Background

The National Health and Medical Research Council’s National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research and updated Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research provide guidance for primary care researchers.

Objective

This paper describes a step-by-step approach to ethics applications for research projects in primary care for new or inexperienced researchers, or those new to primary care research.

Discussion

Domains that may enhance ethics applications include increased consumer involvement; comprehensive literature reviews; evidence of researcher training in ethical research and clinical trials; the use of online platforms for participant information, consent processes and surveys; and consideration of the risks of genomic research or research in subpopulations. This paper discusses steps required when preparing ethics applications to ensure the community, clinicians and researchers are protected.

This article is part of a longitudinal series on research.

Research is part of our search for knowledge and understanding.1 Ethics processes are essential for protecting research participants and the community.2,3 Driven by increasing community concern regarding consumer protection, as well as by greater uptake of new technologies, these processes have increased and become more formalised.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to ensure that quality research is designed to be conducted in an ethical manner, in our search for knowledge.

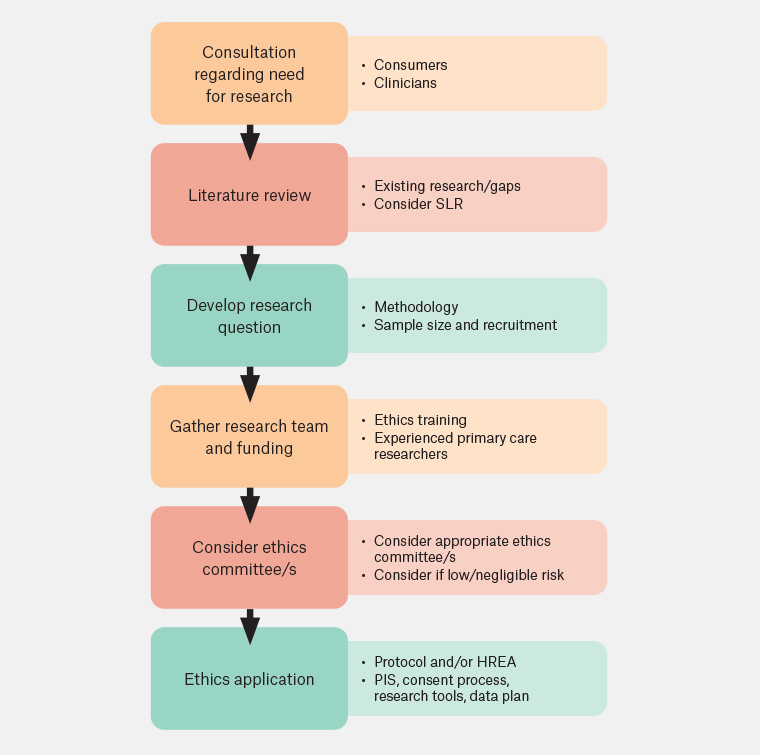

The objective of the paper is to outline the process of preparing an ethics application for a primary care research project; it is designed for novice or early career researchers. The process of preparing a research protocol and an ethics committee application form is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Ethics application process.

HREA, human research ethics application; PIS, participant information statement;

SLR, systematic literature review.

Research ethics: Weighing the potential benefits and harms from the instigation of a project

For research to be considered ethical, the potential benefits must outweigh the potential risks and harms. Most research projects carry some risks; at the very least there are opportunity costs and inconveniences for the participants. Studies with greater potential risks or harms can only be justified if they have greater potential to generate useful knowledge. Research should have both merit and integrity. A research question needs to answer questions in clinical practice that are important to the community and to clinicians. An ethical approach is thus critical from the instigation of a research project.4

Consumer and primary care clinician involvement

Consumers and stakeholders, such as general practitioners (GPs) and other primary care clinicians, can identify gaps in knowledge and opportunities for change to inform the need for research. They also possess contextual knowledge, either as patients with lived experience or as specialists in general practice/primary care.

Best practice involves collaboration with consumers and communities, from consideration of the need for research to be conducted to the development of the research design and to the implementation, interpretation and dissemination of results.5 For example, consumers are now routinely involved in most cancer research projects. Consumers can join a research team or form a consumer reference group to advise on a project’s progress from instigation through to dissemination. Active clinicians, such as GPs, should ideally be included in all research in this sphere. Primary care clinicians are critical in the dissemination and uptake of the findings and should also be included as part of the research team from their conceptualisation through to implementation. In some cases, consumers and clinicians identify other ethical concerns not noted by ethics committees, for example concern about the burden of the research involvement to patients or clinicians.

