In Australia, approximately 8% of people have been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and a further 11% exhibit symptoms suggestive of OSA.

1 In 2019, OSA cost the Australian healthcare system $370 million, representing 57% of total spending on sleep disorders.

2 Further, treating OSA has been shown to be cost-effective.

3 OSA has been identified as an underlying factor in difficult-to-treat conditions such as hypertension and might contribute to the development of other treatment-resistant conditions.

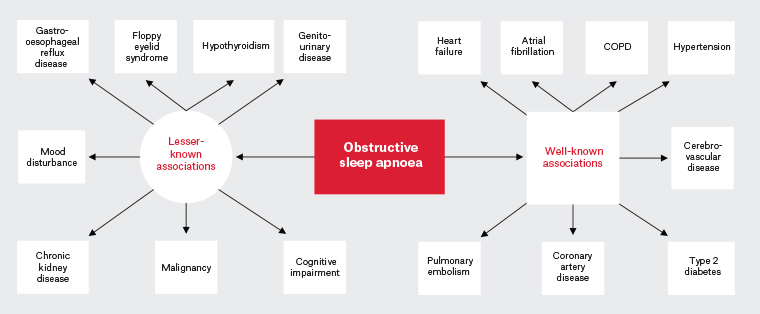

4 Given the high cost and high prevalence of OSA in Australia, it is crucial that clinicians recognise the wide array of diseases it is associated with (Figure 1).

4–9

Figure 1. Current and emerging conditions associated with obstructive sleep apnoea.4–9 Click here to enlarge

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

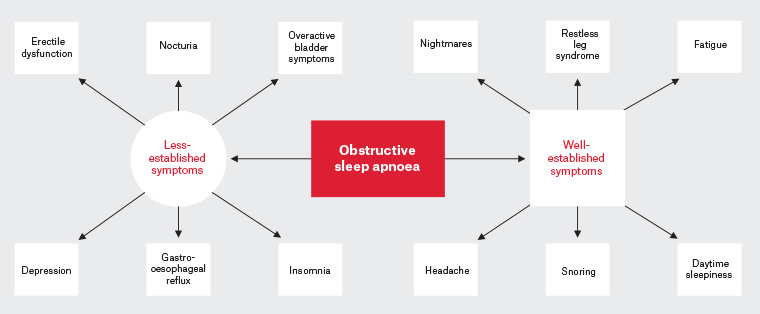

Chronic intermittent hypoxia is thought to underpin the cardiorespiratory complications in OSA and additional associations are emerging across multiple systems (Figure 2).6,7,9,10 The connections between OSA and urological symptoms are becoming increasingly recognised; common symptoms include nocturnal polyuria (NP), overactive bladder syndrome (OAB), and erectile dysfunction (ED).7,9,11

Figure 2. Current and emerging symptoms associated with obstructive sleep apnoea.4,5,7,9–11 Click here to enlarge

OSA treatment includes lifestyle modifications, continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP) and management of comorbid conditions.12 Recent evidence suggests that CPAP treatment in OSA can lead to improvements in urological symptoms.9,13–15 This paper aims to present an overview of the urological symptoms associated with OSA and examine their response to CPAP. Further, we review screening tools in OSA, demonstrating how urological manifestations may aid clinicians in diagnosis.

Urological manifestations of OSA

Nocturnal polyuria

NP is defined as nocturnal urine production representing >20–30% of the total voided volume over 24 hours.16 Diagnosis of NP requires 24-hour urine collection, so some researchers opt for the number of nocturia events as a proxy for NP. The prevalence of nocturia is reported to be 29%; however, it varies with age.17 In OSA, the prevalence of nocturia in people aged >45 years is reported to be 44–68%.18 A meta-analysis that included 406 patients with OSA and 9518 controls reported a significant correlation between the severity of OSA and presence of nocturia, suggesting nocturia could be an indication of severe OSA.19

Overactive bladder

OAB is defined as urinary urgency, usually with urinary frequency and nocturia with or without urinary incontinence.16 In the general population, the prevalence of OAB has been reported to be approximately 12%, compared with 61–78% in those with OSA.9,20 Multiple studies using polysomnography (PSG) have significantly associated OAB with OSA.9,21 In one overnight study of 38 patients with OSA, Yilmaz et al found that saturations ≤90% correlated with urgency symptoms.21 Similarly, Guzelsoy et al identified that the number of hypoxic events below 90% and the time spent hypoxic under 90% were significantly associated with OAB in OSA.9

Erectile dysfunction

ED is the consistent inability to achieve or maintain a penile erection long enough to have satisfactory sexual intercourse.22 The prevalence of ED varies significantly depending on age, ranging from 3% to 76%.23 However, in a recent longitudinal study of 17,785 people with sleep disorders and 35,570 controls, the prevalence of ED was reported to be 9.44-fold higher in patients with OSA.22 Other studies have also identified a strong association between OSA and ED. For instance, a study of 502 men using PSG identified OSA as a risk factor for ED as determined by an aggregate score, which incorporated the number, duration and severity of hypoxic events overnight.11 Similarly, a cross-sectional study of 401 men using PSG reported mean overnight hypoxaemia in OSA patients is an independent risk factor for ED.24

