Murmurs result from perturbations in blood flow from pressure gradients or velocity changes that cause turbulent blood flow and vibration.1 When evaluating a child with murmurs, several important questions need to be addressed, including the presence or absence of structural abnormalities, haemodynamic disturbances, functional disability and therapeutic options.

Cardiac murmur might be the first clinical sign of a significant congenital heart disease (CHD) in children.2 Other than acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) with valvular dysfunction, cardiac murmur is not a consistent finding in most of the acquired heart diseases in children. The absence of murmurs does not exclude heart problems. Most childhood murmurs are innocent and occur due to normal flow patterns without any structural defects in the heart. Conversely, pathological murmurs are created by abnormal blood flow that could arise from congenital or acquired heart abnormalities.

This review provides a simplified comprehensive update on cardiac murmurs and associated conditions in neonates and children, with focus on CHD.

Prevalence

Globally, CHD affects approximately nine of every 1000 live births, resulting in an estimated 2400 affected babies in Australia each year. In 2016–17, there were nearly 5000 hospitalisations in Australia related to CHD.3 Among babies diagnosed with CHD, approximately one in four have a significant form of the disease (critical CHD), often requiring surgery or other procedures within their first year of life.4 The incidence and prevalence of ARF and RHD are high among First Nations people in some parts of Australia.5

In Australia, CHD was identified as the underlying cause of 152 deaths in 2017, accounting for 0.1% of all deaths. Among these deaths, 70 occurred in infants, constituting 6.9% of all infant deaths in the country.3 Progress in paediatric cardiac care has contributed to an increased number of adults living with CHD.3

The use of detailed anatomical ultrasonography during pregnancy has facilitated the prenatal diagnosis of an increasing number of cases of CHD.6 However, there is still a notable rate of delayed diagnosis, observed in approximately 10% of cases of severe CHD.7 It is worth noting that although approximately 50% of children experience a cardiac murmur at some point in their lives, <1% of these murmurs are attributed to CHD.8 In one particular study, it was found that 2.7% of school children had a murmur, with 18% of them having murmurs with a grade of ≥3 (of 6) in loudness and 9% having structural heart defects.9

The global prevalence of the eight most common CHDs at birth is as follows: ventricular septal defect (VSD), 34%; atrial septal defect (ASD), 13%; patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), 10%; pulmonary stenosis, 8%; tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), 5%; coarctation of aorta (CoA), 5%; transposition of great vessels (TGA), 5%; and aortic stenosis, 4%.10

CHDs commonly seen in adults include ASD (10–15%), PDA, VSD (10%), CoA, TOF, single ventricle, Ebstein anomaly of the tricuspid valve and corrected transposition of great vessels.11

Acquired heart diseases commonly affecting children in Australia from 2017 to 2021 were ARF (3.1 per 100,000), RHD (67 per 100,000 of population), Kawasaki disease, complications in previously treated CHD, myocarditis, endocarditis, cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias. Ninety-two per cent of cases of ARF and 78% of cases of RHD occurred in First Nations people (adults and children). The highest prevalence rate of ARF was in the Northern Territory (984 per 100,000 of population). In Australia, of all people (adults and children) living with a diagnosis of ARF and/or RHD, 3053 (31%) had ARF only, 3237 (33%) had RHD only, and 3632 (37%) had both ARF and RHD.5

History and physical examination

A complete history and physical examination are important for evaluating a cardiac murmur.12 Cardiovascular symptoms and signs could be specific or non-specific.13 Feeding difficulties, dyspnoea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue and coughing are some of the more common presenting complaints.14 Chest pain and syncope are less likely to lead to a CHD diagnosis in children. Congenital anomalies in other organ systems, chromosomal and genetic syndromes, mother and other first-degree relatives with cardiac defects, maternal alcohol and certain medication exposure, abnormal foetal morphological ultrasound and the presence of pathological murmurs increase the probability of structural heart defects.15,16 Red flags in history and physical examination are listed in Box 1.

| Box 1. Red flags when evaluating a cardiac murmur |

Red flags in the history of infants and children

- Feeding difficulties, diaphoresis

- Respiratory distress, tachypnoea, cyanosis, low saturation, frequent respiratory illness, chronic cough

