Insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea are the two most common sleep disorders and frequently co-occur.1 Comorbid insomnia and sleep apnoea (COMISA) is increasingly recognised as a prevalent condition that is associated with worse health outcomes compared with either insomnia or sleep apnoea alone.1,2

Treatment of patients with COMISA can present unique challenges for general practitioners (GPs). Several recent randomised clinical trials have focused on novel treatment approaches for patients with COMISA.3–5 Targeted treatments for both conditions appear to be the most effective approach to manage COMISA. There are several brief assessment tools and diagnostic, treatment and referral pathways available to GPs to manage patients with COMISA that will be covered in this article.

Aim

This article aims to provide GPs with the up-to-date evidence on the prevalence, health consequences and management options for patients with COMISA.

Insomnia and sleep apnoea

Sleep problems and sleep disorders rarely occur in isolation. Indeed, insomnia and sleep apnoea, the two most common sleep disorders, are frequently comorbid with other chronic physical and mental health conditions, and interact with lifestyle factors/demands that impact sleep quality and quantity. Insomnia and sleep apnoea have previously been viewed as two distinct conditions with separate ‘typical’ presenting features and diagnostic and treatment pathways, as well as different specialist care providers. However, a large body of evidence suggests that many people who have insomnia or sleep apnoea experience both conditions.6,7

Insomnia is characterised by frequent self-reported difficulties initiating sleep, maintaining sleep and/or early morning awakenings from sleep and daytime impairment.8 Chronic insomnia (occurring for ≥3 months) occurs in 6–15% of the general population.9,10 Previous Health of the Nation surveys indicate that sleeping problems are among the most frequent presentations in Australian general practice.11

Obstructive sleep apnoea is characterised by frequent narrowing and collapse of the upper airway during sleep. These respiratory events reduce oxygen saturation and result in cortical arousals/awakenings and daytime impairment.8 Sleep apnoea is underdiagnosed, yet occurs in at least 10% of the general population.12,13 Insomnia and sleep apnoea each increase the risk of mental and physical health conditions, and markedly reduce quality of life,14 with greater risk if both are present.

The comorbidity of insomnia and sleep apnoea was first described in 1973.15 However, there was little research in this field until two studies in 1999 and 2001 reported a 43% prevalence of COMISA in patients with insomnia16 and a 50% prevalence of COMISA in patients with sleep apnoea.17 In 2017, Sweetman et al coined the term ‘COMISA’ and facilitated an increase in research and clinical attention to this field.1

Prevalence

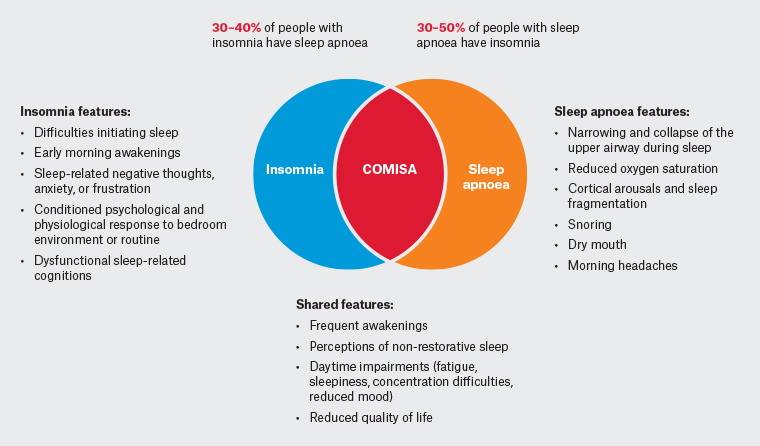

Approximately 30–40% of people with insomnia have comorbid sleep apnoea, and 30–50% of people with sleep apnoea have comorbid insomnia (Figure 1).6,7 Prevalence estimates vary according to the specific sample, diagnostic tools, criteria and threshold for each condition. To date, there has been no large-scale study of the prevalence, predictors or consequences of COMISA in the Australian general practice setting.