Comprehensive literature review

Research can be an expensive and risky endeavour. Researchers need to consider whether the research question has already been answered. Researchers should conduct a comprehensive literature review to ensure that the research question has not already been answered and to inform research question development. In recent times, systematic reviews are being frequently used to inform research studies. Refer to Table 1 for steps in preparing study protocol.

| Table 1. Study protocol |

| Document |

Description |

| Protocol: Literature review |

- Comprehensive literature review (eg systematic review or narrative review) to demonstrate that the research question has not already been answered and to inform research question development

|

| Aim/objectives |

- The protocol should clearly document the research question

|

| Methodology |

- Methodology should be clearly described so as to consider whether the research is feasible and likely to answer the research questions

- Qualitative research provides rich insights into consumer or clinician perspectives on a health issue

- Cohort studies and cross-sectional studies are useful in providing descriptive data and setting the scene for further research

- Randomised controlled trials provide clearer evidence of the effect of interventions but are often time-consuming and expensive to implement

- Mixed-methods approaches provide benefits of both styles of research

|

| Funding |

- Funding source and amount should be documented so as to consider whether the resources are sufficient to ensure that it is possible to complete the project and justify the involvement of participants1

|

| Sample size |

- Evidence should be provided that the planned sample size is likely to answer the research question. For qualitative studies, for example involving interviews, this may involve considering whether the number of participants is likely to provide ‘saturation’; that is, a range of findings with consistent themes emerging. For quantitative studies, this involves consideration of the response rate, primary outcomes and statistical calculation of the required sample size. Recruitment is a key challenge in primary care research for both face-to-face and online research. Response rates of 5–10% are not unusual in GP surveys

- Estimations should be provided of likely withdrawal or failure to follow up participants for intervention studies. Intervention effects may often be less than anticipated, increasing the required sample size for significance

|

| Recruitment plan |

- Documentation of who will be recruited (eg individual patients or clinicians, or practices), inclusion and exclusion criteria and how participants will be selected

- In general practice, researchers need to consider the relationship between researchers and potential participants and how this may affect participation or change the doctor–patient relationships. Recruitment of individual GPs or primary healthcare clinicians can occur through local general practice research networks, paid or unpaid social media posts, flyers or posters

- Primary health network newsletters and the RACGP maintain research project online pages for passive recruiting

|

| Data sources |

- Source of deidentified data from large datasets; for example, general practices,6 primary health datasets (previously from NPS Medicine Insight7 or data from practice networks), state and national hospital datasets, combined datasets (eg LUMOS),8 cohort studies (eg 45 and Up)9 or training datasets (eg ReCeNT)10

- There may be an approval process and cost for obtaining the data

|

| Special populations |

- Evidence that there are safeguards to ensure that consent is informed and freely given (children, people with intellectual disabilities and people with conditions that may impact decision-making capacity, such as dementia and unstable mental illness), that there is a process for consumer involvement and that there is additional support for the consent process. Where a participant lacks decision-making capacity even with support, it may be possible to obtain consent from a person with the legal authority to consent to medical treatments on behalf of the person. However, in some cases informed consent may not be possible, and it may not be possible to proceed

- Documentation of consent procedures for CALD populations (eg the use of interpreters, documents translated into community languages and data collection by researchers experienced in working with CALD groups)

- Researchers should present information regarding whether there may be additional risks of the harm for pregnant women and foetuses

|

| Analysis plan |

- The plan for analysis, and the name of the statistical or qualitative software or analytical methods to be used

|

| Participant feedback |

- Documentation of the mode of presentation of findings to participants (written, pictorial, verbal or in audio or video format, depending on health literacy) and delivery (face to face, email, online) so as to demonstrate respectful feedback to participants

|

| Dissemination plan |

- Process for disseminating results to consumers, clinicians and other stakeholders who may use the findings, demonstrating how this would be done without bias and include both favourable and non-favourable results so as to contribute to the development of knowledge

- Plan for publication, including peer-reviewed academic journals or presentation at conferences. Studies on previously well-researched topics, or studies with smaller datasets in both qualitative and quantitative research are sometimes difficult to publish. Where research findings are not publishable (eg null result or negative findings combined with small sample size or methodological flaws), the dissemination plan should include a plan to make data accessible (pending ethics approval and use) so as to inform future research. Dissemination can include presentation at conferences and dissemination through consumer, clinician or stakeholder networks so as to inform practice and potentially reach a different audience to peer-reviewed publications1

- Plan for translation of findings into practice (eg informing guideline development)

|

| CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse; GP, general practitioner. |

Carefully considered research methodology

The research design should be reviewed for rigour and quality (www.equator-network.org). Researchers should consider whether the planned methods are feasible and able to answer the research question. Some research questions are more difficult to answer and, indeed, may not be answerable without vast resources or expertise. Ethics committees may now require evidence that a research project is feasible in a time frame, with slower recruitment than anticipated being a common challenge in research in primary care.