- Fatigue, palpitations, reduced exercise capacity, precordial pain

- Dizziness, presyncope/syncope

- Prematurity (PDA), Kawasaki disease (coronary dilatation and stenosis), previous history of acute rheumatic fever and/or rheumatic heart disease, murmur in First Nations children, infective endocarditis

|

Red flags in physical examinations of infants and children

- Failure to thrive, developmental delay

- Respiratory distress, hypoxia

- Oedema, ascites, hepatomegaly, cyanosis and clubbing

- Arrhythmia, tachycardia, shock, weak femoral pulse

- Abnormal S2, harsh systolic murmur Grade ≥3 (of 6) loudness, louder when standing, long murmur (PSM), diastolic murmur

- Precordial bulge, heave, thrills

- ARF: fever, carditis – tachycardia and murmur (50–79%), arthalgia or aseptic mono‑ or polyarthritis (35–66%), erythema marginatum (<6%), subcutaneous nodules (0–10%) and Sydenham’s chorea (10–30%)16

- Congenital defects in other organ systems

- Syndromic/dysmorphic children

|

Red flags in maternal and/or gestational history

- Gestational diabetes, which is associated with characteristic cardiac defects including asymmetric septal hypertrophy, TOF, truncus arteriosus, TGA, VSD, CoA, HLHS, DORV

- Maternal SLE, which is associated with congenital heart block

- Congenital rubella syndrome, which is associated with PDA and peripheral pulmonary stenosis

- Maternal medications during pregnancy, which could cause cardiac defects:

- SSRIs: VSD, BAV

- Lithium: Ebstein anomaly

- Valproate: CoA, HLHS, ASD, VSD, PS

- Amphetamines: VSD, ASD, TGA

- Retinoic acid: conotruncal abnormalities

- ACEi/ARBs: ASD, VSD, PDA, PS

- Binge drinking, which is teratogenic; cardiac defects in FASD are ASD, VSD, TOF, PDA

|

Red flags in family history

- Sudden cardiac death

- Marfan syndrome (associated with mitral valve prolapse syndrome, mitral regurgitation, aortic regurgitation, aortic aneurysm)

- CHD in first-degree relatives (offspring of mothers with CHDs have a greater than fivefold risk of having a CHD themselves compared with offspring of mothers without CHDs)

|

| ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; ARF, acute rheumatic fever; ASD, atrial septal defect; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CHD, congenital heart disease; CoA, coarctation of aorta; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; FASD, fetal alcohol spectrum disease; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; PSM, pansystolic murmur; S2, second heart sound; maternal SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TGA, transposition of great vessels; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventral septal defect. |

Genetic and metabolic syndromes associated with cardiovascular abnormalities

Some chromosomal, genetic and metabolic syndromes are associated with characteristic congenital heart defects. These syndromes are rare, but identifying the presence of CHD in these conditions is very important.16–18 Some of the classic syndromes and their associated CHDs are listed in Table 1.

| Table 1. Major genetic and metabolic syndromes associated with cardiovascular abnormalities |

| Syndrome |

Associated CHD |

| Alagille syndrome |

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis |

| CHARGE syndrome |

TOF, truncus arteriosus |

| Cornelia de Lange syndrome (5p deletion) |

VSD |

| Down syndrome |

VSD, atrioventricular septal defect (endocardial cushion defect) |

| DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion) |

Frequencies of cardiovascular abnormalities in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome:44 interrupted arch (13%), TOF (20%), VSD (14%), truncus arteriosus (6%), PDA (20%) |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Cardiomyopathy |

| Holt–Oram syndrome |

ASD, VSD |

| Inborn errors of metabolism (eg glycogen storage disease) |

Cardiomyopathy |

| Kartagener syndrome |

Dextrocardia is present in 12% of Kartagener syndrome patients16 |

| LEOPARD syndrome (12q24.13 mutation) |

Pulmonary stenosis, HOCM |

| Marfan syndrome (15q21.1 mutation) |

Aortic aneurysm, aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation, mitral valve prolapse |

| Noonan syndrome (12q24.13 mutation) |

Pulmonary stenosis, left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 (AD, 17q11.2 mutation) |

Pulmonary stenosis, CoA |

| Pierre Robin sequence |

VSD, PDA |

| Congenital rubella syndrome |

PDA, pulmonary artery stenosis |

| Turner syndrome (XO) |

CoA, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic stenosis |

| VACTERL association |

VSD |

| Williams syndrome |

Aortic stenosis, pulmonary stenosis |

| ASD, atrial septal defect; CHARGE, coloboma, heart disease, atresia of the choanae, retarded growth and mental development, genital anomalies, and ear malformations and hearing loss; CHD, congenital heart disease; CoA, coarctation of aorta; HOCM, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VACTERL, vertebrae, anus, heart, trachea, esophagus, kidney and limbs (parts of the body affected); VSD ventral septal defect. |