Figure 1. Co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnoea (COMISA) is a highly prevalent condition. Click here to enlarge

Characteristics, symptoms and consequences

Most epidemiological research has reported that insomnia is more common in women and that sleep apnoea is more common in men,1,14 although this equalises in women around the time of menopause.18 The prevalence of COMISA is more evenly distributed by gender.19 Sleep apnoea is underdiagnosed in women, potentially due to differences in presenting symptoms that can be missed or misattributed to other conditions. Compared with men, women are more likely to present with insomnia symptoms and non-specific daytime impairments (eg fatigue, lethargy, poor mood), rather than excessive daytime sleepiness, overweight/obesity and loud snoring.20 This can delay sleep apnoea identification and management in women, or result in misattribution of symptoms and inappropriate management (eg with an antidepressant medicine, instead of identification and management of COMISA).

Given that the prevalence of both conditions increases with age, it is unsurprising that increasing age is a risk factor for COMISA. Rates of depression and cardiovascular disease also appear to be higher in patients with COMISA,21,22 and may indicate the need for assessment of sleep disturbance in patients with depression or cardiovascular disease.

Considering the high prevalence of COMISA, it is important to assess for both conditions among patients reporting sleep disturbance of any kind.

Patients with COMISA not only experience difficulties with sleep initiation and/or maintenance but, when sleep is obtained, it is subject to repetitive airway narrowing and closure events that can cause surges in sympathetic activity, cortical arousals and additional awakenings.7 Patients with COMISA have worse sleep, daytime function, mental health, physical health and quality of life than patients with insomnia alone or sleep apnoea alone.1,2,21,22 Three recent population-based studies have reported that people with COMISA have a 50–70% increased risk of all-cause mortality over 10–20 years of follow-up compared with people with neither condition.19,23,24 However, neither insomnia alone nor sleep apnoea alone were associated with mortality risk in fully adjusted models in any study. Only the combination (COMISA) appears to increase mortality risk.

Because insomnia and sleep apnoea both cause significant sleep disruption and daytime symptoms, they can have a similar symptom profile, which can make distinguishing them on history alone extremely difficult (Figure 1). For example, insomnia and sleep apnoea are both associated with daytime impairments such as fatigue, poor mood and concentration difficulties. Unique symptoms of insomnia include self-reported difficulties initiating sleep, long awakenings and early morning awakenings with difficulties returning to sleep, whereas unique symptoms of sleep apnoea include frequent airway narrowing/collapse (witnessed or observed apnoea events) and snoring.

Assessment

Concise, validated assessment tools for insomnia and sleep apnoea exist (Table 1). These tools are also available online through the newly developed online GP insomnia and sleep apnoea guideline.14

| Table 1. Assessment tools for insomnia and sleep apnoea |

| Measure |

Description |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index25 (overall sleep quality) |

A 19-item self-report measure of sleep quality and a screening tool for potential sleep disorders. Overall scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality |

| Insomnia |

| Insomnia Severity Index26 |

A seven-item self-report tool to assess global insomnia severity before and after treatment. It is the most common assessment/outcome measure in insomnia research

The first three items measure nocturnal symptoms that are unique to insomnia and the remaining four items measure consequences that are shared by insomnia and sleep apnoea. A score of ≥15 indicates at least moderate insomnia |

| Sleep diary27 |

A one-week sleep diary allows patients to record information about time in bed and timing of sleep/wake patterns each morning after getting out of bed |

| Sleep apnoea |

| OSA5028 |

A four-item questionnaire to assess for a high-risk of sleep apnoea |

| STOP-Bang29 |

An eight-item self-report questionnaire to assess for a high-risk of sleep apnoea |

| Overnight sleep study (polysomnography)14 |

The ‘gold standard’ measure of OSA presence and severity

GPs can refer patients with an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of ≥8 and high-risk OSA (according to either an OSA50 score ≥5 or a STOP-Bang score ≥3) for a home-based or laboratory sleep study |

| Daytime impact |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale30 |

An eight-item self-report measure of sleep propensity in different situations. Scores ≥16 indicate severe excessive daytime sleepiness

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is often used as a follow-up measure to assess improvement in daytime sleepiness after treatment |

| Flinders Fatigue Scale31 |

An eight-item self-report measure of fatigue severity and experiences during different times of day. Scores >10 indicate significant fatigue

Effective treatment of OSA and insomnia also frequently leads to improvement in symptoms of daytime fatigue |

Several standardised questionnaire measures of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) are available on the Sleep Health Primary Care Resource (www.sleepprimarycareresources.org.au/).