Pathophysiology

Although the pathophysiology of the urological manifestations of OSA is still being investigated, overnight chronic intermittent hypoxia is commonly identified as a significant variable. Nocturia, for example, is hypothesised to be related to pulmonary artery constriction, which occurs secondary to hypoxia in the lungs, leading to an increase in right atrial pressure. This, in turn, triggers the release of atrial natriuretic peptide, resulting in natriuresis overnight.25 Chronic intermittent hypoxia is hypothesised to contribute to OAB and ED through peripheral nerve damage.8 This is supported by Lüdemann et al, who reported hypoxia under 90% in OSA correlated with axonal damage in peripheral nerves.26

OSA therapy and its effects on urological manifestations

OSA therapy

According to Australian data, 42% of people with OSA use CPAP.1 Although CPAP is recommended treatment in OSA, its potential to impact cardiovascular outcomes and mortality is under investigation.27 In 2019, the Australasian Sleep Society published a consensus opinion from an expert panel regarding OSA treatment benefits, reporting that moderate-to-severe OSA treatment data have yet to conclusively establish a positive impact on long-term cardiovascular risk.28 However, in 2021, a meta-analysis was published that reported CPAP was associated with reductions in cardiovascular events and all-cause death, although these benefits were significantly reduced if CPAP was used for less than four hours per night.12 Among Australian CPAP users, 31% use it for four or more hours per night and the Australasian Sleep Society noted some randomised control trials report an average of three hours of CPAP per night.1,28 Conversely, the Australasian Sleep Society highlighted that patients who tolerate four or more hours of CPAP may be more adherent to treatment of their other cardiovascular comorbidities.28 Although CPAP’s impact on cardiovascular outcomes remains to be debated, observational data indicate that it may provide symptomatic relief of urological symptoms in OSA.29–31

NP, OAB and ED response to OSA therapy

The evidence for the response of urological manifestations of OSA to CPAP therapy in OSA stems from prospective studies and a few meta-analyses (Table 1). Using urodynamic studies, PSG and surveys, multiple groups have reported improvements in NP, OAB and ED after CPAP therapy.14,15,29–34 Moreover, these benefits were observed to persist even at one year after initiating CPAP.14,32,34 Although a recent Cochrane review has indicated that treating OSA may improve ED, the quality of the data supporting this claim is low, and poor reporting of CPAP adherence is prevalent across CPAP research in general.13 Given that CPAP adherence can significantly influence treatment outcomes, it is crucial for future OSA research to include adherence reporting.1,12

| Table 1. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment in obstructive sleep apnoea on urological symptoms |

| |

Study type |

Study length |

Methodology |

No. participants |

Statistically significant findings |

| Nocturnal polyuria/nocturia |

| Coban et al 202029 |

Prospective |

3 months |

Urodynamic studies

Questionnaire |

54 |

Reduction of nocturia episodes |

| Vrooman et al 202032 |

Prospective |

1 year |

Questionnaire |

274 |

Reduction of nocturia by one or more void per night |

| Fernández-Pello et al 201914 |

Prospective |

1 year |

Urodynamic studies

Questionnaire |

43 |

Reduction of nocturia by one void per night |

| İrer et al 201833 |

Prospective |

3 months |

Polysomnography

Questionnaire |

104 patients

22 controls |

Reduction of nocturia episodes |

| Wang et al 201530 |

Meta-analysis |

1–12 months |

Polysomnography

Questionnaires |

307 |

Reduction of nocturia by two voids per night

Reduction in night-time urine production |

| Overactive bladder symptoms |

| Fernández-Pello S et al 201914 |

Prospective |

1 year |

Uroflowmetry studies

Questionnaire |

43 |

Improved scores on OAB questionnaire |

| Dinç et al 201831 |

Prospective |

3 months |

Polysomnography

Questionnaire |

73 |

Improved scores on OAB questionnaire |

| İrer et al 201833 |

Prospective |

3 months |

Polysomnography

Questionnaire |

104 patients

22 controls |

Improved scores on OAB questionnaire |

| Erectile dysfunction |

| Yang et al 202115 |

Meta-analysis |

1–3 months |

Questionnaire |

206 |

Improved scores on ED questionnaires |

| Coban et al 202029 |

Prospective |

3 months |

Urodynamic studies

Questionnaire |

54 |

Improved scores on ED questionnaires |

| Li et al 201934 |

Meta-analysis |

4 weeks– >1 year

|

Questionnaire |

138 |

CPAP improves scores on ED questionnaires but combined therapy with CPAP and PDE5i is superior to CPAP alone |

| İrer et al 201833 |

Prospective |

3 months |

Polysomnography

Questionnaire |

104 patients

22 controls |

Improved scores on ED questionnaires |

| CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ED, erectile dysfunction; OAB, overactive bladder; PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor. |

