| Table 2. Secondary cutaneous manifestations of atopic dermatitis in children with skin of colour |

| Secondary cutaneous manifestation |

Description |

| Palmar hyperlinearity |

Accentuation of linear markings on the palm7–10 |

| Dennie-Morgan folds |

Infraorbital fold creases often with surrounding dyspigmentation7–9,11 |

| Labial melanocytic macules |

Pigmented macular freckling usually of the lower lip12 |

| Prurigo nodularis |

Firm, pruritic, abraded, thickened, often dyspigmented nodules13 |

| Lichen amyloidosis |

Rippled hyperpigmented papules coalescing into plaques often over extremities and associated with chronic scratching |

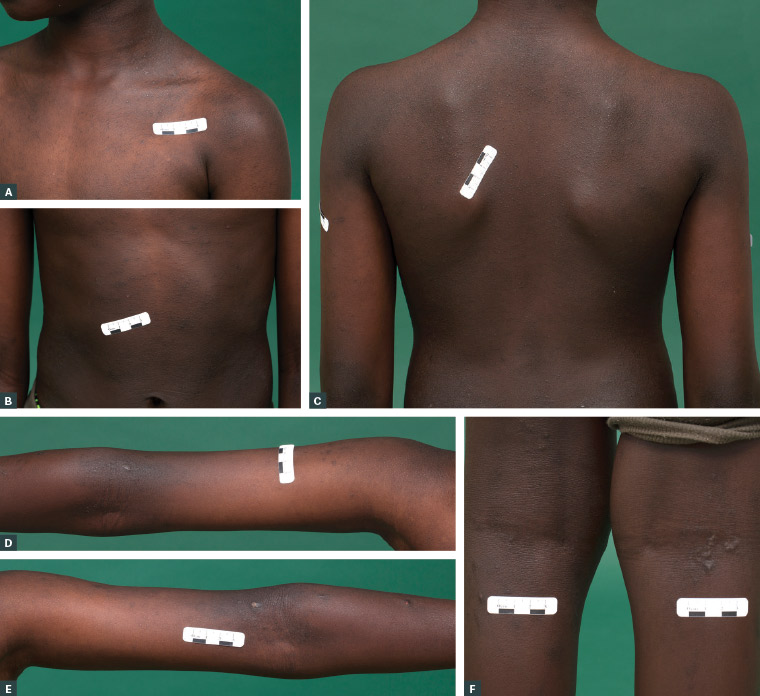

Figure 3. Follicular atopic dermatitis over the chest (A), abdomen (B), back (C), arms (D, E) and lower legs (F) in a boy with richly pigmented skin. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation surrounds the atopic dermatitis lesions over the arms (D, E). Small prurigo nodules are also noted behind the knees (F).

Differential diagnoses

The diagnosis of atopic dermatitis is clinical. However, differential diagnoses in patients with SOC include psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen nitidus and tinea corporis.

Assessment

Erythema is difficult to appreciate in patients with richly pigmented skin. A reliance on erythema might risk underestimation of the severity of atopic dermatitis in this demographic.14 Assessment of the level of greyness might offer greater accuracy in the assessment of ‘erythema’ in those with SOC.6

The challenges in assessing erythema applies to traditional severity assessment scores such as the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI).15 Historically, the EASI was a research tool to assess severity. Online calculators have made the score more accessible, and it can be a useful clinical tool in patients with SOC, who are at greater risk of underestimation of severity. Increasing the erythema score by one point in patients with SOC has also been suggested to avoid underestimation of eczema severity in this group.15

Studies of quality of life (QOL) impairments in children of Asian ethnicity found pruritus, sleep disturbance and embarrassment are important impairments of QOL in this group.16 Most studies published on the impacts of atopic dermatitis on children of Black ethnicity have been conducted in the US. School absenteeism, sleep deprivation, poorer academic performance and impaired social interactions have all been reported with uncontrolled disease.17,18

Head-to-head comparisons of the specific differences in QOL scores among children of different ethnicities are lacking, although mean scores overall have been compared between different ethnicities.16 Sociocultural differences might provide some explanation for differences in QOL scoring, as well as the way in which cultural groups might interpret questionnaires. Of course, social determinants of health unique to families with SOC must also be considered.

Although imperfect, asking the patient and/or parents about their beliefs surrounding atopic dermatitis, how it affects the family and what their main concerns and treatment goals are will help determine how best to support and manage culturally and ethnically diverse patients with atopic dermatitis.

