One study suggests that around 14% of Australian women report having experienced painful sex (dyspareunia) in the previous 12 months.1 One of the leading causes of dyspareunia is vaginismus. Vaginismus is defined as ‘persistent or recurrent difficulties of the woman to allow vaginal entry of a penis, a finger, and/or any object, despite the woman’s expressed wish to do so’.2 Clinically, people with vaginismus often present with varying degrees of increased pelvic floor muscle tone and involuntary contractions of the pelvic floor muscles, which make vaginal penetration difficult, painful or impossible.3 As a result, people will avoid opportunities of vaginal penetration due to the pain or the associated fear and anxiety in anticipation of pain.3

A dynamic definition

The definition of vaginismus has been a topic of debate in recent years. As of 2013, the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth edition) merged vaginismus and dyspareunia into a new title of ‘genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder’ (GPPPD).4 This change has received considerable criticism because it prevents the differentiation of vaginismus from other conditions associated with dyspareunia, such as provoked vestibulodynia (pain at the entrance to the vagina, elicited by touch or pressure, in the absence of any identifiable pathology).5 Regardless, making a diagnosis for people presenting with symptoms suggestive of GPPPD – whether dyspareunia, vaginismus or both – is essential because these patients often report feeling unheard or dismissed by health professionals.6

Changing definitions make it difficult to reliably estimate the prevalence of vaginismus. Estimating the prevalence of vaginismus is also made difficult by the stigma and shame attached to sex and sexual difficulties.7 As a result of these difficulties, no methodologically and epidemiologically sound prevalence estimates are available, although it is generally reported to affect somewhere between 1% and 6% of the general population.8

Aetiology

Currently, there is no defined aetiology for vaginismus. Most researchers and clinicians agree that vaginismus is a psychophysiological problem involving cognitive, behavioural and physiological factors.

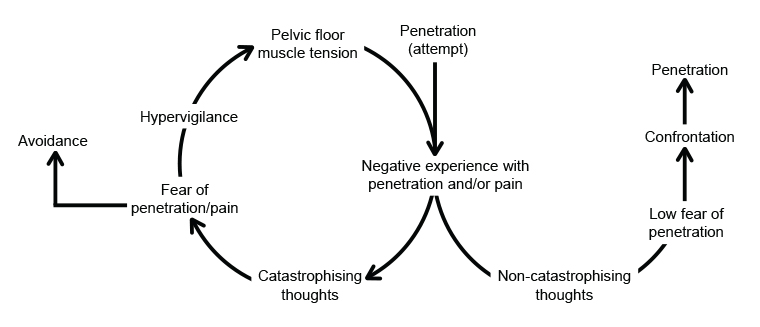

The fear-avoidance model of pain9 is often used to conceptualise the development and maintenance of vaginismus (Figure 1).10 The model outlines how a negative experience with penetration can lead to catastrophic thinking and resultant fear of penetration. This gives rise to two options: one, to avoid all activities relating to vaginal penetration or, two, to become hypervigilant to stimuli associated with penetration. Hypervigilance can lead to exaggerated defensive pelvic muscle contractions, making it difficult to achieve penetration during a subsequent attempt. An inability to achieve penetration might result in more pain and confirm negative experiences associated with penetration. In this way, the experience of vaginismus is then exacerbated and perpetuated in a vicious cycle.

Figure 1. The fear avoidance model of vaginismus.

The fear-avoidance model of pain can also be used to conceptualise recovery from vaginismus. Where someone has had a negative experience or experiences with penetration, many treatments are aimed at helping the person to understand and accept this experience to avoid catastrophising. With this understanding and acceptance, the result can be reduced fear and ultimately re-engagement with the painful or confronting experience of penetration without exaggerated defensive pelvic muscle contractions, allowing for pain-free penetration to occur. Treatment options to aid in a person’s recovery from vaginismus are covered later in this article.

Who gets vaginismus?

While the exact aetiology of vaginismus is unknown, several predisposing factors have been identified. Given that vaginismus is associated with a fear response, explicit and implicit sociocultural attitudes play a major role in predisposing someone to developing vaginismus.7

Explicit, negative sex-related cognitions often arise after a person experiences a painful or traumatic event, such as a painful gynaecological examination or sexual trauma. Where someone has not had an explicit painful or negative penetration-related event, their implicit sex-related cognitions might contribute to the development and maintenance of vaginismus.

Sex-related cognitions are embedded through an individual’s sociocultural context, including their family, friends and religious beliefs.11 People with vaginismus have consistently reported negative sex-related cognitions developing from a sociocultural context, in particular being brought up in a family where sex was not discussed, sex education was not provided and sex was seen as wrong and sinful.7 Societies where sex is taboo and female sexuality is repressed have higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction, including vaginismus.12 Implicit sex-related cognitions have a direct influence on the pelvic floor: people with vaginismus have higher levels of disgust and greater pelvic floor muscle contraction in response to sex-related images and videos than healthy controls.13 This finding highlights how a wide range of sex-related cognitions might directly affect a person’s experience with vaginismus.

