Individuals experiencing persistent symptoms of COVID-19 from four to 12 weeks after infection are classified as having ongoing symptoms of COVID.1 The 5–50% of people experiencing often debilitating symptoms after 12 weeks are considered to have post-COVID-19 syndrome.1–3 As is the case with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, symptoms of post-COVID-19 syndrome are highly variable, can fluctuate over time and affect physical ability, cognition, mental health, activities of daily living (ADL), participation in society and health-related quality of life;2,4–9 nearly one-third of people have not returned to work by three months after infection and 39% experience work impairments as a direct result of their illness.10

The trajectory of post COVID-19 syndrome is challenging for general practitioners (GPs), who might be providing care in the absence of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and in an area where new evidence is rapidly emerging.11 Internationally, it has been reported that people who were vaccinated are less likely to experience ongoing symptoms of COVID-19;12–14 however, little is known regarding unvaccinated people in Australia. This is especially important because over 28,000 Australians were diagnosed with COVID-19 prior to a vaccine being available and approximately 5% of Australians aged over 16 years have not been vaccinated.15,16 Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate symptoms at seven and 13 months in a cohort of non-hospitalised COVID-19 patients prior to vaccine availability.

Methods

Participants and setting

A prospective observational longitudinal cohort study was conducted at The Royal Melbourne Hospital, from February to September 2021. The study was nested within a larger observational pre-vaccination umbrella study investigating the serology of patients with COVID-19. Recruitment for the umbrella study involved contacting patients who had recent positive COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) form samples collected through The Royal Melbourne Hospital or their household contacts. Participants were screened for eligibility and included if they were aged ≥18 years, had a diagnosis of COVID-19 by PCR throat swab at The Royal Melbourne Hospital and were managed in the community at the time of infection. Of note, patients were enrolled prior to the COVID-19 vaccine being available. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, evidenced dementia, were non-ambulant or were living in an aged care facility receiving end of life care. Recruitment was completed during a rapid surge of local cases prior to COVID-19 vaccine availability (98% of which were D.2 linage, also known as B.1.1.25).17

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethics approval was obtained from The Royal Melbourne Hospital (HREC/65534/MH-2020).

Baseline demographic data collected as part of the telephone-based questionnaire included age, gender, past medical history, smoking status and physical activity levels in the month prior to COVID-19 diagnosis. GP, pharmacy and specialist doctor usage in the three and six months prior to COVID-19 diagnosis was recorded as a marker of general health and to describe the health characteristics of the cohort. Participants were also asked to grade their breathlessness at rest, cough and fatigue levels one month prior to being diagnosed with COVID-19 using a scale from 0 to 10, where a score of 0 indicated no symptoms and a score of 10 denoted the worst possible severity. Because participants required a diagnosis of COVID-19 to be eligible for this study, we were not able to collect pre-COVID baseline data.

Outcome measurement

Data were collected at seven and 13 months after COVID-19 diagnosis. Six questionnaires (Appendix 1) were delivered via telephone at two time points (seven and 13 months) to assess function, cognition and wellbeing, namely the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), the functional impairment checklist, EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L), the telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA), the seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression scale, the Primary Care Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) test and taste and smell, which were rated on a scale from 0 (no smell/taste) to 10 (normal).6,7,18–25 Cognition was assessed first. Data were collected at seven and 13 months after COVID-19 diagnosis.

One physical assessment was undertaken in person between 12 and 18 months after COVID-19 infection to assess hand grip strength, forced vital capacity and the six-minute walk test, as well as blood pressure and heart rate (to screen for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome).26–28 Details are described in Appendix 1. This time point was dictated by COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Where symptoms were identified or scores were outside normal values, referrals were offered to GPs, psychology, exercise physiology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, primary care or dietetics, as appropriate.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was based on the number of participants recruited to the umbrella serology study (n=111). Data were extracted from forms and entered into a REDCap application database before analysis using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Windows Version 26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Baseline descriptive data are presented as frequencies and percentages (for categorical data) and as the median and interquartile range (IQR) because most variables were not normally distributed. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to calculate the significance of changes in symptoms from baseline to seven months and to measure changes in fatigue at seven and 13 months. Participants were dichotomised based on their FSS scores being ≥36.29 Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare continuous outcome measure total scores in patients who were fatigued and those who were not. Chi-squared tests were also used to compare categorical symptoms of patients with and without severe fatigue or anxiety/depression.

