Sore throat is one of the most common and frequently seen complaints in children.1 Because viral infections are responsible for most cases of acute pharyngitis in children, most paediatric patients with a sore throat do not require antibiotic therapy.2 However, antibiotics are frequently and inappropriately prescribed for children with a sore throat, even in high-income countries.3,4 This results in considerable spending on unnecessary healthcare and in antimicrobial resistance in the community.5,6

The most frequent bacterial cause for which antibiotic therapy is definitely required in the case of acute pharyngitis is Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus (GABHS), seen in 30% of cases of sore throat in the paediatric population.7 Streptococcal infections can lead to life-threatening non-suppurative complications (eg acute rheumatic fever, glomerulonephritis and paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders) and suppurative complications (peritonsillar abscess, septic jugular vein thrombophlebitis, Vincent’s angina) requiring emergency medical or surgical intervention.8 Complications such as acute rheumatic fever, which are responsible for significant mortality and morbidity, are 100–200% more prevalent in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries.9 However, because the signs and symptoms of GABHS pharyngitis cannot generally be differentiated from other causes of sore throat, diagnosis is difficult.10 GABHS pharyngitis has potentially life-threatening complications, whereas viral pharyngitis does not even require antibiotics; so, the decision process is important for clinicians. Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines are available to standardise clinician approaches.7,11–13

COVID-19 spread across the globe at an alarming pace and became the first pandemic of the 21st century. COVID-19 symptoms include cough, sore throat, high temperature, diarrhoea, headache, muscle or joint pain, fatigue and a loss of the sense of smell and taste. Treatment is usually supportive and the role of antiviral agents has not been established. The incidence of sore throat in children diagnosed with COVID-19 infection is 10–20% and has a summary positive likelihood ratio, meaning that its presence increases the probability of having an infectious disease other than COVID-19.14 During the rapid spread of the disease in Türkiye, everyone with a sore throat had a compulsory COVID-19 test before seeing a doctor, and those with COVID-19 were treated in separate institutions. There is currently no evidence to support further polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for COVID-19 in any individual presenting only with upper respiratory symptoms, such as sore throat, coryza or rhinorrhoea.15

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes and practices of general practitioners (GPs) and paediatricians toward GABHS tonsillopharyngitis in Türkiye.

Methods

Study design and registration

This cross-sectional study was performed in Türkiye between January and March 2022. General practice interns, GPs, GP specialists, paediatric interns and specialist paediatricians were included in the study. Following six years of basic medical education, physicians in Türkiye are able to take part in the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients in all health institutions. After basic medical training, the physician is then entitled to undergo specialist training by passing the national medical specialisation examination. In Türkiye, family medicine residency lasts three years and paediatrics residency lasts four years.

In this study, a self-administered online questionnaire was used to investigate clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning the management of sore throats. The COVID-19 omicron variant wave commenced while the study was being planned and the requisite approvals were being obtained. Infection rates increased during this time and mask-wearing was made compulsory in all settings. It was therefore decided to conduct the study online.

The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Health Sciences, Samsun Education and Research Hospital Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (BAEK2021/354).

The questionnaire was produced via a scan of the literature,16–18 keeping in mind national GABHS guidelines.7,13 The opinions of two professors of paediatric medicine, two professors of general practice medicine, and one ear, nose and throat specialist were obtained regarding the cases in the questionnaire. The cases assumed their final form once those opinions were received. A pilot study was performed with five GPs and five paediatricians who were not included in the study, and the questionnaire thus assumed its final form. Information about the study was distributed by means of social media and mail groups. The online questionnaire was sent to 250 GPs and 250 paediatricians, identified through a WhatsApp and email group of pediatricians with 250 pediatricians from Türkiye. Responses were received from 50.4% of GPs (126/250) and 42.4% (106/250) of paediatricians.

Participants and recruitment

The participants were informed about the aim of the research, how long the questionnaire should take to complete, the identity of the researchers and how the data would be stored in a section at the beginning of the form. Written informed consent was obtained online before the participants completed the self-administered questionnaire, which consisted of 26 questions that could be completed in 10 minutes.

