In 2021, ulcerative colitis (UC) patients were estimated to account for 334 out of every 100,000 patients presenting to general practitioners (GPs) in Australia.1 A severe complication, known as acute severe UC (ASUC), is seen in up to 25% of this population and requires swift and decisive emergency care to prevent further deterioration.2 Recognising the clinical significance and the potential effects of ASUC on patient outcomes, the goal of this article is two-fold. First, it aims to equip both rural- and urban-based GPs to swiftly identify patients with ASUC. Second, this article underscores the importance of holistic patient management. This includes insights into in-hospital care regimens tailored for ASUC patients and postoperative considerations that can influence patient recovery and long-term outcomes.

Clinical features and risk stratification

From a surgical perspective, the Truelove and Witts severity criteria is the most sensitive and prevalently used for defining ASUC.3,4 A patient with ASUC typically exhibits at least six bloody motions daily and a minimum of one sign of systemic toxicity, as detailed in Table 1.4 Australian guidelines, based on the Montreal classification, stratify risk into mild (≤4 stools without blood), moderate (>4 with or without blood) and severe (≥6 stools, with blood and signs of toxicity).5 However, assessment tools such as the Mayo clinic score6 and the Montreal classification7 have limited use in a surgical setting due to a paucity of validation data.3,8 Regardless of the chosen criteria, the classification of severity requires periodic re-evaluation.

| Table 1. Symptoms and signs that encompass an acute severe ulcerative colitis diagnosis according to the Truelove and Witts criteria4 |

| Criteria |

Definition |

| Bloody stools |

>6 per day |

| Plus one of |

| Tachycardia |

Heart rate >90 beats/min |

| Pyrexia |

Core temperature >37.8°C |

| Raised inflammatory markers |

ESR >30 mm/h

CRP >30 mg/L |

| Low haemoglobin |

Hb <10.5 g/dL |

| CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Hb, haemoglobin. |

Evaluation by the treating team

The treating team’s assessment usually involves pre-treatment evaluation with biochemical and microbiological studies, diagnostic imaging, and endoscopic investigations to further define the severity and extent of the inflammation. The GP might wish to initiate investigations, where practical, particularly when specialist care is not readily available.

In addition to a routine blood panel with inflammatory markers, a blood culture should be considered in those who are febrile or display leucocytosis. A screen for opportunistic infections (ie human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C and varicella zoster), which would otherwise be masked, should be conducted in preparation for rescue pharmaco-therapy (ie infliximab or cyclosporin). Typically, rescue therapy is used as a second-line treatment when intravenous steroid therapy fails to manage the disease over a span of three to five days.9 Serum magnesium levels and lipid profiles might also be arranged in preparation for cyclosporin treatment.10 If prior tuberculosis exposure is likely, performing an interferon-gamma release assay is recommended (eg the QuantiFERON Gold test, Cellestis/Qiagen, Carnegie, Australia), along with a chest X-ray.10 When organising these investigations, the GP should take into account both the cost of testing and the patient’s immunosuppression status.

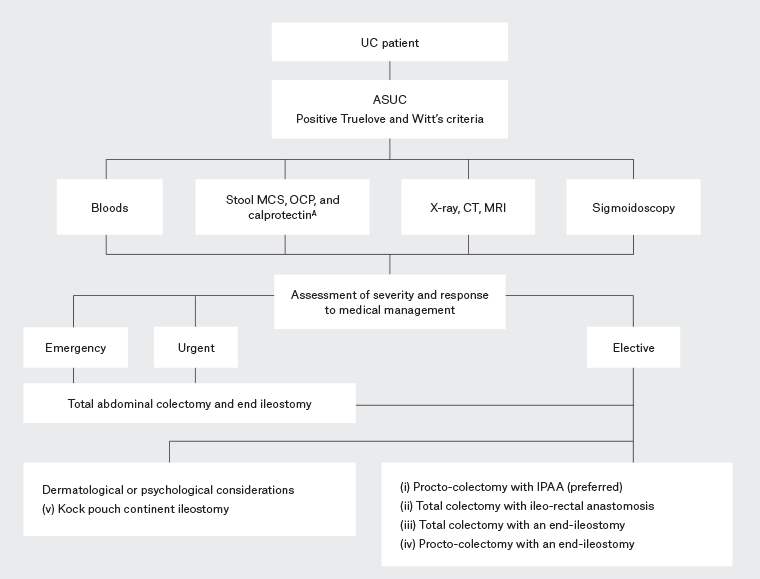

Stool testing, to exclude an infective cause, is also indicated. As shown in Figure 1, the clinician might assess for ova, cysts and parasites (OCP), viral, and bacterial infections, including Clostridium difficile toxin, with a stool microscopy, culture and sensitivity study.3,5,11 Additionally, a faecal calprotectin assay can assess disease severity; a calprotectin level >50 mcg/g might represent active inflammation.12

