Background

Acute cardiac events confer an increased risk of mental health problems, which compromise physical recovery and increase the risk of recurrence and premature mortality.

Objective

This paper provides an overview of the nature, prevalence, predictors and impacts of post-cardiac event mental health problems, and outlines the benefits of mental health screening, effective treatments for mental health problems and the role of general practitioners (GPs) in the identification and management of mental health problems in cardiac patients.

Discussion

Post-event mental health problems are common, yet gaps exist in their identification and management in acute inpatient, cardiac rehabilitation and primary care settings. Effective screening tools and treatment options are available and have been shown to improve not only mental health, but also cardiovascular outcomes. GPs are well placed to contribute to the identification and management of post-event mental health problems provided they are equipped with adequate information about treatment and referral options.

This article is part of a longitudinal series on cardiac conditions.

Mental health problems are common after acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and other cardiac events. Recent estimates indicate that one in three cardiac patients will experience clinically significant anxiety and up to one in four will be depressed after an acute coronary event.1–4 Approximately 15% will be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.5 Heart attack and other cardiac events are also associated with elevated rates of suicide (Box 1).6 As well as being distressing for patients and negatively impacting quality of life, these mental health conditions compromise physical recovery and return to normal functioning.7 Patients with post-event mental health conditions are less likely to take medications as prescribed,8 are less adherent to lifestyle recommendations, including increasing physical activity, dietary change and smoking cessation advice,9,10 are less likely to attend cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs11 and have increased inflammation and altered autonomic function,12 poorer functional capacity13 and an increased risk of recurrent cardiac events and premature mortality.14,15

| Box 1. Common post-acute myocardial infarction mental health conditions |

| Anxiety |

Many patients experience heart-focused hypervigilance, fear of re‑events or disease progression, and death anxiety |

| Depression |

Patients might develop depression involving profound sadness, hopelessness and loss of interest in activities they previously enjoyed |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

The trauma of the event can lead to PTSD resulting in intrusive thoughts, nightmares and flashbacks to the event |

| Increased suicide risk |

The risk of suicidal ideation and completed suicides is elevated after a cardiac event |

The ‘cardiac blues’: Psychological adjustment during early convalescence

Importantly, health professionals need to allow an initial adjustment period before pathologising early post-event emotional reactions. In the first three to four months after the event, almost all patients (up to 80%) will experience a period of psychological adjustment, known as the ‘cardiac blues’. The cardiac blues involves non-clinical psychological symptoms, including emotional, cognitive and behavioural changes (Box 2).16 Although more transient than clinical depression (the ‘cardiac blues’ are defined by their shorter trajectory), they can be challenging for patients, causing emotional dysregulation and mood swings, cognitive changes such as confusion and forgetfulness and uncharacteristic behaviours such as social withdrawal, tearfulness and irritability.16 This period of emotional adjustment often co-occurs with a similar period of physical adjustment and recovery after AMI and cardiac surgery.17

| Box 2. Symptoms of the ‘cardiac blues’ |

| Emotional changes |

Shock, denial, worry, anger, sadness and guilt; worry about recurrence; preoccupation with death |

| Behavioural changes |

Loss of interest in usual activities, withdrawal from others, tearfulness, irritability, sleep problems, changes in appetite, reduced sex drive |

| Cognitive changes |

Confusion, forgetfulness, inability to concentrate, difficulty making decisions, bad dreams and nightmares |

Importantly, the cardiac blues are considered a normal part of cardiac recovery, and have been likened to a bereavement, grief or adjustment response. With time, acknowledgement and support, the cardiac blues should resolve by around three to four months after the event without pharmacological or psychological intervention.18,19 Once resolved, the cardiac blues are not predictive of a poor prognosis or ongoing mental health issues, hence the importance of normalising rather than pathologising these early symptoms.16,17

Persistent anxiety and depression

For some patients, the cardiac blues do not resolve and mental health problems set in, whereas for others, serious mental health symptoms emerge later in the convalescent period, after the four-month mark.20,21 A recent Australian study involving a large sample of over 900 ACS and cardiac surgical patients admitted across four hospitals in metropolitan Melbourne documented the prevalence of anxiety and depression over the first 12 months after the event.1 The rates of anxiety and depression symptoms remained concerningly high, even in later convalescence, with 31% of patients meeting clinical cut-offs for anxiety or depression at the 6- to 12-month mark.1 By this time the mental health symptoms are well entrenched and more resistant to treatment. Moreover, by this point patients have left the supportive environment of their treating hospital, many are no longer attending regular cardiology appointments, opportunities to attend CR programs have passed and family, friends and coworkers expect that things should be ‘back to normal’.

Who is at risk?