Researchers should consider the potential risks and harms that may result from research. This may include physical harms, such as the side effects of a medication, but is more likely to include psychological harms, such as disclosure of embarrassing information, being manipulated or being treated disrespectfully. Researchers should consider the economic and opportunity costs to participants involved in the research, including time taken for involvement and the direct or indirect costs to participants. The harm from research needs to be considered at different thresholds to routine clinical care because most research studies do not directly benefit the participants. GPs may also prioritise research that is likely to directly benefit their patients.7

Ethics committees require evidence that participants are adequately informed about the research (eg via a participant information statement) and can freely consent, with these processes being increasingly conducted online (eg verbal consent recorded during qualitative interviews) or implied consent for the completion of electronic surveys.

Evidence of secure data storage and secure data transfers is required by ethics committees, with increasing use of secure electronic or cloud storage becoming the norm rather than paper-based systems.

Researchers should consider the documentation required for research ethics committee applications. The national human research ethics application form (available at https://hrea.gov.au) can facilitate timely and efficient ethics review. Other documents required for ethics committee applications are listed in Table 2.

| Table 2. Documents required for ethics applications |

| Document |

Description |

| Ethics training certificates* |

- Evidence of ethics or clinical trials training by investigators

|

| Researcher CV* |

- CVs demonstrating appropriate research experience (eg primary care research expertise) or specific skills (eg biostatistics or qualitative research expertise)

- Inclusion of active clinicians, such as GPs, as investigators or consumers brings ‘real‑world’ perspective to research

|

| Consumer reference group terms of reference* |

- Membership of reference group, frequency of meeting, roles in governance

|

| Protocol |

- Completed protocol as per Table 1

|

| Timeline* |

- Timeline for research milestones (eg Gantt chart)

|

| Participant information statement |

- Should contain all relevant information about the project that the potential participant should know, including the names and contact details of the investigator team, and contact details for complaints via the ethics committee

- Can be delivered in a range of formats, appropriate to each group of participants (verbally, on paper, as an audio or video recording or electronically) or online for projects using routinely collected data

- Should contain information on how participants could seek additional assistance (eg if a participant experienced distress)

- Should provide information on data management and storage and information on withdrawing consent and data from the study

|

| Consent process |

- Documentation of consent process. Consent, given freely without undue influence, is critical in the ethical conduct of research and should not be viewed as a static process. Participants should be provided opportunities to consider and reflect on their participation and, as far as possible, given the option to re-affirm their continuing involvement

- Consent can be delivered in a range of formats, appropriate to each group of participants (verbally, on paper, as an audio or video recording or electronically). If waiver of consent is sought, explanation should be provided, for example where individual consent is either impossible (eg no access to contact details) or not practicable (eg obtaining consent would be prohibitively resource intensive due to a large number of participants). Such applications should be carefully considered by the researchers and the ethics committees, regardless of how low risk the research study may seem

|

| Research tools |

- Surveys (including paper surveys or copies of online surveys; eg using RedCap or Qualtrics), interview schedule, focus group schedules

|

| Recruitment documents |

- Copies of recruitment flyers, emails, social media posts

|

| Research data management plan |

- Information about secure data storage, data access, duration of storage. Paper documents should be stored in secure, locked environments until they are scanned for secure electronic storage prior to shredding. Electronic data (including audio and video files, survey data and ‘big’ data) should be stored securely using industry-standard encryption, and be stored using enhanced security methods such as multi-factor authentication. Data must be backed up off-site, also in a secure electronic environment

- Information regarding the mode of transfer of data should be provided

- Verification of data location would be required (including whether on-shore or off-shore) and whether storage is managed multinational companies so as to explore which organisation bears the responsibility of protecting research data. The hackability of data is an emerging issue

- Researchers should adhere to the ‘Five Safes’ principles of data useage11,12

- May include support documents from data custodians. May require confidentiality statements from transcribers or external data analysts

- Demonstration of processes to protect confidentiality of participants. Sometimes research data is formally deidentified (ie all personal information is permanently removed from the data), but often the data is anonymised. For example, participants can be given a study ID or a pseudonym to replace personal identifying information. Documents linking participant identifying details and the study ID should be securely stored separately from the rest of the data. Documentation should be provided of the process for withdrawing data for those who no longer consent to its use

- Documentation of the people who collect the data or have access to the data and the process of making datasets accessible to other researchers, on request, with approval from the ethics committee, or where the data forms part of an accessible repository

|

| Data custodian approval* |

- Approval from custodians of large datasets of health data (eg Medical Benefit Scheme or Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule, primary care data or hospital data)

|

| Trial registration* |

- International Clinical Trials Registry Platform or Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registration (clinical trials only)

- Approval from Therapeutic Goods Administration (CTN or CTX schemes; pharmaceutical, device or app trials only)

|

*May not be required by all ethics committees.