Management

General measures and trigger avoidance

General measures include the avoidance of triggers, such as environmental allergens (contact with grass, dust, animals), rough clothing, hot showers or baths, soaps, detergents, fragrances and creams that might contain irritating ingredients. Using bland emollient moisturisers is the cornerstone in the management of atopic dermatitis in all patients, and can include inert water-free oils or ointments.19

Simple lifestyle modifications include keeping nails short, using light 100% cotton bed coverings, wearing loose cotton pyjamas and avoiding alcohol-based nappy wipes, antiseptic laundry additives, sleeping bags, hot water bottles and rough clothing that can dry, overheat and irritate the skin.20

Washing bedding and clothes in hot water is effective at killing dust mites and helps clear bacteria that can colonise the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Contrary to traditional belief, properly manufactured Merino wool clothing can improve mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis as long as the design is not scratchy.21 Studies reveal that patients from Asian households might use extra bedding, bedroom heating and/or overdress their children more than other cultural groups, which can exacerbate atopic dermatitis.22

Dilute bleach baths assist with decolonisation of Staphylococcus aureus in children with frequent infective exacerbations of eczema. Variations in S. aureus strains have been identified among groups from different ethnic backgrounds.23 This might potentially explain differences in prevalence and disease severity, but does not yet change treatment recommendations.23 Any exudative or weeping lesions should be swabbed for microscopy, culture and sensitivities, and treated accordingly.

When approaching environmental triggers, it is important to frame the discussion around respect of the culture of the child and their family, especially if the trigger might relate to a culturally related clothing, activity or value.

Topical therapies

Topical corticosteroid for atopic dermatitis should not be applied sparingly. Adequate amounts of topical steroid are needed in order to properly break the itch–scratch cycle. Studies have revealed that underuse of topical steroids often leads to more severe and difficult-to-control eczema in the long term.24 The adequate use of topical steroids for flares is necessary to avoid progression and more flares of atopic dermatitis.24,25 Moderate (Class II) topical corticosteroids, including methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% ointment (Advantan, LEO Pharma, Newstead, Qld, Australia), triamcinolone acetonide 0.02–0.05% ointment (ARISTOCORT, Aspen Pharmacare, St Leonards, NSW, Australia) and betamethasone valerate 0.02–0.05% cream (Celestone M, Organon Pharma, Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia), can be used on the face for up to a few days for the treatment of severe flares.26 Potent (Class III) topical steroids, such as betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment (Diprosone, Organon Pharma, Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia), can be used on the torso and limbs until the skin feels normal.26 Patients who require more than two weeks of continuous use without improvement should be considered for referral to a dermatologist.

Topical treatments can be applied with occlusive dressings for small, lichenified and treatment-resistant areas, or with wet dressings for severe flares with widespread skin involvement. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne eczema page provides practical advice on the application of wet dressings.20

Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as pimecrolimus 1% cream and tacrolimus 0.03–0.1% ointment have been widely used in all skin types with good efficacy and comparable safety profiles.27 Although pimecrolimus is available for the treatment of atopic dermatitis on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), tacrolimus needs to be made at a compounding pharmacy and is not PBS subsidised. These agents are effective for atopic dermatitis on the face and neck, as well as flexural areas, and as maintenance therapy in those with severe and chronic atopic dermatitis. The advantage of tacrolimus is that it is compounded in an ointment base that does not contain preservatives, and so does not sting active dermatitis upon immediate application (as opposed to pimecrolimus, which is in a cream). These products should be considered for persistent or difficult-to-control atopic dermatitis on the face. Calcineurin inhibitors can cause a burning sensation during the first few days of use.28

Potent topical steroids can have a bleaching effect and are sometimes incorrectly obtained for this cosmetic effect by patients who attempt to self-treat areas of hyperpigmention.29 Unfortunately, this can precipitate side effects including skin atrophy, telangiectasia and steroid acne. More commonly, however, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is pronounced in children with SOC once the active flare has resolved. The skin is smooth and has reduced pigment (as opposed to the absolute depigmentation seen in vitiligo). This is often a concern for cosmetic reasons and it is important to discuss that the atopic dermatitis has caused this issue, with the treatment being time and gentle sun exposure, not topical steroids. It is also important to explain that this does not represent thinning of the skin. Pityriasis alba describes ill-defined patchy facial hypopigmentation that is thought to be a mild eczematous dermatitis more common in patients with SOC. In these cases, daily pimecrolimus cream is an effective, steroid-sparing treatment.30

Crisaborole 2% ointment is a Therapeutic Goods Administration-approved phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that is used in cases of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis, but it is currently not PBS subsidised.19 The main side effect of crisaborole is stinging and irritation at the application site. Crisaborole has demonstrated efficacy and a low frequency of adverse events in patients with SOC.31

When atopic dermatitis cannot be adequately controlled by topical therapy, a referral to a dermatologist is usually required for additional therapeutic options, as described below.