Results

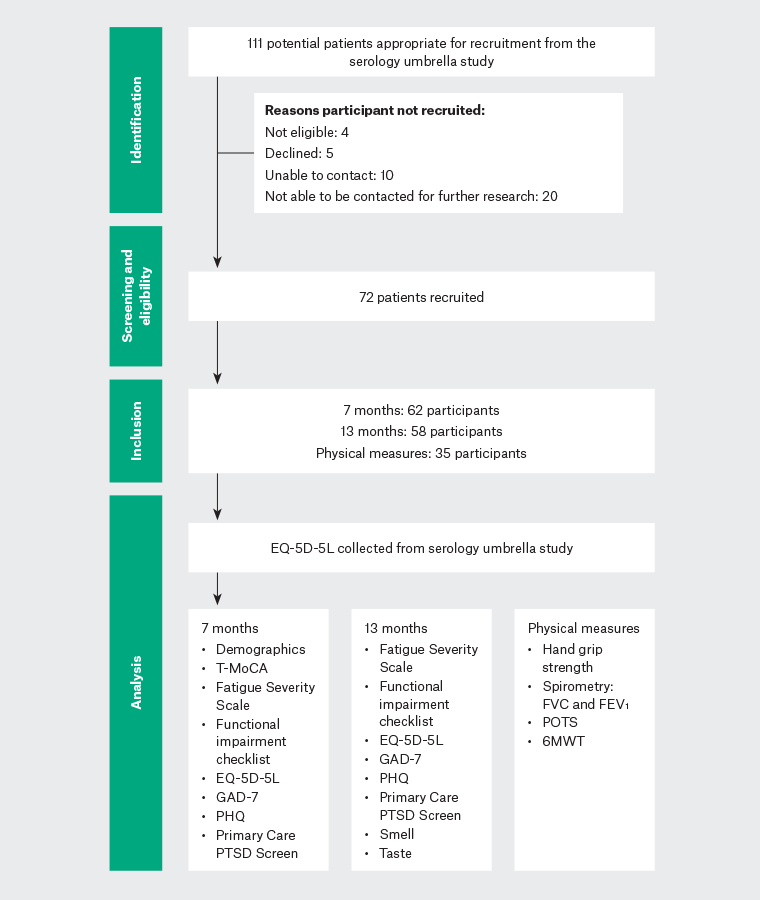

Overall, 111 patients from the umbrella project were approached to participate in this study; 62 participants consented and were recruited (median age 35 years [IQR 27–44 years]; 37 (60%) female; Figure 1). The median time from COVID-19 swab to data collection was 7.5 months (IQR 7.2–7.9 months) at the first time point and 13.8 months (IQR 12.9–14.1 months) for the second time point. Thirty-six (58%) participants were healthcare workers. The in-person measures were scheduled for 12 months after infection; however, due to subsequent lockdowns, this assessment was undertaken at a median of 15.7 months (IQR 14.9–17.2 months) after infection.

Figure 1. Diagram showing the flow of patients through the study.

6MWT, 6-min walk test; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimension 5 Level; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GAD-7, seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale; PHQ‑9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; PTSD, post‑traumatic stress disorder; T-MoCA, telephone version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Demographic data and participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. In the three months prior to their COVID-19 infection, most people (n=47; 76%) had less than two GP visits and four (6%) people had seen a specialist in the preceding six months. At seven months, the median FSS score was 36 (IQR 22–48), with approximately half the participants (n=30; 48%) classified as having severe fatigue. At 13 months, 45% (n=26) of participants reported severe fatigue. The change in participants’ fatigue levels was not significant between the two time points (t=20.21, z=–1.68, corrected for ties; n–ties=48, P=0.09, two tailed). At 13 months, 27 participants had lower FSS scores (less fatigued; sum of ranks=751.50), whereas 20 had higher FSS scores (more fatigued; sum of ranks=424.50) relative to seven months. Six participants reported no change between seven and 13 months. The median FSS scores improved in the follow-up period for those severely fatigued at seven months (13 months: 44 [IQR 39–51] vs 48 [IQR 42–55]) but remained severe by classification.

| Table 1. Patient demographics |

| |

All participants |

| 7 months (n=62) |

13 months (n=58) |

| Fatigue |

| Fatigue Severity Scale (possible scores 9–63) |

36 [22–48] |

32 [16–44] |

| Function |

Functional impairment checklist

(possible scores 0–24) |

3 [1–8] |

2 [0–7] |

| EQ-5D-5L (possible scores 5–25) |

7 [5–9] |

7 [5–8] |

| EQ VAS (possible scores 0–100) |

75 [60-85] |

80 [67–90] |

| Cognition |

| MoCA scores (possible scores 0–22) |

20 [19–21]A |

|

| Wellbeing |

| GAD-7 (possible scores 0–24) |

4 [1–7] |

4 [0–8] |

| PHQ-9 (possible scores 0–27) |

4 [2–9] |

5 [2–8] |

| Unmet needs |

| Psychology referral |

14 (23) |

7 (12) |

| Exercise physiology/physiotherapy referral |

15 (24) |

7 (12) |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or count (percentage).

