With the welcome enhanced awareness of endometriosis in our community has come the expectation that all pain can be ‘seen’ at laparoscopy. There is the anticipation that a laparoscopy will find and remove endometriosis lesions and patients’ pain symptoms will be cured. Any self-doubt or disbelief from family, friends or health practitioners will be shown as misplaced. Their suffering will be validated, and support will be forthcoming. Unsurprisingly, where the expectation that ‘real’ pain will be visible has been perpetuated, your patient might be sorely disappointed and embarrassed when their laparoscopy shows a normal, healthy and likely fertile pelvis. Anxiety and embarrassment are frequent emotions when in fact a normal pelvis is always the best outcome.

This requirement that female pelvic pain should be visible is a high and unfair ‘proof of pain’ bar that is not applied to most other pain conditions. For example, it is generally accepted that a migraine is painful, yet we do not require migraine sufferers to have visible brain lesions to verify that their pains are real.

The visual confirmation of a healthy-looking pelvis can be celebrated by a patient where she understands that not all pain can be seen at surgery and that her practitioner will continue to work with her to manage her pain. Support will continue, and she is no less deserving of care than women with endometriosis present.

So, where to now? What’s happening? Why does she have pain?

To explain this, the concepts around chronic pelvic pain require reframing.

This article outlines a practical general practice-based approach to the care of patients assigned female at birth: girls, women and non-binary and trans individuals.

An approach to management of pelvic pain syndrome

This article describes a symptom-based approach suited to general practice that considers pelvic pain as, first, a pain syndrome with multiple symptoms and, second, a condition where endometriosis is commonly found but need not be present. In this context, there need be no distress where a laparoscopy shows no lesions. The absence of findings means that she is now less likely to require further surgery. The non-surgical management of her pain and pain-related symptoms that is required for all types of chronic pelvic pain continues.

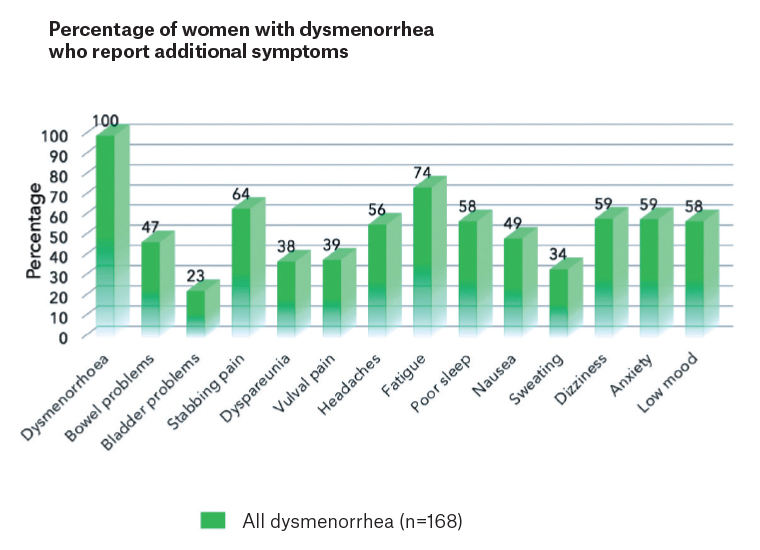

Pelvic pain syndrome includes a wide range of symptoms both within and outside the pelvis that cluster together. Figure 1 describes the typical symptoms occurring with dysmenorrhoea.1 Like all syndromes, none of the symptoms are essential for a diagnosis, but they are all more common among this group than the general community. These symptoms can be divided into four categories: pain from pelvic organs with or without endometriosis; pain from pelvic muscles; pain generated in the central nervous system (CNS); and additional psychosocial factors, including early adverse life events and psychosocial stress. Endometriosis, if present, adds another significant layer of complexity to pain and fertility management but is not essential. Where this approach has been explained before laparoscopy, there is no need for patient distress following negative findings. This approach involves gynaecologists and allied health practitioners where their skill sets are required but is predominantly a general practitioner-centric model. It provides a matrix for symptom management and reduces stress on both sides of the consultation desk. Taking a history is facilitated by use of the pelvic pain questionnaire available through the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia (www.pelvicpain.org.au).