Innocent murmurs and pathological murmurs

Innocent murmurs are commonly referred to as flow murmurs, physiological murmurs or functional murmurs. In contrast, pathological murmurs are more often associated with congenital or acquired structural heart disease and often require medical or procedural interventions. Characteristics of pathological or significant cardiac murmurs are that they are harsh and loud (Grade ≥3 [out of 6] intensity), pansystolic, diastolic, louder or similar in the standing position, a continuous murmur that cannot be suppressed, a click or opening snap is present. The presence of central cyanosis, abnormal heart sounds, abnormal peripheral pulses and an abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG) also suggest a pathological murmur. Where ARF or infective endocarditis is considered as a diagnostic possibility, the appearance of any new murmur should be considered as pathological. Differences between innocent and pathological murmur are summarised in Table 2.

| Table 2. Differences between innocent and pathological murmurs |

| |

Innocent murmur (all the following features) |

Pathological murmur (any of the following features) |

| Intensity |

Generally soft and low-pitched sounds, less than Grade 3

Louder with exercise, anaemia and fever |

Loud or harsh-sounding, Grade 3 or louder |

| Duration |

Short |

Might be long-lasting |

| Location |

Heard best at the left lower sternal border or at the apex of the heart |

Depending on the underlying structural abnormalities, heard in multiple areas of the chest |

| Timing |

Systolic |

Murmurs due to structural heart disease might occur during systole, diastole or throughout the cardiac cycle |

| Position |

Murmur most audible in the supine position and disappears upon assuming an upright position |

Often the same intensity in both supine and upright positions |

| Radiation |

No radiation to other areas of the chest |

Might radiate to the neck or back |

| Associated symptoms |

Absence of associated symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest pain or fatigue |

Associated symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest pain or fatigue |

Associated

signs |

Absence of other abnormal cardiac signs including clubbing, cyanosis, clicks or added sounds, tachycardia or hypertension |

Presence of clubbing, cyanosis, ejection clicks or added sounds, tachycardia or hypertension |

Examples of functional or innocent murmurs include those in the:

- upper left sternal border or pulmonary area: pulmonary flow murmurs in neonates and children, venous hum and peripheral pulmonary stenosis (also in lateral chest)

- lower left sternal border or tricuspid area: Still’s murmur

- apex or mitral area: Still’s murmur

- sternoclavicular area: venous hum (also continuous)

- lower right neck: ejection systolic murmur of carotid bruit.19

Differential diagnosis according to the site of murmurs

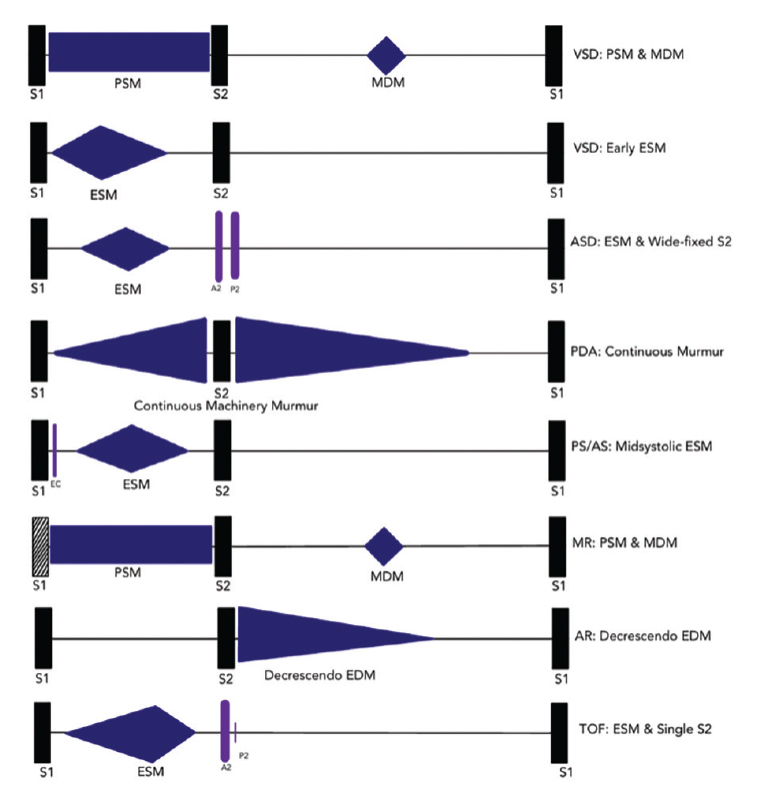

The description of murmurs should include timing (systole or diastole), length, pitch, intensity, variation with respiration or posture and radiation. It is critical to consider the differential diagnosis or underlying cause based on the location of the maximum intensity of the murmur. Differential diagnoses of common heart murmurs and auscultatory findings of common congenital and acquired heart diseases in children are summarised in Tables 3–6 and Figure 1.