We know who is at risk of persistent and severe post-event anxiety and depression (Box 3). Mental health history is a key predictor: people who have had anxiety or depression in the past, prior to their cardiac event, have a fourfold increased risk of experiencing post-event anxiety or depression compared to patients with no mental health history.1,22,23 For those with major depressive disorder, symptoms are highly likely to recur episodically in response to stressful life events, including health crises such as ACS, cardiac surgery or other cardiac diagnosis. Anxiety is often conceptualised as a trait characteristic, again highlighting its likely recurrence in the setting of triggering circumstances.

| Box 3. ‘Red flags’ for anxiety or depression after a cardiac event |

- Mental health history

- Age <55 years

- Socially isolated, lonely, no close confidante or lives alone

- Experiencing financial strain or low socioeconomic status

- Comorbidity, such as diabetes or obesity

- Regularly smokes cigarettes

- Experiencing concurrent bereavement

|

Social isolation and loneliness confer a twofold increased risk of post-event depression, whereas having a strong support network, being partnered and/or cohabitating are protective factors.1,3,22,24 Younger age is also a predictor: patients aged <55 years at the time of their event are twice as likely as their older counterparts to develop post-event anxiety and depression.1,22,25 Financial strain and being of lower socioeconomic status also confer a twofold increased risk of anxiety and depression,1,2,23,24 as do comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity,1,2,23 risk behaviours such as cigarette smoking1,25 and concurrent stresses such as job loss, relationship breakdown or the death of a loved one.1,22 Combined, these risk factors can be considered cumulative: for example, a patient who is aged <55 years, has a mental health history and is unpartnered has an 85% likelihood of having clinically significant anxiety or depression in later convalescence.1

Screening and identification

In light of the high prevalence and prognostic importance of post-event depression, Australian guidelines recommend routine depression assessments at first presentation and at the next follow-up appointment, with a follow-up screen two to three months after the event and subsequent screening on a yearly basis.26 Ideally screening should occur at every opportunity to enable closer monitoring of symptoms. Although the Kessler 10 (K10) is the most commonly used screen in general practice, the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are recommended in Australia as the preferred tools for the identification of anxiety and depression, respectively, in cardiac patients.26 Short versions, namely the GAD-2 and the PHQ-2, can be used as brief screeners before progressing to the longer versions. All GAD and PHQ versions are available at www.phqscreeners.com.

But who should screen for and manage mental health problems in cardiac patients? Although initial opportunities are available during the patient’s hospitalisation, a recent international scoping review highlighted many barriers to integrating mental health screening into the acute inpatient setting.27 Outpatient CR programs such as those offered in Australia provide an ideal opportunity for systematic screening for anxiety and depression, and a recent Australian study identified reasonably high rates of screening in the CR setting on both entry to and exit from CR.28 However, CR attendance in Australia is suboptimal, with recent data showing only 30% of eligible patients are referred to CR and, of those, only 28% attend,29 compromising the efficacy of screening efforts in this setting. Indeed, a Danish study demonstrated that patients most in need of mental health support, such as younger patients, those with comorbidities, smokers, those of lower socioeconomic status and those who are less physically active, are least likely to be screened in CR, underscoring the risk of bias and inequities introduced in this setting.30 The low rate of CR attendance, particularly among the most at-risk patients, highlights the important role of GPs in supporting cardiac patients’ post-event recovery.

Role of GPs in screening and management

General practice provides the ideal setting for the identification and foundational management of mental health problems, together with appropriate referral for additional psychological or psychiatric support if required. A recent Australian study demonstrated that cardiologists regard GPs as being primarily responsible for identifying and managing depression in cardiac patients.31 Importantly, GPs are the most commonly consulted health professionals in Australia, even for mental health issues.32 Almost all (95%) Australians with a chronic condition consulted a GP during 2022.32

Managing the cardiac blues

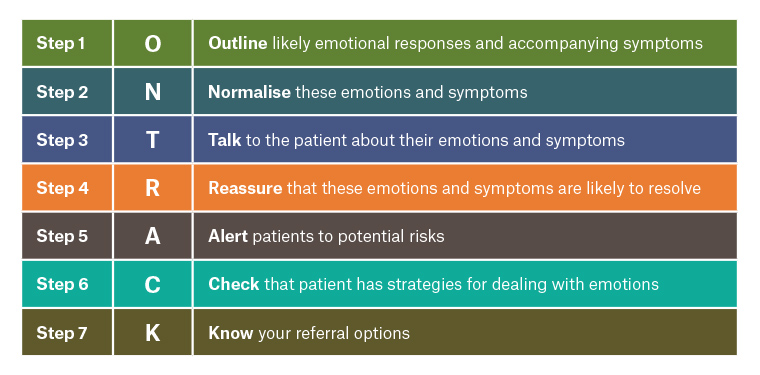

For patients in the early post-event period, the cardiac blues can be managed by GPs using a simple seven-step process involving outlining to the patient the symptoms and likelihood of experiencing the cardiac blues, normalising these symptoms, asking the patient about their experiences, providing reassurance while also alerting the patient to the potential risks, checking that the patient has strategies for managing their emotions and making a referral for mental health treatment if required.16,18,19 This easy reference ONTRACK (Outline, Normalise, Talk, Reassure, Alert, Check, Know) approach (Figure 1) has been shown to improve health professionals’ confidence in managing the cardiac blues in clinical practice.18,19

Figure 1. Seven steps to managing the ‘cardiac blues’: The ONTRACK approach.