Figure 1. The range of symptoms that cluster with dysmenorrhoea in women with pelvic pain.

Figure 1. The range of symptoms that cluster with dysmenorrhoea in women with pelvic pain.

Reproduced with permission from Evans et al.1

Pain from pelvic organs with or without endometriosis

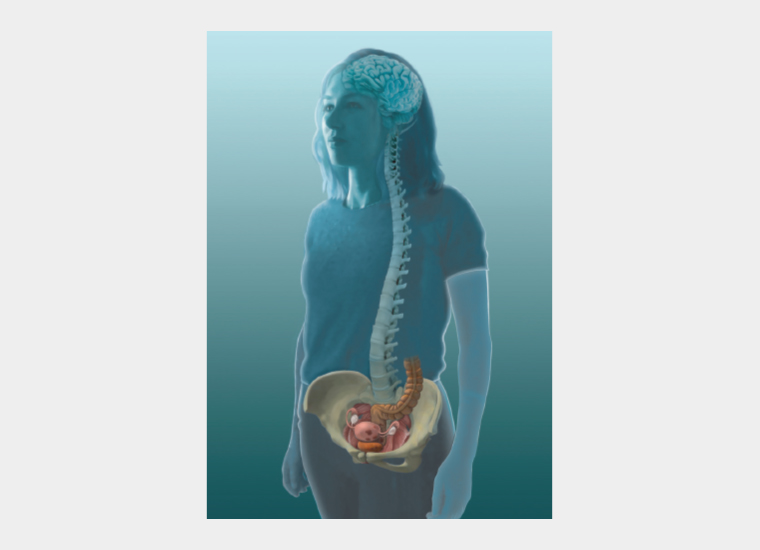

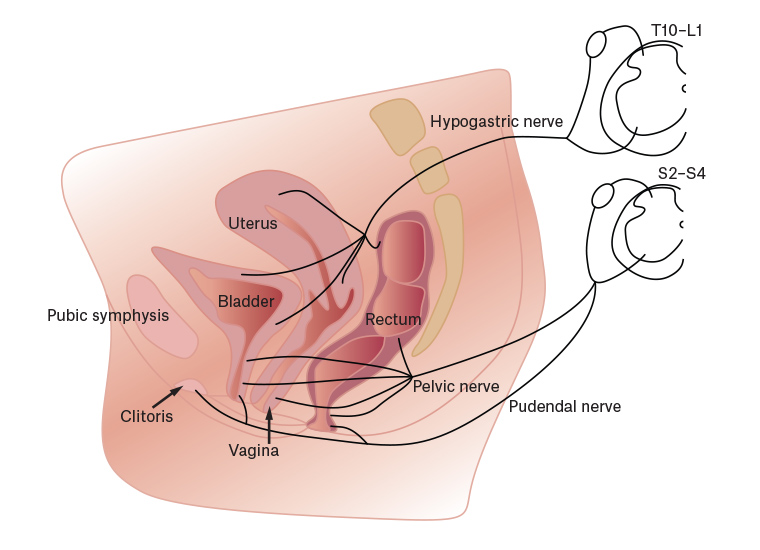

A common life scenario involves a girl who was generally well until puberty. Dysmenorrhoea begins at or soon after menarche, and initially she is well between periods. After a variable amount of time,2 pain becomes more complex in a proportion of patients with dysmenorrhoea. Additional pelvic organs become symptomatic and join the uterus as pain drivers of her individual manifestation of pelvic pain syndrome (Figure 2). The shared dermatomes, adjacent ascending spinothalamic tracts and pelvic muscle associations mean that sensations originating in any one of these organs might feel similar (Figure 3), making it difficult for women to differentiate the cause of pain during pain flares.3

Figure 2. The pelvic organs, with or without endometriosis, commonly involved in chronic pelvic pain.