Phototherapy

Through a dermatologist, phototherapy, usually narrow band ultraviolet light B (NBUVB), is a treatment option in children old enough to stand still in the ultraviolet cabinet who have not responded to general measures and adequate topical therapy. Children younger than six years of age are generally unsuitable candidates for phototherapy. The treatment is subsidised through Medicare in Australia. Phototherapy usually involves short treatment sessions three times a week at a specialist dermatology clinic. Darker skin types take longer to reach therapeutic doses. Patients with SOC are more resistant to short-term side effects, such as burning, erythema, stinging and blistering, but have a higher risk of developing pigmented lesions, such as lentigines, with prolonged therapy.32,33

Systemic therapies

The routine use of systemic corticosteroids for atopic dermatitis is heavily discouraged but might be appropriate for severe acute exacerbations, as a bridge to systemic therapies or phototherapy or prior to a major life event.34 Regimens might involve oral prednisolone at a dose up to 0.5 mg/kg/day for one to two weeks, followed by tapering over one month. Short courses without tapering can lead to rebound flares.35 Steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents such as mycophenolate, methotrexate and cyclosporine can be used for severe refractory cases, but are generally prescribed at the discretion of a dermatologist.35

Targeted therapies

Targeted therapies continue to replace traditional steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate and methotrexate in the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Dupilumab is a new targeted immunosuppressive agent for refractory, severe atopic dermatitis that is PBS approved in children aged >12 years as a fortnightly subcutaneous injection. Clinical trials have shown that dupilumab is effective, including in those with SOC, and might also accelerate the resolution of normal skin tone in patients with postinflammatory dyspigmentation.36 Ethnicity-based comparisons are currently lacking in the literature; however, the data available suggests that dupilumab is well tolerated and efficacious in children regardless of ethnicity.37 Common reported adverse effects are consistent among all ethnic groups and include ocular side effects (eg conjunctivitis), exacerbation of atopic dermatitis, secondary skin infections (bacterial and herpes) and nasopharyngitis.38–41

Oral and topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as upadacitinib (RINVOQ, AbbVie, Mascot, NSW, Australia) have demonstrated effectiveness in severe atopic dermatitis, including in studies from countries in which patients with SOC are predominant.42 Oral upadacitinib has been available on the PBS since February 2022 for patients aged >12 years. Some of the more severe potential adverse effects of JAK inhibitors include immunosuppression, thromboembolism and opportunistic infections.19

Management of complications

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and postinflammatory hypopigmentation are important considerations in children with SOC. Specific treatments are not routinely administered because the dyspigmentation will spontaneously resolve with time as long as the eczema does not recur in the same area.

However, it is important to explain these common sequelae to patients and/or family members and to remind them not to keep treating PIH (flat brown skin staining after the eczema has resolved) with topical therapies targeting atopic dermatitis.

Practitioners should explore how the PIH is affecting the child and their family, because it can be as distressing as the atopic dermatitis itself. If the PIH is prolonged and cosmetically disturbing for the patient, topical tyrosinase inhibitors such as hydroquinone 2–5% could be considered. Hydroquinone 4% cream can be applied twice daily for 8–12 weeks. Patients using hydroquinone should be counselled on the risk of a ‘halo effect’ (a lightening of the surrounding skin) and ochronosis, a rare adverse effect of permanent blue–grey discolouration after using high concentrations for a prolonged period.43 Other treatment options, such as retinoids and azelaic acid, can be used over the counter, but can be irritating, causing flares in sensitive skin.43

In addition to textural changes, scarring from severe and longstanding atopic dermatitis is often associated with dyspigmentation. Skin homogeneity in colour and texture is associated with healthiness and attractiveness in many cultures; it is vital to explore the psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis, especially in patients with dyspigmentation and/or papular changes.44

The psychological burden of atopic dermatitis might result in mental health comorbidities, including anxiety, depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.45,46 Disease severity correlates strongly with school absenteeism, sleep disturbance and friendships, and affects playtime and hobbies.47 Children experiencing psychosocial impacts of atopic dermatitis can benefit from input from allied health workers, including psychologists, social workers, nurse educators and dietitians.48

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis in children with SOC can vary greatly from traditional textbook descriptions. It can be misdiagnosed and its severity underestimated. Complications from atopic dermatitis itself, as well as the treatments provided, might result in inadequate treatment unless the treating doctor is aware of specific nuances in patients with SOC.

Key points

- Traditional textbook descriptions of atopic dermatitis are not representative of atopic dermatitis in patients with SOC.

- Unique psoriasiform, lichenoid, scaly or papular forms of atopic dermatitis are often seen in patients with SOC.

- Unique secondary features of atopic dermatitis in patients with SOC include things like labial pigmentation and prurigo nodularis.

- A grey scale to determine the severity of atopic dermatitis might help avoid underestimating the severity of the condition.

- Possible topical steroid‑induced hypopigmentation and postinflammatory dyspigmentation should be addressed at the initial consultation.

- Cultural views and desires should be considered in the planning of treatment.

- Allied health team members should be involved in patient care to optimise patient outcomes.