The questionnaire contained questions regarding the clinicians’ demographic characteristics, their year of graduation from medical school and title. Three case scenarios, one each with bacterial, viral and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) findings, were presented to the clinicians to evaluate their knowledge and management of sore throat.

The first case was a 10-year-old girl with a sore throat persisting for three days, but with no cough. Exudative, hyperaemic tonsils and tender cervical lymph nodes were present at physical examination. Her body temperature was 38.3°C.

The second case was a seven-year-old boy presenting with a sore throat and fever for the previous two days, but with normal body temperature and large pink tonsils with no exudate at physical examination. No other abnormality was detected.

The third case was a sore throat and weakness persisting for two days in a five-year-old girl. Petechiae on the bilateral tonsils and tender cervical lodes were observed. Her body temperature was 38°C.

The clinicians were asked about their preliminary diagnoses in these cases, which tests they regarded as appropriate, initiation of antibiotic therapy, which antibiotic they would prescribe (if applicable) and whether they would administer symptomatic treatment.

Analyses

Study data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical data were compared using Chi-squared tests. Two-sided P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

In all, 236 physicians (126 paediatricians, 106 GPs) were included in the study; 25.4% of participants were general practice interns, 21.1% were paediatric interns, 9.9% were GPs, 10.3% were GP specialists and 33.2% were paediatricians. Women represented 59.1% of study population. The mean age of the study group was 35.1±7.8 years (range 25–55 years). The mean time since graduation from medical school was 10.0±7.6 years (range 1–32 years). There were no significant differences in terms of age, sex or time since graduation between the GP and paediatrician groups (Table 1).