Reproduced with permission from Dr Susan F Evans P/L.

Figure 3. The shared sensory innervation of the pelvic organs via the hypogastric nerve to similar spinal segments.

Figure 3. The shared sensory innervation of the pelvic organs via the hypogastric nerve to similar spinal segments.

Reproduced with permission from Professor P Jobling.

Useful questions

a. Did you have bladder or bowel problems when you were a child before your periods started?

b. What were your periods like as a teenager?

c. Do you have any bowel or bladder problems now?

These questions help determine which of the pelvic organs have been involved in initiating and driving the overall chronic pelvic pain picture.

Management plan

This approach aims to reduce stimuli from each symptomatic organ in the pelvis. Dysmenorrhoea provides a stimulus to persistent pelvic pain with every menstrual period, and prolonged vaginal bleeding will provide a prolonged stimulus.

Where dysmenorrhoea has been a major pain driver, of both pelvic muscle pain and central pain sensitisation, then menstrual suppression will both avoid uterine pain and reduce the stimulus to pelvic muscle spasm (often described as the worst pains) and the CNS (where many of the feel bad symptoms are generated). While this has commonly been achieved with the oral contraceptive pill, a continuous progestogen such as norethisterone 5 mg or dienogest 2 mg might be more effective at reducing symptoms. A levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device is best inserted after hormonal suppression has thinned the endometrium for 2–3 months and after pelvic muscle hypertonus and central pain sensitisation issues have been reduced. A diclofenac suppository (100 mg or 50 mg if sensitive) is useful for flares when bleeding or overnight during periods. Tranexamic acid to reduce menstrual bleeding might also be beneficial.4

Over time, it is common for the bowel and sometimes the bladder to also become symptomatic, presenting as constipation, food intolerances or urinary tract infection-like episodes with negative urine culture. The aching, stabbing pelvic muscle pains of pelvic muscle pain might co-exist and worsen when bowel symptoms flare. Your patient has more to gain from a good diet and soft bowel action than other women and more to lose from a poor diet. The management of bowel and bladder pain symptoms is outlined in Endometriosis and pelvic pain,5 and referral to a gastroenterologist or urologist might be required in a small proportion of cases.

Pain from pelvic muscles

Pain from pelvic muscle hypertonus is frequently overlooked yet often described as the worst pain among a patient’s many symptoms (Figure 4). Inflammation in a pelvic organ can induce inflammation in the CNS, causing increased tension in the pelvic muscles. During a flare, a worsening of pelvic muscle hypertonus can result in pelvic muscle spasm with severe pain. Effectively, the patient is having a muscle cramp inside the pelvis during flares. Commonly involved muscles are the muscles of the pelvic floor and lower anterior abdominal wall, the obturator internus bilaterally and the gluteus medius.

Figure 4. The pelvic muscles commonly found to be hypertonic in patients with pelvic pain: puborectalis and obturator internus.

Reproduced with permission from Dr Susan F Evans P/L.

Useful questions

a. What does the pain feel like?

An aching or stabbing pain on one or both sides of the pelvis that is affected by position or movement, better with a heat pack or hot bath, makes it difficult to walk and feels best when curled up in a ball usually reflects pain in the obturator internus, the strong muscle on the sides of the pelvis that controls the hip joint. An ultrasound probe will cause pain when it presses laterally, and pain often radiates to the back, to the hip or down the front of the leg. One finger vaginal examination palpating laterally to the obturator internus, with the patient’s knee pressed out against the practitioner’s outside hand, will find the tender muscle and confirm the diagnosis.6 Stabbing pain up the rectum or vagina with pain during intercourse, with tampons or with defecation often represents high muscle tone in the pelvic floor muscles. There might be incomplete bladder emptying due to pelvic floor muscle contraction and pain might persist to the next day after intercourse. Observation of contraction and relaxation of the vaginal introitus will reveal that the muscle is tight and the vaginal introitus is relatively closed.

b. When do you get these pains?