AData were only collected at seven months due to the floor effect.

EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels; EQ VAS, EuroQol visual analogue scale; GAD-7, seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale. |

Participants were generally able to complete basic ADL tasks (Table 1). The constituent items most endorsed at both the seven- and 13-month time points were generalised weakness (n=27 [44%] and n=22 [38%], respectively), muscle weakness (n=20 [32%] and n=17 [29%], respectively), limitation with occupational activities (n=27 [44%] and n=21 [36%], respectively), limitations with social or leisure activities (n=24 [39%] and n=18 [31%], respectively) and limitations with instrumental activities of daily living, such as housework (n=35 [35%] and n=18 [31%], respectively).

General health status median scores on the EQ visual analogue scale were 75 (IQR 60–85) and 80 (IQR 67–90) at seven and 13 months, respectively (Table 1). From the EQ-5D-5L subscores, 19% (n=12) and 24% (n=14) of participants indicated problems walking, 37% (n=23) and 36% (n=21) reported problems with usual activities and 34% (n=21) and 28% (n=16) endorsed pain or discomfort at the seven- and 13-month time points, respectively.

As indicated in Table 2, participants who were severely fatigued had significantly worse function than those who were not. EQ-5D-5L scores were also worse in individuals with severe fatigue at both time points. Participants with severe fatigue reported significantly greater generalised weakness and muscle weakness, as well as more pain, than participants without severe fatigue (Table 2). Significantly more functional limitations and worse self-reported general health scores were noted in fatigued participants at each time point.

| Table 2. Fatigue, function, cognition, wellbeing and unmet need scores at 7 and 13 months, stratified by fatigued |