GP, general practitioner. |

GPs can assess patients for a high risk of sleep apnoea using the self-report questionnaires. Patients with a score ≥8 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and a high-risk obstructive sleep apnoea score (according to the OSA50, STOP-Bang, or Berlin questionnaires) can claim a Medicare benefit for a home-based or laboratory-based sleep study (Table 1). If patients are not eligible for a GP referral for a sleep study with a Medicare benefit, they may be referred to a sleep specialist for further investigation and specialist referral for an overnight sleep study, or referred by a GP for a sleep study without any Medicare benefit.

Treatment

The recommended first-line treatment for insomnia is cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-i), whereas the recommended first-line approach for moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnoea management is lifestyle and weight management advice for people with overweight/obesity, combined with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. Additional therapies for selected patients with sleep apnoea include mandibular advancement devices, positional therapies and surgery. Management approaches for insomnia alone and sleep apnoea alone are described in the online GP insomnia and sleep apnoea guideline.14

Patients with COMISA can present to GPs with unique and complex treatment needs. For example, patients with COMISA are less likely to initially accept CPAP therapy and use CPAP for fewer hours per night than patients with sleep apnoea alone.32,33 CPAP therapy may exacerbate pre-existing insomnia symptoms or may be viewed as a ‘threat’ to sleep, which is highly valued and protected by many patients with insomnia. Ultimately, negative initial experiences often lead to high rates of CPAP rejection and suboptimal use in COMISA. This indicates that adjunct/additional therapy approaches, including initial treatment with CBT-i, may be considered. Second-line therapies for sleep apnoea, including dental devices and positional devices, have received limited research attention in COMISA.7 GPs play an important role in investigating reasons for CPAP rejection and poor compliance, including claustrophobia/anxiety, facial soreness/irritation and nasal obstruction, and ongoing referral to an ear, nose and throat specialist for further investigation might be appropriate.

Although not recommended as the first-line approach, sedative-hypnotic medicines are still commonly prescribed to manage insomnia. These medicines are not recommended in people with sleep apnoea due to the potential depressant effects on respiratory control in some patients. Emerging research is investigating targeted pharmacotherapies/combination therapies for sleep apnoea in patients with specific underlying mechanisms in controlled clinical trials.34 Similarly, off-label use of specific antidepressant and antipsychotic medicines for insomnia may exacerbate sleep apnoea in some patients.35 This is an important concern given the high rate of undiagnosed sleep apnoea among patients with insomnia, the comorbidity of sleep disorders and depression and some trends for an increase in off-label antidepressant medicines for insomnia.36 Finally, CBT-i is effective in the presence of untreated sleep apnoea.3–5,14,37 However, one of the most effective components of CBT-i, ‘bedtime restriction therapy’, can cause a small initial increase in daytime sleepiness among people with untreated sleep apnoea and may require close oversight and tailored delivery to reduce sleepiness-related risks.38

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 1040 people with COMISA found that CBT-i leads to large improvements in insomnia symptoms among those with treated and untreated comorbid sleep apnoea.39 Several recent randomised controlled trials in patients with COMISA have investigated the effect of CBT-i on improvements in insomnia symptoms, as well as effects on subsequent use of CPAP therapy. Three studies have reported that therapist-delivered CBT-i improves insomnia in the presence of untreated sleep apnoea,3–5 and two studies have observed that CBT-i increases average nightly CPAP use by about one hour per night compared with no-treatment control.3,4 CBT-i programs have also been translated to self-guided modalities. A Norwegian study reported that a self-guided text-based CBT-i program did not improve insomnia symptoms or subsequent CPAP use in patients with COMISA compared with sleep hygiene control.40 CBT-i programs have also been translated to self-guided interactive digital programs that can offer personalised insomnia assessment and management advice. Sleep restriction therapy, one of the most effective components of CBT-i is associated with a short-term increase in daytime sleepiness during the first one to three weeks of treatment.38 Because patients with COMISA may commence treatment with some pre-existing daytime sleepiness, weekly changes in daytime sleepiness should be monitored closely during digital and therapist-delivered CBT-i to avoid any increased risk of sleepiness-related accidents. An ongoing randomised controlled trial in the USA investigating the effect of an interactive digital CBT-i program on patients with COMISA has reported promising interim results.41 An Australian study investigating the effect of an interactive digital CBT-i program tailored for insomnia and COMISA is available to general practice patients through a GP referral.42

