The expanding use of mesh prostheses for vaginal prolapse and incontinence surgery from 2000 saw increasing reports of adverse outcomes in women. These reports predominantly described mesh erosion, pain and infection and were followed by intense criticism of surgeons and of the inadequate systems for registering new surgical devices. We have also seen a stringent upgrading of scientific and clinical data requirements for device registration,1 a Senate inquiry resulting in strict guidelines on training and credentialling for use of vaginal mesh and significantly broadened audit mechanisms.2 The Australian Pelvic Floor Prostheses Registry (https://apfpr.org.au) has been established to enable long-term monitoring of outcomes, and the introduction of a unique device identifier (UDI) for all implantable devices is imminent.3

Ideally, we would have had such systems in place before the introduction of new technologies. We might then have been able to promptly recognise developing issues and avoid some of these complications. However, historically, these processes have never been rigorous. Since the establishment of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in 1989, surgical devices that had ‘substantial equivalence’ to predicate devices already on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) had been included without extensive specific clinical data. This was the situation for virtually all medical and surgical devices.

It was the same process by which pelvic floor mesh prostheses were listed on the ARTG. In retrospect, there were, not uncommonly, important differences between these products.

In response to the censure over lax regulatory requirements, the TGA upgraded all vaginal prolapse mesh devices from Class II to the highest risk category, Class III, previously reserved for active implantable devices such as pacemakers. This meant substantial pre- and post-marketing research would now be required.4

In the United States, rigorous pre- and post-marketing research – ‘522 studies’ – was also mandated.5 The final results of research clearly demonstrated equivalent effectiveness and safety of transvaginal prolapse mesh compared to native tissue repair. However, in 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised outcome expectations, declaring that mesh repairs had to show a superior efficacy and equal safety profile.6 In Australia, many companies made the commercial decision that the costs for application and research exceeded the profits to be made in such a small market.7 By March 2022, increasingly restrictive requirements for device use saw only one mid-urethral sling (MUS) manufacturer left in Australia.8 And for some time, we had no available mesh for the proven most effective procedure for significant vault prolapse, the abdominal or laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.9

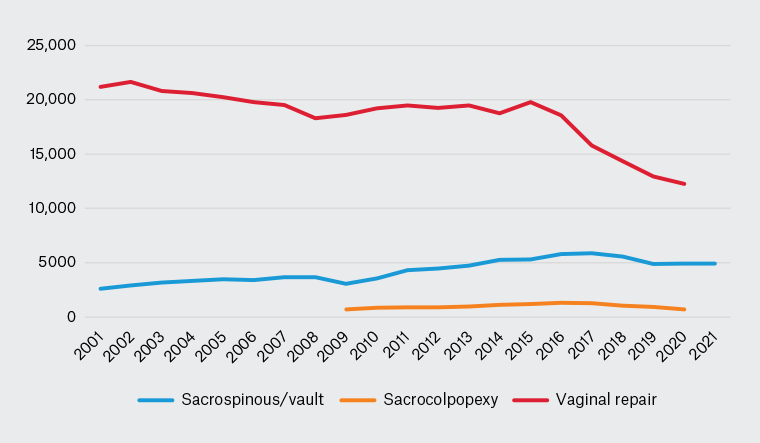

So, where are we now with transvaginal mesh prostheses? What has been the effect on Australian women? Predictably, the initial outcome was for patients to refuse procedures involving mesh, and surgeons were almost equally reluctant. From 2011, there was an immediate fall in the number of mesh-augmented repair procedures,10 and from 2014 to 2015, there was a corresponding reduction in native tissue repair surgeries (Figure 1).11

Figure 1. Mesh and non-mesh prolapse repairs in Australia, 2001–21.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Hospital Morbidity Database (www.meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/394352).