| |

7 months |

13 months |

| |

All participants (n=62) |

Severe fatigue (n=30) |

No severe fatigue (n=31) |

P-value |

All participants (n=58) |

Severe fatigue (n=26) |

No severe fatigue (n=32) |

P-value |

| Fatigue |

| Fatigue Severity Scale (possible scores 9–63) |

36 [22–48] |

48 [42–55] |

22 [17–28] |

<0.001 |

32 [16–44] |

45 [42–52] |

17 [13–26] |

<0.001 |

| Function |

| Functional impairment checklist (possible scores 0–24) |

3 [1–8] |

7 [4–10] |

2 [1–3] |

<0.001 |

2 [0–7] |

8 [2–13] |

0 [0–1] |

<0.001 |

| Breathlessness at rest |

11 (17) |

8 (27) |

3 (10) |

<0.08 |

7 (12) |

6 (23) |

1 (3) |

0.02 |

| Breathlessness on exertion |

51 (82) |

27 (90) |

24 (74) |

0.185 |

30 (48) |

18 (69) |

10 (31) |

0.004 |

| Generalised weakness |

27 (44) |

19 (63) |

8 (26) |

0.003 |

22 (38) |

19 (73) |

3 (9) |

<0.001 |

| Muscle weakness or wasting |

20 (32) |

15 (50) |

5 (16) |

0.011 |

17 (29) |

15 (58) |

2 (6) |

<0.001 |

| Limitations with occupational activities |

27 (44) |

23 (77) |

13 (13) |

<0.001 |

21 (36) |

18 (69) |

3 (9) |

<0.001 |

| Limitations with social/leisure activities |

24 (39) |

21 (70) |

3 (10) |

<0.001 |

18 (31) |

16 (62) |

2 (6) |

<0.001 |

| Limitations with basic ADLs |

8 (13) |

6 (20) |

2 (7) |

0.117 |

7 (12) |

7 (27) |

0 |

0.002 |

| Limitations with instrumental ADLs |

22 (36) |

19 (63) |

3 (10) |

<0.001 |

18 (31) |

16 (62) |

2 (6) |

<0.001 |

| EQ-5D-5L |

7 [5–7] |

9 [7–10] |

5 [5–6] |

<0.001 |

7 [5–8] |

9 [7–11] |

6 [5–6] |

<0.001 |

| Problems with walking |

22 (36) |

11 (37) |

0 |

<0.001 |

14 (24) |

13 (50) |

1 (3) |

<0.001 |

| Problems with self-care |

4 (6) |

4 (13) |

0 |

0.035 |

4 (7) |

4 (15) |

3 (9) |

0.021 |

| Problems with usual activities |

23 (37) |

20 (67) |

3 (10) |

<0.001 |

21 (36) |

19 (73) |

2 (6) |

<0.001 |

| Pain/discomfort |

21 (34) |

17 (57) |

3 (10) |

<0.001 |

16 (28) |

13 (50) |

3 (9) |

<0.001 |

| Anxiety/depression |

33 (53) |

25 (83) |

7 (23) |

<0.001 |

36 (62) |

24 (92) |

12 (21) |

<0.001 |

| EQ VAS (possible scores 0–100) |

75 [60–85] |

70 [50–75] |

80 [70–90] |

<0.001 |

80 [67–90] |

69 [50–75] |

90 [80–95] |

<0.001 |

| Wellbeing |

| GAD-7 (possible scores 0–21) |

4 [1–7] |

6 [4–9] |

3 [0–6] |

0.003 |

4 [0–8] |

7 [4–11] |

2 [0–5] |

<0.001 |

| PHQ-9 (possible scores 0–27) |

4 [2–9] |

9 [4–12] |

2 [1–5] |

<0.001 |

5 [2–8] |

8 [5–12] |

2 [0–5] |

<0.001 |

| Primary Care PTSD Screen |

1 [0–2] |

2 [1–3] |

0 [0–2] |

0.002 |

1 [0–3] |

3 [1–4] |

0 [0–2] |

<0.001 |

| Unmet needs |

| Psychology referral |

14 (23) |

10 (33) |

4 (13) |

0.06 |

7 (12) |

4 (15) |

3 (5) |

0.409 |

| Exercise physiology/physiotherapy referral |

15 (24) |

13 (43) |

2 (7) |

<0.001 |

7 (12) |

6 (23) |

1 (3) |

0.014 |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or count (percentage).

ADLs, activities of daily living; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimension 5 Level; EQ VAS, EuroQol visual analogue scale; GAD-7, seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale; Primary Care PTSD Screen, Primary Care Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Screen. |

Fifteen (24%) participants were found to have mild cognitive impairment (T-MoCA scores <19) at seven months. Median T-MoCA scores were not significantly worse in patients with severe fatigue compared with the overall cohort (20 [IQR 18–21] vs 20 [IQR 19–21], respectively).

As per the GAD-7 at seven and 13 months, respectively, 32 (52%) and 31 (53%) participants had ‘normal’ scores, 21 (34%) and 16 (28%) had ‘mild’ anxiety symptoms, seven (11%) and nine (16%) had ‘moderate’ anxiety and two (3%) and two (3%) severe anxiety. The most endorsed items at the seven- and 13-month time points were feeling nervous (n=46 [74%] and n=38 [66%], respectively), worrying too much (n=40 [64%] and n=31 [53%], respectively), having trouble relaxing (n=35 [56%] and n=33 [57%], respectively) and being easily annoyed (n=34 [55%] and n=34 [59%], respectively). The report of feeling afraid increased between the measurement points (n=22 [35%] vs n=26 [45%] at seven and 13 months, respectively).

At seven and 13 months, 19% (n=12) and 14% (n=8) of the cohort, respectively, recorded PHQ-9 scores above the cut-off for depression. The most endorsed items at the seven- and 13-month time points were trouble falling asleep (n=42 [69%] and n=36 [62%], respectively), trouble concentrating (n=28 [45%] and n=29 [50%], respectively) poor appetite or overeating (n=25 [40%] and n=24 [41%], respectively) and little interest or pleasure (n=23 [37%] and n=25 [43%], respectively). At 13 months, there was greater endorsement on five of the nine PHQ-9 items than seen at seven months.

As indicated in Table 2, GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores at both the seven- and 13-month time points were individually significantly higher in participants who were classified as fatigued, indicating an increased presence of anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively. All participants who reported depression (PHQ-9 >10) at seven months (n=12) and 13 months (n=8) were also classified as being fatigued. Scores above the cut-off for probable PTSD were recorded in 21% (n=13) and 31% (n=18) of participants at the seven- and 13-month time points, respectively, but median scores did not change in the overall group (1 [IQR 0–2] vs 1 [IQR 0–3]; P=0.356) over the follow-up period.