The specific order that treatments for insomnia and sleep apnoea are commenced, or ‘sequenced’, for COMSIA has received little attention.5 Current evidence indicates that treatment for both disorders should be offered to patients with COMISA, and the sequence and specific modality should be guided by patients’ preferences, the chief complaint, the temporal onset and severity of the two conditions and the potential sleepiness-related accident risk.43 Preliminary studies indicate that CBT-i as the initial treatment may improve insomnia and increase subsequent acceptance and use of CPAP therapy.4 Ongoing research aims to develop more personalised and effective treatment approaches for COMISA and to implement these management approaches into the primary care and specialist sleep clinic settings.39

Some patients may be suitable for referral to a specialist sleep physician and/or psychologist for further investigation and management, rather than management in general practice (eg with brief or digital CBT-i programs). Referral to a specialist sleep physician may be considered for a minority of patients with diagnosed/suspected comorbid sleep, respiratory or cardiac disorders, neuromuscular disease, body mass index ≥45 kg/m2, alcohol abuse, chronic opioid use or a risk of sleepiness-related accidents. Full specialist referral recommendations are outlined in the online GP insomnia and sleep apnoea guideline (OSA; Investigations and Referral [www.sleepprimarycareresources.org.au/osa/investigations-and-referral?q=osa%20referral]).14

Referral to a specialist ‘sleep’ psychologist may also be considered for a minority of patients who are currently pregnant or caring for very young infants, those with seizure disorders (which may be exacerbated by sleep deprivation resulting from sleep restriction therapy in some patients), severe or uncontrolled psychiatric disturbances, excessive daytime sleepiness, people who drive for work and shift workers.14,44 The Australasian Sleep Association and the Australian Psychological Society are currently collaborating on a suite of education programs to increase the number of psychologists with training in insomnia assessment and CBT-i delivery.

Insomnia is an eligible condition for a Medicare-subsidised GP mental health treatment plan referral, using Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item numbers 2715 or 2717.45 Patients with sleep apnoea qualify for a GP management plan using MBS Item 721, and many will also qualify for a team care arrangement using MBS Item 723. All patients who have a gold Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) card, and some who have a white DVA card, can be referred for a range of psychological and other services without any care plan having to be created.46 They are also eligible for the creation of a GP management plan using MBS Item 721, and many will also qualify for a team care arrangement using MBS Item 723.

Conclusion

Insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea are the two most prevalent sleep disorders, and many people have both disorders (Box 1). COMISA is a highly prevalent condition that is associated with poor mental and physical health outcomes, as well as complex diagnostic, treatment and referral decisions. Current evidence indicates that treatments for both disorders should be offered to patients with COMISA. CBT-i is effective and safe in the presence of untreated sleep apnoea, and may increase the subsequent use of CPAP therapy.

| Box 1. Take-home messages |

- Insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea are the most prevalent sleep disorders.

- Insomnia and sleep apnoea frequently coexist (COMISA).

- COMISA is associated with worse health consequences than either disorder alone.

- People with COMISA may not respond well to CPAP therapy alone.

- Initial treatment with CBT-i is recommended to improve insomnia and potentially increase the use of CPAP therapy.

|

| CBT-i, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia; COMISA, comorbid insomnia and sleep apnoea; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure. |

The online GP insomnia and sleep apnoea guideline provides more detailed information about the risk factors, consequences, assessment and management of both insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea.14

Key points

- COMISA is a prevalent and debilitating condition.

- GPs can use standardised self-report questionnaires to assess for insomnia.

- GPs can assess patients at high-risk of sleep apnoea with self-report questionnaires and refer qualifying patients for a sleep study for which patients can claim a Medicare benefit.

- Treatment for both disorders should be offered to all patients with COMISA.

- CBT-i improves insomnia symptoms and may increase subsequent acceptance and use of CPAP therapy in patients with COMISA