| Table 3. Differential diagnosis of systolic and continuous murmurs based on the location of maximum intensity of the murmur |

| Pulmonary area |

Tricuspid area |

Mitral area |

Aortic area |

Acyanotic:

- Perimembranous VSD

- PDA with pulmonary hypertension

- Pulmonary valve stenosis

- Pulmonary artery stenosis

- Peripheral PS

- Pulmonary flow murmur in ASD

- Aortic stenosis

- CoA

|

Acyanotic:

- VSD

- Tricuspid regurgitation

- HOCM

|

Acyanotic:

- Mitral regurgitation

- Mitral stenosis

- Mitral valve prolapse syndrome

- Aortic stenosis

- HOCM

- AR or mitral regurgitation in rheumatic fever

|

Acyanotic:

- Valvular aortic stenosis

- Subaortic stenosis

- Supravalvular aortic stenosis

|

Cyanotic:

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Anomalous venous return

- Truncus arteriosus

- Single ventricle

|

Cyanotic:

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- TGA with VSD

- Ebstein anomaly

|

|

|

Continuous:

- PDA

- Intercostal collateral in severe long-standing CoA

- VSD or PS with AR or PR

- Pulmonary arteriovenous fistula

- Aortopulmonary window

|

Continuous:

- Severe CoA

- VSD or PS with AR or PR

- TAPVR draining in right atrium

|

|

Continuous:

- Coronary arteriovenous fistula

- Truncus arteriosus

|

| AR, aortic regurgitation; ASD, atrial septal defect; CoA, coarctation of aorta; HOCM, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PR, pulmonary regurgitation; PS, pulmonary stenosis; TAPVR, total anonymous pulmonary venous return; TGA, transposition of great arteries; VSD, ventricular septal defect. |

| Table 4. Differential diagnosis of diastolic murmurs based on the location of maximum intensity of the murmur |

| Pulmonary area |

Tricuspid area |

Mitral area |

Aortic area |

Early DM:

- PR in post-surgical TOF and pulmonary valvuloplasty

- Pulmonary hypertension

|

Mid DM:

- ASD, endocardial cushion defect, tricuspid stenosis, anomalous venous return

Late DM:

|

Early DM:

- AR in BAV, subaortic aortic stenosis, post-surgical RHD

Mid DM:

- Mitral stenosis, VSD, PDA

Late DM:

|

Early DM:

|

| AR, aortic regurgitation; ASD, atrial septal defect; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; DM, diastolic murmurs; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PR, pulmonary regurgitation; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect. |

| Table 5. Auscultatory findings in common congenital heart diseases in children |

| Condition |

Heart sounds and pulse |

Systolic murmur |

Diastolic murmur |

| Ventricular septal defect |

- If PHT develops, P2 is loud

|

- In LLSB loud, harsh, blowing Grade 3–5 (of 6) PSM (or ESM)

|

- Grade 1–2 (of 4) MDM in apex if LA volume overload develops

|

| Atrial septal defect |

|

- Grade 2–3 (of 6) ESM (pulmonary flow murmur) in ULSB radiating to back

|

- MDM in LLSB with large left-to-right shunt

|

| Patent ductus arteriosus |

- S1 and S2 normal

- If PHT develops, P2 is loud

- Bounding pulses

|

- Grade 3–4 (of 6) continuous murmur in ULSB

|

- Grade 1–2 (of 4) MDM in apex if LA volume overload develops

|

| Coarctation of aorta |

- S1 and S2 normal usually

- Click with BAV

- Upper limb BP higher, weak femoral pulse, radiofemoral delay

|

- ESM or PSM is present in ULSB in 50% of the CoA cases, apex and interscapular region