Managing anxiety and depression

The recommended mental health treatments for cardiac patients include CR attendance, lifestyle recommendations, psychological interventions, pharmacological treatments and collaborative care.26 Some of these can be prescribed within the general practice setting, whereas others require a GP referral, preferably on a mental health treatment plan to minimise out-of-pocket expenses for the patient.

Encouraging CR attendance

CR programs provide critical post-cardiac event support to improve self-management of physiological, behavioural and psychological risk factors. There is Level IA evidence that CR attendance decreases morbidity, improves quality of life and survival and results in broader social and economic benefits.33–35 GPs are well placed to encourage their patients to attend CR as soon as possible after hospital discharge, provided they are aware of available CR services, understand the benefits and are able to convey these benefits to their patients.36 With patients commonly reporting lack of car access and distance from the CR venue as their major barriers to CR attendance,37 GPs also have an important role in referring patients to home-based telehealth CR programs and community-based exercise programs of patients’ choice.38

Physical activity prescription

Physical activity is highly efficacious for treating anxiety and depression in patients with heart disease. In a 2021 meta-analysis involving 771 coronary heart disease patients across 11 randomised clinical studies, physical activity and exercise were shown to significantly improve anxiety and depression symptoms.39 Indeed, there is some evidence that regular physical activity is equivalent to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment in improving depression in patients with coronary heart disease.40 Physical activity has also been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in depressed ACS patients, with improved outcomes due to enhanced parasympathetic tone and decreased inflammation.41

Dietary change advice

Post-event mental health problems are associated with poorer dietary intake, including a low intake of vegetables, fruit and fibre and a high intake of saturated fats.24 Consistently, recent studies suggest that adopting a Mediterranean diet comprising largely plant-based foods, with a moderate intake of fish and a minimal intake of red meat and sugary foods, is associated with better mental health outcomes after AMI.42

Referral for psychological support

Common psychological interventions for cardiac patients include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), problem-solving therapy, patient-centred therapy, motivational interviewing, stress management, acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness and meta-cognitive therapy.43 CBT is graded as Class 1 Level A of evidence and is recommended in Australian clinical cardiac guidelines for mental health management.26 Five systematic reviews have demonstrated that psychological or psychosocial interventions result in improved mental health symptoms, specifically reduced anxiety, depression and stress,44–48 with one review also demonstrating a significant reduction in cardiac mortality.44 Our own CBT-based Beating Heart Problems program has been shown to improve physiological and behavioural cardiovascular risk profiles,49 reduce anxiety and depression severity50 and, for younger patients, improve survival.51 It is important for GPs to know their referral options, including locally based psychologists and psychiatrists, and other relevant services. The Cardiac Counselling Clinic of the Australian Centre for Heart Health offers evidence-based cardiac-specific counselling and support through its team of trained registered psychologists. To find out more go to: www.australianhearthealth.org.au/cardiac-counselling-clinic.

Prescription of pharmacological treatments

SSRIs are effective treatments for anxiety and depression in cardiac patients. A 2021 Cochrane systematic review including data from 37 trials demonstrated that SSRIs resulted in significant depression remission and improved symptoms in ACS patients.48 A 2021 meta-analysis demonstrated that SSRI use was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent AMI in depressed ACS patients.52 Sertraline, citalopram, fluoxetine and mirtazapine in particular have been shown to be safe and effective for treating depression in cardiac patients.26,53 However, certain SSRIs, such as fluvoxamine, fluoxetine and paroxetine, can interact with antihypertensive medications, such as metoprolol and captopril, and should therefore be used with caution.53 Benzodiazepines can be prescribed for the treatment of both acute53 and chronic54 anxiety in cardiac patients, and have been associated with a reduced risk of heart failure hospitalisation and cardiac mortality in patients with a history of AMI.53 Tricyclic antidepressants can worsen cardiovascular outcomes and should be avoided in cardiac patients.26 Importantly, there is some evidence that adjunct pharmacological treatment enhances the effectiveness of psychological interventions for post-event anxiety and depression.44

Collaborative care

Collaborative care models involve the GP, cardiologist or cardiac surgeon, the CR team of allied health professionals, a psychologist and/or psychiatrist and a social worker, if required, working collaboratively to coordinate pharmacological and psychological care for cardiac patients with comorbid mental health problems. Collaborative care models have been shown to be effective for the identification and management of mental health problems, resulting in improved quality of life, improved referrals, reduced depressive symptoms and increased rates of treatment of mental health disorders.55

Conclusion

GPs have a crucial role to play in identifying and managing both transient and persistent mental health challenges commonly experienced by Australians who have had an acute coronary event, including ACS, AMI, cardiac surgery and other cardiac diagnoses. These events are distressing and often traumatic for many patients, commonly triggering new or recurrent anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress. GPs are well placed to contribute to: mental health screening in cardiac patients; the acknowledgement and management of the ‘cardiac blues’ within general practice; exercise and medication prescription, when appropriate; the referral of patients for psychological or psychiatric assessment and treatment as required; and the referral of all cardiac patients to CR programs.