| Table 1. Clinicians’ demographic data and responses to the cases |

| |

Total (n=232) |

Paediatrician (n=126) |

GP (n=106) |

P-value |

| |

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

| Sex |

| Male |

95 (40.9) |

47 (37.3) |

48 (45.3) |

0.218 |

| Female |

137 (59.1) |

79 (62.7) |

58 (54.7) |

|

| Age (years) |

| 25–45 |

202 (87.1) |

113 (89.7) |

89 (84.0) |

0.196 |

| >45 |

30 (12.9) |

13 (10.3) |

17 (16.0) |

|

| Years since graduation |

| 0–10 |

143 (61.6) |

74 (58.7) |

69 (65.1) |

0.321 |

| >10 |

89 (38.4) |

52 (41.3) |

37 (34.9) |

|

| Diagnosis |

| GABHS |

| Incorrect |

50 (21.6) |

34 (27.0) |

16 (15.1) |

0.028 |

| Correct |

182 (78.4) |

92 (73.0) |

90 (84.9) |

|

| Viral URTI (non-EBV) |

| Incorrect |

21 (9.1) |

12 (9.5) |

9 (8.5) |

0.785 |

| Correct |

211 (90.9) |

114 (90.5) |

97 (91.5) |

|

| EBV |

| Incorrect |

96 (41.4) |

49 (38.9) |

47 (44.3) |

0.401 |

| Correct |

136 (58.6) |

77 (61.1) |

59 (55.7) |

|

| Test request |

| GABHS |

| Yes |

121 (52.2) |

74 (58.7) |

47 (44.3) |

0.029 |

| No |

111 (47.8) |

52 (41.3) |

59 (55.7) |

|

| Viral URTI (non-EBV) |

| Yes |

61 (26.3) |

27 (21.4) |

34 (32.1) |

0.067 |

| No |

171 (73.7) |

99 (78.6) |

72 (67.9) |

|

| EBV |

| Yes |

140 (60.3) |

74 (58.7) |

66 (62.3) |

0.584 |

| No |

92 (39.7) |

52 (41.3) |

40 (37.7) |

|

| Antibiotic therapy |

| GABHS |

| Yes |

197 (84.9) |

102 (81.0) |

95 (89.6) |

0.066 |

| No |

35 (15.1) |

24 (19.0) |

11 (10.4) |

|

| Viral URTI (non-EBV) |

| Yes |

35 (15.1) |

22 (17.5) |

13 (12.3) |

0.271 |

| No |

197 (84.9) |

104 (82.5) |

93 (87.7) |

|

| EBV |

| Yes |

78 (33.6) |

39 (31.0) |

39 (36.8) |

0.348 |

| No |

154 (66.4) |

87 (69.0) |

67 (63.2) |

|

| Symptomatic therapy |

| GABHS |

| Yes |

228 (98.3) |

123 (97.6) |

105 (99.1) |

0.402 |

| No |

4 (1.7) |

3 (2.4) |

1 (0.9) |

|

| Viral URTI (non-EBV) |

| Yes |

205 (88.4) |

103 (81.7) |

102 (96.2) |

0.001 |

| No |

27 (11.6) |

23 (18.3) |

4 (3.8) |

|

| EBV |

| Yes |

205 (88.4) |

108 (85.7) |

97 (91.5) |

0.170 |

| No |

27 (11.6) |

18 (14.3) |

9 (8.5) |

|

| EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GABSH, Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus; GPs, general practitioners; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection. |