These pelvic muscle pains will worsen whenever one of the pelvic organ pain drivers is active. For example, during a period, she might describe pain from uterine cramps centrally but also stabbing pain from the obturator internus. She might recognise that she experiences similar pain when constipated.

Management plan

Education on the role of pelvic muscles in the patient’s pain experience is valuable, reassuring and beneficial. The pain is severe, but she need not fear that it is dangerous. Frequently, women reflect that the aching, stabbing pain has been present from early years, often attributed to other causes. She might also reveal that surgical procedures were undertaken for this pain, while the actual cause of pain was not recognised.

Management includes keeping moving, specific stretches, pelvic physiotherapy with a physiotherapist who offers muscle down training, review to ensure the patient’s current activities are not aggravators, pelvic muscle relaxation and management of the particular pelvic organ driving the pelvic muscle pain. A walk each day and a focus on movement and muscle relaxation rather than strenuous exercise and muscle tightening is a great start. While a laparoscopy involves muscle relaxant as part of the procedure, which might contribute to short-term relief of pelvic muscle spasm, pelvic muscle hypertonus recurs where not specifically treated. The occasional use of a diazepam suppository (5 mg compounded in a fatty base) used per rectum or per vagina can reduce pelvic muscle pain during flares. Botulinum toxin injections provide 3–6 months of relief, where available.7 However, these injections are most effective when other aspects of the pain, including the initial pain driver and the pain sensitisation, have been fully managed. Further information on stretches and a pelvic muscle relaxation audio download are available at www.pelvicpain.org.au.