Making a diagnosis

Diagnosing vaginismus can be challenging, particularly as people will often present with concomitant vulva, pelvic floor and pelvic pain.14

In a clinical setting, people presenting with symptoms suggestive of vaginismus require thorough investigation to make a differential diagnosis and rule out organic comorbidities. First, a detailed medical, psychosocial, relationship and sexual history is required, as outlined in Table 1. A thorough history will help to identify relevant aetiological and contributing factors and assist with making a differential diagnosis.

| Table 1. Recommended history-taking questions for people with suspected vaginismus |

Pain-specific questions

- Location of pain – superficial or deep, vulva or vagina

- Onset of pain – before, with or after penetration

- Is penetration possible at all?

- Can they insert fingers or a tampon?

- Intensity of pain

- Descriptors of pain – burning, aching, itching

- Chronology of pain – if multiple pain sites, what order did they develop?

- Has it been lifelong or acquired?

- What treatments have been trialled?

|

Medical history

- Other vaginal symptoms, including discharge, burning and itching

- Comorbid gynaecological conditions, including endometriosis, fibroids and other conditions associated with persistent pelvic pain

- Concurrent bladder or bowel symptoms

- History of sexually transmitted diseases

- Any obstetric delivery history of lacerations, episiotomies or other trauma

- History of abdominal or genitourinary surgery or radiation

- History of skin disorders such as eczema, psoriasis or other dermatitis

- Current contraception use

- Current medications: alternative, prescribed, over the counter

- Alcohol and drug use

|

Psychosocial context

- Patient’s view of the problem and contributing factors

- Has the problem been present in other relationships?

- Willingness of partner(s) to discuss the problem

- History of sexual or physical abuse

- Life stressor contributing factors

- Comorbid depression or anxiety disorders

- Patient goals and what they would consider a satisfactory treatment outcome

|

Relationship/sexual history

- Relationship status

- Are they sexually active?

- Other sexual dysfunctions, such as arousal, lubrication or orgasmic difficulties

- Are they able to become aroused and climax at all?

- History of traumatic sexual experience

- History of traumatic genital examination

- Level of anxiety at the thought of penetration

- Level of anxiety at the thought of a genital examination

- What is it about the examination that makes them anxious?

|

| Adapted from Heim (2001)15 and Crowley et al (2009).16 |

A genital examination is also required to make a differential diagnosis of vaginismus. A visual inspection of the vulva might indicate fissures, ulcerations, atrophy, fungal infections or other superficial skin issues, such as genital warts or herpes simplex virus. External swabs or low vaginal swabs to assess for other possible pathologies are indicated. A cotton tip should then be used to assess pain with touch or light pressure around the vestibule to assess for provoked vestibulodynia.

A single-digit vaginal examination might be useful to assess the pelvic floor muscles.17 Palpating slowly through 360 degrees will allow for an assessment of pelvic floor tenderness or tightness. The patient should be observed carefully during the examination. Signs of anxiety or distress such as gluteal tightening, elevation of the buttocks off the table or toe curling are indications that the examination should cease.18 In these patients, a speculum examination should not be performed until therapeutic interventions have been trialled to manage symptoms.

Clinical implications

Given that people with vaginismus and pelvic pain more broadly often report feeling unheard or dismissed by health professionals,6 the first step in encountering these patients in a clinical situation should be validation – that their pain is real, they are believed and the pain is not all in their head. Validation is an important step in building a strong therapeutic alliance, which has been shown to positively influence how and when people with vaginismus seek treatment.19

Speculum examination can be challenging in people with vaginismus. While symptoms of vaginismus do not necessitate a speculum examination, people might present for a procedure requiring speculum examination (eg colposcopy) and have concomitant vaginismus. People without vaginismus report feeling anxious prior to speculum examination.20 Therefore, it is not surprising that anxiety surrounding speculum examination is heightened in people with vaginismus. A thorough explanation of the procedure and the rationale for why speculum examination is required might help to ease anxiety.21 The level of discomfort experienced during digital examination might indicate whether a speculum examination will be possible. If so, the smallest speculum that still allows for optimal visualisation should be used along with water-based lubricant applied to the outer, inferior bill of the speculum.21 A patient-chosen chaperone might also help to reduce anxiety and discomfort with the procedure. Where a speculum examination becomes painful, the procedure should be stopped immediately and the speculum removed. The patient should be informed that the procedure can be tried again on another day, after vaginismus treatment options have been explored.