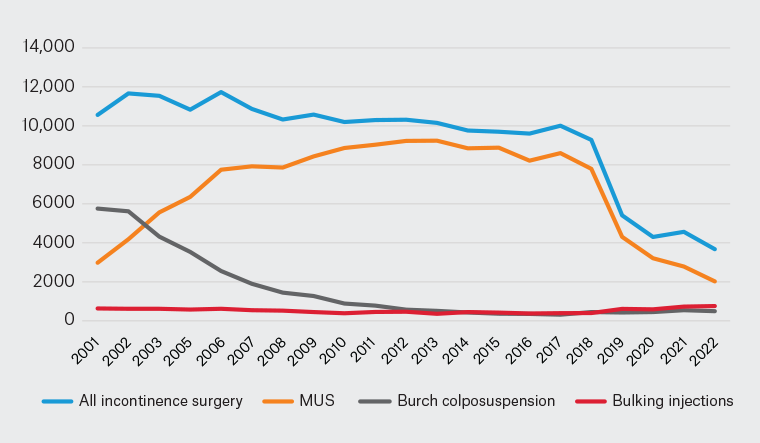

A similar decline has been seen in the use of mesh MUS for stress urinary incontinence. Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW; www.meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/394352) reveal a 64% fall in the use of MUS from the peak usage in 2010–11 (Figure 2). Yet, there has been no corresponding increase in any of the alternative procedures for incontinence. Overall numbers of incontinence procedures in Australia are now less than that at the introduction of the MUS in 1998.12 Nor is this deficit being matched by an uptake in conservative treatment options such as physiotherapy. The conclusion can only be that many women are simply not seeking care for their urinary incontinence and prolapse.

Figure 2. Incontinence surgery in Australia, 2001–22.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Hospital Morbidity Database (www.meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/394352).

MUS, mid-urethral sling.

It is difficult to understand why this response has been so overwhelming. For the MUS, we have more than two decades of sound data confirming this procedure to be as or more effective with less morbidity than the procedures it replaced. Mesh-augmented repairs have also allowed us to treat many older, more frail patients who were not suitable for open abdominal or laparoscopic techniques.12

And this is not the first time concerns have been raised over complications from medical equipment. In recent years, we have seen the recall of several surgical devices. An example is surgical staplers, which required no pre-market data for registration. However, an analysis of device reports from 2011 to 2018 revealed there had been 41,000 reported incidents, more than 9000 serious injuries and 366 patient deaths attributed to surgical staplers.13 FDA data from 2020 showed that surgical staplers were consistently in the top 10 devices causing patient adverse events and death.14

A metal-on-metal-type hip implant was withdrawn in 2010 following evidence of a significantly higher revision rate compared to other hip implants. This was despite ARTG inclusion based on its similarity to other prostheses. However, by 2009, it was clear that complications such as revision, infection and possible leaching of heavy metals were a significant concern.15

In 1992, Australia was the first country in the Asia-Pacific region to approve the gastric band procedure for obesity surgery. Over 80,000 Australians have undergone this surgery. Complications have occurred in approximately 13% of patients, with over 22% requiring reversal or revision.16,17 And yet, in all these cases, the focus was on optimising safer use of the devices without restriction of product availability.18–20

International and Australian data put the rate of revision surgery for mesh procedures at three to five per cent of patients at 10 years postsurgery.21–23 How do we determine which adverse outcomes warrant severe limitations on use? Why was it not possible to find a middle road where patients could still safely access the care they needed when this was achieved for other prostheses with more concerning complication profiles?

Regardless of the disparity in response, we did not manage the introduction of mesh procedures as well as we could have. The lessons are clear. We cannot introduce new devices or techniques without rigorous evaluation and ongoing audit. Our research trials can be run with assistance of industry, but clinicians must ask the questions and set the standards. Outcomes are unquestionably better in specialised high-volume units, so it is incumbent upon us to accept specialised training and credentialling. Similarly, it cannot be acceptable to allow a lesser level of training for procedures simply so patients can access that procedure in their local area. Rather, we need to restructure our patterns of specialist care in rural and regional areas.

In this way, we might encourage women to again feel confident in seeking help for their pelvic floor dysfunction.