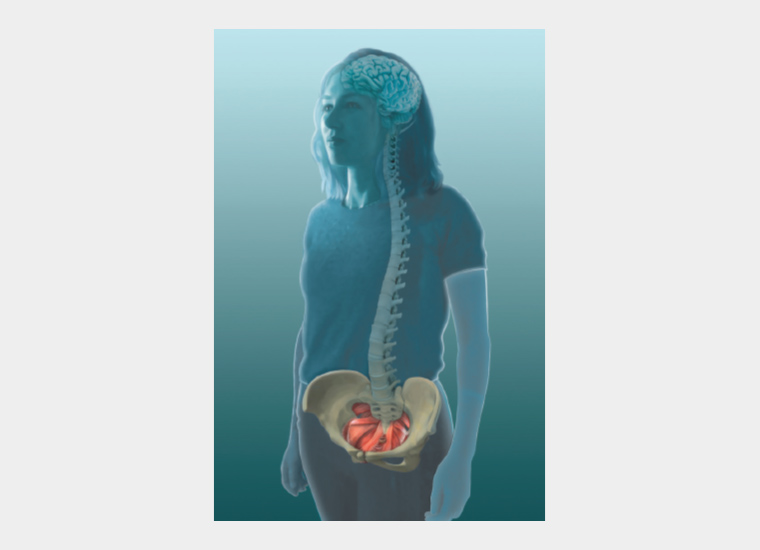

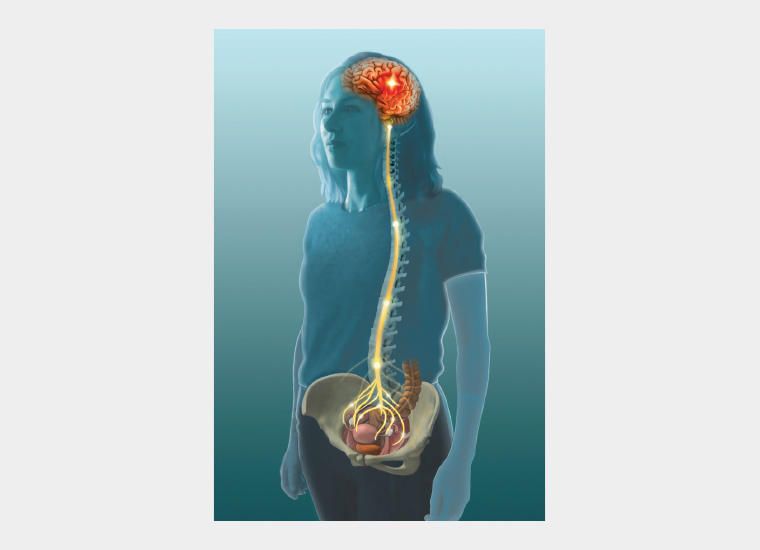

Pain generated in the central nervous system

The presence of persistent pain has been extensively linked to inflammation and neuroglial changes in the CNS (Figure 5).8,9 Asking your patient to complete a pain body map such as the map included on the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia questionnaire (www.pelvicpain.org.au) will allow you to better understand the relative balance between these two factors. Where pain is purely pelvic, managing pelvic issues alone might be sufficient. This might be the situation in the early years where dysmenorrhoea alone is her concern. Where pain is widespread, there are multiple autonomic symptoms and pain is present on most days, managing pelvic issues only is rarely sufficient. Surgical treatments, including hysterectomy, are much less likely to resolve pain in this situation.10 CNS-generated pain sensitivity is a major part of her pain and requires management. This might be the situation in women with pain on most days, fibromyalgia-like symptoms, fatigue, anxiety, low mood, poor sleep, nausea, dizziness, fainting, headaches or poor cognition.

Figure 5. Enhanced activation of the central nervous system present in patients with pelvic pain.

Reproduced with permission from Dr Susan F Evans P/L.

Useful questions

a. How many days per month do you have pain or discomfort?

b. Do you have fatigue, poor sleep, nausea, anxiety, low mood, dizziness, brain fog, headaches or difficulty concentrating?

Where pain is present on most days or these additional symptoms are present, a relatively larger central than peripheral component of the patient’s pain is present.

Management involves pain education that explains the wide range of systems involved and that surgical options, including hysterectomy, might be less effective strategies. Useful strategies include maintaining purposeful activity in life, physical activity, pain psychology and pain medications. Amitriptyline in low dose (5–25 mg early evening) is the most effective of the medications,11 particularly as it also reduces headache and improves sleep. Duloxetine at 30–60 mg in the morning is particularly effective with higher levels of central pain sensitivity and where anxiety or low mood are present. Gabapentin and pregabalin have low effectiveness in most cases of dysmenorrhoea-related pain.12 A pain psychologist might be invaluable. The purpose of the consultation is to address how psychological factors affect their approach to chronic pain. The combination of pelvic organ and CNS pain is called nociplastic pain and multi-symptom pain conditions are sometimes referred to as chronic overlapping pain syndromes.

Importantly, CNS-generated pain can be induced or worsened by regular use of opioids. It is imperative that the first practitioner to prescribe regular opioids understands the heavy burden of responsibility that they take on when writing the first prescription for regular opioid use. There is increasing evidence that the changes in the spinal cord induced by regular opioids are not fully reversible.

Aggravating factors

Early adverse life events, psychosocial stress, sleep deprivation, physical inactivity and a lack of life purpose will all contribute to the severity and life impacts of pain.

Conclusion

From a health practitioner’s perspective, caring for patients with so many symptoms, especially where there is co-existent societal, educational and financial disadvantage, can be daunting. None of us leave our training programs with all the skills required to manage all these symptoms. However,

with a little upskilling and support, becoming an effective practitioner for women with pelvic pain is enormously satisfying.

This article has provided a framework for the assessment and management of pelvic pain where laparoscopic findings are normal. It divides the symptoms into four components: pain from pelvic organs, pain from pelvic muscles, pain generated in the CNS and additional psychosocial adverse life events.

Most of these patients are young with a full life ahead of them, especially where pain education and symptom management are successfully combined.

Key points

- Patients might feel embarrassed or distressed when laparoscopy findings are normal.

- A diagnosis of pelvic pain syndrome does not require endometriosis to be present.

- Pain from pelvic muscle spasm is a frequent cause of emergency department presentation.

- A CNS component is present in pain present for more than 3–6 months.

- A structured approach to diagnosis and management reduces stress for patients and clinicians.