- Continuous murmur of enlarged collaterals in anterior and posterior chest

|

|

| Aortic stenosis |

- Narrow S2, ejection clicks

- Normal or reduced pulse

|

- Harsh Grade 2–4 (of 6) ESM in URSB radiating to neck

|

|

| Pulmonary stenosis |

- Soft and wide S2, ejection clicks

- Normal pulse

|

- Grade 2–5 (of 6) ESM in ULSB radiates to back

|

|

| Tetralogy of Fallot |

- Single S2

- Normal pulse

- Cyanosis, lower than 94% saturation with pulse oximetry

- Hypercyanotic spells

|

- Harsh and loud Grade 3–5 (of 6) ESM in ULSB or MLSB (from RVOT) which become softer during hypercyanotic spells

- VSD murmur in LLSB in acyanotic TOF and post-surgery residual VSD

- Palliative shunt murmur in classic BTS or MBTS (RPA/LPA + subclavian) and Waterston’s shunt (Ao+RPA/MPA)

|

|

| Single ventricle |

- Single S2

- Cyanosis since birth

- CCF

- Duct dependent

|

- Grade 2–4 (of 6) ESM in ULSB

- Continuous PDA murmurs on either side of chest

|

|

| Transposition of great arteries |

- Single loud S2

- Cyanosis since birth

- CCF

|

|

|

| Ao, aorta; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; BP, blood pressure; BTS, Blalock–Taussig shunt; CCF, congestive cardiac failure; ESM, ejection systolic murmur; LA, left atrium; LLSB, lower left sternal border; LPA, left pulmonary artery; MBTS, modified Blalock–Taussig shunt; MDM, mid-diastolic murmur; MLSB, mid left sternal border; MPA, main pulmonary artery; P2, pulmonary second sound; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PHT, pulmonary hypertension; PSM, pansystolic murmur; RPA, right pulmonary artery; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; S1, first heart sound; S2, second heart sound; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; ULSB, upper left sternal border; URSB, upper right sternal border; VSD, ventricular septal defect. |

| Table 6. Auscultatory findings in common acquired heart diseases in children |

| Condition |

Heart sounds and pulse |

Systolic murmur |

Diastolic murmur |

| Acute rheumatic fever |

- Normal heart sounds

- Pericardial friction rub

|

- Grade 2 (of 6) MR or AR systolic murmurs in apex

|

- Diastolic murmur in apex (MDM or early systolic)

|

| Mitral stenosis |

- Loud S1, loud P2 (if PHT), opening snap in apex or LLSB

|

- Systolic murmur if tricuspid regurgitation is present

|

- Diastolic murmur in apex (MDM or early systolic)

|

| Mitral regurgitation |

- Soft, absent or normal S1, wide split S2, S3 at apex in severe MR

|

- Grade 3 (of 6) PSM in apex in moderate to severe MR

|

|

| Aortic regurgitation |

- S1 is soft or normal

- Single S2, wide pulse pressure

|

|

- High-pitched diastolic blowing decrescendo murmur in LPSB

- MDM in apex

|

| AR, aortic regurgitation; ESM, ejection systolic murmur; LLSB, lower left sternal border; LPSB, left parasternal border; MDM, mid-diastolic murmur; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; PHT, pulmonary hypertension; PSM, pansystolic murmur; S1, first heart sound; S2, second heart sound; S3, third heart sound; URSB, upper right sternal border. |

Figure 1. Auscultatory findings in common childhood cardiac conditions.

A2, aortic second sound; AR, aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; ASD, atrial septal defect; EC, ejection click; ESM, ejection systolic murmur; MDM, mid-diastolic murmur; MR, mitral regurgitation; P2, pulmonary second sound; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PSM, pansystolic murmur; S1, first heart sound; S2, second heart sound; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Atrial septal defect

ASD is usually asymptomatic and could remain undiagnosed in childhood. Seventy per cent of ASDs are of the ostium secundum type. The sinus venosus type (10% of all ASD cases) is almost always associated with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR). A wide and fixed-split second heart sound (it does not narrow or become single with a held expiration) is pathognomonic. Of the ASDs diagnosed in childhood, 20–30% enlarge over time. Surgical closure or closure in the catheter laboratory with a device is usually recommended, even for asymptomatic adults because of the higher incidence of strokes due to paradoxical embolus (and atrial fibrillation).20–22

Ventricular septal defect

Perimembranous VSD is the most common type (70%) and muscular VSD is the second most common (25%). Many small and medium-sized VSDs are asymptomatic and close spontaneously, particularly muscular VSDs. Untreated larger defects lead to left-sided volume overload (cardiomegaly on chest X-ray and left atrial enlargement with left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG), congestive cardiac failure and pulmonary hypertension. Large VSDs will most likely need surgical closure. Small and medium-sized defects (eg persisting perimembranous VSDs) are increasingly closed with devices in the catheter laboratory.