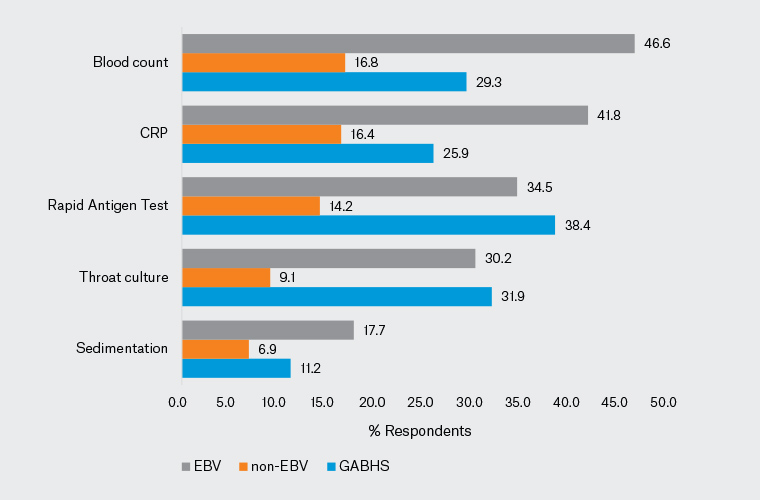

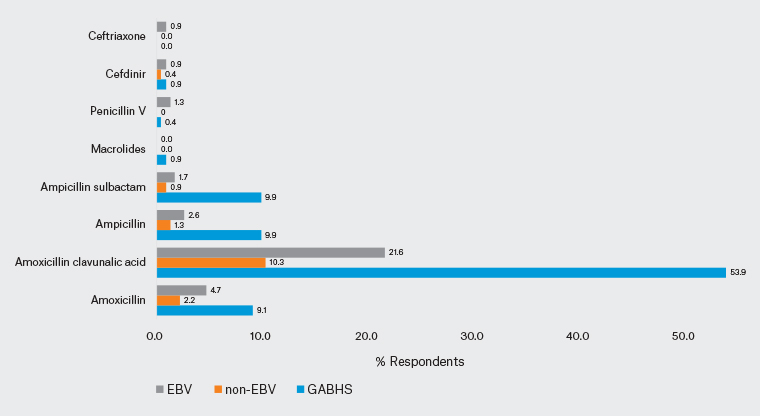

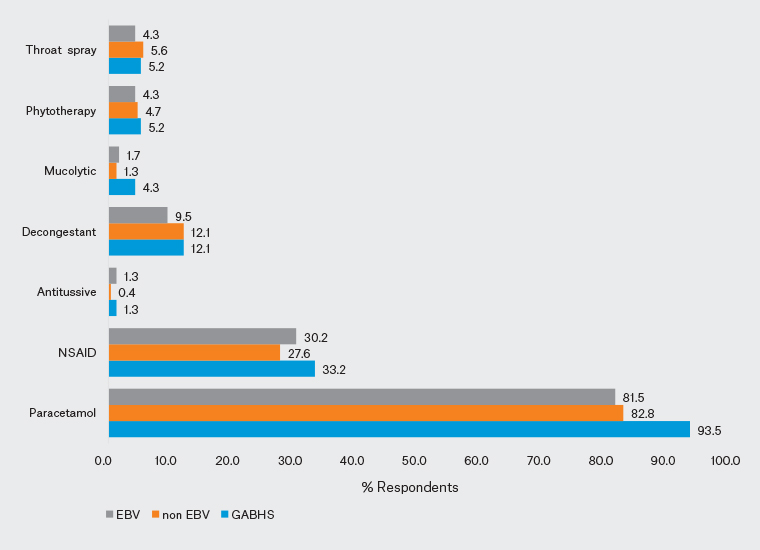

Case 1

In case 1, 78.4% of clinicians reported suspecting sore throat caused by GABHS. Seventy-three per cent of paediatricians and 84.9% of GPs produced an appropriate diagnosis; the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.028). In addition, 52.2% of clinicians (58.7% of paediatricians; 44.3% of GPs) stated that they would request a test. The difference in test requests between the paediatricians and GPs was statistically significant (P=0.029). A rapid antigen test was requested by 38.4% of clinicians, and a throat culture by 38.4% (Figure 1). In addition, 84.9% of clinicians reported that they would consider prescribing antibiotics (81% of paediatricians; 89.6% of GPs; P=0.066). Moreover, 97.6% of paediatricians and 99.1% of GPs planned to prescribe symptomatic treatment. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was selected by 53.9% of participants as antibiotic therapy, whereas 93.5% reported that they would prescribe paracetamol as symptomatic treatment (Figures 2,3).

Figure 1. Distribution of the laboratory tests requested for each of the three cases by the study participants. Click here to enlarge

CRP, C-reactive protein; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GABSH, Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus.

Case 2

The second case involved a child with symptoms and findings suggestive of a non-EBV upper respiratory tract infection (URTI); 90.9% of clinicians suspected a viral URTI and 73.7% stated that they would not request a test. An accurate diagnosis was made by 90.5% of paediatricians and 91.5% of GPs; 21.4% of paediatricians and 32.1% of GPs reported that they would request tests (16.6% would request a complete blood count and 16.4% would request C-reactive protein [CRP]; Figure 1) and 15.1% of clinicians (17.5% of paediatricians, 12.3% of GPs) stated that they would initiate antibiotic therapy. The most popular antibiotic was amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (10.3%; Figure 2). Symptomatic treatment was chosen by 88.4% of clinicians (81.7% of paediatricians, 96.2% of GPs). Significantly more GPs favoured symptomatic treatment in non-EBV viral URTI (P=0.001). Paracetamol was the most popular symptomatic treatment (82.8%; Figure 3).

Figure 2. Distribution of participants’ antibiotic preferences for each of the three cases. Click here to enlarge

EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GABSH, Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus.

Case 3

In the third case, the responses were split: the clinical impressions of 58.6% of clinicians favoured a sore throat caused by EBV, whereas the clinical impressions of the remaining clinicians were divided between non-EBV viral URTI/GABHS. A correct diagnosis was made by 61.1% of paediatricians and 55.7% of GPs. Fewer clinicians (60.3%) reported that they would request tests than in the other two cases, with 58.7% of paediatricians and 62.3% of GPs planning tests: 46.6% of the participants would request a complete blood count, 41.8% would request CRP, 34.5% would request a rapid antigen test and 31.2% would request throat culture (Figure 1). One in three clinicians would consider initiating antibiotic therapy for the EBV case (31% of paediatricians, 36.8% of GPs). The most frequently selected antibiotic was amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (21.6%; Figure 2). In all, 88.4% of clinicians (85.7% of paediatricians, 91.5% of GPs) planned to initiate symptomatic treatment. Paracetamol was the most frequently indicated symptomatic treatment (81.5%; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Distribution of symptomatic therapies recommended by the participants for each of the three cases. Click here to enlarge

EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GABSH, Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

When the clinicians were asked about the reasons why they initiated antibiotic therapy in patients with a sore throat, the most frequent response was the leukocyte count, CRP and sedimentation elevation among the laboratory findings (74.6%), followed by the presence of bacterial infection in the throat swab (Table 2). The results showed that 21.1% of physicians would prescribe antibiotics if the families so requested. Fewer GPs stated that they would prescribe antibiotics; a significantly higher proportion of paediatricians stated that they would prescribe antibiotics (P=0.001). More GPs and fewer paediatricians stated that they would prescribe antibiotics in the presence of physical examination findings accompanying the sore throat (P=0.037). More GPs elected to prescribe antibiotics if only fever accompanied the sore throat (P=0.02). No differences were observed in terms of initiating antibiotic therapy between paediatricians and GPs in case of comorbidity affecting the immune system, a reduced risk of non-suppurative complications or uncertain diagnosis (Table 2).