CTN, Clinical Trial Notification; CTX, Clinical Trial Exemption; CV, curriculum vitae; GP, general practitioner. |

Experienced research team

Research should be conducted by those who have sufficient experience and competence to conduct it. This maximises the chance that a research project will yield beneficial findings, thus justifying the potential risks and harms. Investigators may now be required to submit evidence of ethics or clinical trials training, as well as curricula vitae to show evidence of research experience. Novice or unaffiliated researchers are highly recommended to approach experienced researchers (eg from departments of general practice at various universities).

Submission to an appropriate ethics committee

Some types of research carry no known risks and therefore may not require approval from an ethics committee; this may include systematic literature reviews or reviews of publicly available online data. Researchers are encouraged to seek an opinion from an National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)-accredited ethics committee if uncertain.13

Quality assurance or quality improvement activities should abide by ethical principles, but ethics committee approval may not be required if the findings are part of routine practice and are for internal use. If the investigator intends to publish (or share the work publicly at a conference), opinion should be sought from an ethics committee.

All health and medical research conducted in Australia needs to be approved by an NHMRC-accredited ethics committee.13 Some research studies may require approvals from multiple ethics committees, usually with one lead ethics committee providing the primary approval and more detailed review of documents.

General practice and primary care research may be submitted to a range of ethics committees, including The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP) National Research and Evaluation Ethics Committee (NREEC). Projects led by university academics, academic registrars or medical students are often approved by university ethics committees. Specialist ethics committees exist in other domains, such as those focusing on pharmaceutical research, social science, justice health or education department research. State health departments may require separate approval from each local health district in addition to the overarching ethics approval. Data collection should not commence until the research has been approved by the relevant ethics committee/s.

Many ethics committees will assess applications for cultural safety, including whether the project team includes investigators or reference groups from subcommunities. If working in languages other than English, bilingual researchers or accredited translators should be considered. Research involving Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, where the community is over-represented or data is specifically identified, should be approved by an ethics committee with expertise in this area, such as the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee in New South Wales.

Many research projects now involve ‘big data’ and additional approval from data custodians; for example, for state health data (eg admissions data), large primary care datasets or Commonwealth health datasets (eg Medicare Benefits Schedule data).

The expression ‘low-risk research’ describes research in which the only foreseeable risk is one of discomfort. In primary care research, this may include the time taken to complete a face-to-face interview. ‘Negligible-risk research’ is where there is no foreseeable risk of harm or discomfort and any foreseeable risk is no more than an inconvenience (eg an online survey). Ethics committees often have a more streamlined pathway for applications that are deemed low or negligible risk. This allows the ‘full’ committee to focus their limited time and resources on research that has higher potential for risk and harm.

Some types of research will be considered as higher risk. For example, genomics research may be associated with implications for the family members of participants, even if they have not personally consented to involvement. Ethics applications for research involving pregnant women or foetuses may need to show no or minimal risk to both groups. Ethics applications for research around conditions that may carry stigma, such as mental health and sexually transmissible diseases, may need to demonstrate extreme care around confidentiality while meeting mandatory clinical requirements.

Responding to ethics committees

NHMRC-constituted ethics committees consist of experienced researchers, lay people, those with legal knowledge and those with spiritual or religious affiliations to provide a range of opinions regarding the conduct of research. Ethics committees have a role in ensuring ethical research, and protecting the community, but may also play a role in highlighting areas where clinicians or researchers themselves may be at risk. The process of ethics committee application is best viewed as an opportunity for feedback and improvement, with the ethics approval process commonly taking time and potentially requiring several resubmissions, in addition to annual reporting.

Conclusion

An approach to research needs to be considered and thoughtful, and often requires time and patience, with documentation for submission to ethics committees designed to support ethical research.

Key points

- Ethics applications are an important step in considering research merit and integrity.

- Consumer and clinician involvement from conceptualisation can improve study design.

- Studies will require a protocol, participant information process and consent process.

- Ethics committees may require evidence of research expertise and training.

- Ethics committee review is an opportunity to improve study design, and to protect the community and researchers.