Patent ductus arteriosus

Continuous machinery murmur due to left-to-right shunt in both systole and diastole (due to higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the aorta than in the pulmonary artery) in the upper left sternal border with a bounding pulse (due to a wider pulse pressure) are indicative of PDA. Calcification of PDA could be noted on chest X-ray. Almost all PDAs are closed with a device in the catheter laboratory without surgery.

Tetralogy of Fallot

Four components of TOF are right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction, a large VSD, aortic override and right ventricular hypertrophy. Chest radiography could detect a boot-shaped heart, oligaemic lung field and right-sided arch. Patients are asymptomatic and acyanotic if RVOT obstruction is mild. In severe RVOT obstruction, patients are cyanosed and present with more frequent hypercyanotic spells, during which classical murmurs become softer or disappear. Surgical relief of RVOT obstruction and closure of VSD have very good outcomes. Temporary palliative shunt surgery is sometimes essential if pulmonary arteries are underdeveloped. All surgically closed TOF patients will need lifelong follow-up because of the higher risk of sudden death due to ventricular tachycardia.

Investigations

Although echocardiography is highly valued for its cost-effectiveness and is often considered the preferred diagnostic method for pathological murmurs, it is not usually necessary in most cases of innocent murmurs.23 Innocent murmurs, commonly found in older infants and children, do not indicate structural heart defects, and therefore do not require echocardiography in the majority of cases.

In neonates and young infants, it is advisable to have lower thresholds for investigations and referral to paediatric cardiology due to the higher prevalence of CHD in this population. Despite careful routine medical examinations at birth, approximately 50% of cases of CHD remain unrecognised.24 The use of digital intelligent phonocardiograms is a cost-effective method for detecting significant cardiac murmurs in newborns, potentially improving CHD detection rates by an additional 58%.24,25 In addition, in asymptomatic neonates with cardiac murmurs, performing pulse oximetry 24 hours after birth could increase the detection rate of CHD from 46% to 77%,26 and conducting echocardiography in these neonates could detect an additional 37% of cases.27

In asymptomatic neonates and children with innocent or pathological murmurs, chest radiography, ECG and pulse oximetry have limited value in initial diagnosis.28–31 Nonetheless, chest radiography could provide information about situs (eg dextrocardia), aortic arch side, atypical cardiac shadow (eg ‘boot shape’ in TOF, ‘egg on a string’ in transposition of great arteries, ‘snowman’ in total anomalous pulmonary venous return, ‘reverse figure of 3’ in CoA and ‘box shape’ in Ebstein anomaly)32–34 and lung field characteristics (eg oligaemic appearance in TOF or plethoric appearance in VSD and PDA), and ECG could be useful in identifying arrhythmias, conduction disorders, atrial enlargement and ventricular hypertrophy in children with CHD and, more importantly, in acquired heart diseases.35,36

Indications for referral to local paediatric cardiology services are as follows:

- age under three months (any murmur)12

- if ARF or RHD is suspected (any age)37

- known CHD relocating to the area

- if an abnormality is detected in a detailed foetal morphological scan

- infants and children aged over three months with a pathological murmur (when an innocent murmur cannot be diagnosed)13,38,39

- when there is a family history of CHD in first-degree relatives, Marfan syndrome, cardiomyopathy or unexplained sudden death

- if the child is known to have chromosomal or genetic conditions that are associated with heart diseases

- failure to thrive, poor growth, difficulty in feeding

- abnormal symptoms such as breathlessness, frequent chest infections, unable to keep up with friends

- cardiac symptoms such as palpitations, syncope or chest pain

- other abnormal cardiac signs (clubbing, cyanosis, clicks or added sounds, rapid heart rate or high blood pressure).39–41

Conclusion

Significant skill and knowledge are required for the identification of critical murmurs and associated cardiovascular problems.42 Children at risk of heart diseases should be identified with thorough history taking, careful physical examination and rational investigations, and appropriate referral should be made without delay to a paediatric cardiology service. Ongoing education of medical practitioners would improve their skills and confidence in diagnosing heart diseases with cardiac murmurs, which will reduce anxiety in parents43 and improve patients’ outcomes (Box 2).