| Table 2. Participants’ reasons for initiating antibiotic therapy in patients with sore throat |

| Reasons for initiating antibiotic therapy in patients with sore throat |

Total |

Paediatricians |

GPs |

P-value |

| n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

| Presence of comorbidity affecting the immune system |

| No |

140 (60.3) |

81 (64.3) |

59 (55.7) |

0.181 |

| Yes |

92 (39.7) |

45 (35.7) |

47 (44.3) |

| To reduce the risk of non-suppurative complications (rheumatic fever, glomerulonephritis) |

| No |

94 (40.5) |

55 (43.7) |

39 (36.8) |

0.289 |

| Yes |

138 (59.5) |

71 (56.3) |

67 (63.2) |

| Diagnostic uncertainty |

| No |

176 (75.9) |

98 (77.8) |

78 (73.6) |

0.457 |

| Yes |

56 (24.1) |

28 (22.2) |

28 (26.4) |

| Antibiotics requested by families |

| No |

183 (78.9) |

89 (70.6) |

94 (88.7) |

0.001 |

| Yes |

49 (21.1) |

37 (29.4) |

12 (11.3) |

| Physical examination findings (excluding body temperature) |

| No |

118 (50.9) |

72 (57.1) |

46 (43.4) |

0.037 |

| Yes |

114 (49.1) |

54 (42.9) |

60 (56.6) |

| Body temperature above 38°C |

| No |

107 (46.1) |

70 (55.6) |

37 (34.9) |

0.002 |

| Yes |

125 (53.9) |

56 (44.4) |

69 (65.1) |

| Laboratory findings A |

| No |

59 (25.4) |

30 (23.8) |

29 (27.4) |

0.536 |

| Yes |

173 (74.6) |

96 (76.2) |

77 (72.6) |

| Bacterial findings in throat swabs (without growth on throat culture or RAT) |

| No |

87 (37.5) |

42 (33.3) |

45 (42.5) |

0.153 |

| Yes |

145 (62.5) |

84 (66.7) |

61 (57.5) |

| To reduce the risk of suppurative complications (eg peritonsillar abscess) |

| No |

181 (78.0) |

100 (79.4) |

81 (76.4) |

0.589 |

| Yes |

51 (22.0) |

26 (20.6) |

25 (23.6) |

| A Laboratory findings included elevated leukocyte count, C-reactive protein and sedimentation rate.

GP, general practitioner; RAT, rapid antigen test. |

Discussion

Summary

It is of great importance for GPs and paediatricians involved in the management of sore throats in children to provide a correct diagnosis and treatment. Preventing complications that may develop in association with the illness and reducing problems such as antibiotic resistance are vitally important.

Although approximately three-quarters of clinicians in this study correctly identified GABHS as such, almost all physicians correctly diagnosed the case of non-EBV viral URTI. However, the level of correct diagnoses in the EBV case was low. Although infectious mononucleosis, the primary EBV infection, is generally asymptomatic, symptoms such as sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, fever, fatigue, hepatosplenomegaly, palatal enanthema, eruptions and lymphocytosis may also occur. EBV can frequently be confused with a viral or bacterial infection.19 In that case, the guidelines and auxiliary laboratory parameters for diagnosis assume particular importance. It is important to identify GABHS cases, because complications can develop if it is not diagnosed and appropriate treatment is not administered.

Throat culture is regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of GABHS and helps with the identification of the cause of sore throat. However, clinicians may only learn of the cause of the sore throat after 48 hours have elapsed.20 This can create problems with control, particularly in families of low socioeconomic and education levels and with large numbers of children. Therefore, a more rapid diagnostic method is needed. Only approximately one-quarter of physicians in the present study requested a throat culture for the diagnosis of GABHS, whereas 38.4% requested a rapid antigen test in the GABHS case.