Objective measures were available for 35 participants at 18 months (Table 3) and were largely within normal limits.

| Table 3. Objective measures collected on 35 participants |

| Self-reported taste (range 0–10; 0, no taste; 10, normal) |

10 [8.0–10.0] |

| Self-reported smell (range 0–10; 0, no smell; 10, normal) |

9.5 [8.0–10.0] |

| Participants with lower-than-normal grip strength for their gender/age |

9 (26) |

| Participants with FVC or FEV1 below the lower limit of normal for their height/gender/age |

3 (9) |

| Presence of POTS |

2 (6) |

| 6MWT distance (m) |

543.5 [495.8–621.8] |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or count (percentage).

6MWT, 6-min walk test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. |

Discussion

In this study of non-hospitalised, young, previously healthy Australians infected with COVID-19, there were obvious fatigue, quality of life, anxiety and depression gaps up to one year after illness. Unlike reports from other outpatient studies, the predominant post-COVID-19 symptoms in the present cohort were not dyspnoea at rest or persistent cough, but quality of life limitations.30 Our findings highlight that fatigue, mental health, activity limitations and quality of life impairments might persist at 13 months after a COVID-19 infection in unvaccinated Australians. Physicians might routinely screen for bothersome fatigue and generalised and specific muscle weakness and enquire about limitations with occupational, social, leisure and usual activities, as well as wellbeing, in people after COVID-19 infection. A digital solution with in-built touchpoints to access health advice or escalate concerns to family physicians might support needs-based primary care.31

Fatigue is more than threefold higher after COVID-19 compared with healthy controls and the main symptom that prompts patients to seek help and rehabilitation.32,33 Persisting fatigue is likely to be multifactorial and there might be a reciprocal relationship between fatigue, mood and function (ie a summation of underlying comorbid disease, stress, anger, anxiety, depression, muscle weakness, inflammation and changes in neurotransmitter levels).34 Similar to findings of Menges et al, half of all participants in the present study reported severe fatigue one year after illness.35 Furthermore, the level of fatigue was unchanged between the measurement time points, demonstrating that even in non-hospitalised cases of COVID-19, functional abilities might be compromised long term.

Anxiety, depression and reduced quality of life were observed throughout the study duration. EQ-5D-5L findings of moderate or extreme anxiety or depression in 29% of the cohort are similar to data in hospitalised patients.36 However, anxiety and depression deteriorated significantly between the initial and one-year time points, whereas overall health score stayed the same. This differed from another report where worse general health was associated with greater depression and anxiety.37 Despite up to one-third of all participants demonstrating probable COVID-related PTSD at 13 months, the uptake of referrals for psychological help was less than expected. Given the correlation between PTSD, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation in people with post-COVID-19 syndrome, appropriate screening and referrals are essential.38

A strength of this study was that validated questionnaires and objective measures were used to measure the symptoms of COVID-19. Questionnaires took 20–30 minutes to complete, which might have been challenging in a sample reporting fatigue. The hospital aimed to harmonise all COVID-19 research; accordingly, this study was nested in an existing microbiology umbrella study and, consequently, participants who met both inclusion criterion dictated the small sample size. There might also have been increased burden from multiple study tasks; therefore, we did not exclude other causes for symptoms (eg low iron levels in young women). There was no available control group of patients without COVID-19 with which to compare the study findings. We also did not determine direct and indirect reasons for anxiety or depression (ie limitations, uncertainties, poor sleep and life disruption), nor did we determine whether symptoms were correlated.39 We excluded people who were non-ambulant. Future directions for research in this area should consider the development of clinician-friendly screening tools for ongoing symptoms of COVID-19 and/or post-COVID-19 syndrome or the validation of current tools in these populations.

Conclusion

Many study participants with non-hospitalised COVID-19 pre-vaccination did not return to health and function up to one year later. GP screening for functional disability and compromised mental wellbeing up to one year after COVID-19 infection will facilitate targeted rehabilitation and timely psychosocial support.

Key points

- In unvaccinated Australians who have recovered from COVID-19 without requiring hospitalisation, severe fatigue is common seven months after acute illness.

- Fatigue can remain severe for up to one year.

- Where fatigue is severe, the patient is likely to have clinically significant anxiety and depression up to one year after infection.

- The ability to complete instrumental, occupational and social ADL can be impaired up to one year after infection.

- Respiratory symptoms and pain might not predominate 6–12 months after infection.