Most importantly, for patients, İrer et al assessed the impact of the urological manifestations of OSA on quality of life (QOL) and investigated whether QOL improves following CPAP treatment.33 Their study revealed that the presence of NP, OAB and ED in OSA significantly affected QOL, with the largest impacts in those with severe OSA.33 İrer et al reported that after three months of CPAP treatment, urological symptom and QOL surveys showed significant improvements.33

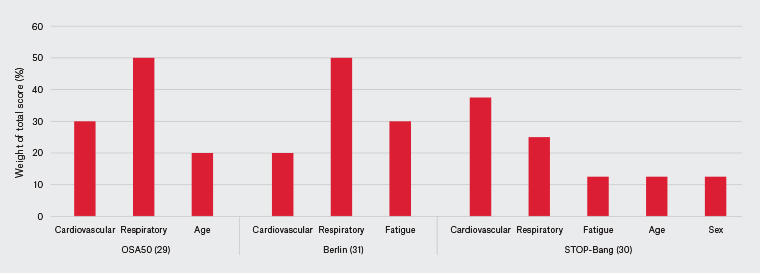

OSA screening

The screening tools in OSA commonly include the OSA50, STOP-Bang and Berlin questionnaires. These questionnaires mainly address cardiorespiratory issues (Figure 3). However, with increasing knowledge about OSA, certain patient groups may not fit into these categories and urological symptoms could serve as adjunct screening tools.

Figure 3. Obstructive sleep apnoea questionnaire risk factor representation by category.35–37 Click here to enlarge

Screening for OSA in special populations

The OSA50 has a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 31%, which is comparable to the Berlin questionnaire and STOP-Bang. However, these results vary based on variations in criteria.35–37 Although high-sensitivity screening tools are available, as previously stated, Australian data indicate that 11% of people might have undiagnosed OSA.1 This might be due to several factors, such as relying on nocturnal respiratory symptoms, cardiorespiratory-weighted screening tools and patients who present with non-classical symptoms.

In the Berlin and OSA50 questionnaires, nocturnal respiratory symptoms represent half of the total score.35,37 In 2019, 40% of Australians reported they had no current sleeping partner, making night-time observations difficult to obtain.1

Clinicians can identify the classical cardiorespiratory OSA patient, but recently multiple phenotypes for OSA have been defined, such as OSA with predominantly daytime symptoms.38 Importantly, the daytime sleepiness phenotype was associated with younger patients who had less cardiovascular comorbidities but more severe OSA. Unfortunately, in the OSA50 and STOP-Bang questionnaires, younger age is screened out and cardiovascular risk factors have a large representation.35,36,38

Finally, women present a unique challenge in OSA screening because they can have distinct symptoms compared with men.5 In a study of 6716 patients, female sex was associated with symptoms such as depression, morning headaches, nocturia and frequent awakenings overnight in OSA.5 Interestingly, a study of 1809 patients found the STOP-Bang questionnaire had a sensitivity around 50% for screening OSA in women.39 This is likely related to the STOP-Bang questionnaire scoring female sex one point less than male sex, whereas the Berlin and OSA50 do not include sex.35–37 Importantly for clinicians, female sex has been reported as a predictor of significant cardiovascular disease in OSA, so extra care must be taken when assessing for OSA.5

Screening for OSA with nocturia

Although no validated tools that incorporate urological symptoms in screening of OSA exist, Romero et al reported nocturia has clinical utility for screening OSA.40 Romero et al found that in 1006 patients, nocturia as a symptom was 85% sensitive for identifying OSA, which was on par with snoring.40 Further, with linear regression, nocturia frequency predicted OSA severity better than body mass, sex, age and self-reported snoring.40

Clinicians should be selective in their choice of screening tools, considering the potential variability in the reported sensitivities. Moreover, a positive urological history in assessment might increase the likelihood of underlying OSA and warrant specialist referral, because no screening test can replace sound clinical judgement.

Conclusion

OSA imposes a significant burden on patients and places strain on our public healthcare system in Australia. Emerging evidence has linked NP, OAB and ED with OSA. Although further research is needed to establish the long-term effects of CPAP treatment on cardiovascular outcomes, observational studies suggest that it can alleviate urological symptoms and improve QOL. Although our screening tools are useful, patients previously considered low risk for OSA might still have the disease, and the presence of urological symptoms might provide a hint to clinicians. Therefore, the presence of these difficult-to-treat symptoms should serve as a red flag to clinicians, prompting them to consider underlying OSA and further investigation or specialist referral.