Comparison with existing literature

In a vignette study involving the use of rapid antigen streptococcus tests (RAST) among GPs in France, 66% of participants reported that they would use a RAST.21 The rates of RAST use are variable. One extensive review of 59 papers examined the sensitivity and specificity of RAST in the diagnosis of GABHS pharyngitis and described it as highly sensitive and quite specific for GABHS in adults, but exhibiting low sensitivity and specificity in children.22 However, a study from India reported that RAST exhibited high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of GABHS pharyngitis.23 Although this appears confusing, the ability to get a more rapid result from the RAST compared with throat culture and its acceptable cost mean that it is very beneficial in terms of starting treatment by identifying cases of GABHS under conditions in which follow-up is difficult. The low rate of requesting rapid antigen tests in the present study may be due to these tests not being easily accessible in health institutions.

In a scenario study from Australia, 89.3% of clinicians also prescribed antibiotics for bacterial infection.11 Most physicians (84.9%) in the present study also elected to prescribe antibiotics for the GABHS case, but not for viral URTI. One-third of physicians considered initiating antibiotics for EBV. The first-choice antibiotic in the treatment of GABHS is either phenoxymethylpenicillin or amoxicillin.11,24 In the present study, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was the most frequently prescribed antibiotic in the GABHS case (53.9%), with only one in 10 physicians preferring amoxicillin. In a study involving paediatricians in Italy, most participants selected amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (55%) and amoxicillin was selected by 34% for the treatment of GABHS pharyngitis.25 GPs in France favoured amoxicillin (72.8%) for the treatment of GABHS pharyngitis.21 In the present study, there was no significant difference in antibiotic preferences between paediatricians and GPs. Penicillin/amoxicillin was selected at a very low rate, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was also recommended at very high rates in the other cases in the event of antibiotic therapy being given.

Implications for research and practice

Rational antibiotic use is important in order to avoid the development of resistance. To this end, developing and updating guidelines for physicians, disseminating evidence, auditing and feedback and public information campaigns will all be useful.

The high number of physicians who reported that they would give symptomatic therapy most frequently prescribed paracetamol. A prospective randomised controlled double-blind study investigating the efficacy of intravenous dexketoprofen and paracetamol in resolving pain caused by sore throat reported that both exhibited similar analgesic effects by reducing throat pain to a comparable extent.26 However, German guidelines recommend ibuprofen or naproxen for symptomatic therapy in acute pharyngitis and only offer weak support for the use of throat preparations (pastilles, gargle solutions or sprays) containing local anaesthetics and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.27 It should be remembered that the throat preparations prescribed as symptomatic therapy provide, at best, low effectiveness for a brief period against self-limiting symptoms.

A study from 2018 investigating the approach toward URTIs among paediatricians in China found that they most frequently prescribed antibiotics for children with fever persisting for more than five days (54%), followed by the presence of a yellowish–greenish nasal discharge (46.6%).28 In addition, 10.6% of the paediatricians in that study reported that they would prescribe antibiotics if requested to do so by the families.28 In the present study, the most important criteria for clinicians in terms of prescribing antibiotics were the presence of laboratory results supporting bacterial infection and bacterial findings in throat swabs. Moreover, 21.1% of physicians stated that they would prescribe antibiotics if the families so requested.

Strengths and limitations

The particular strength of this study is that it includes a systematic analysis of data on multidisciplinary approaches to diseases commonly encountered in the paediatric population. However, it also has a number of limitations. The number of physicians taking part in this study was relatively low and therefore the results may not be reflective of the entire population of physicians in Türkiye. The responses also rely on the honesty of the participants and their understanding of the questions. This may have caused a deviation in the results. In addition, the assessments of the scenarios and the questions posed online may not exactly reflect the approach to real cases encountered in the clinical setting.

Conclusion

Although the approaches of paediatricians and GPs regarding the diagnosis of pharyngitis in this study were generally satisfactory, the results revealed a low level of knowledge concerning therapeutic options. The rate of prescription of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was very high, which emphasises the need for physicians’ knowledge of control strategies for GABHS pharyngitis to be updated. The establishment of national guidelines in light of global practice will provide clearer approaches to the treatment of pharyngitis for physicians.