Patient positioning during speculum examination might make the procedure more tolerable. Given that activation of the gluteal muscles results in synergistic pelvic floor muscle activation,22 it is important that the legs are well supported during the procedure to avoid gluteal, and subsequent pelvic floor, muscle activation. One way to achieve this is to have the examination table alongside the wall where the patient can rest the outer edge of one knee on the wall and the outer edge of the other knee is supported by the chaperone or another health professional. Alternatively, the Sims position (lateral recumbent) with the use of a small Sims speculum is often well tolerated and can result in a successful speculum examination in people with vaginismus.

Treatment options

The latest clinical practice guideline on female sexual dysfunction recommends an individualised, multidisciplinary approach for vaginismus, tailored according to an individual’s underlying contributing factors and any existing comorbidities.23 This section will focus on the treatment of vaginismus as a sole diagnosis, and management might differ where other comorbidities exist (eg vulvodynia or vulvovaginal candidiasis). When vaginismus is considered through the fear-avoidance model of pain, the importance of a multidisciplinary approach is evident. Physical interventions are required to address the contributions of the pelvic floor muscles to decrease pain with penetration, and psychosexual interventions are required to address accompanying catastrophising thoughts and fear around penetration. Relevant health professionals involved in managing vaginismus might include general practitioners (GPs), sexual counsellors, clinical psychologists, physical therapists, pain specialists and gynaecologists. Table 2 outlines the current treatment options for vaginismus and the level of supporting evidence for each treatment. In most cases, successful treatment of vaginismus occurs with a combination of patient education, pelvic floor muscle relaxation, use of vaginal trainers and psychological therapy.

| Table 2. Treatment options and level of supporting evidence for vaginismus |

| Treatment |

Description |

Level of evidenceA |

| Patient education |

Education about vaginismus, vulvovaginal anatomy and pelvic floor anatomy can help people understand the underlying mechanisms and contributing factors to their experience |

IIB,24 |

| Pelvic floor muscle relaxation |

Various methods can be used to achieve this, including verbal instruction, EMG biofeedback, ultrasound biofeedback and the use of trainers (previously known as dilators) |

IIB,25 |

| Vaginal trainers |

Trainers (previously known as dilators) are plastic or silicon rods with a round end, used to apply pressure at the vaginal entrance and, if possible, inserted into the vagina. Trainers usually come in sets of increasing size to be progressed through. Some practitioners prefer to teach patients to use their own fingers in place of trainers |

IIB,25 |

| Systematic desensitisation |

Systematic desensitisation is a type of behavioural sex therapy where pelvic floor muscle relaxation and insertion of a dilator or finger into the vagina is used to reduce the anxiety and fear associated with penetration |

I26 |

| Cognitive behavioural therapy |

Graded exposure exercises are incorporated with cognitive restructuring to reduce sexual avoidance behaviours |

I26 |

| Pharmacological therapy |

Most medications for vaginismus have limited evidence and are, therefore, not recommended by clinical practice guidelines.23 Botulinum toxin A injections to the puborectalis and pubococcygeus are increasingly being used for treating vaginismus but have limited supporting evidence27 |

NS; botulinum toxin A IV28 |

ANational Health and Medical Research Council level of evidence.

BAs part of a wider, multidisciplinary treatment program.

EMG, electromyography biofeedback; IV, intravenously; NS, treatment not supported by literature. |

Achieving acceptable patient outcomes with people with vaginismus can be time-consuming and take some trial and error. A 2018 systematic review by Maseroli et al suggests around 80% of people with vaginismus responded to multimodal treatment; however, the results varied across the type of multimodal therapy used.26 Most studies use pain-free penetration as a marker of intervention success, which puts the onus of a sexually healthy relationship on the person suffering with vaginismus. Instead, many clinicians and researchers encourage sexual health, pleasure and relationship dynamics as more appropriate measures of success for therapy.7

Conclusion

Vaginismus is a leading cause of painful sex and is characterised by persistent difficulties of the woman to allow vaginal entry of a penis, finger or object, despite the woman’s expressed wish to do so. GPs play an integral role in diagnosing and managing vaginismus. A differential diagnosis of vaginismus can be made with a thorough history-taking, genital examination and single digit vaginal examination (if able). Successful treatment of vaginismus is generally multidisciplinary and involves a combination of patient education, pelvic floor muscle relaxation, use of vaginal trainers and psychological therapy.

Key points

- We currently lack an understanding of the aetiology of vaginismus, but the fear-avoidance model can be helpful to conceptualise the condition.

- Predisposing factors for vaginismus include explicit and implicit sociocultural attitudes around sex.

- Validating a person’s experience with vaginismus is the first step in its management.

- Management should be multidisciplinary, including GPs, sexual counsellors, clinical psychologists, physical therapists, pain specialists and gynaecologists.

- Successful treatment generally involves a combination of patient education, pelvic floor muscle relaxation, use of vaginal trainers and psychological therapy.