Figure 1. Management algorithm for patients presenting with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Click here to enlarge

APathogens tested for include Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia species, Escherichia coli, Giardia, Amoebic infections and Clostridium difficile toxin3,9,10

ASUC, acute severe ulcerative colitis; CT, computed tomography; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; MCS, microscopy, culture and sensitivity; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OCP, ova, cysts and parasites; UC, ulcerative colitis.

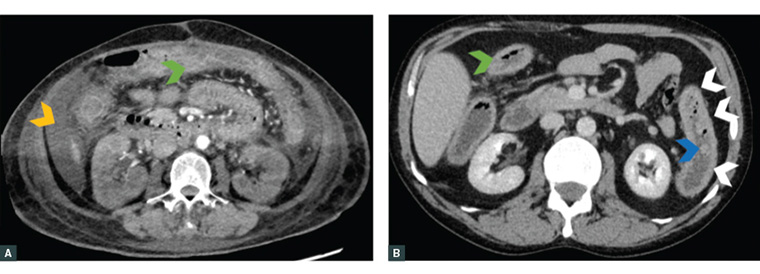

Diagnostic imaging, including abdominal radiography, is used to identify toxic megacolon. Additionally, cross-sectional imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging, is often necessary for patients who might have complications such as colonic perforation. Figure 2 provides an illustrative CT finding from an ASUC patient. For GPs with limited access to specialist input or those dealing with diagnostic ambiguity, this investigation might prove especially useful. It not only offers a direct approach to patient monitoring but also aids in risk stratification, potentially reducing specialist interventions for cases deemed low to moderate risk.

From a surgical perspective, a ‘gas-less’ and ‘prep-less’ sigmoidoscopy, a type of endoscopy commonly used in ASUC patients, aids severity assessment.13 It also facilitates prompt histological biopsies (eg for cytomegalovirus).11 It should be performed at the earliest opportunity, with various studies demonstrating improved outcomes in ASUC patients undertaking endoscopy within 72 hours of hospitalisation.13

Figure 2. A and B. Axial computed tomography images of acute severe ulcerative colitis patients requiring an operation. These images highlight bowel wall thickening (green arrowhead), loss of haustral markings (white arrowheads), pseudopolyp extending into the lumen (blue arrowhead) and free intraperitoneal fluid (orange arrowhead).

Medical management

In addition to GPs, the management of ASUC requires a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons, stoma therapists, nutritionists and psychologists. The following section summarises important components of ASUC management, with a particular focus on surgical management. Nevertheless, it would benefit the GP involved in the care of ASUC patients to have a broad understanding of their patient’s journey through secondary care.

Hydration and nutrition

Monitoring the patient’s fluid status and addressing electrolyte abnormalities are essential.9 Maintenance of enteral feeding is preferred and should be continued whenever clinically appropriate, as it might lower the risk of complications.14 In some cases, parenteral nutrition might be required.

Medications

Initial medical management includes intravenous glucocorticoids with potential escalation to a biologic agent (usually infliximab)3,11,15,16 and aims to reduce colectomy rates by up to 80%.17–20 Medications that harbour a potential risk of inducing colonic dilatation should be used cautiously (eg anticholinergics, antidiarrheals and opiates).11 Antibiotic use is also a consideration; although some small cohort studies suggest potential benefits,9 a recent randomised trial concluded that the use of antibiotics in ASUC did not improve outcomes outside a clinical context of severe sepsis.21

Venous thromboembolism risk mitigation

ASUC patients have an up to eight-fold increased risk of thromboembolism because of prolonged hospitalisation, convalescence and the systemic burden of a profound inflammatory process.15 Therefore, compression stockings and chemical thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin are usually prescribed.22 Patients aged 45 years and older, who have a hospital stay of seven days or longer, and with a previous history of C. difficile infection upon their initial admission are identified as having an increased risk for post-discharge venous thromboembolism (VTE).23,24 Yet, within the Australian context, the question remains: is there a benefit to extending VTE prophylaxis for hospitalised patients upon discharge?

