bet questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychol Rep 1997;80(1):83–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.1.83. Search PubMed

- Gebauer L, LaBrie R, Shaffer HJ. Optimizing DSM-IV-TR classification accuracy: A brief biosocial screen for detecting current gambling disorders among gamblers in the general household population. Can J Psychiatry 2010;55(2):82–90. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500204. Search PubMed

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. Search PubMed

- Victorri-Vigneau C, Spiers A, Caillet P et al. Opioid antagonists for pharmacological treatment of gambling disorder: Are they relevant? Curr Neuropharmacol 2018;16(10):1418–32. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170718144058. Search PubMed

- Gambling Research Exchange Ontario. Applying a public health perspective to gambling harm. Ontario: Gambling Research Exchange Ontario, 2017. Available at www.greo.ca/en/programs-services/resources/Applying-a-public-health-perspective-to-gambling-harm---October-2017.pdf [Accessed 28 March 2023]. Search PubMed

Download article