Surgical urgency and indications

Emergency surgery

GPs play a crucial role in identifying individuals at risk of severe and potentially fatal complications, for whom immediate surgical intervention is indicated. Such complications encompass toxic megacolon, haematochezia paired with haemodynamic instability, and perforation. If a patient does not fit these emergent criteria, they can be further assessed and categorised into either urgent or elective surgical categories.

Urgent surgery

In ASUC patients who do not qualify for emergency surgery but need intervention during their initial hospital stay, urgent surgery is often warranted. This is especially the case for those with acute fulminant colitis (AFC) that is refractory to medical treatment.16 Symptoms of AFC include persistent bleeding, frequent bowel movements and systemic toxicity indicators such as fever.25 The Travis criteria can help predict surgical need, particularly if a patient has more than eight daily stools or three to eight stools with a C-reactive protein level above 45mg/L after three days on steroids.26

Elective surgery

ASUC patients who remain ambulatory and are managed in a GP setting might still require elective surgery.27 Common indications include the inability to wean off steroids or the presence of dysplasia.

Types of surgical intervention

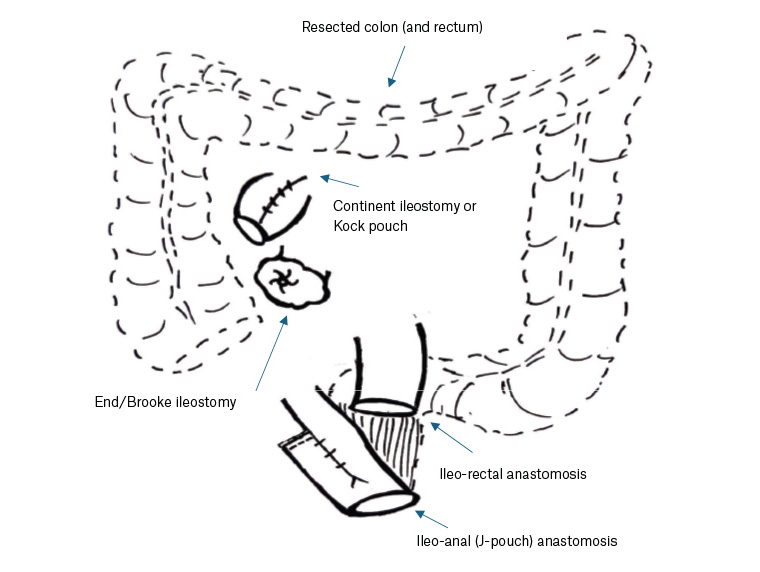

Figure 1 highlights the types of surgical intervention offered to patients in emergency, urgent and elective surgery settings, whereas Figure 3 illustrates the procedural options for ASUC patients.

Figure 3. Original diagrammatic representation of surgical options for acute severe ulcerative colitis patients.

Urgent and emergency patients typically undergo a total abdominal colectomy and end ileostomy. In contrast, elective patients are often presented with restorative techniques, most commonly an ileal pouch anal anastomosis. The decision of which procedure is performed hinges on the patient’s medical comorbidities, anal sphincter function, aspiration to optimise fecundity, capability to manage a stoma, extent of lingering disease and specific colitis diagnosis (ie UC versus Crohn’s or indeterminate colitis).27 Table 2 summarises how these unique scenarios can influence the choice of surgery.

| Table 2. Surgical indications in various special circumstances |

| Special circumstance |

Recommended treatment |

| Medically comorbid |

Proctocolectomy with end ileostomy as low complication and reduced operating time |

| Risk of faecal incontinence due to impaired anal sphincter function |

Proctocolectomy with end ileostomy

Consideration of ileorectal anastomosis if significant quality of life expected with stoma |

| Preserving fertility and sexual function |

Total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis or IPAA after family is complete |

| Indeterminate colitis (10–15% of patients)19 |

Complex – some might perform total colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis |

| Crohn’s colitis |

Segmental colectomy, total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy, and proctectomy |

| IPAA, ileal pouch anal anastomosis. |

Postoperative complications

GPs have several factors to consider in the postoperative phase. They should conduct regular follow-ups to monitor wound healing, assess bowel function and identify potential complications. They should ensure that patients receive adequate nutritional sustenance for recovery while also adhering to any dietary guidelines or restrictions.

GPs should have an understanding of postoperative complications that can arise, including bowel obstruction, stricture of the anal canal or anastomosis, pelvic sepsis, pouch failure and faecal incontinence. Indeed, the GP might be the first clinician a patient presents to with postoperative complaints. Furthermore, issues relating to the development of dysplasia or cancer in the pouch, sexual dysfunction and fertility also demand a GP’s awareness and proactive management.27,28

For rural GPs, having this knowledge is particularly advantageous. It allows for early identification and management of complications, empowers handover of care by the GP and provides guidance as to which patients require timely care in areas where specialised medical resources might be limited.

Surgical complications

Depending on the specific type of surgery the patient has undergone, various surgical complications might be encountered. GPs might identify an anastomotic stricture, occurring in 4–16% of cases, during a per rectal examination. This condition, presenting with difficulty in stool passage or obstipation, might necessitate trans-anal or endoscopic dilatation and, in certain instances, reoperation.28–30 If a patient exhibits symptoms of bowel obstruction (2–4%), GPs should prioritise cross-sectional imaging and promptly refer to the surgical team.28 GPs should be vigilant for signs of pelvic sepsis and pouch failure, found in 8.5–9.5% of patients.31 Immediate referral to the emergency department is vital for patients showing infective symptoms, heightened faecal frequency (ie more than four to six bowel motions a day), loose stools or symptoms of obstruction. Additionally, the potential for dysplasia or cancer in the remaining rectum (if present), anal transitional zone or ileal pouch underscores the need for GP referral for endoscopic surveillance.32–34

Urogenital complications

Faecal incontinence and overnight incontinence are common symptoms in patients who have undergone pouch surgery (53–76%), with patients presenting with an average of six daily stools or an overnight stool.35 For male patients, sexual dysfunction might manifest as impotence (1.5%) or retrograde ejaculation (4%).36 In female patients, while some might temporarily grapple with dyspareunia (7%), their frequency of intercourse and capacity to achieve orgasm usually remain unchanged.27 GPs should be aware that in the context of fertility, approximately 88% of female patients who have undergone a surgical intervention and hoping to conceive have successfully given birth.37 However, guidance on the optimal mode of delivery continues to be a subject of discussion and study.38,39

Allied health

Stomal therapist

A poorly positioned stoma can adversely affect the patient’s quality of life, but a skilled stomal therapist can employ a range of troubleshooting techniques to mitigate such issues. This process not only improves surgical precision but also cultivates a meaningful rapport between the therapist and the patient, fostering trust and facilitating better outpatient care.

Psychological support

GPs should recognise their pivotal role in providing psychological support and counselling in these patients. Given the disease’s chronic trajectory, its toll on quality of life and the looming possibility of surgical intervention, many patients suffer mood disturbance and require a GP’s holistic and continuous care. Addressing psychological factors can also aid in patients’ overall capacity to manage complex treatment regimens.

Conclusion

The role of a GP in managing ASUC encompasses early identification of affected patients and ensuring their swift transition to emergency care. Furthermore, diligent postoperative follow-ups are essential, empowering GPs to detect patients susceptible to urogenital, psychological or surgical complications. GPs are pivotal in orchestrating comprehensive care in collaboration with allied health professionals. By deepening their understanding of ASUC’s signs, symptoms and management protocols, GPs can markedly enhance the prognosis for this vulnerable group of patients and ensure timely intervention.

Key points

- ASUC is a complication experienced by 25% of patients with UC.

- GPs play a crucial role in identifying and promptly referring patients with this complication, collaborating with the treating team, educating the patient and coordinating postoperative care.

- Serial examination and assessment of vital signs, laboratory tests, and monitoring of stool frequency and consistency are essential to evaluate severity and treatment response.

- GPs might facilitate surgical referral in patients who fail medical management or experience complications.

- Surgical intervention can be classified as emergency, urgent or elective depending on the severity of presentation.